Spoiler Alert: The Universe Is Weird

How Do We Know What We Know?

January 20, 2026

Join iClicker

If you can’t scan: open the link and enter the course code ASES.

When you look up at the night sky,

what do you see?

What do you assume you’re seeing?

The Cosmic Treasure Chest

Most of Those Weren’t Stars

When you look up, you see stars, planets, maybe a galaxy or two…

But most of those points of light? Galaxies.

Each one containing hundreds of billions of stars.

You just saw millions of galaxies — and that’s only a tiny fraction of what one telescope will find.

How Do We Know That?

We’ve never been to another galaxy.

We’ve never touched a star.

We can’t send a probe to most of what we study.

So how do astronomers know anything about objects trillions of kilometers away?

(Later today: why astronomers switch to light-years (and parsecs) for cosmic distances.)

Today Is a Trailer

By the end of today, you’ll be able to…

- State the course thesis: pretty pictures → measurements → models → inferences

- Name the 4 things we can directly measure: brightness, position, wavelength, timing

- Explain why wavelength is the most powerful: it encodes temperature, composition, and motion

The Course Thesis

Pretty pictures → measurements →

models → inferences

What this means:

- Astronomical images aren’t just beautiful — they’re data

- We extract measurements from that data (how bright, what color, where, when)

- We apply physical models to interpret those measurements

- The result is an inference — a conclusion about something we can’t directly access

We Cannot Touch the Stars

Astronomy is the art of inferring physical reality from constrained measurements.

Constraint: We can only study the light that reaches us.

- No thermometers in the Sun

- No tape measures to galaxies

- No scales to weigh

Everything we claim to know is inferred from light.

NASA’s Three Big Questions

Think: Which question are you most curious about?

What Can We Actually Measure?

From billions of kilometers away, we can directly measure only four things.

The Four Observables

Direct observables (what we measure):

- Brightness — how much energy arrives per second

- Position — where on the sky, and how it moves

- Wavelength — what colors/spectrum are present

- Timing — how brightness or position changes over time

Quick Check: Direct Measurement

Which of these can astronomers directly measure for a distant star?

The Spoiler Reel

For each image, don’t memorize details — identify the pattern.

What do we measure?

(Which of the 4 observables?)

What do we infer?

(What physical claim do we make?)

Same pattern every time:

Observable → Model → Physical Reality

Spoiler 1: Nebulae — Colors Are Chemistry

![Annotated nebula image showing three labeled features: (1) Hydrogen-Alpha at 656.3 nm in red regions indicating ionized gas, (2) Doubly-ionized Oxygen [OIII] at 500 nm in blue-green regions indicating extremely low density, (3) Dark Lanes showing silhouettes of interstellar dust blocking the light.](../../../assets/images/module-01/forensic-analysis-of-a-nebula-nblm.png)

We measure: Colors at specific wavelengths

We infer: Chemical composition and dust structure

The physics: Each element emits/absorbs at unique wavelengths — a “spectral fingerprint”

Red = hydrogen (656 nm) Blue-green = oxygen (500 nm) Dark lanes = dust blocking light

Quick Check: Why Specific Colors?

Why do nebulae glow at specific colors instead of a continuous rainbow?

Spoiler 2: Spectroscopy — The Master Key

We measure: Brightness at each wavelength (a spectrum)

We infer: Temperature, composition, and motion

The physics: Atoms have quantized energy levels — electrons can only jump between specific rungs

Why it’s the master key:

A single brightness measurement = 1 data point. A spectrum = thousands of data points.

The Quantum Barcode

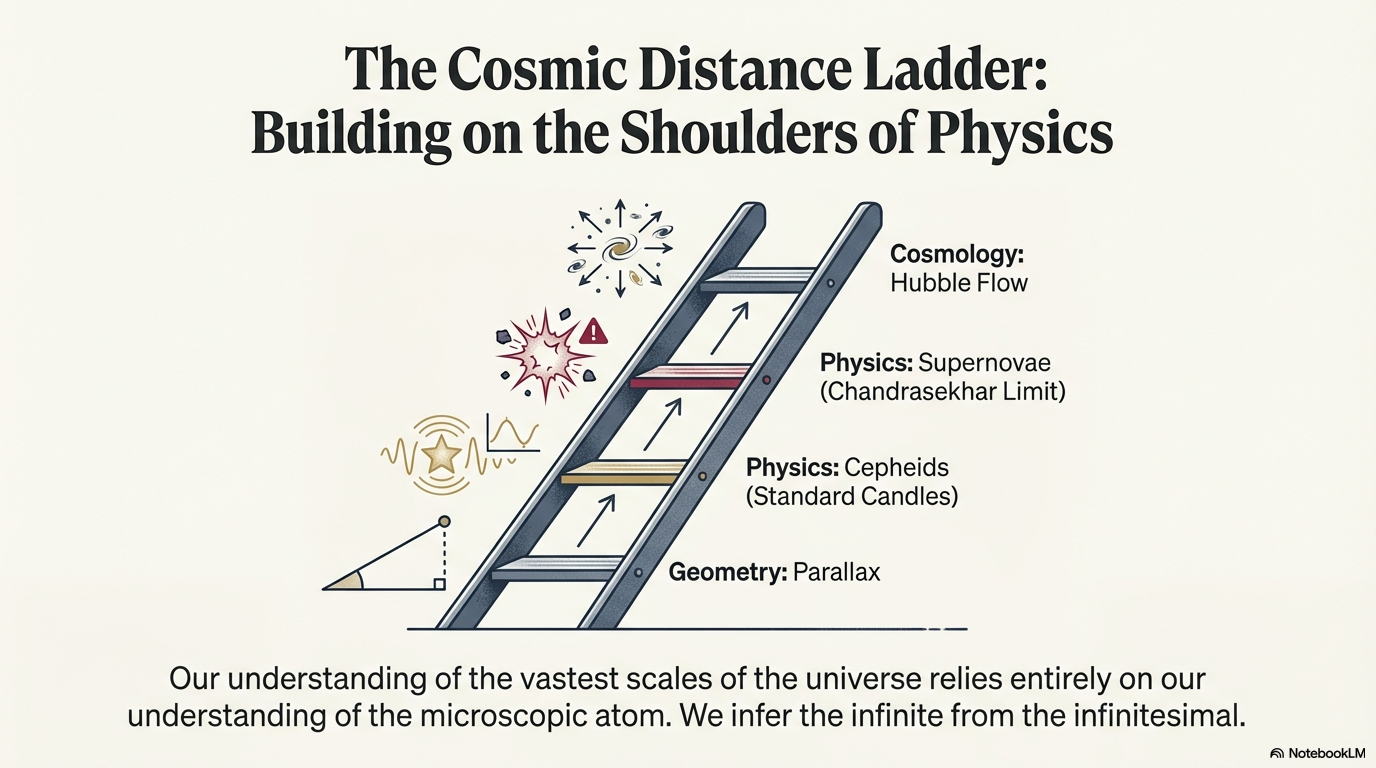

Spoiler 3: The Cosmic Distance Ladder

We measure: How bright an object appears (flux)

We infer: How far away it is

The physics: Light spreads out as it travels

— if you know the true brightness, you can calculate distance

A dim nearby source can look identical to a bright distant one

— physics breaks the tie.

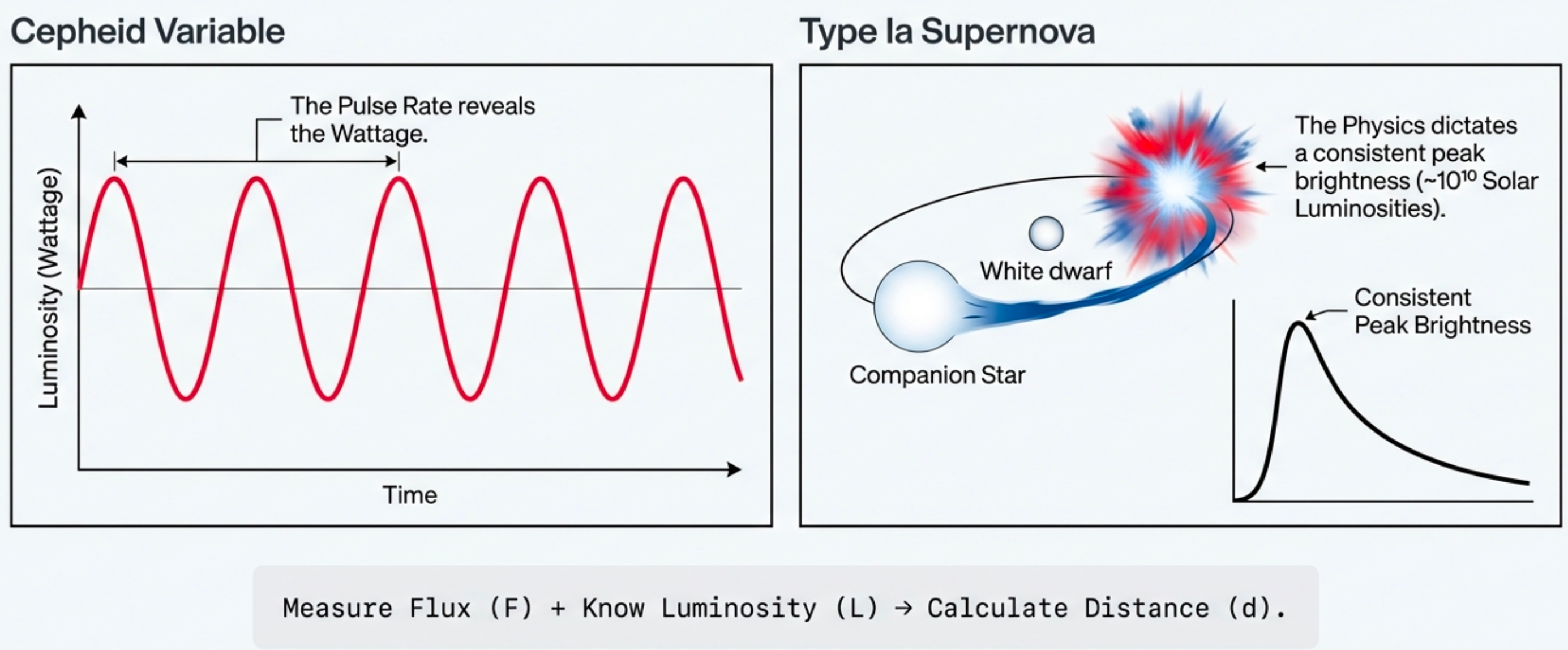

Standard Candles: Know the Brightness, Calculate the Distance

- Pulsating stars (period → luminosity)

- Exploding white dwarfs

(same mass → same brightness)

The key idea: If you know how bright something actually is (luminosity), and you measure how bright it appears (flux), you can calculate distance.

Standard candles: Objects whose true brightness we can predict from physics.

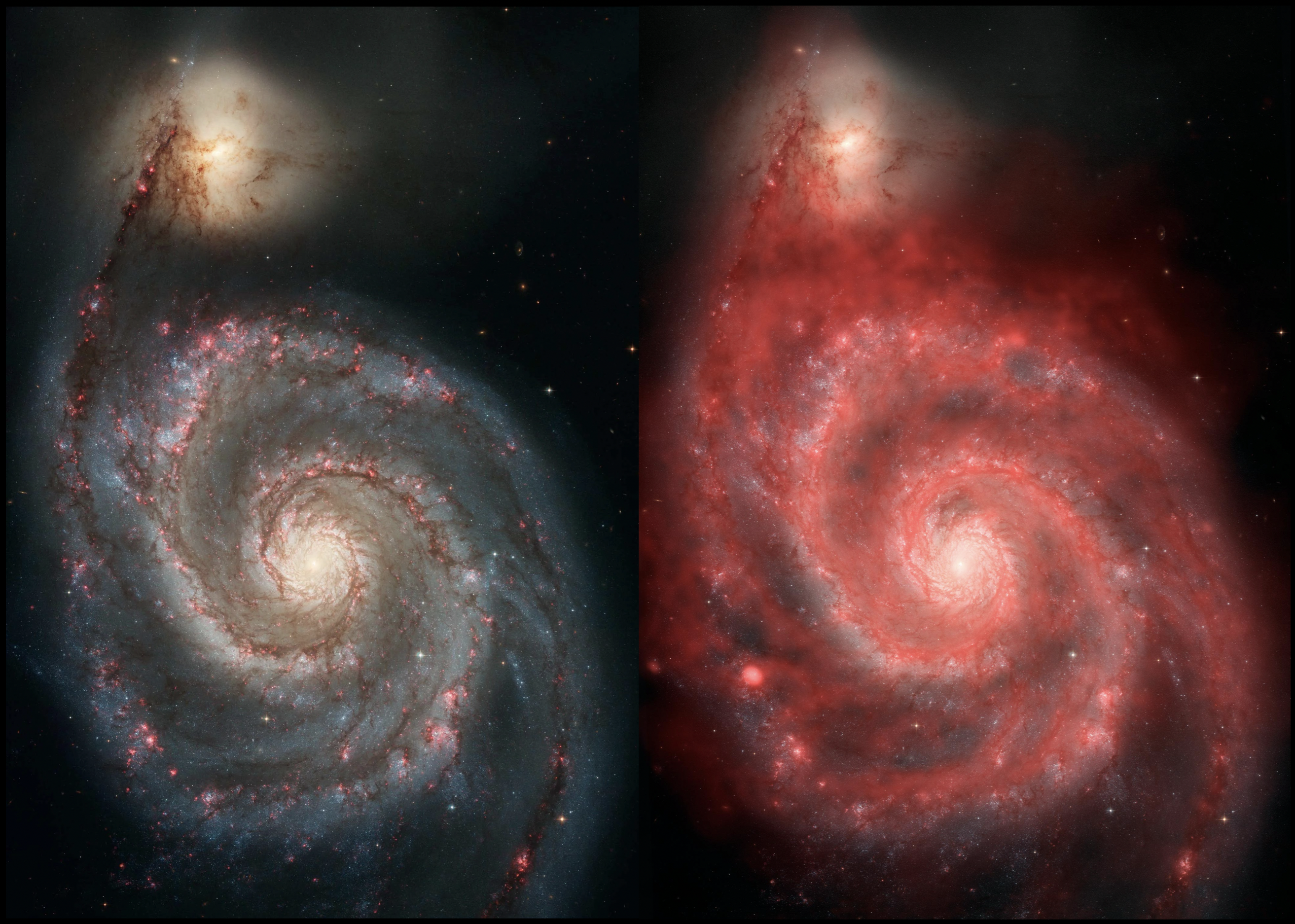

Spoiler 4: Same Galaxy, Different Physics

We measure: The same galaxy at different wavelengths

We infer: Different physical components are visible at different wavelengths

The physics: Different emission processes dominate at different wavelengths

Left (optical): Stars and dust lanes

Right (radio): Cold hydrogen gas

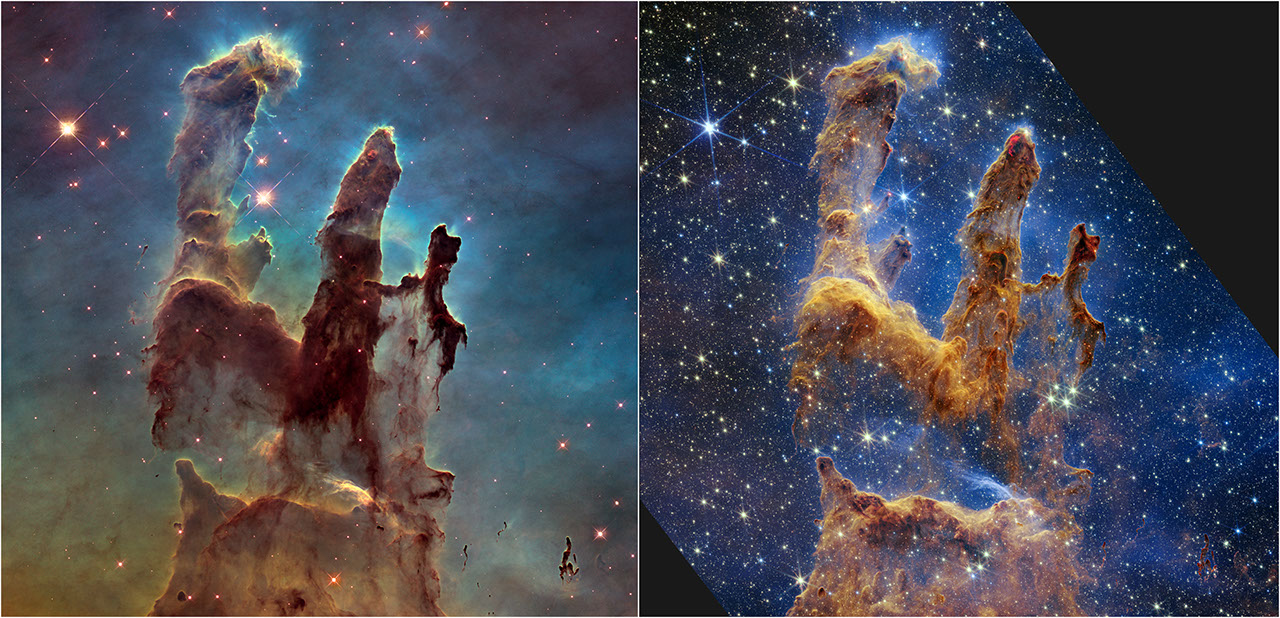

Spoiler 5: Infrared Reveals Hidden Stars

We measure: Optical vs infrared light from the same region

We infer: Newborn stars can hide inside dusty clouds

The physics: Dust blocks/scatters short wavelengths more than long wavelengths

Left (Hubble): Dark, opaque pillars

Right (JWST): Thousands of hidden newborn stars revealed

Spoiler 6: Hidden Mass — The Dark Matter Problem

We measure: how galaxies and stars move (from spectra over time)

We infer: extra unseen mass (“dark matter”)

The physics: gravity links motion to mass; if objects move too fast, there must be more mass than we can see

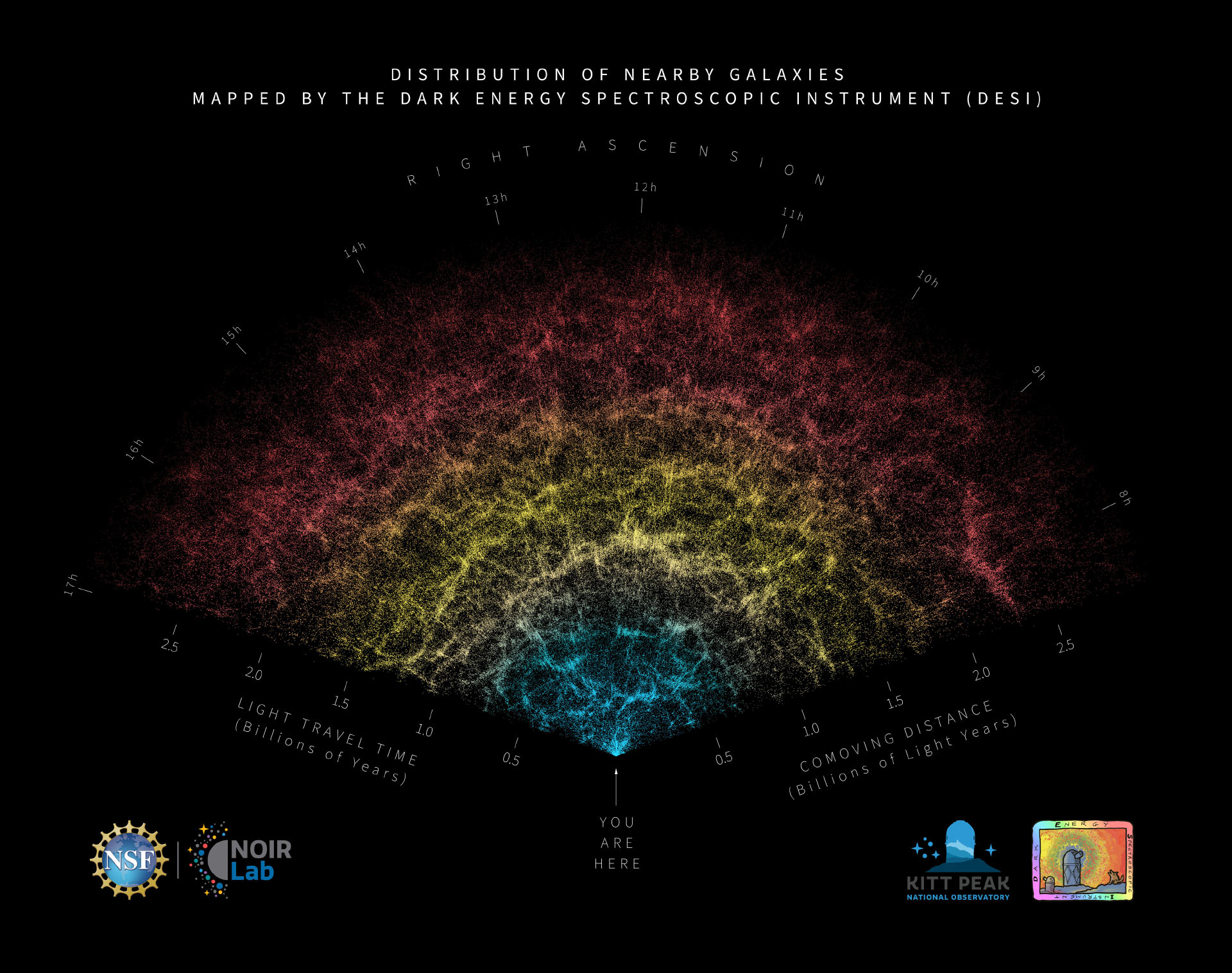

Spoiler 7: The Cosmic Web — Mapping the Universe in 3D

We measure: spectra (wavelength shifts) → redshifts → distances → 3D positions

We infer: the cosmic web (filaments + voids) and expansion-history constraints

The physics: gravity + cosmic expansion shape large-scale structure; mapping it tests cosmological models

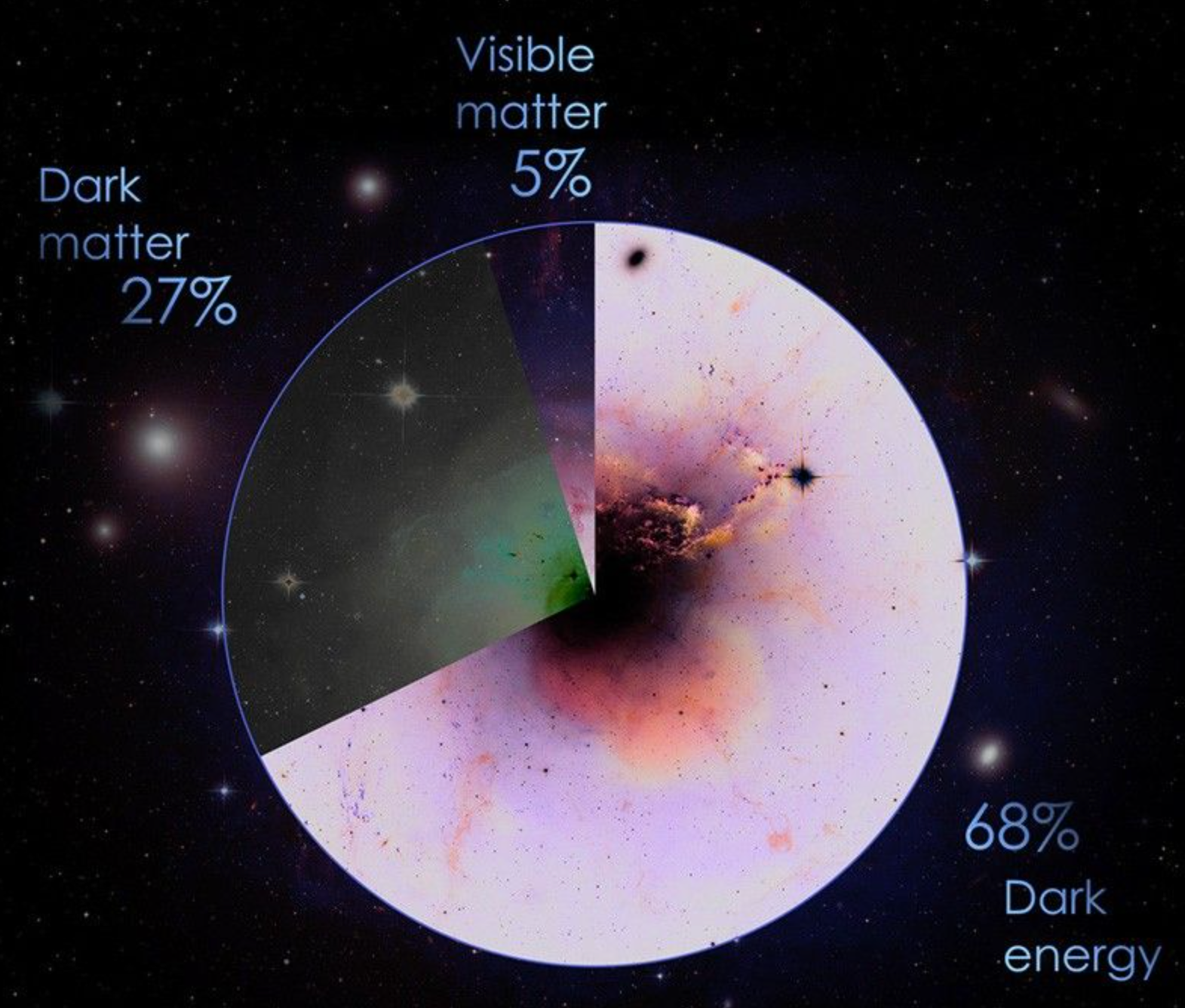

Spoiler 8: The Universe Is “Dark”

Dark Matter + Dark Energy

We measure: how the expansion rate changes with time (distance + redshift)

We infer: the expansion is accelerating → “dark energy”

The physics: gravity + cosmic expansion link energy content to expansion.

Acceleration implies a component that acts like “repulsive gravity”

Big question: How does dark energy evolve?

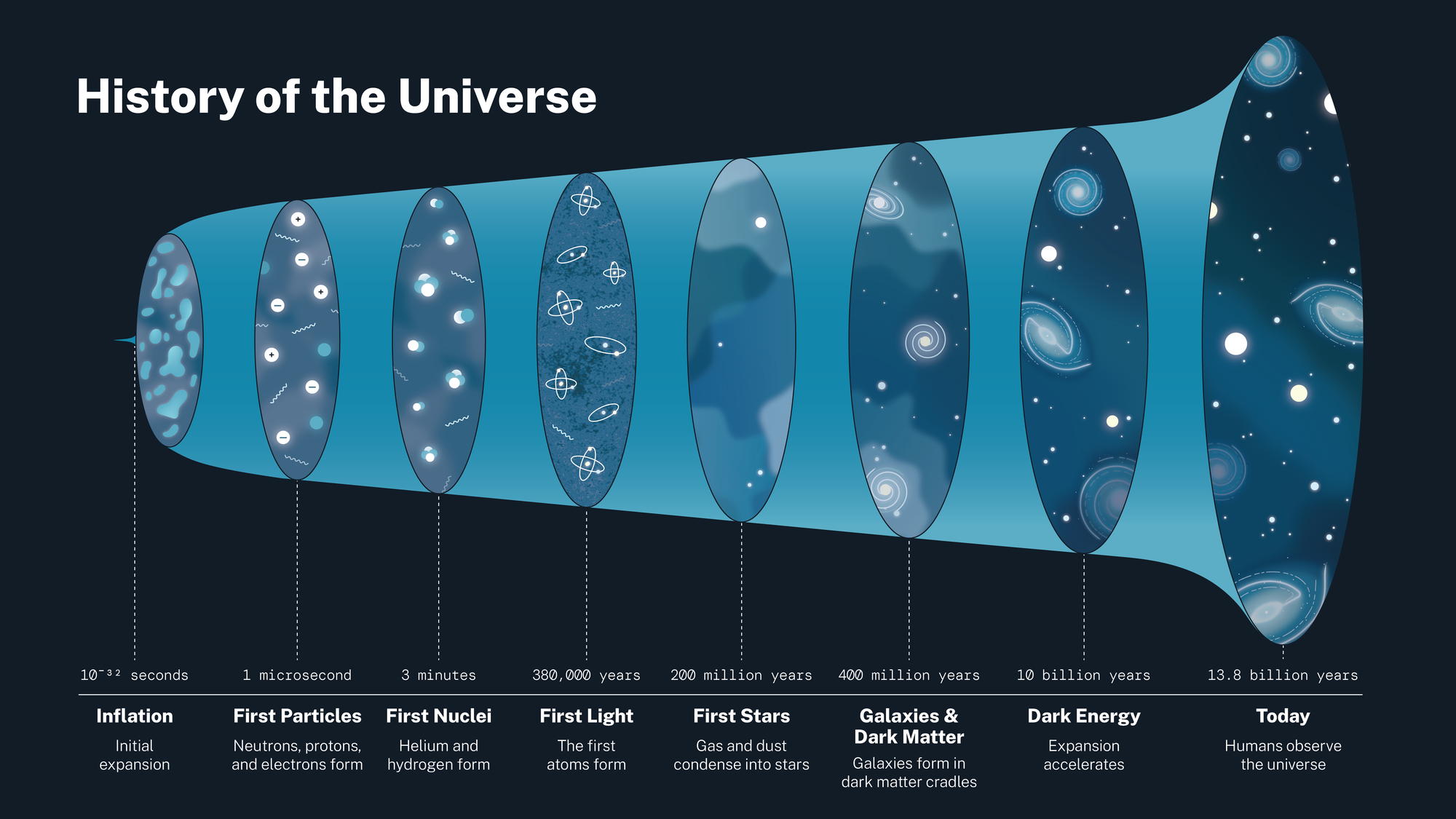

History of the Universe

Spoiler Synthesis: The Pattern Repeats

Every spoiler followed the same structure:

Observable → Model → Physical Reality

Which observable appeared most often?

(Hint: it starts with “W”)

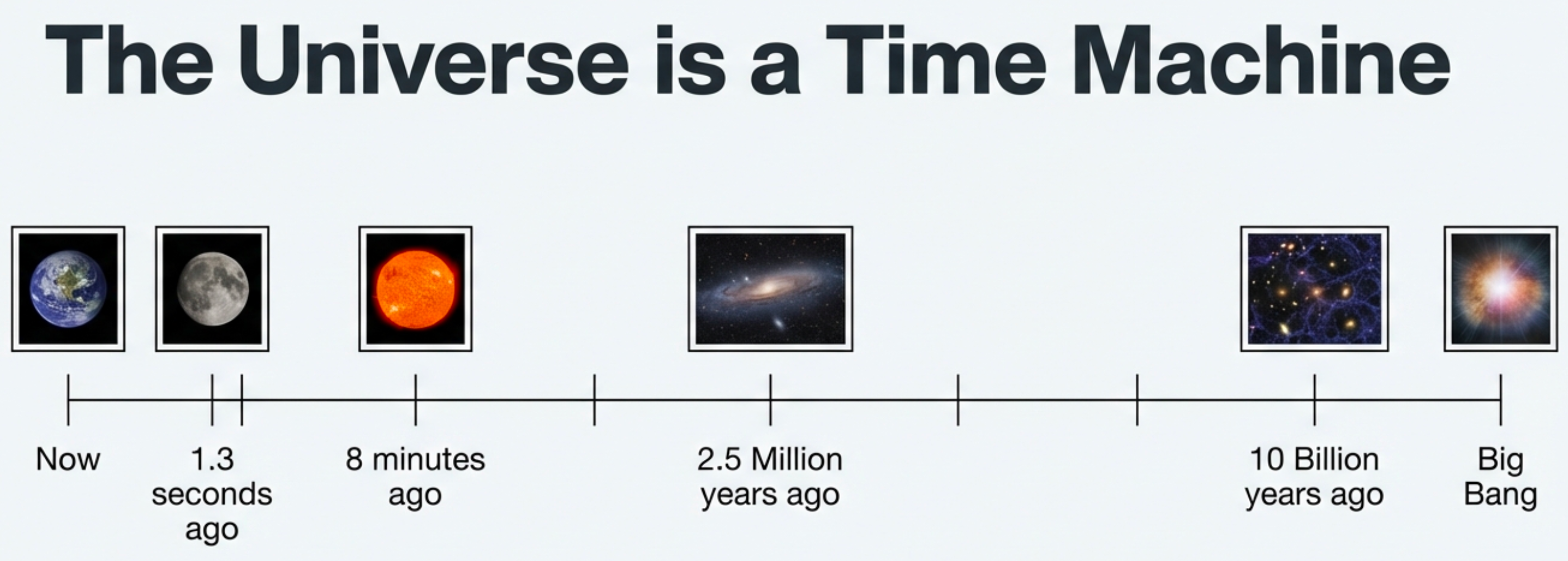

Lookback Time: Distance Is a Time Machine

| Object | You see it as it was… |

|---|---|

| The Moon | 1.3 seconds ago |

| The Sun | 8 minutes ago |

| Andromeda Galaxy | 2.5 million years ago |

| Distant galaxies | Billions of years ago |

Looking far away means looking into the past.

What’s a Light-Year?

A light-year is a unit of distance, not time.

Definition: The distance light travels in one year.

When we say a galaxy is “100 million light-years away,” we mean its light traveled for 100 million years to reach us.

How big is a light-year?

- Light speed: 300,000 km/s (3 × 10⁵ km/s)

- One year: ~31.5 million seconds (3.15 × 10⁷ s)

- 1 light-year ≈ 9.5 trillion km (9.5 × 10¹² km)

Quick Check: Lookback Time

You observe a galaxy 100 million light-years away.

When did the light you’re seeing leave that galaxy?

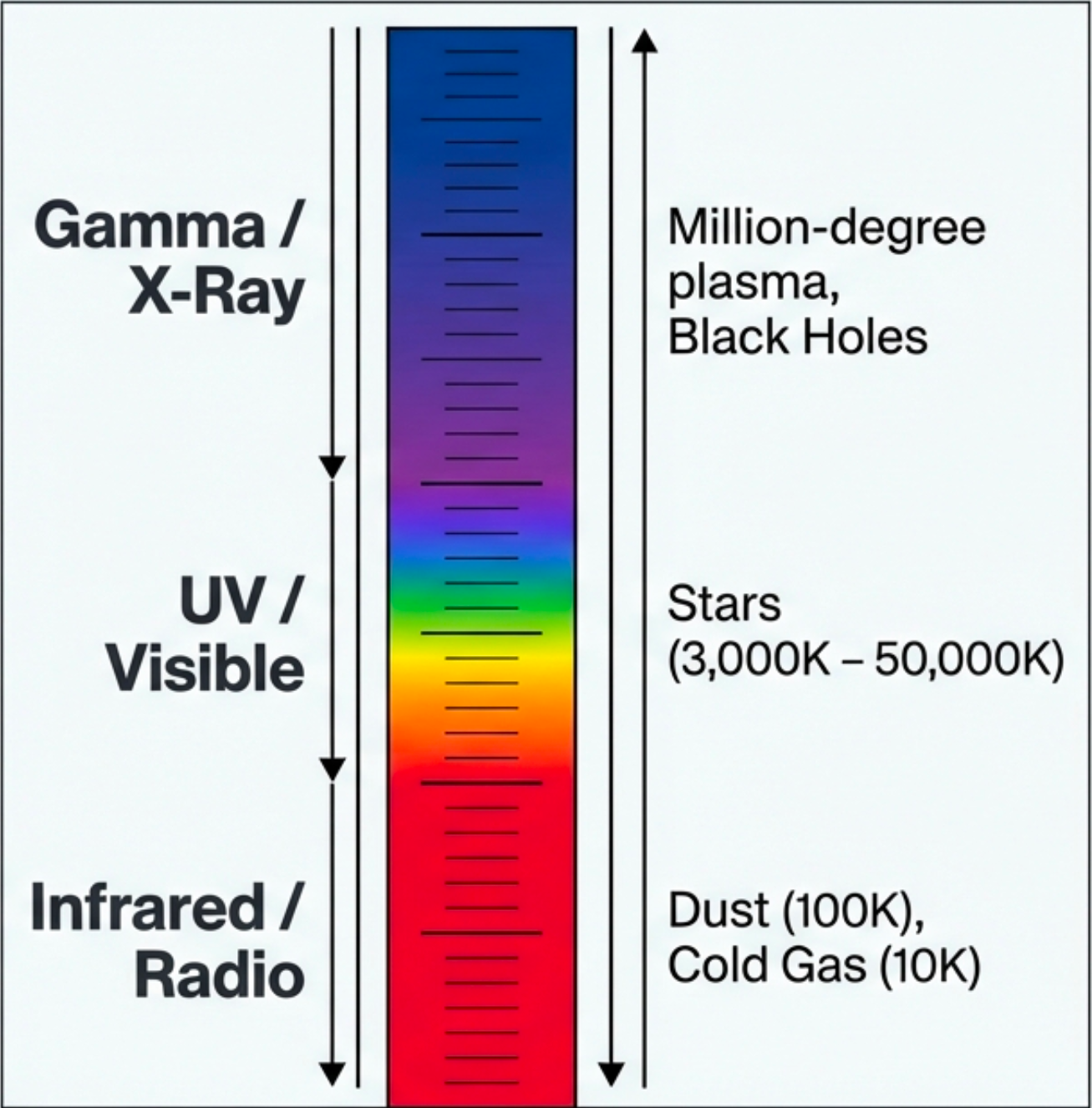

Wavelength Is Energy

The key relationship:

For thermal light: shorter wavelength = higher photon energy = hotter source

- Gamma/X-ray: Million-degree plasma, black holes

- Visible: Stellar surfaces (3,000–50,000 K)

- Infrared/Radio: Dust and cold gas (10–100 K)

This is why different telescopes see different physics — not just “better pictures.”

What You Can Recognize Now

After today, you should recognize these ideas when they return:

- The course thesis: Pretty pictures → measurements → models → inferences

- The four observables: Brightness, position, wavelength, timing

- The spoiler pattern: Observable → Model → Physical Reality

- Lookback time: Looking far away = looking into the past

- Wavelength: Encodes temperature, composition, and motion

Recognition, Not Retention

You are not expected to remember details yet.

Today was a trailer — a preview of coming attractions.

When these ideas return, you’ll recognize them. That’s the goal.

Questions We’ll Answer This Semester

- How do we know the Sun’s temperature if we can’t touch it?

- How do we weigh a star?

- How do we know the universe is 13.8 billion years old?

- What IS dark matter?

- How do we search for life on other planets?

Write down YOUR question. We’ll return to it.

Next Time: Math Boot Camp

Thursday: The Math We Need

- Scientific notation (writing very big and very small numbers)

- Powers of 10 and orders of magnitude

- Ratio reasoning (“if X doubles, what happens to Y?”)

- Dimensional analysis (do the units make sense?)

The math is not the obstacle — it’s the microscope.

Questions?

ASTR 101 • Lecture 1 • Dr. Anna Rosen