Lecture 2: Tools of the Trade

Math + Cosmic Scales Survival Kit

January 23, 2026

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture, you will be able to:

- Read and calculate with scientific notation (powers of ten)

- Use SI prefixes (kilo-, mega-, micro-, …) to translate scale

- Set up unit conversions so units cancel (factor-label method)

- Use the ratio method to compare planets/stars without big-number pain

- Solve simple rate problems (distance = speed × time; amount = rate × time)

- Use the astronomy “distance ladder” units: AU, light-year, parsec

A Word Before We Begin

Don’t panic about the equations!

Today I’ll show you examples using formulas we haven’t covered yet. You’re not expected to understand them fully — we’ll learn each one properly when its topic comes up.

For now, focus on the method, not the formula.

Think of it like watching a cooking demo before you have all the ingredients. You’re learning the technique — the details come later.

If the Sun were a cantaloupe in San Francisco…

…Earth would be a pinhead 15 meters away.

The nearest star? Another cantaloupe in Hawaii.

Why we’re doing this

Math as a telescope 🔭

In ASTR 101, numbers aren’t decoration — they’re how we turn points of light into physical reality.

- Units keep your equations honest.

- Ratios cancel constants and reveal relationships.

- Rates connect motion, time, and change.

- Powers of ten let your brain hold the cosmos.

Today’s Toolkit

Four survival tools 🧰

- Scientific notation + prefixes → speak “cosmic scale”

- Units + conversions → translate cleanly

- Ratio method → compare without drowning in zeros

- Rate problems → connect distance, time, and speed

Cosmic Scales in One Slide

A few anchor distances (order-of-magnitude is enough today):

| Scale | Distance | Light travel time |

|---|---|---|

| Earth–Moon | \(3.84\times10^8\,\text{m}\) | \(\sim 1.3\,\text{s}\) |

| 1 AU (Earth–Sun) | \(1.50\times10^{11}\,\text{m}\) | \(\sim 8.3\,\text{min}\) |

| 1 light-year (ly) | \(9.46\times10^{15}\,\text{m}\) | 1 year |

| 1 parsec (pc) | \(3.09\times10^{16}\,\text{m}\) | \(\sim 3.26\,\text{yr}\) |

The key idea

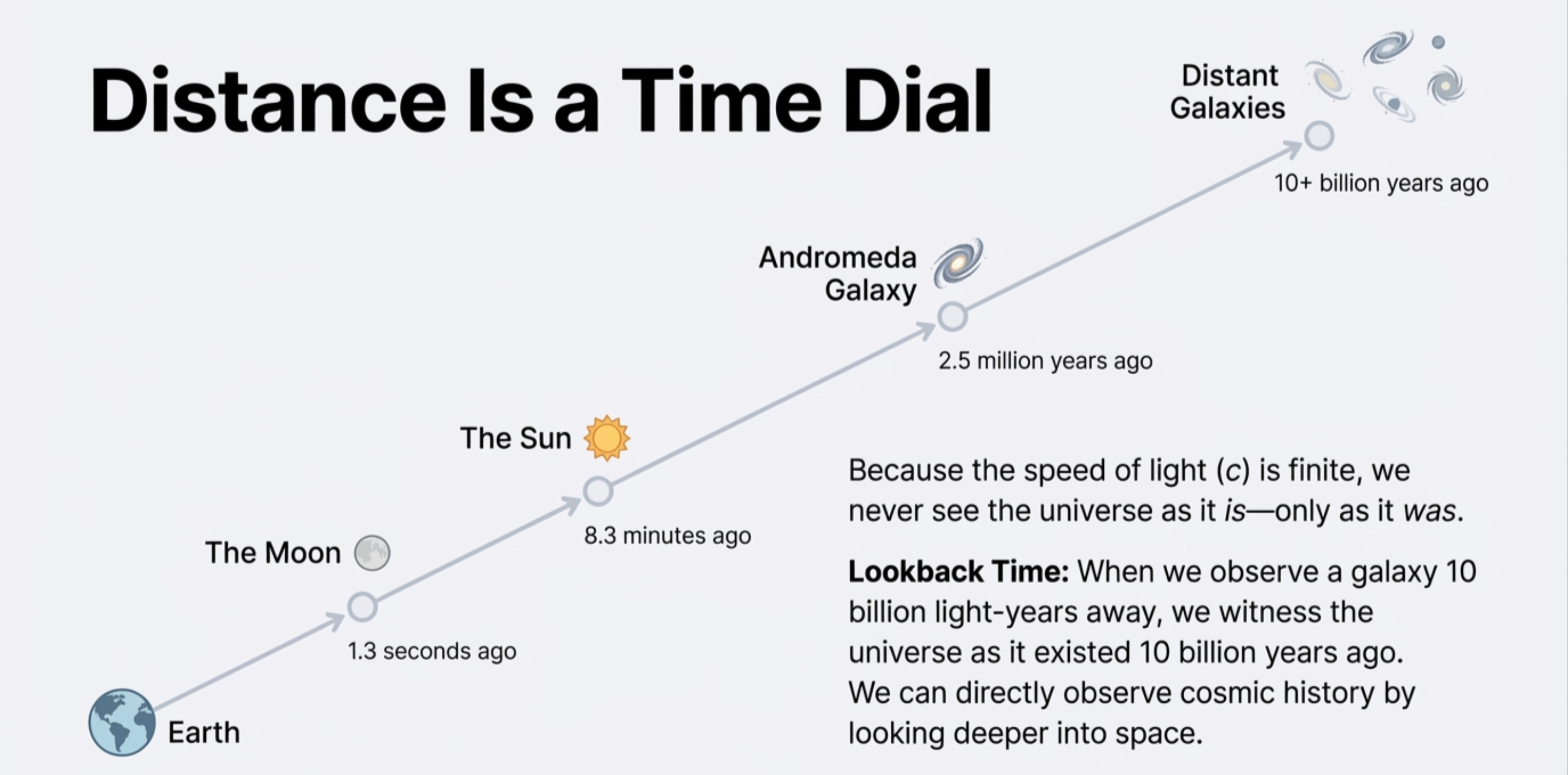

Distance and time mix in astronomy because information travels at a finite speed.

We don’t see things as they are. We see them as they were.

Common trap

A light-year is a distance, not a time — even though “year” is in the name. It’s how far light travels in one year: about 9.5 trillion km.

The Speed of Light: Nature’s Speed Limit

Light is the fastest thing in the universe. Nothing can travel faster.

\[c = 300{,}000\,\text{km/s} = 3 \times 10^8\,\text{m/s}\]

- Light travels 1 meter in about 3 nanoseconds

- Light crosses Earth’s diameter in 0.04 seconds

- Light reaches the Moon in 1.3 seconds

- Light reaches the Sun in 8.3 minutes

Every galaxy in this image is a time capsule. The light we see left millions to billions of years ago — we’re seeing them as they were, not as they are.

What a Light-Year Really Means

A light-year is a distance, not a time — even though “year” is in the name.

It’s how far light travels in one year:

\[1\,\text{ly} \approx 9.5 \times 10^{15}\,\text{m}\]

That’s about 9.5 trillion kilometers.

Why use light-years?

“Proxima Centauri is \(4 \times 10^{16}\) m away” is painful.

“4.2 light-years” is memorable.

Distance Is a Time Machine

Because light takes time to travel, looking far away = looking back in time.

| Object | Distance | You see it as it was… |

|---|---|---|

| Moon | 1.3 light-sec | 1.3 seconds ago |

| Sun | 8.3 light-min | 8.3 minutes ago |

| Proxima Centauri | 4.2 ly | 4.2 years ago |

| Andromeda Galaxy | 2.5 Mly | 2.5 million years ago |

Mind-bending implication

The further we look, the further back in time we see.

The most distant galaxies show us the universe as it was billions of years ago.

Why We Need These Tools

These cosmic scales are why we need a math survival kit:

- Scientific notation — to write \(9{,}500{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000\) m as \(9.5 \times 10^{15}\) m

- Unit conversions — to translate between meters, km, AU, and light-years

- Ratios — to compare without drowning in zeros

- Rate problems — to connect distance, speed, and time

These aren’t abstract math exercises. They’re the tools that let us decode the universe.

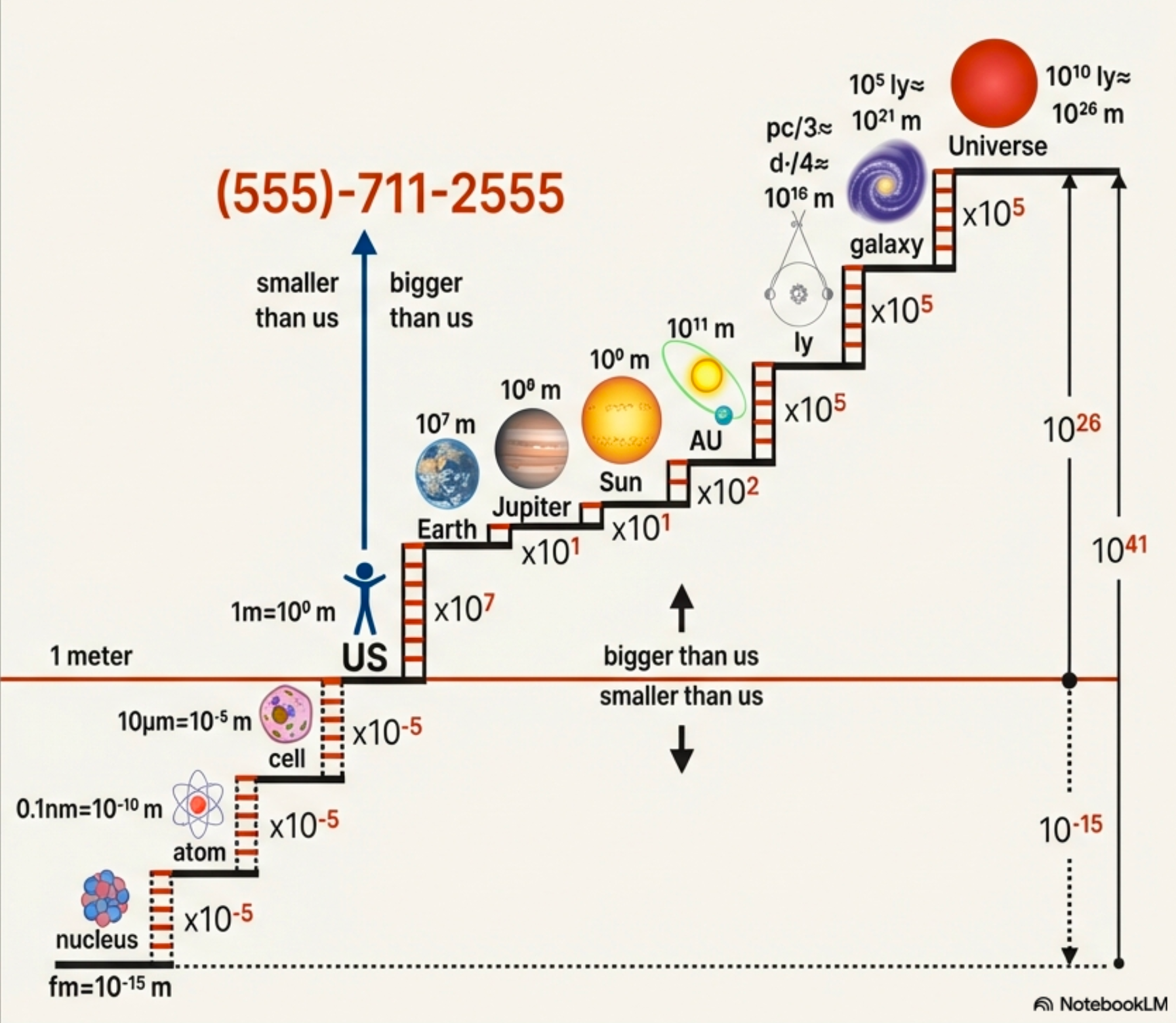

The Universe’s Phone Number

Each step on this ladder is a factor of 10.

From your desk to the edge of the observable universe takes about 27 steps.

The mnemonic

(555)-711-2555 encodes the multipliers at each scale jump. Astronomers really do use phone-number tricks to navigate cosmic scales!

Stop & Solve 0: Light-time intuition

Light takes about 8.3 minutes to travel 1 AU.

- How long does it take light to reach us from something at 2 AU?

- How long from 0.5 AU?

Tool 1: Scientific Notation

Because the universe refuses to be written out in longhand

Scientific notation = brain-friendly compression

A number written as

\[a\times 10^n\]

means:

- \(a\) is the coefficient (usually between 1 and 10)

- \(10^n\) tells you how many places the decimal moves

- \(n\) is the order of magnitude (the scale)

Converting: decimal ↔︎ scientific notation

Big number

\(300{,}000{,}000\,\text{m/s} = 3.0\times10^8\,\text{m/s}\)

Small number

\(0.000000001\,\text{s} = 1.0\times10^{-9}\,\text{s}\)

Direction rule

- \(n>0\) → move decimal right (bigger)

- \(n<0\) → move decimal left (smaller)

Operations (no calculator vibe)

- Multiply: \((a\times10^m)(b\times10^n)=(ab)\times10^{m+n}\)

- Multiply the coefficients, add the exponents

- Divide: \(\dfrac{a\times10^m}{b\times10^n}=\left(\dfrac{a}{b}\right)\times10^{m-n}\)

- Divide the coefficients, subtract the exponents

- Powers: \((a\times10^m)^k = a^k\times10^{mk}\)

- Raise the coefficient to the power, multiply the exponent

Why this works

Exponents are a shorthand for repeated multiplication. Adding exponents = multiplying powers of ten: \(10^3 \times 10^2 = 10^{3+2} = 10^5\).

Quick Check: Scientific Notation

What is \((3 \times 10^5)(4 \times 10^3)\)?

SI Prefixes: the language of scale

| Prefix | Symbol | Factor |

|---|---|---|

| tera | T | \(10^{12}\) |

| giga | G | \(10^{9}\) |

| mega | M | \(10^{6}\) |

| kilo | k | \(10^{3}\) |

| milli | m | \(10^{-3}\) |

| micro | \(\mu\) | \(10^{-6}\) |

| nano | n | \(10^{-9}\) |

Order-of-magnitude estimation (OoM)

When exact arithmetic is annoying, estimate on purpose.

- Round coefficients to nearby easy numbers.

- For a rough order-of-magnitude:

- coefficient \(< 3\) → round to 1

- coefficient \(> 3\) → round to 10

OoM is not “sloppy.” It’s a controlled approximation for staying in the right cosmic zip code.

Tool 2: Units & Conversions

Units are the meaning of a number

What’s a Physical Quantity?

A physical quantity = a number + a unit

✓ Physical quantities

- 3 meters

- 5.9 × 10²⁴ kg

- 300,000 km/s

✗ Not physical quantities

- “3” (three what?)

- “really far”

- “super hot”

The unit is not optional. Without it, the number is meaningless.

What’s a Physical Constant?

A physical constant is a number that nature gives us — it doesn’t change.

- Speed of light: \(c = 3 \times 10^8\) m/s — the universe’s speed limit

- Gravitational constant: \(G = 6.67 \times 10^{-11}\) m³/(kg·s²) — how strong gravity is

- Planck’s constant: \(h = 6.63 \times 10^{-34}\) J·s — the “graininess” of energy

Why do constants matter?

They’re conversion factors between different physical quantities. The speed of light \(c\) converts between distance and time. That’s why light-years work!

Units vs. Dimensions (very light intro)

Units are human choices:

- meters vs kilometers vs AU

Dimensions are the type of quantity:

- length \([L]\), time \([T]\), mass \([M]\)

Examples:

- speed: \([L/T]\)

- area: \([L^2]\)

- volume: \([L^3]\)

![Split diagram contrasting UNITS (The Map) showing ruler, stopwatch, and weights labeled as 'human inventions, fungible, arbitrary' versus DIMENSIONS (The Territory) showing [L], [T], [M] symbols labeled as 'physical realities, invariant, fundamental'. Footer states physical laws must hold regardless of units used.](../../../assets/images/module-01/units-vs-dimensions-nblm.png)

Why mention dimensions?

Not to do a full “dimension analysis” unit…but because unit mistakes are the #1 avoidable error in astronomy problems.

Conversion factors = “multiply by 1”

A conversion factor is an equality written as a fraction.

Example:

\[1\,\text{m} \leftrightarrow 100\,\text{cm}\]

so you can use

\[\frac{100\,\text{cm}}{1\,\text{m}}=1 \quad \text{or} \quad \frac{1\,\text{m}}{100\,\text{cm}}=1.\]

The factor-label method (foolproof)

Write what you’re given.

Multiply by conversion factors arranged so units cancel.

Check that your final units match what you wanted.

Selection rule

Put the unit you want to remove in the denominator.

Example: minutes → hours (structure, not memorization)

\[1000\,\text{min}\times\frac{1\,\text{hr}}{60\,\text{min}} = \frac{1000}{60}\,\text{hr}\approx 16.7\,\text{hr}\]

Sanity check: hours are bigger units than minutes, so the number should get smaller. ✓

Stop & Solve 2: Unit conversion chains

A) Convert \(60\,\text{mph}\) to \(\text{m/s}\).

B) Convert \(0.5^\circ\) to arcseconds.

(Use: \(1\,\text{mile}=1.6\,\text{km}\), \(1\,\text{hr}=3600\,\text{s}\), \(1^\circ=60\,\text{arcmin}\), \(1\,\text{arcmin}=60\,\text{arcsec}\).)

Quick vocab: angular units

Astronomers measure tiny angles in arcminutes (1/60 of a degree) and arcseconds (1/60 of an arcminute). The Moon is about 30 arcmin wide; a star’s disk is less than 0.05 arcsec.

Exponents matter in unit conversions

When a unit is squared or cubed, the conversion factor gets squared/cubed too.

The trap: Students often write

\[1\,\text{m}^3 = 100\,\text{cm}^3\] ❌

Why it’s wrong: You’re converting each dimension.

The right way:

\[1\,\text{m} = 100\,\text{cm}\]

\[1\,\text{m}^3 = (1\,\text{m})^3 = (100\,\text{cm})^3\]

\[= 100^3\,\text{cm}^3 = 10^6\,\text{cm}^3\] ✓

Rule: When converting \(\text{m}^n\), raise the conversion factor to the \(n\)th power too.

Pro tip: Parentheses are your best friend — wrap the number and unit together: \((100\,\text{cm})^3\), not \(100\,\text{cm}^3\).

Compound Units: Building Blocks

Physics has only three base dimensions: length \([L]\), mass \([M]\), time \([T]\).

Everything else is built from combinations:

- Velocity = distance / time → \([L]/[T]\)

- Acceleration = velocity / time → \([L]/[T^2]\)

- Force = mass × acceleration → \([M][L]/[T^2]\)

The building principle

Complex quantities are just base dimensions multiplied and divided. If you know the recipe, you can always check your work.

Reference: Common Physical Quantities

| Quantity | Dimension | SI Unit | Named Unit |

|---|---|---|---|

| Length | \([L]\) | m | meter |

| Mass | \([M]\) | kg | kilogram |

| Time | \([T]\) | s | second |

| Velocity | \([L][T]^{-1}\) | m/s | — |

| Acceleration | \([L][T]^{-2}\) | m/s² | — |

| Force | \([M][L][T]^{-2}\) | kg·m/s² | Newton (N) |

| Energy | \([M][L]^2[T]^{-2}\) | kg·m²/s² | Joule (J) |

| Power | \([M][L]^2[T]^{-3}\) | kg·m²/s³ | Watt (W) |

| Pressure | \([M][L]^{-1}[T]^{-2}\) | kg/(m·s²) | Pascal (Pa) |

Named units are shortcuts. A Newton is just kg·m/s². A Joule is just kg·m²/s². If a unit looks unfamiliar, rewrite it in base units!

Tool 3: The Ratio Method

Compare systems without calculator misery

Absolute vs. ratio (why ratios are magic)

The hard way: Calculate Jupiter’s surface gravity.

- Need: \(G = 6.67 \times 10^{-11}\,\text{N}\cdot\text{m}^2/\text{kg}^2\), mass, radius…

- Lots of numbers, easy to make mistakes.

The ratio way: Compare Jupiter to Earth.

- Jupiter is 318× Earth’s mass, 11× Earth’s radius

- We know Earth’s gravity (9.8 m/s²)

The pattern

If \(A = k B^n\), then comparing two cases:

\[\frac{A_2}{A_1}=\left(\frac{B_2}{B_1}\right)^n\]

The constant \(k\) cancels!

What this says: Ratios let you compare systems using only the relationship between quantities — no need to look up constants.

Scaling patterns you’ll use all semester

| Scaling | Meaning | Where it shows up |

|---|---|---|

| \(\propto R^2\) | area grows fast | telescope area, surface area |

| \(\propto R^3\) | volume grows very fast | planet volumes, “how many Earths” |

| \(\propto 1/r^2\) | inverse-square | brightness, gravity |

Worked Example: Telescope Collecting Area

Problem: The Keck telescope has a 10-meter diameter mirror. The Hubble Space Telescope has a 2.4-meter diameter mirror. How much more light can Keck collect?

Setup: Light-collecting area scales as \(A \propto D^2\) (area of a circle)

Ratio method: \[\frac{A_\text{Keck}}{A_\text{Hubble}} = \left(\frac{D_\text{Keck}}{D_\text{Hubble}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{10}{2.4}\right)^2 \approx (4.2)^2 \approx 17\]

Answer: Keck collects about 17× more light than Hubble — no need to calculate actual areas!

Quick Check: Volume Ratio

The Sun’s radius is about 109× Earth’s radius. How many Earths fit inside the Sun?

Using \(V \propto R^3\), what is \(V_\odot / V_\oplus\)?

Applying the Pattern: Comparing Stars

What we measure: Brightness ratio of two stars (same apparent brightness)

What physics says: Inverse-square law means equal brightness at different distances implies different luminosities

What we conclude: A star 10× further away but equally bright must be 100× more luminous

The ratio shortcut

\(\frac{L_2}{L_1} = \left(\frac{d_2}{d_1}\right)^2 = 10^2 = 100\)

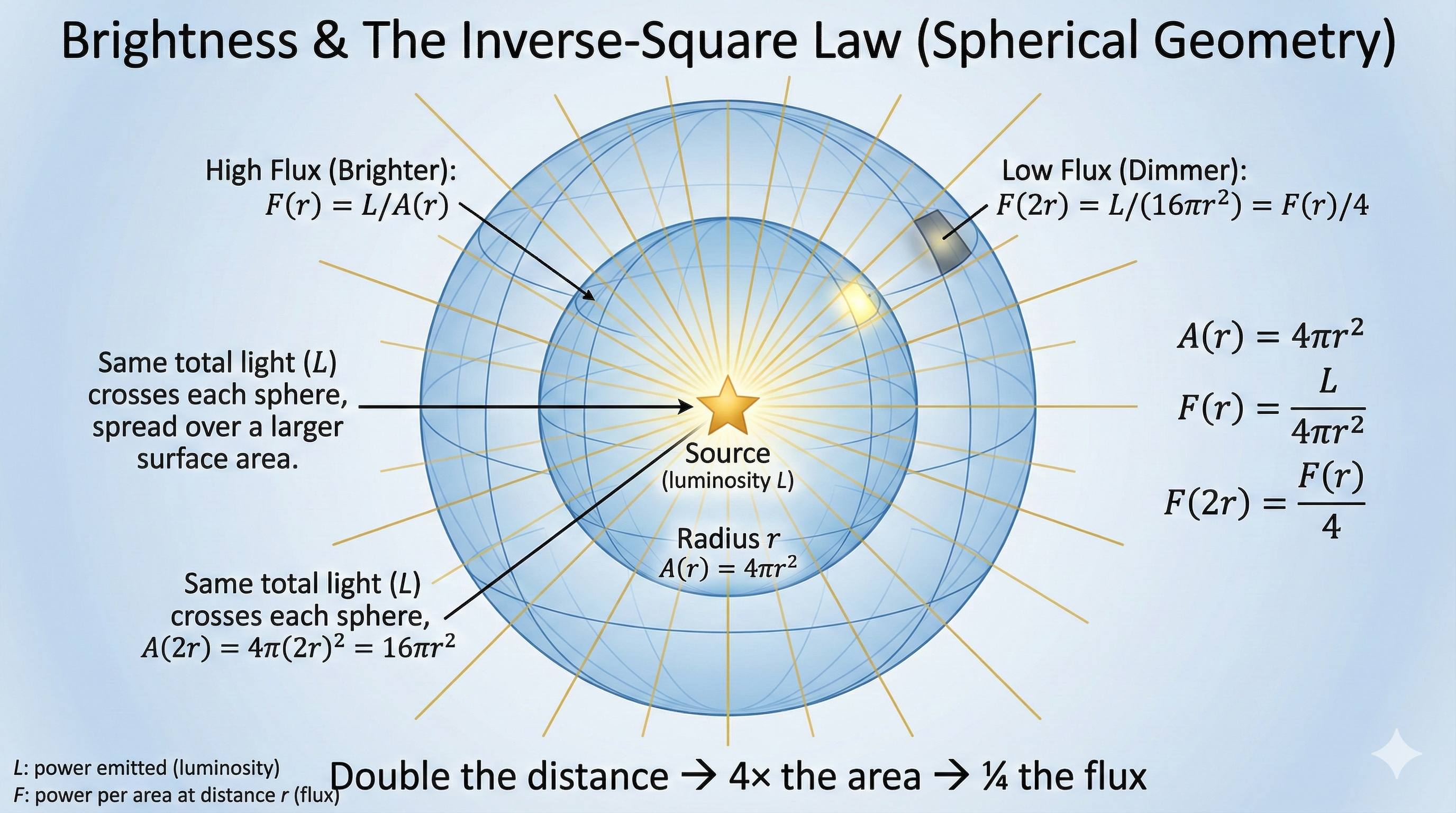

Inverse-square intuition (brightness)

If you move twice as far from a light source:

\[\text{brightness}\propto \frac{1}{d^2}\]

Watch the flip!

Because brightness is inversely proportional to \(d^2\), the ratio flips:

\[\frac{B_2}{B_1}=\left(\frac{d_1}{d_2}\right)^2\]

Astronomers call this flux — energy per second per area (W/m²).

Example: Twice as far → \(\dfrac{B_2}{B_1}=\left(\dfrac{1}{2}\right)^2=\dfrac{1}{4}\) the brightness.

Worked Example: Mars Sunlight

Problem: Mars orbits at 1.5 AU from the Sun. Earth orbits at 1 AU. How does the intensity of sunlight on Mars compare to Earth?

Setup: Sunlight intensity follows the inverse-square law: \(I \propto 1/d^2\)

Ratio method: \[\frac{I_\text{Mars}}{I_\text{Earth}} = \left(\frac{d_\text{Earth}}{d_\text{Mars}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{1}{1.5}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2 = \frac{4}{9} \approx 0.44\]

Answer: Mars receives only 44% as much sunlight as Earth — less than half!

This is why solar panels on Mars rovers need to be so large. (Mars is cold mostly because its thin atmosphere can’t trap heat — but less sunlight doesn’t help!)

Applying the Pattern: Distance from Brightness

What we measure: Brightness (flux \(F\)) — how much light arrives at our detector (W/m²)

What physics says: Inverse-square law relates flux, luminosity, and distance:

\[F = \frac{L}{4\pi d^2}\]

where \(L\) = luminosity (total power output, in Watts) and \(d\) = distance

What we conclude: If we know a star’s true luminosity \(L\) and measure its flux \(F\), we can solve for distance \(d\)

The inference chain

Observable (\(F\)) → Model (inverse-square) → Physical property (\(d\))

Tool 4: Rate Problems

Change per time is basically the universe’s favorite sentence structure

The rate template

Most rate problems are one equation with three rearrangements:

\[\text{amount} = \text{rate}\times\text{time}\]

- Find rate: \(\text{rate}=\dfrac{\text{amount}}{\text{time}}\)

- “How fast?”

- Find time: \(\text{time}=\dfrac{\text{amount}}{\text{rate}}\)

- “How long?”

- Find amount: \(\text{amount}=\text{rate}\times\text{time}\)

- “How much/far?”

Astronomy examples

- Distance = speed × time

- Energy = power × time

- Mass loss = rate × time

What this says: If you know any two of these, you can find the third. This single pattern solves most “how far/fast/long” questions.

Worked Example: Building a Light-Year

Problem: How far does light travel in one year? (In meters)

Step 1: Identify the rate equation

\[\text{distance} = \text{speed} \times \text{time}\]

Step 2: Gather your values

- Speed of light: \(c = 3 \times 10^8\,\text{m/s}\)

- Time: \(1\,\text{year}\)

But wait — the units don’t match! We need time in seconds.

Step 3: Convert 1 year → seconds

\[1\,\text{yr} \times \frac{365\,\text{days}}{1\,\text{yr}} \times \frac{24\,\text{hr}}{1\,\text{day}} \times \frac{3600\,\text{s}}{1\,\text{hr}}\]

\[= 365 \times 24 \times 3600\,\text{s}\]

\[\approx 3.15 \times 10^7\,\text{s}\]

Worked Example: Building a Light-Year (continued)

Step 4: Multiply using scientific notation

\[1\,\text{ly} = c \times t = (3 \times 10^8\,\text{m/s}) \times (3.15 \times 10^7\,\text{s})\]

Scientific notation multiplication rule

Multiply coefficients, add exponents: \((a \times 10^m) \times (b \times 10^n) = (a \times b) \times 10^{m+n}\)

\[= (3 \times 3.15) \times 10^{8+7}\,\text{m}\] \[= 9.45 \times 10^{15}\,\text{m}\]

Answer: \(1\,\text{ly} \approx 9.5 \times 10^{15}\,\text{m}\) (about 9.5 trillion kilometers)

Applying the Pattern: Lookback Time

What we measure: Distance to a galaxy (in light-years)

What physics says: Light travels at \(c = 3 \times 10^8\) m/s (finite speed)

What we conclude: A galaxy 2.5 million light-years away → we see it as it was 2.5 million years ago

Distance is a time machine. The further we look, the further back in time we see.

Distance Is a Time Dial

Stop & Solve 4: Earth’s orbital “speed”

Earth moves around the Sun at about \(29.8\,\text{km/s}\).

How far does Earth travel in one minute? (Answer in meters.)

Putting it together: a problem-solving checklist

The decoding ritual

For any quantitative astronomy question:

- What am I finding? (write target with units)

- What am I given? (write givens with units)

- Pick the tool: conversion, ratio, or rate

- Do the unit cancellation (this is your error detector)

- Sanity check: bigger unit → smaller number? right power of ten?

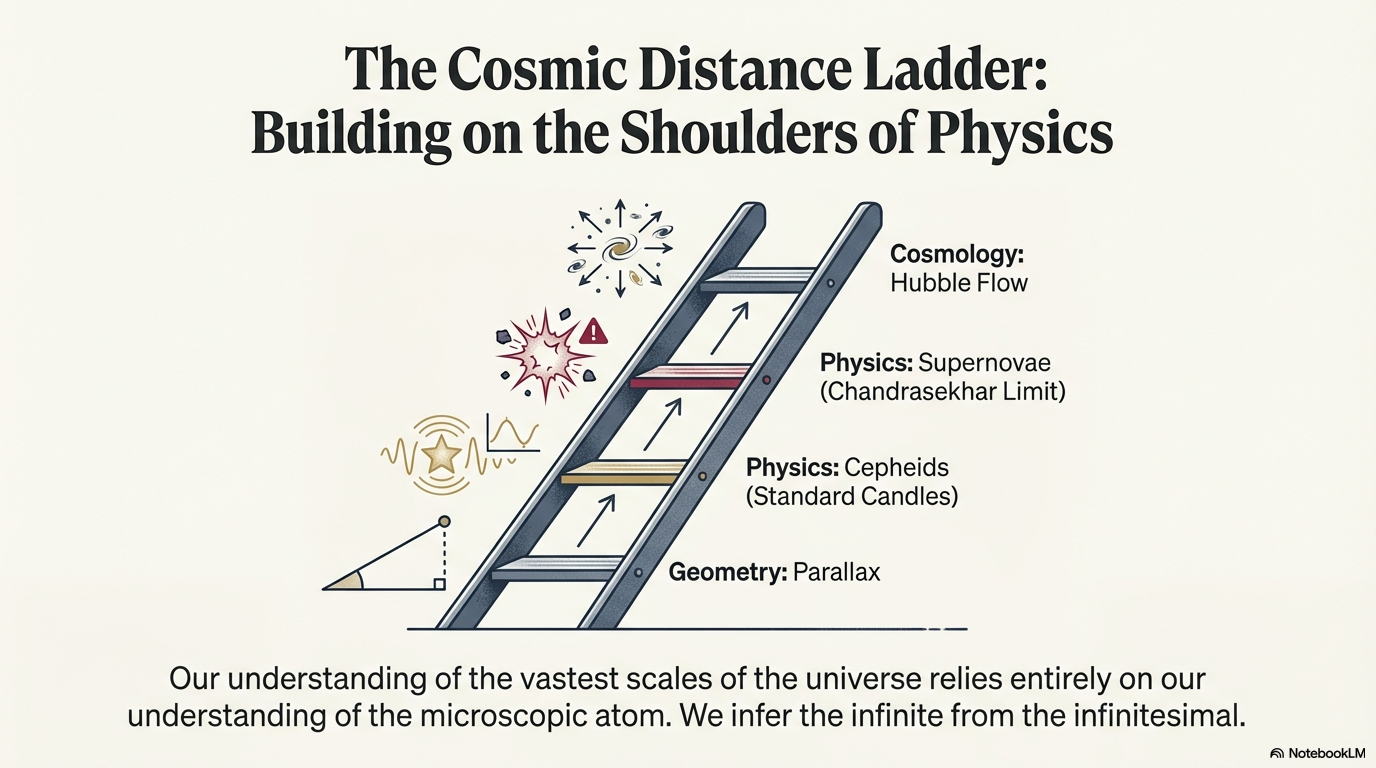

The Cosmic Distance Ladder

Quick Reference: Astronomy unit ladder

| Unit | What it’s good for | Useful fact |

|---|---|---|

| AU | solar system distances | \(1\,\text{AU}\approx 1.50\times10^{11}\,\text{m}\) |

| ly | “how far light goes” | \(1\,\text{ly}\approx 9.46\times10^{15}\,\text{m}\) |

| pc | star/galaxy distances | \(1\,\text{pc}\approx 3.09\times10^{16}\,\text{m}\approx 3.26\,\text{ly}\) |

What to Take Away

Recognition, not retention

You don’t need to memorize formulas. You need to recognize patterns:

- Powers of ten compress cosmic scales

- Ratios reveal relationships without constants

- Units keep your equations honest

- Rates connect distance, time, and speed

When you see a big number or a scaling question, you’ll know which tool to reach for.

Exit Ticket

If you move twice as far from a light source, brightness becomes…

Solutions

Solution 0

- \(2\,\text{AU}\): \(2\times 8.3\,\text{min}\approx 16.6\,\text{min}\)

- \(0.5\,\text{AU}\): \(0.5\times 8.3\,\text{min}\approx 4.15\,\text{min}\)

Solution 1

Step 1: Multiply the coefficients \[3 \times 4 = 12\]

Step 2: Add the exponents \[10^5 \times 10^3 = 10^{5+3} = 10^8\]

Step 3: Combine \[12 \times 10^8\]

Step 4: Normalize (coefficient should be between 1 and 10) \[12 \times 10^8 = 1.2 \times 10^9\]

Solution 2

A) \(60\,\text{mph} \to \text{m/s}\)

\[60 \frac{\text{mile}}{\text{hr}}\times\frac{1.6\,\text{km}}{1\,\text{mile}}\times\frac{1000\,\text{m}}{1\,\text{km}}\times\frac{1\,\text{hr}}{3600\,\text{s}}\approx 26.7\,\text{m/s}\]

B) \(0.5^\circ \to \text{arcsec}\)

\[0.5^\circ\times\frac{60\,\text{arcmin}}{1^\circ}\times\frac{60\,\text{arcsec}}{1\,\text{arcmin}}=1800\,\text{arcsec}\]

Solution 3

\[109^3 \approx (1.09\times10^2)^3 = 1.09^3\times10^6\approx 1.3\times10^6.\]

So the Sun’s volume is about 1.3 million Earth volumes.

Solution 4

\[29.8\,\text{km/s} = 2.98\times10^4\,\text{m/s}\]

One minute is \(60\,\text{s}\), so

\[\text{distance}=vt=(2.98\times10^4\,\text{m/s})(60\,\text{s})\approx 1.79\times10^6\,\text{m}.\]

That’s about 1800 km in one minute.

ASTR 101 • Lecture 2