From Ancient Skies to Kepler’s Laws

2,000 Years of Puzzles,

Three Elegant Rules

February 2, 2026

The planets wander

“The planets wander… sometimes they appeared to move backward.”

For 2,000 years, astronomers asked why.

Today’s Learning Objectives

By the end of today, you can:

- Explain retrograde motion as perspective + geometry

- Describe why models change (evidence + simplicity)

- State Kepler’s three laws

- Use Kepler III to relate \(P\) and \(a\) (ratio or Sun-only form)

- Distinguish empirical patterns from physical mechanisms

The Cosmic Puzzle

Why do planets move backward?

The Wanderers

Stars rise and set predictably.

But a handful of bright lights wandered among the fixed stars.

Sometimes they appeared to stop, reverse direction, then resume their journey.

Retrograde Motion — The Puzzle

What could cause a celestial body to move backward?

Spoiler: retrograde is an apparent motion — an illusion of perspective.

Like passing a slower car: it can look like it drifts backward against distant mountains.

The Highway Analogy

- Earth: faster, inner orbit

- Mars: slower, outer orbit

- Stars: distant background

As Earth passes Mars, Mars appears to drift backward against the stars.

But Mars never reverses its orbital direction.

Quick Check: Retrograde Motion

During Mars retrograde, Mars is actually moving:

- Backward in its orbit

- Forward in its orbit

- Stopped in space

- Falling toward the Sun

The Ancient Answer

Earth at the center

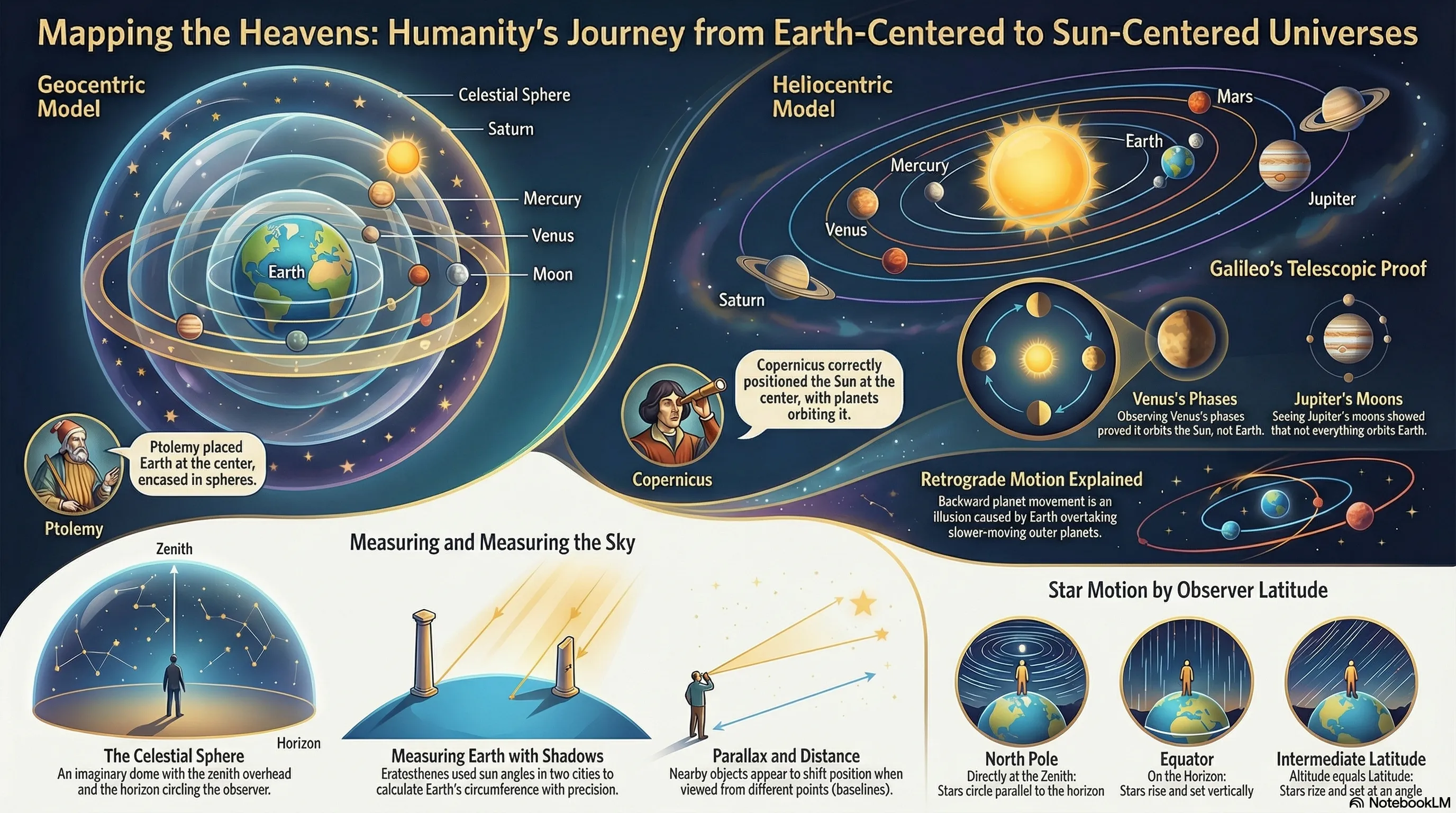

Ptolemy’s Geocentric Model (~150 CE)

Earth felt obviously central:

- We don’t feel Earth moving

- Stars rotate around us

- It matched everyday experience

The Epicycle Solution

Ptolemy proposed epicycles:

- Planet moves on a small circle (epicycle)

- Epicycle center moves on a larger circle (deferent)

- Combined motion can trace a loop (apparent retrograde)

Accurate, but complex: by medieval times the model needed dozens of circles.

Spot the Assumption

The geocentric model protected two assumptions:

Earth is stationary and central — we don’t feel motion, so we must not be moving

Circular motion is perfect — orbits must be circles because circles are “perfect”

What happens when we challenge these?

The Revolution Begins

Copernicus, Galileo, Tycho, Kepler

Copernicus (1543): A Simpler Idea

What if the Sun is at the center?

Geocentric (Ptolemy)

- Earth at center

- Epicycles needed for retrograde

- Dozens of circles

Heliocentric (Copernicus)

- Sun at center

- Retrograde = Earth passing outer planets

- No epicycles needed for retrograde!

Quick Check: The Copernican Shift

What was the key advantage of Copernicus’s heliocentric model?

- It was more accurate at predicting planetary positions

- It explained retrograde motion as geometry rather than requiring epicycles

- It was immediately accepted by the Church

- It used ellipses instead of circles

The Evidence Mounts

Galileo (1610) used telescopes to test models:

- Jupiter has moons — not everything orbits Earth

- Venus shows phases — consistent with heliocentrism

Evidence did not end the controversy.

Tycho Brahe: The Master Observer

20+ years of planetary observations

Greatest naked-eye observer in history

Tycho’s data was unprecedented in precision.

When he died in 1601, his observations passed to his young assistant…

Johannes Kepler

Kepler’s Laws

The Main Event

Kepler’s Struggle

Kepler inherited Tycho’s precision Mars data.

For years he tried circles.

An 8 arcminute mismatch forced a new shape: an ellipse.

Suddenly, the orbit fit.

Kepler’s First Law: The Shape of Orbits

Planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus.

What’s an Ellipse?

An ellipse has two special points called foci.

Key property: Sum of distances from any point to both foci is constant.

Eccentricity (\(e\)): How “squashed” the ellipse is

- \(e = 0\) means a perfect circle

- \(e\) close to 1 means a very elongated ellipse

Key Orbital Terms

| Term | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-major axis | \(a\) | Half the longest diameter; “average” orbital distance |

| Eccentricity | \(e\) | How “squashed” (0 = circle, near 1 = elongated) |

| Perihelion | \(r_p\) | Closest point to Sun; \(r_p = a(1-e)\) |

| Aphelion | \(r_a\) | Farthest point from Sun; \(r_a = a(1+e)\) |

The Sun sits at one focus, not the center.

Real Planetary Eccentricities

| Planet | Eccentricity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Venus | 0.007 | Nearly circular |

| Earth | 0.017 | Nearly circular |

| Mars | 0.093 | Noticeably elliptical |

| Mercury | 0.206 | Most eccentric planet |

| Halley’s Comet | 0.97 | Extremely elongated |

Most planets have nearly circular orbits — this is why Ptolemy got reasonably good results with circles.

Quick Check: Eccentricity

An orbit with eccentricity \(e = 0\) would be:

- A very elongated ellipse

- A perfect circle

- A parabola

- Impossible for a planet

Kepler’s Second Law: Orbital Speed

A line connecting a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

What “Equal Areas” Means

Perihelion (close to Sun):

- Smaller \(r\)

- Faster speed

Aphelion (far from Sun):

- Larger \(r\)

- Slower speed

Bottom line: planets speed up when closer to the Sun.

The Ice Skater Analogy

Think of an ice skater spinning with arms extended.

Arms in: spins faster

Arms out: spins slower

This is conservation of angular momentum.

Same idea: closer to the Sun means faster; farther means slower.

Real Example: Earth’s Orbit

| Position | Date | Distance from Sun | Earth’s Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perihelion | ~Jan 3 | 147.1 million km | 30.3 km/s |

| Aphelion | ~Jul 4 | 152.1 million km | 29.3 km/s |

Earth’s Orbit: What This Means

- Earth moves about 3% faster near perihelion than near aphelion.

- Northern Hemisphere winter is slightly shorter than summer.

Quick Check: Fastest Point

A planet is moving fastest when it is at:

- Aphelion (farthest from the Sun)

- Perihelion (closest to the Sun)

- Halfway between perihelion and aphelion

- The planet moves at constant speed

Predict First!

Before we see the law: if we double the orbital size (\(a \to 2a\)), the orbital period \(P\) becomes:

- \(2\times\)

- \(\approx 2.8\times\)

- \(4\times\)

- \(8\times\)

Kepler’s Third Law: The Period-Distance Relation

The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of its semi-major axis.

\[P^2 \propto a^3\]

Reading Kepler III

Let’s unpack the symbols:

- \(P\): orbital period (time per orbit)

- \(a\): semi-major axis (a measure of orbit size)

In plain English: if you increase orbit size, the period increases more than linearly.

Why Outer Planets Take Longer

Two effects compound:

They have farther to travel (larger orbit circumference)

They move slower (farther from the Sun means weaker gravitational pull)

These combine to give the precise \(P^2 \propto a^3\) relationship.

How to Use Kepler’s Third Law

Form 1: Ratio Method (recommended default)

\[\left(\frac{P_2}{P_1}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a_2}{a_1}\right)^3\]

Compare two objects orbiting the same central body.

Form 2: Sun-only Scaling

For objects orbiting the Sun, with \(P\) in years and \(a\) in AU:

\[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\]

Worked Example 1

Problem: A planet orbits the Sun at \(a = 4\) AU. What’s its period?

\[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{4\,\text{AU}}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3 = 64\]

\[P = \sqrt{64} \times 1\,\text{yr} = \boxed{8 \text{ years}}\]

Worked Example 2

Problem: A comet has orbital period \(P = 27\) years. What’s its semi-major axis?

\[\left(\frac{27\,\text{yr}}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\]

\[729 = \left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\]

\[a = \sqrt[3]{729} \times 1\,\text{AU} = \boxed{9 \text{ AU}}\]

Quick Check: Basic Calculation

An asteroid orbits the Sun at a distance of 4 AU. What is its orbital period?

- 4 years

- 8 years

- 16 years

- 64 years

Solar System Examples

| Planet | \(a\) (AU) | \(a^3\) | \(P\) (years) | \(P^2\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 3.51 | 1.88 | 3.53 |

Notice: \(a^3 \approx P^2\).

Solar System Examples (continued)

| Planet | \(a\) (AU) | \(a^3\) | \(P\) (years) | \(P^2\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 141 | 11.86 | 141 |

| Saturn | 9.54 | 868 | 29.46 | 868 |

Same pattern: \(a^3 \approx P^2\).

Quick Check: Scaling

If a planet’s orbital distance \(a\) increases by a factor of 4, its orbital period \(P\) increases by a factor of:

- 4

- 8

- 16

- 64

The Limits of Patterns

What Kepler could — and couldn’t — explain

What Kepler Could Do

- Predict planetary positions for centuries

- Calculate eclipses and conjunctions

- Replace dozens of epicycles with three elegant laws

For the first time, humanity had a precise mathematical description of planetary motion.

What Kepler Couldn’t Explain

Why ellipses? Why not circles?

Why do planets speed up when closer?

Why \(P^2 \propto a^3\)?

Does it work around other stars?

Empirical vs. Physical Laws

Empirical law: A pattern from data. Describes what happens.

Physical law: Explains why it happens.

Kepler’s laws are empirical.

They describe what planets do, beautifully and precisely.

But they don’t explain the underlying mechanism.

Quick Check: Empirical vs. Physical

Kepler’s laws are considered “empirical” rather than “physical” because:

- They are approximately true, not exactly true

- They describe patterns without explaining the underlying mechanism

- They only apply to the Solar System

- They were discovered before telescopes existed

The Setup for Newton

Newton (1687) gives the mechanism:

\[F = \frac{Gm_1m_2}{r^2}\]

Symbols:

- \(F\): force magnitude (N)

- \(m_1, m_2\): masses (kg)

- \(r\): separation between centers (m)

Key idea: \(F \propto 1/r^2\).

How Science Evolves

From epicycles to ellipses

The Power of Simplicity

| Era | Model | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy (~150 CE) | Geocentric + epicycles | Dozens of circles |

| Copernicus (1543) | Heliocentric + circles | Fewer circles, still complex |

| Kepler (1609-1619) | Heliocentric + ellipses | 3 laws, no epicycles |

Each step toward truth was also a step toward simplicity.

The Chain of Discovery

- Islamic scholars preserved Greek astronomy

- Copernicus proposed heliocentrism

- Tycho gathered precision data

- Kepler found the patterns

- Newton explained the physics

Key Takeaways

Retrograde is apparent (a geometry effect).

Kepler I: ellipses, Sun at a focus.

Kepler II: equal areas in equal times.

Key Takeaways (continued)

Kepler III: \(P^2 \propto a^3\) (use ratio or Sun-only form).

Kepler describes patterns; Newton explains mechanisms.

Better models are often simpler and more predictive.

Coming Up: Newton’s Gravity

Next lecture: Newton transforms patterns into physics.

We’ll see how one equation explains Kepler’s three laws.

Reading: Lecture 6 Reading Companion

Demo: Kepler’s Laws (Newton Mode): ../../../demos/keplers-laws/

Questions?

Kepler gave us the patterns.

Newton will give us the physics.

Numerical Verification

Checking our work with real data

Verifying Kepler III: Mars

Given data:

- Mars semi-major axis: \(a = 1.524\) AU

- Mars orbital period: \(P = 687\) days

Step 1: Convert period to years

\[P = 687 \text{ days} \times \frac{1 \text{ year}}{365.25 \text{ days}} = 1.881 \text{ years}\]

Step 2: Check \(P^2 = a^3\)

\[P^2 = (1.881)^2 = 3.538 \text{ yr}^2\]

\[a^3 = (1.524)^3 = 3.540 \text{ AU}^3\]

Match within rounding: \(3.538 \approx 3.540\) (0.06% difference from rounding)

Unit Analysis: Why \(\mathrm{yr}^2 = \mathrm{AU}^3\)?

Why does the shortcut look like time-squared equals distance-cubed?

The full physics statement is:

\[P^2 = \left(\frac{4\pi^2}{GM_\odot}\right) a^3\]

The constant \(\frac{4\pi^2}{GM_\odot}\) is doing the unit conversion.

Unit Analysis: What the Constant Means

- Sun-only shorthand: \(a\) in AU and \(P\) in years \(\Rightarrow P^2 \approx a^3\)

- Change units or change the central mass \(\Rightarrow\) use the full form (or the ratio method)

Unit Analysis: Why the Ratio Method Is Safe

- Compare two orbits around the same central mass: hidden constants cancel.

- It reduces unit mistakes and keeps the physics visible.

Verifying Kepler III: Jupiter

Given data:

- Jupiter semi-major axis: \(a = 5.203\) AU

- Jupiter orbital period: \(P = 4333\) days

Convert and verify:

\[P = 4333 \text{ days} \times \frac{1 \text{ yr}}{365.25 \text{ days}} = 11.86 \text{ yr}\]

\[P^2 = (11.86)^2 = 140.7 \text{ yr}^2\]

\[a^3 = (5.203)^3 = 140.9 \text{ AU}^3\]

Match within rounding: \(140.7 \approx 140.9\)

Common Unit Mistake: Mixing Units

Mistake (unit mismatch):

“\(a = 778\) million km, \(P = 12\) years, so \(P^2 = 144\) and \(a^3 = 4.7 \times 10^{26}\)… they don’t match!”

Fix (convert first):

\[a = 778 \times 10^6 \text{ km} \times \frac{1 \text{ AU}}{1.496 \times 10^8 \text{ km}} = 5.20 \text{ AU}\]

Then compare \(P^2\) (in yr\(^2\)) to \(a^3\) (in AU\(^3\)).

Common Unit Mistake: Forgetting Squares and Cubes

Mistake (wrong powers):

“\(P = 12\) years and \(a = 5.2\) AU, so \(12 = 5.2\)… wrong!”

Fix: Kepler III is about \(P^2\) and \(a^3\).

In Sun-only units (years and AU), you can do a quick consistency check:

\[(12)^2 = 144 \quad \text{and} \quad (5.2)^3 \approx 141\]

Deeper Dive

For curious minds

How Fast at Perihelion vs Aphelion?

Kepler II says planets move faster when closer to the Sun. But how much faster?

From conservation of angular momentum:

\[v_p \times r_p = v_a \times r_a\]

where \(v_p\) = speed at perihelion, \(v_a\) = speed at aphelion.

Perihelion vs Aphelion: Symbols

What the symbols mean:

- \(r_p, r_a\) are the perihelion/aphelion distances (same distance units as \(a\))

- \(a\) is the semi-major axis (a distance)

- \(e\) is eccentricity (unitless)

Speed Ratio from Eccentricity

Starting from conservation of angular momentum:

\[v_p \times r_p = v_a \times r_a\]

Rearranging:

\[\frac{v_p}{v_a} = \frac{r_a}{r_p} = \frac{a(1+e)}{a(1-e)} = \frac{1+e}{1-e}\]

Sanity check: if \(e=0\) (a circle), then \(r_p=r_a\) and \(\frac{v_p}{v_a}=1\).

Worked Example: Mercury’s Speed Ratio

Mercury has eccentricity \(e = 0.206\).

\[\frac{v_p}{v_a} = \frac{1 + 0.206}{1 - 0.206} = \frac{1.206}{0.794} = 1.52\]

Mercury moves 52% faster at perihelion than at aphelion!

Compare to Earth (\(e = 0.017\)):

\[\frac{v_p}{v_a} = \frac{1.017}{0.983} = 1.035\]

Earth only varies by 3.5% — nearly circular orbit.

The Vis-Viva Equation (Preview)

Newton will show us that orbital speed at distance \(r\) is:

\[v = \sqrt{GM\left(\frac{2}{r} - \frac{1}{a}\right)}\]

Vis-Viva: Symbols and Sanity Check

- \(v\): speed

- \(r\): current distance

- \(a\): semi-major axis

- \(M\): central mass

Assumptions: two-body, Newtonian gravity, spherical bodies.

Sanity check: if the orbit is circular, then \(r=a\) and \(v=\sqrt{GM/a}\) is constant.

Vis-Viva: Perihelion vs Aphelion

At perihelion (\(r = r_p = a(1-e)\)):

\[v_p = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{a} \cdot \frac{1+e}{1-e}}\]

At aphelion (\(r = r_a = a(1+e)\)):

\[v_a = \sqrt{\frac{GM}{a} \cdot \frac{1-e}{1+e}}\]

We’ll derive this properly in L6 with Newton’s laws. For now, notice how \(e\) controls the speed variation.

ASTR 101 - Lecture 5 - Dr. Anna Rosen