The Cosmic Messenger

Light Carries Information

February 9, 2026

You’ve never touched a star.

You never will.

Yet you know its temperature, composition, age, mass, and motion.

How?

Light is the universe’s messenger

Light is the universe’s messenger.

Every photon has a story:

- Its wavelength reveals temperature

- Spectral shifts reveal motion

- Specific wavelengths reveal composition

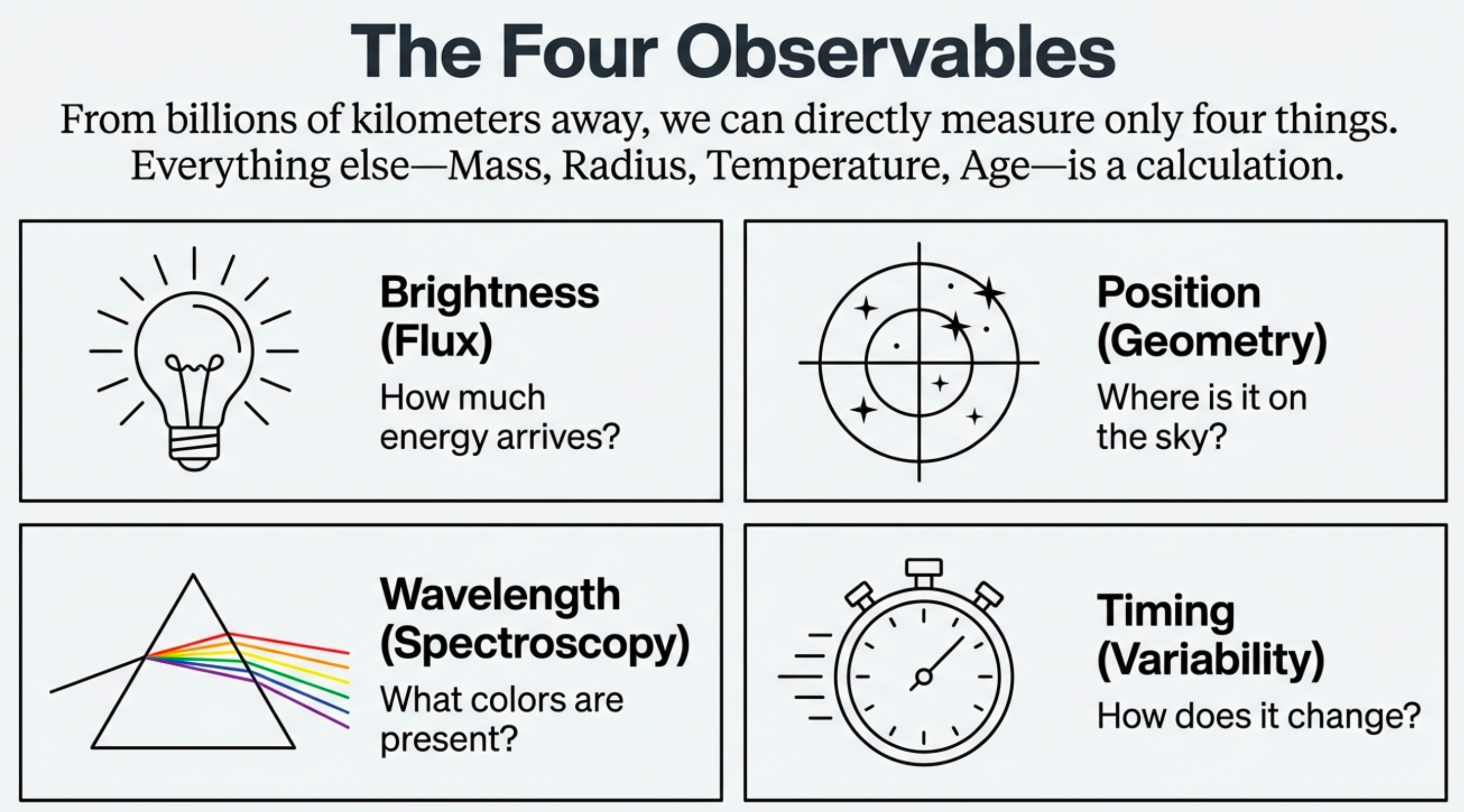

From Observables to Inference

For any star, we measure:

- brightness

- position

- wavelength

- timing

Then infer temperature, composition, motion, and planetary context.

Today’s Learning Objectives

By the end of today, you can:

- Describe light as an electromagnetic wave (\(c = \lambda \nu\))

- Identify the major regions of the electromagnetic spectrum

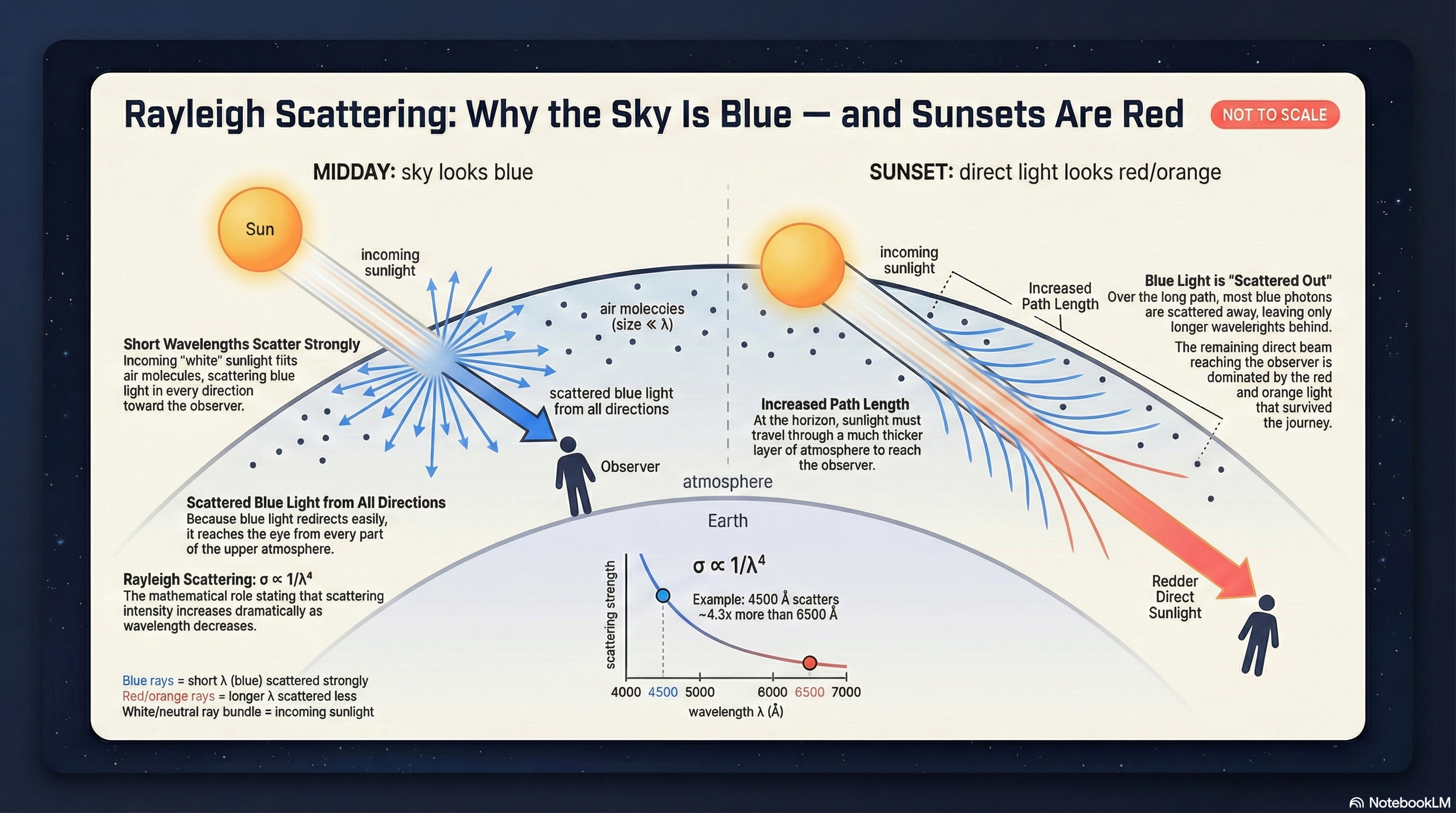

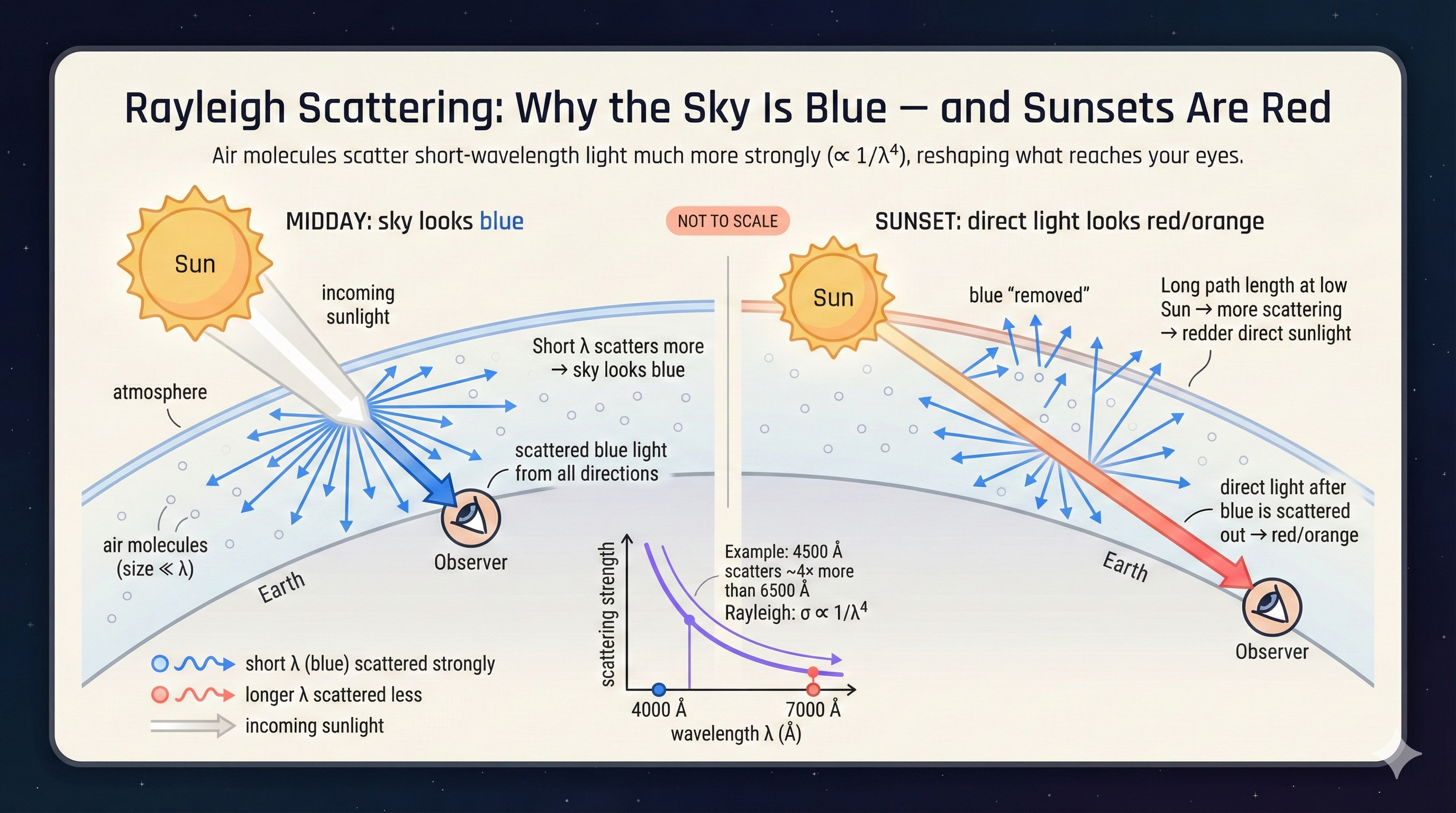

- Explain why the sky is blue and sunsets are red

Today’s Learning Objectives (continued)

By the end of today, you can:

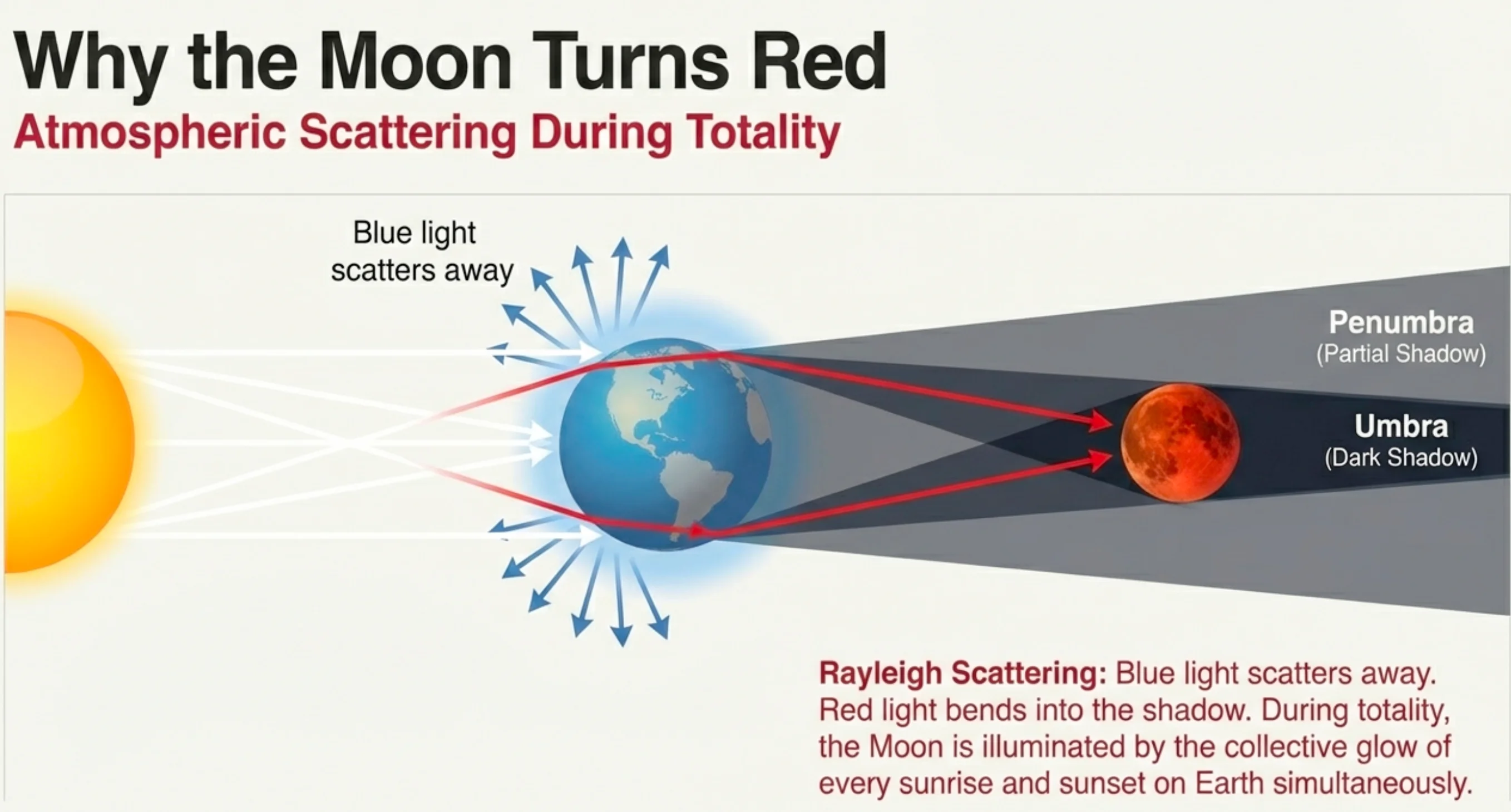

- Explain why lunar eclipses produce a red Moon

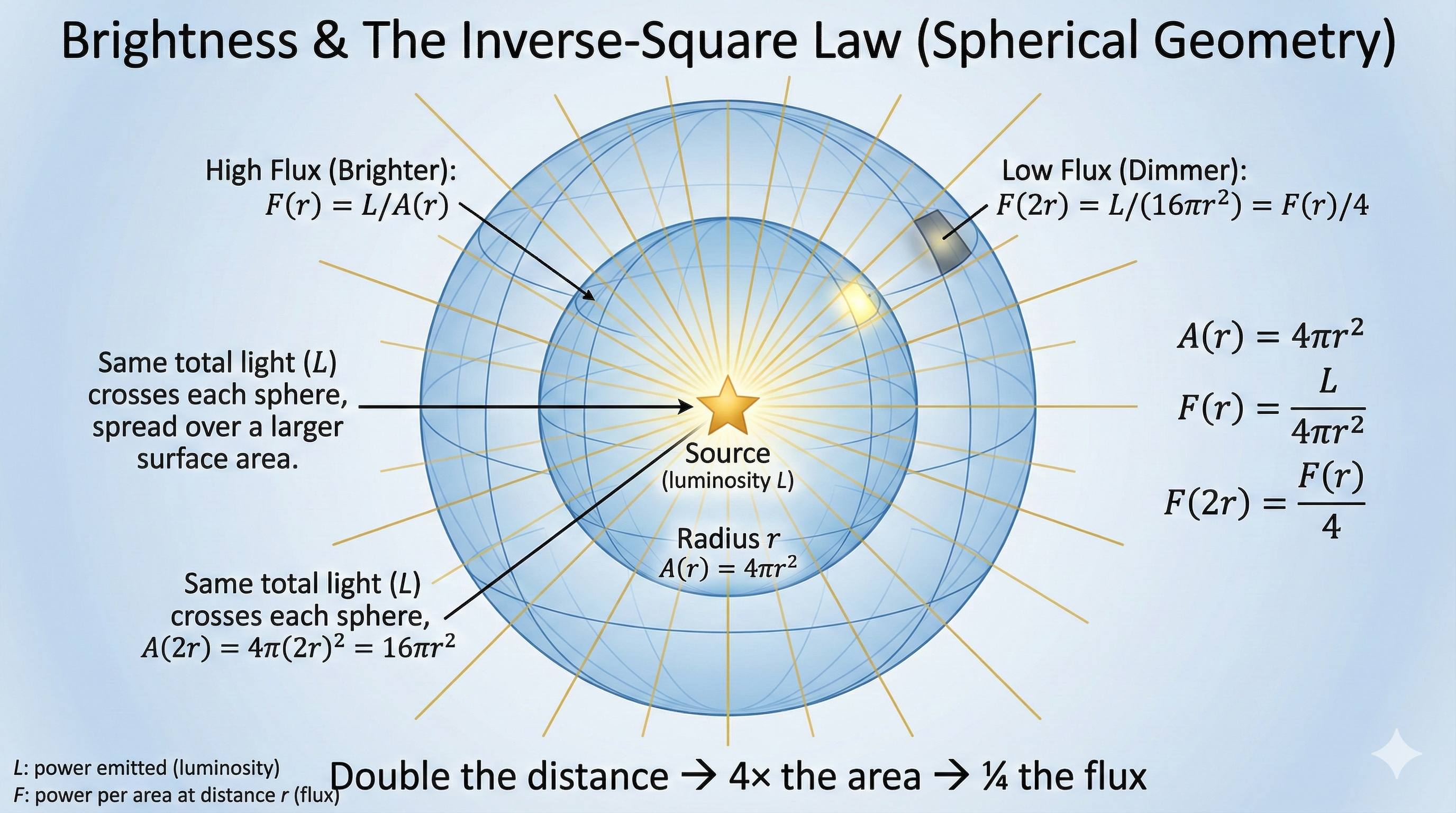

- Apply the inverse-square law for light intensity (\(I \propto 1/r^2\))

- Infer temperature, composition, and motion from starlight observations

Where We Left Off

Lectures 5-6: Motion reveals mass

- Kepler found patterns in planetary motion

- Newton explained those patterns with gravity

- By measuring orbits, we can “weigh” invisible objects

Today: Light reveals everything else — temperature, composition, velocity, distance.

Part 1: What Is Light?

The electromagnetic wave

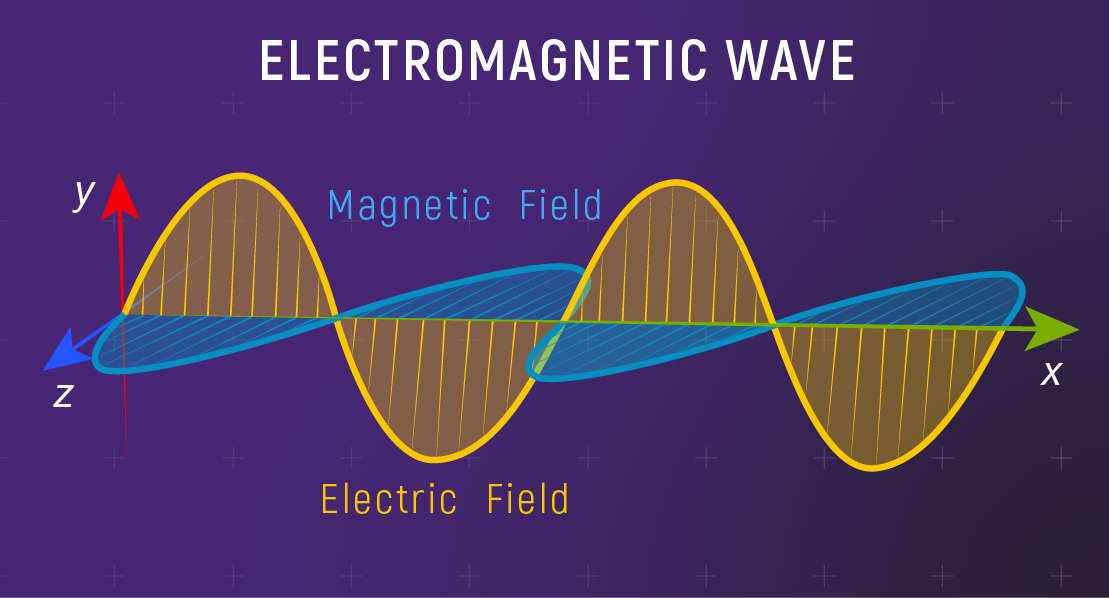

Light Is an Electromagnetic Wave

Electromagnetic wave:

Self-propagating oscillation of electric and magnetic fields.

Unlike sound or ocean waves — no medium needed!

Light travels perfectly through the vacuum of space.

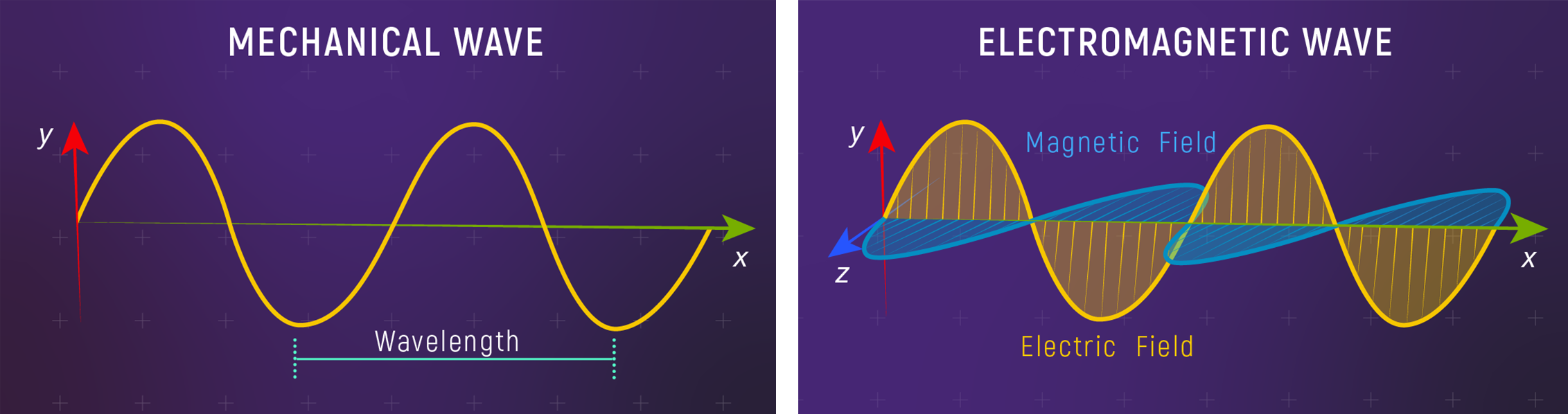

Mechanical vs Electromagnetic Waves

EM waves need no material medium, so light crosses interstellar vacuum.

Two Key Properties

| Property | Symbol | What it measures | Units |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wavelength | \(\lambda\) | Distance between wave crests | meters (m) or nanometers (nm) |

| Frequency | \(\nu\) | Wave crests passing per second | hertz (Hz) |

Wave relation: \(c = \lambda \nu\) (with \(c = 3 \times 10^8\ \mathrm{m/s}\))

Predict First!

Without doing math: if the wavelength doubles (\(\lambda \to 2\lambda\)), the frequency \(\nu\) becomes…

- \(2\times\)

- \(\frac{1}{2}\times\)

- unchanged

- \(4\times\)

The Wave Equation

\[c = \lambda \nu\]

Since \(c\) is constant:

- Longer wavelength means lower frequency.

- Shorter wavelength means higher frequency.

Wavelength and frequency carry the same information — two ways to describe the same wave.

Quick Check: Wavelength and Frequency

If one type of light has twice the wavelength of another, it has:

- Twice the frequency

- Half the frequency

- The same frequency

- Four times the frequency

The Electromagnetic Spectrum

More than meets the eye

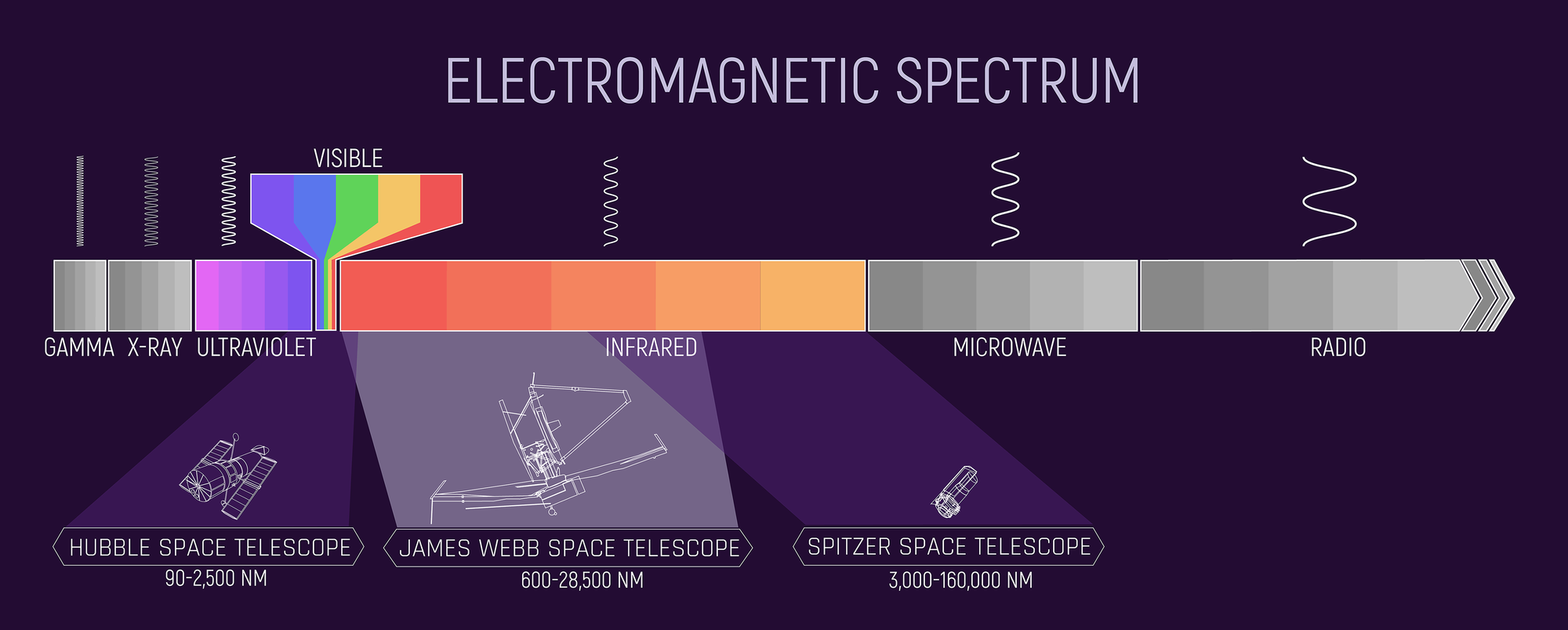

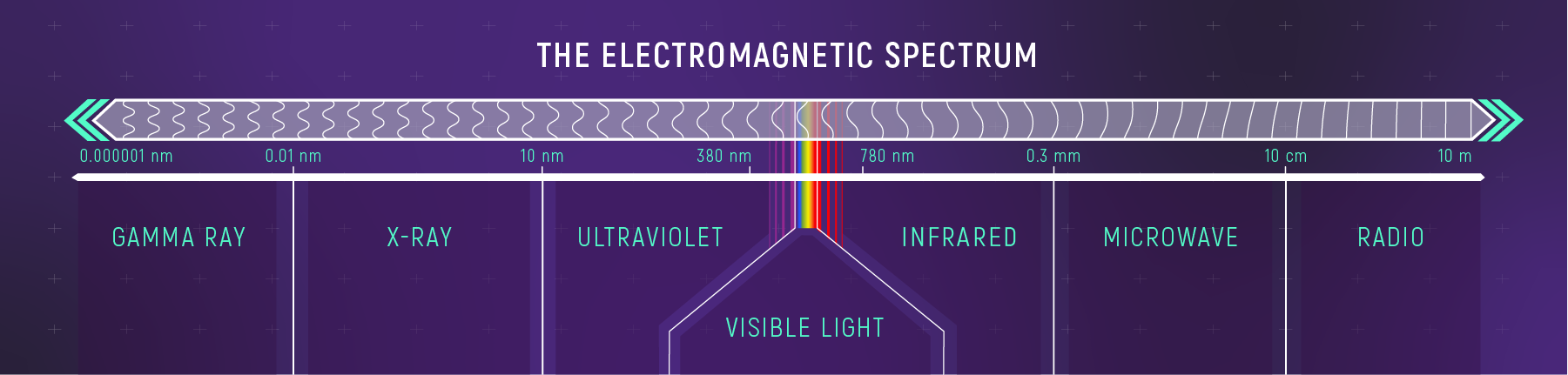

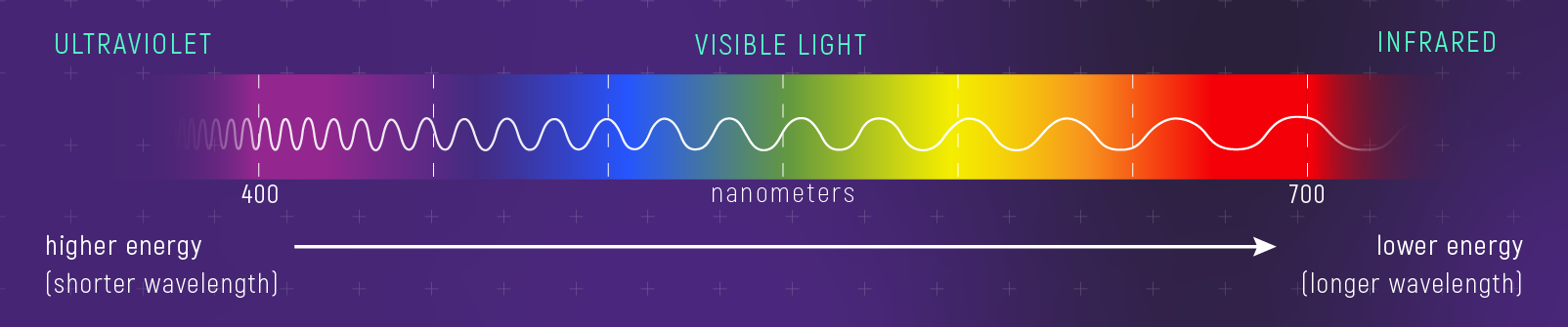

Visible Light Is a Tiny Sliver

“Visible light” — the colors we see — is just a tiny fraction of the full spectrum.

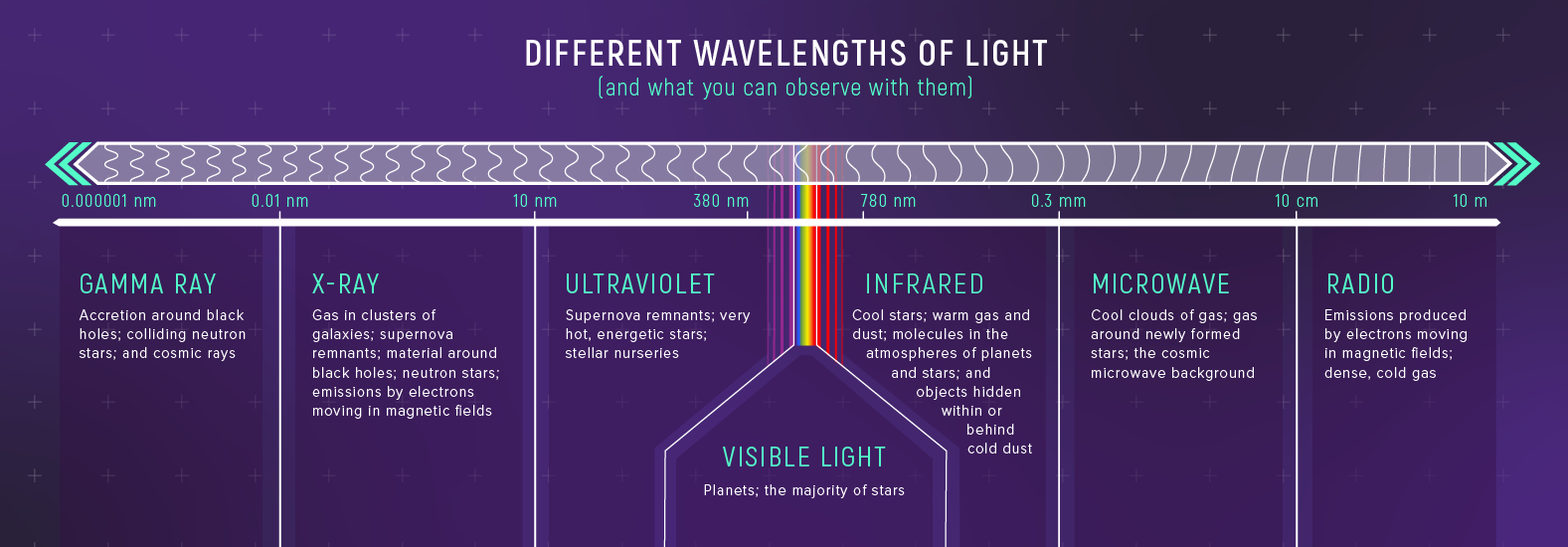

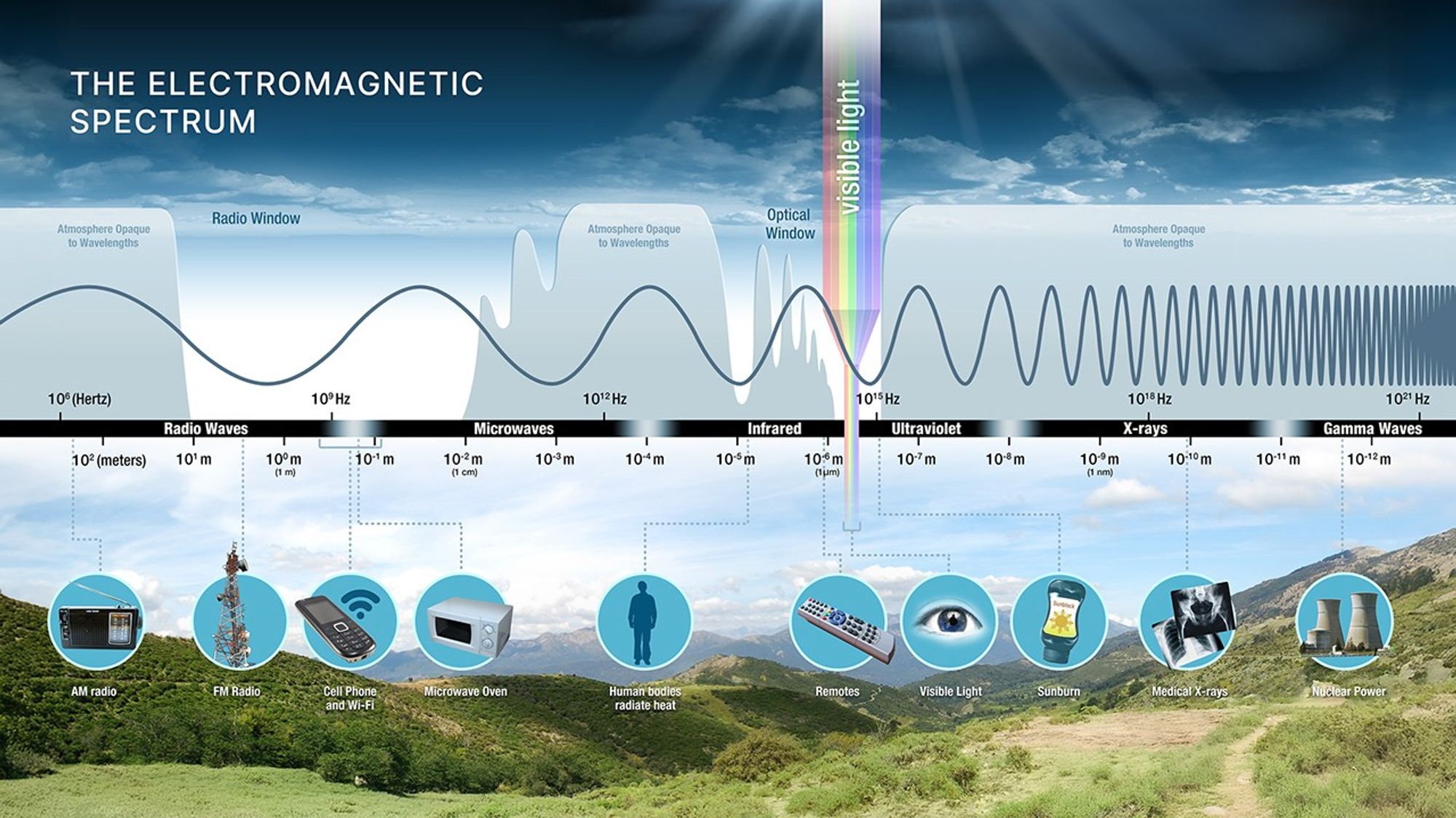

Full Electromagnetic Spectrum

Visible light is only a narrow window in a much larger spectrum. Different wavelength bands trace different physics.

Spectrum Through Earth’s Atmosphere

Radio and optical windows reach the ground; many other wavelengths require space telescopes.

Atmospheric transmission determines which observatories must be in space.

The Full Spectrum (1/2)

| Region | Wavelength | Astronomical uses |

|---|---|---|

| Radio | > 10 cm | Mapping hydrogen, pulsars |

| Microwave | 1 mm – 10 cm | CMB, cold dust |

| Infrared | 700 nm – 1 mm | Dust, cool stars |

| Visible | 400 – 700 nm | Direct imaging |

The Full Spectrum (2/2)

| Region | Wavelength | Astronomical uses |

|---|---|---|

| Ultraviolet | 10 – 400 nm | Hot gas |

| X-ray | 0.01 – 10 nm | Black holes, neutron stars |

| Gamma ray | < 0.01 nm | Supernovae, gamma-ray bursts |

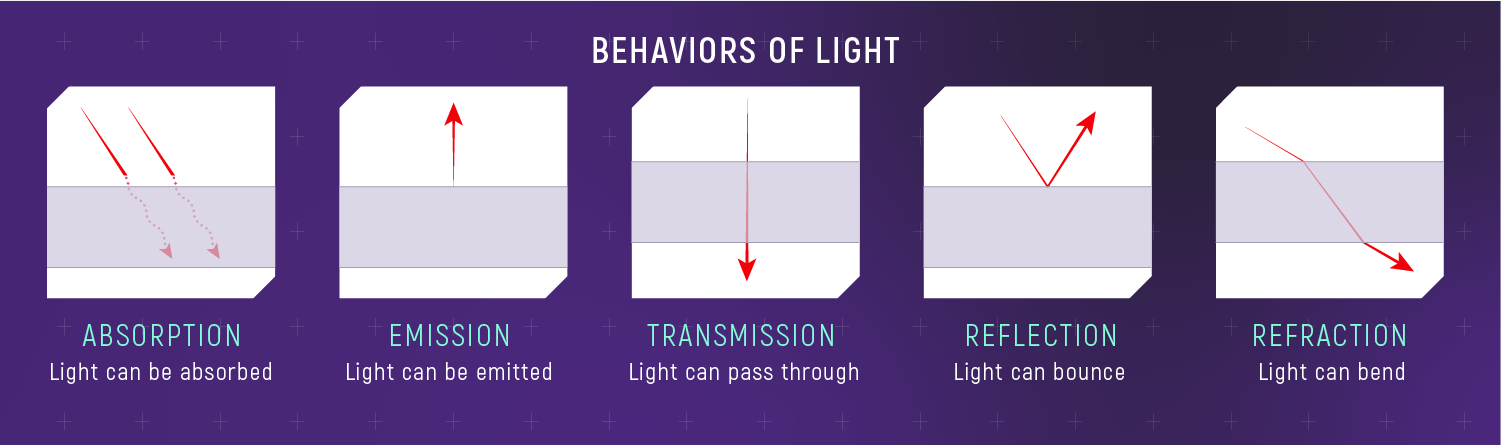

How Light Interacts with Matter

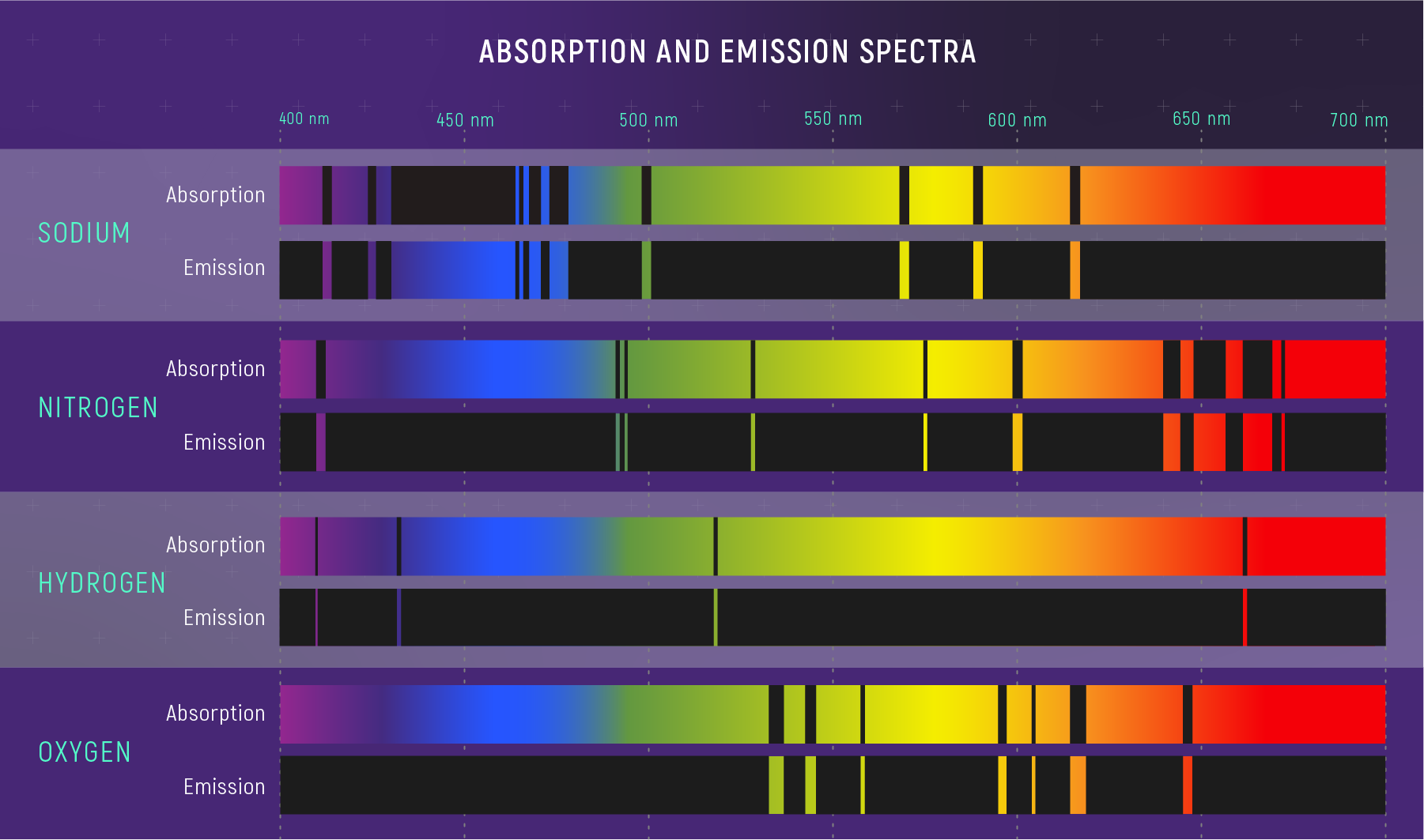

- Absorption removes specific wavelengths.

- Emission adds specific wavelengths.

- Reflection, refraction, and transmission change light paths.

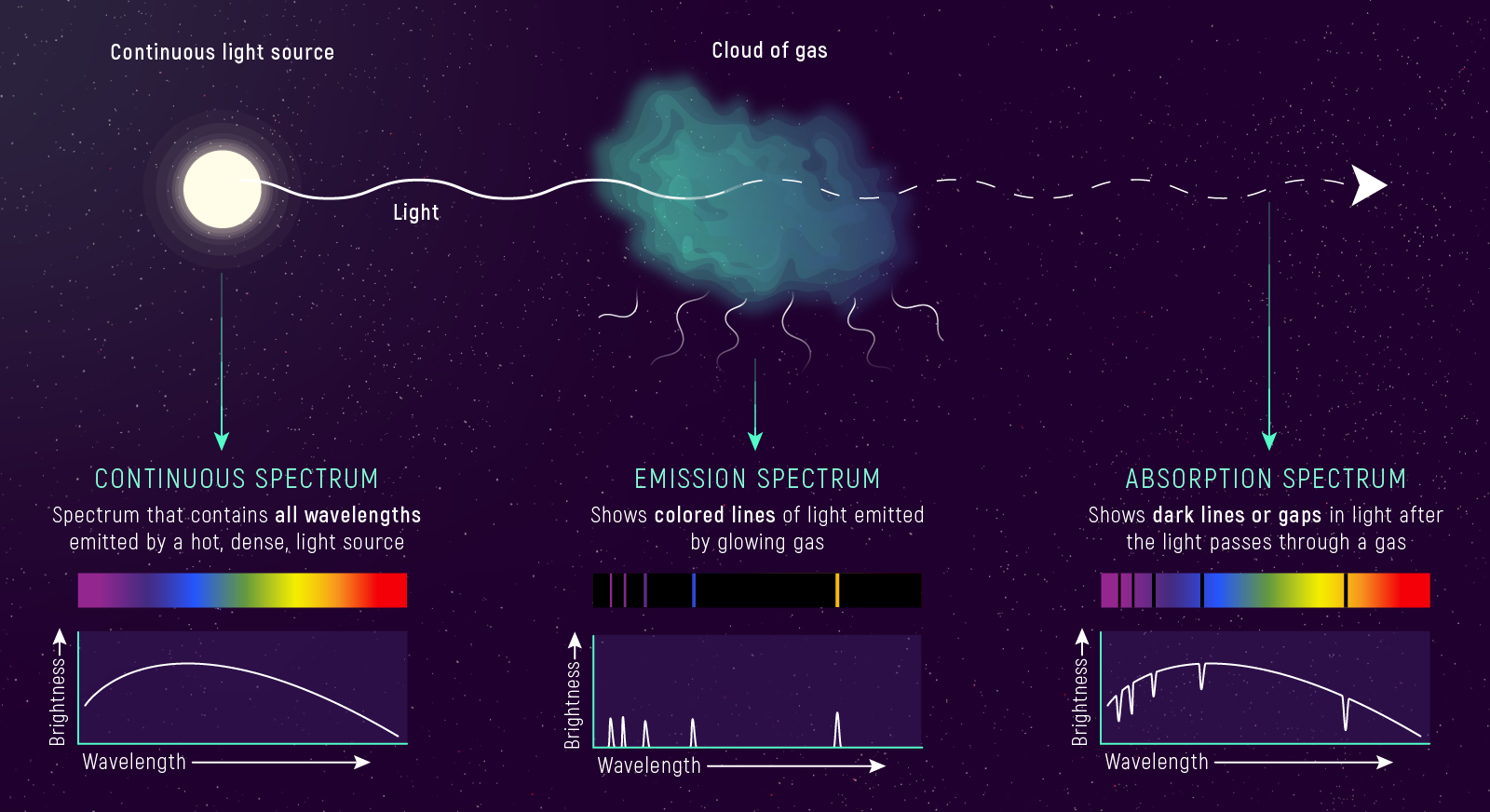

Three Spectra Astronomers Use

- Continuous: dense, hot source.

- Emission-line: hot, thin gas.

- Absorption-line: continuum through cooler gas.

Absorption and Emission Fingerprints

- Same element means the same line wavelengths.

- Absorption lines are dark where photons are removed.

- Emission lines are bright where photons are added.

EM Spectrum in Astronomy

Different wavelength bands map to different physical regimes.

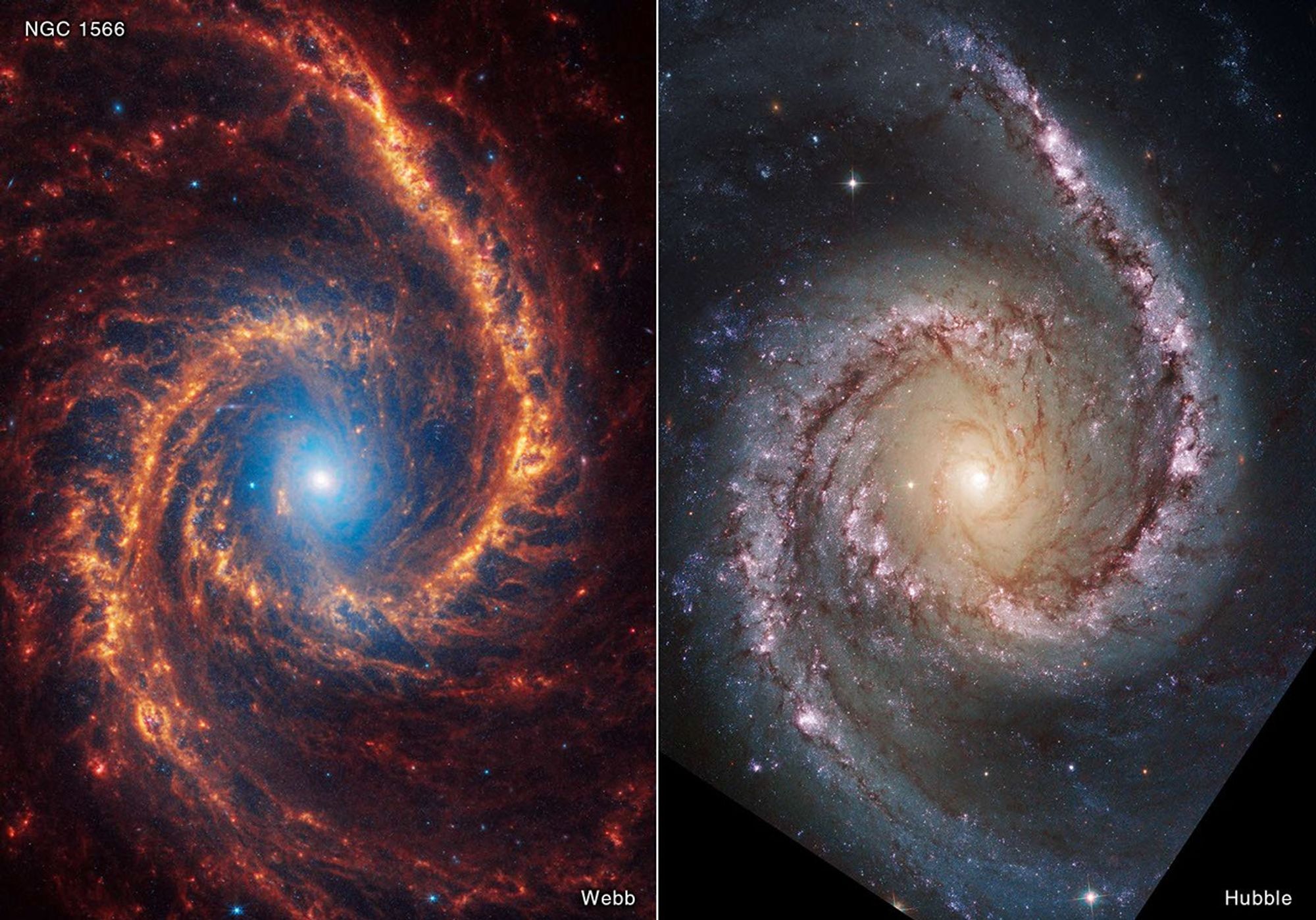

Same Object, Different Wavelengths

The universe looks different at every wavelength.

Crab Nebula Across Wavelengths

One object, multiple observables, multiple physical inferences.

Quick Check: Ordering the Spectrum

Which correctly orders these from longest to shortest wavelength?

- Gamma rays, X-rays, UV, Visible, Infrared, Radio

- Radio, Infrared, Visible, UV, X-rays, Gamma rays

- Visible, UV, Infrared, Radio, X-rays, Gamma rays

- Microwave, Radio, Visible, Infrared, Gamma rays

Quick Check: Multiwavelength Astronomy

Why do astronomers observe the same object at different wavelengths?

- Different telescopes are in different locations

- Different wavelengths reveal different physical processes

- It’s cheaper to use old telescopes

- Visible light is too faint

The Speed of Light

\(c = 299,792,458\) m/s

~300,000 km/s

This is the cosmic speed limit.

Nothing with mass can reach it.

And because light has finite speed…

looking out in space is looking back in time.

Light-Travel Time (1/2)

| Object | Distance | Light-travel time |

|---|---|---|

| Moon | 384,000 km | 1.3 s |

| Sun | 150 million km | 8 min |

| Proxima Centauri | 4.2 light-years | 4.2 yr |

Light-Travel Time (2/2)

| Object | Distance | Light-travel time |

|---|---|---|

| Andromeda Galaxy | 2.5 million light-years | 2.5 million yr |

| Distant galaxies | Billions of light-years | Billions of yr |

When we observe the most distant galaxies, we’re seeing the early universe directly.

Quick Check: Light Travel Time

When we observe the Andromeda Galaxy (2.5 million light-years away), we see it as it was:

- Right now, in real time

- 2.5 years ago

- 2.5 million years ago

- Billions of years ago

Part 2: Why Is the Sky Blue?

Rayleigh scattering

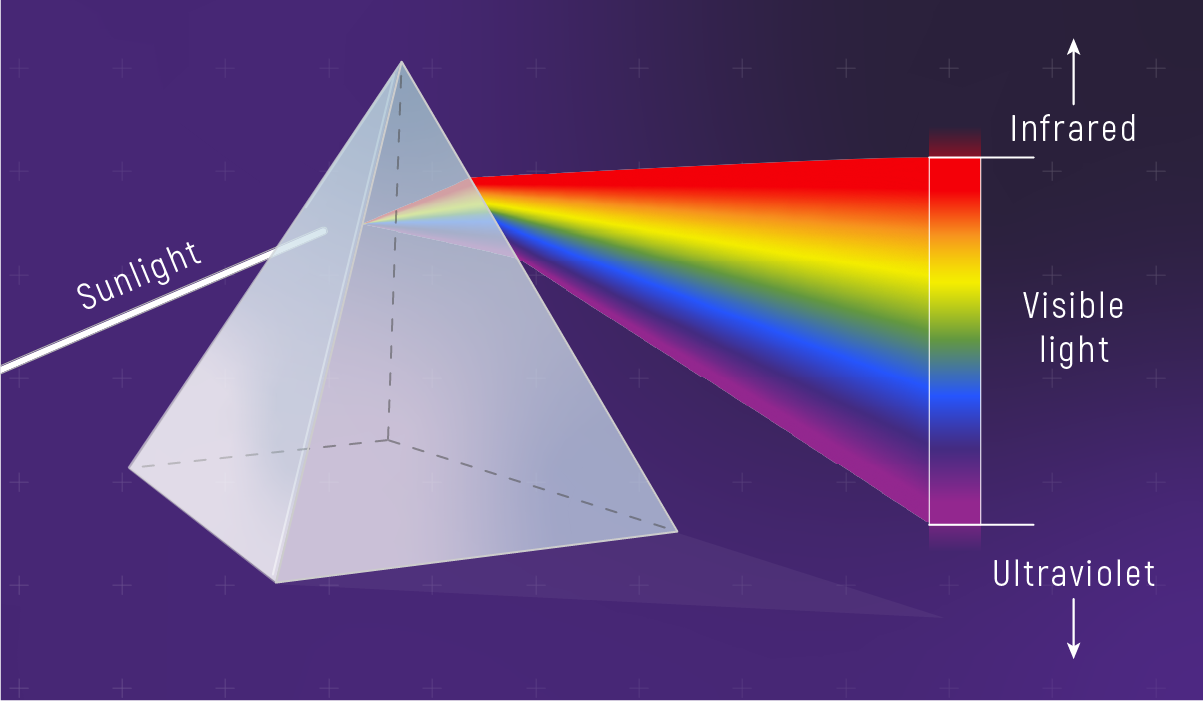

Sunlight Is All Colors

Sunlight is white light — a mix of all visible wavelengths.

So why does the sky favor blue?

Rayleigh Scattering

\[\text{Scattering} \propto \frac{1}{\lambda^4}\]

Shorter wavelengths scatter MUCH more.

Valid when the scatterers are much smaller than the wavelength (e.g., atmospheric molecules).

Comparing blue (\(\lambda \approx 450\) nm) and red (\(\lambda \approx 700\) nm):

\[\left(\frac{700}{450}\right)^4 \approx 6\]

Blue scatters about \(6\times\) more than red!

Why the Sky Is Blue and Sunsets Are Red

Sky is blue: blue photons scatter in many directions, so they reach your eyes from across the sky.

Sunsets are red: along a longer atmospheric path, blue is scattered away and red/orange light remains.

Rayleigh Scattering in Real Sky Data

The same wavelength-dependent scattering shows up in real atmospheric observations.

Quick Check: Rayleigh Scattering

Blue light scatters more than red light because:

- Blue light is faster than red light

- Shorter wavelengths scatter more in Rayleigh scattering (\(\propto 1/\lambda^4\))

- Air molecules are blue

- The Sun emits more blue light

Quick Check: Sunsets

Sunsets appear red because:

- The Sun turns red as it sets

- The atmosphere filters out red light, leaving blue

- Blue light has been scattered away on the long path through atmosphere

- Dust particles block the blue

The Blood Moon

Same physics, cosmic scale

Lunar Eclipse Puzzle

During a total lunar eclipse, the Moon doesn’t go dark — it turns deep red.

Why doesn’t it go completely dark?

The Moon is in Earth’s shadow — no direct sunlight reaches it…

Earth’s Atmosphere as Filter

- Sunlight passes through Earth’s atmosphere

- Blue light scatters away (Rayleigh!)

- Only red light makes it through

- That red light bends toward the Moon

Quick Check: Blood Moon

During a total lunar eclipse, the Moon appears red because:

- The Moon reflects Mars’s light

- Earth’s atmosphere scatters blue away, letting red sunlight reach the Moon

- The Moon’s surface is actually red

- The Sun becomes cooler during eclipses

Part 3: Light Intensity

Another inverse-square law

Inverse-Square Law for Light

\[I \propto \frac{1}{r^2}\]

Double your distance, receive 1/4 the intensity

Why? Light spreads over spheres.

Sphere area \(= 4\pi r^2\), so intensity drops as \(1/r^2\).

Same geometric argument as gravity (L6)!

Distance and Brightness

| Distance Change | Intensity Change |

|---|---|

| \(2\times\) farther | 1/4 as bright |

| \(3\times\) farther | 1/9 as bright |

| \(10\times\) farther | 1/100 as bright |

| \(100\times\) farther | 1/10,000 as bright |

If we know true luminosity and measure apparent brightness, we can calculate distance!

Quick Check: Distance and Brightness

A star appears 16 times fainter than an identical star nearby. How much farther away is the faint star?

- \(4\times\) farther

- \(16\times\) farther

- \(8\times\) farther

- \(2\times\) farther

Quick Check: Two Stars

Star A is \(5\times\) farther away than Star B. If they have the same luminosity, Star A appears:

- \(5\times\) fainter

- \(10\times\) fainter

- \(25\times\) fainter

- \(125\times\) fainter

Key Takeaways (1/2)

Light is an electromagnetic wave: \(c = \lambda \nu\).

The EM spectrum spans radio to gamma rays.

Rayleigh scattering: shorter wavelengths scatter more (\(\propto 1/\lambda^4\)).

Light intensity follows the inverse-square law: \(I \propto 1/r^2\).

Key Takeaways (2/2)

Blue sky and red sunsets are the same scattering physics.

Lunar eclipses are red for the same reason (sunset light).

Light is the astronomer’s primary tool: temperature, composition, motion, distance.

The Course Connection

L5-L6: Motion reveals mass

L7-L8: Light reveals temperature

L9: Spectral lines reveal composition and motion

Together: We can measure a star’s temperature, mass, composition, and velocity — all without touching anything.

Coming Up: Temperature from Light

Next lecture: Everything glows.

Hotter objects glow bluer and brighter.

By analyzing the spectrum, we can read an object’s temperature from billions of kilometers away.

Reading: Lecture 8 Reading Companion

Demo: Explore the EM Spectrum: ../../../demos/em-spectrum/

Numerical Verification

Checking the wave equation and scattering

Verifying \(c = \lambda \nu\)

Given: Red light has wavelength \(\lambda = 700\) nm. What’s its frequency?

Step 1: Convert wavelength to meters

\[\lambda = 700 \text{ nm} \times \frac{10^{-9} \text{ m}}{1 \text{ nm}} = 7.00 \times 10^{-7} \text{ m}\]

Step 2: Solve for frequency

\[\nu = \frac{c}{\lambda} = \frac{3.00 \times 10^8 \text{ m/s}}{7.00 \times 10^{-7} \text{ m}}\]

\[\nu = 4.29 \times 10^{14} \text{ Hz} = 4.29 \times 10^{14} \text{ s}^{-1}\]

Unit check: \(\frac{\text{m/s}}{\text{m}} = \frac{1}{\text{s}} = \text{Hz}\)

Frequency Comparison Across the Spectrum

| Type | Wavelength | Frequency | Calculation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radio (FM) | 3 m | \(10^8\) Hz | \(\frac{3 \times 10^8}{3} = 10^8\) |

| Microwave | 1 cm | \(3 \times 10^{10}\) Hz | \(\frac{3 \times 10^8}{10^{-2}}\) |

| Red light | 700 nm | \(4.3 \times 10^{14}\) Hz | \(\frac{3 \times 10^8}{7 \times 10^{-7}}\) |

| Blue light | 450 nm | \(6.7 \times 10^{14}\) Hz | \(\frac{3 \times 10^8}{4.5 \times 10^{-7}}\) |

| X-ray | 1 nm | \(3 \times 10^{17}\) Hz | \(\frac{3 \times 10^8}{10^{-9}}\) |

Pattern: Shorter wavelength means higher frequency (always!).

Rayleigh Scattering: Full Calculation

How much more does blue scatter than red?

Blue: \(\lambda_b = 450\) nm, Red: \(\lambda_r = 700\) nm

Scattering ratio:

\[\frac{\text{Scattering}_{\text{blue}}}{\text{Scattering}_{\text{red}}} = \frac{1/\lambda_b^4}{1/\lambda_r^4} = \left(\frac{\lambda_r}{\lambda_b}\right)^4\]

\[= \left(\frac{700 \text{ nm}}{450 \text{ nm}}\right)^4 = (1.556)^4\]

\[= 5.86 \approx 6\]

Blue light scatters about \(6\times\) more than red light.

Units cancel: \((\text{nm}/\text{nm})^4\) is dimensionless.

Why Not Violet?

Violet (\(\lambda \approx 400\) nm) scatters even MORE than blue:

\[\left(\frac{700}{400}\right)^4 = (1.75)^4 = 9.4\]

Violet scatters \(9\times\) more than red!

Why Not Violet? (continued)

So why isn’t the sky violet?

- The Sun emits less violet than blue.

- Our eyes are less sensitive to violet.

- Some violet is absorbed by ozone.

Result: We perceive the scattered light as blue, not violet.

Inverse-Square Law: Star Distance Problem

Problem: Star A appears \(100\times\) fainter than Star B. If they’re identical, how much farther is Star A?

From inverse-square law:

\[\frac{I_A}{I_B} = \frac{r_B^2}{r_A^2}\]

\[\frac{1}{100} = \frac{r_B^2}{r_A^2}\]

Inverse-Square Law: Solving the Distance Ratio

Problem: Star A appears \(100\times\) fainter than Star B. If they’re identical, how much farther is Star A?

Solving for distance ratio:

\[\frac{r_A}{r_B} = \sqrt{100} = 10\]

Star A is \(10\times\) farther away.

Note: We don’t need absolute distances — just the ratio!

Light Travel Time: Proxima Centauri

Given: Proxima Centauri is 4.24 light-years away. Express this in km.

Step 1: How far does light travel in 1 year?

\[d_{1\text{yr}} = c \times t = (3.00 \times 10^5 \text{ km/s}) \times (1 \text{ year})\]

Convert 1 year to seconds:

\[1 \text{ yr} = 365.25 \text{ days} \times 24 \text{ hr/day} \times 3600 \text{ s/hr} = 3.156 \times 10^7 \text{ s}\]

\[d_{1\text{ly}} = 3.00 \times 10^5 \times 3.156 \times 10^7 = 9.47 \times 10^{12} \text{ km}\]

Distance to Proxima Centauri:

\[d = 4.24 \times 9.47 \times 10^{12} \text{ km} = 4.01 \times 10^{13} \text{ km}\]

Photon Energy

The quantum nature of light — essential foundation for Lectures 8 and 9

Wavelength and Photon Energy

Shorter wavelength means higher photon energy.

Light as Particles: Photons

Light behaves as both a wave and a particle.

Each particle of light — a photon — carries energy:

\[E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda}\]

Where:

- \(h = 6.626 \times 10^{-34}\ \mathrm{J\,s}\) (Planck’s constant)

- \(c = 3.00 \times 10^8\ \mathrm{m/s}\)

- \(hc = 1.986 \times 10^{-25}\ \mathrm{J\,m}\)

Photon Energy: Useful Forms

In Joules (SI units):

\[E = \frac{1.986 \times 10^{-25}\ \mathrm{J\,m}}{\lambda\ \text{(in meters)}}\]

In electron-volts (more convenient for atoms):

\[E = \frac{1240\ \mathrm{eV\,nm}}{\lambda\ \text{(in nm)}}\]

Example: Red photon (\(\lambda = 620\) nm)

\[E = \frac{1240\ \mathrm{eV\,nm}}{620\ \text{nm}} = 2.0\ \text{eV}\]

Where Does \(1240\ \mathrm{eV\,nm}\) Come From?

\[hc = (6.626 \times 10^{-34}\ \mathrm{J\,s}) \times (3.00 \times 10^8\ \mathrm{m/s})\]

\[= 1.988 \times 10^{-25}\ \mathrm{J\,m}\]

Convert J to eV:

\[1 \text{ eV} = 1.602 \times 10^{-19} \text{ J}\]

\[hc = \frac{1.988 \times 10^{-25}\ \mathrm{J\,m}}{1.602 \times 10^{-19}\ \mathrm{J/eV}} = 1.241 \times 10^{-6}\ \mathrm{eV\,m}\]

Convert m to nm:

\[hc = 1.241 \times 10^{-6}\ \mathrm{eV\,m} \times \frac{10^9\ \text{nm}}{1\ \text{m}} = 1241\ \mathrm{eV\,nm}\]

We round to \(1240\ \mathrm{eV\,nm}\) for convenience.

Photon Energies Across the Spectrum (1/2)

| Light | Wavelength | Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| Radio | 1 m = \(10^9\) nm | \(1.24 \times 10^{-6}\) |

| Infrared | 10,000 nm | 0.124 |

| Red | 620 nm | 2.0 |

| Blue | 450 nm | 2.76 |

Photon Energies Across the Spectrum (2/2)

| Light | Wavelength | Energy (eV) |

|---|---|---|

| UV | 100 nm | 12.4 |

| X-ray | 1 nm | 1,240 |

Shorter wavelength means higher photon energy.

Why UV Causes Sunburn

It’s not about intensity — it’s about energy per photon.

Shorter-wavelength photons carry more energy per photon.

UV photons can break chemical bonds (sunburn risk). Visible photons usually cannot.

Questions?

Light is the universe’s messenger.

Every photon carries information.

ASTR 101 - Lecture 7 - Dr. Anna Rosen