flowchart LR

A[Question] --> B[Dimensional Analysis]

B -->|Valid?| C[Ratio Method]

C -->|Compare| D[Unit Conversion]

D -->|Calculate| E[OOM Check]

E -->|Sensible?| F[Answer]

Lecture 2: Tools of the Trade

Mastering Astrophysical Reasoning

January 22, 2026

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture, you will be able to:

- Use dimensional analysis to verify equation validity

- Apply the ratio method to compare astronomical quantities

- Convert between SI and CGS unit systems

- Perform order-of-magnitude estimations

Every physics mistake leaves a fingerprint.

Spot the Problem

A student calculates the orbital period of Mars using:

\[P = \frac{r^2}{GM} \rightarrow P = 3.5 \times 10^{14} \text{ ... something.}\]

Before you calculate anything:

Can you tell this equation is wrong?

The Fingerprint

Check the Dimensions: period \(P\) should be time: \([T]\).

- \(r^2\) has dimensions \([L]^2\)

- \(GM\) has dimensions \([L^3 T^{-2}]\)

\[\frac{r^2}{GM} = \frac{[L^2]}{[L^3 T^{-2}]} = [L^{-1} T^2]\]

That’s not time. It’s “time squared per length” — its physically meaningless.

The equation is guaranteed wrong. No calculator needed.

Stop & Solve 1: Dimensional Detective

Which formula(s) could represent an orbital period \(P\)?

Select all with dimensions of \([T]\) (time).

| Formula | |

|---|---|

| a) | \(P \propto \frac{r^2}{GM}\) |

| b) | \(P \propto \sqrt{\frac{r^3}{GM}}\) |

| c) | \(P \propto \frac{r}{\sqrt{GM}}\) |

| d) | \(P \propto \sqrt{\frac{GM}{r^3}}\) |

Given

\([G] = M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}\), \(\;[r]=L\), \(\;[M]=M\)

Work rule: Track \([L],[M],[T]\) only — no numbers.

Stop & Solve 1 — Solution

We want \([P]=[T]\). Use \([GM]=[L^3T^{-2}]\) because \([G][M]=[M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}][M]=[L^3T^{-2}]\).

- \(\dfrac{r^2}{GM} \sim \dfrac{[L^2]}{[L^3T^{-2}]}=[L^{-1}T^2]\) ❌ not time

- \(\sqrt{\dfrac{r^3}{GM}} \sim \sqrt{\dfrac{[L^3]}{[L^3T^{-2}]}}=\sqrt{[T^2]}=[T]\) ✅

- \(\dfrac{r}{\sqrt{GM}} \sim \dfrac{[L]}{\sqrt{[L^3T^{-2}]}}=\dfrac{[L]}{[L^{3/2}T^{-1}]}=[L^{-1/2}T]\) ❌ not time

- \(\sqrt{\dfrac{GM}{r^3}} \sim \sqrt{\dfrac{[L^3T^{-2}]}{[L^3]}}=\sqrt{[T^{-2}]}=[T^{-1}]\) ❌ this is a frequency scale

Only option 2 has dimensions of time.

What You’ll Do Today

Using only dimensional analysis, you will:

- Derive how planets orbit (Kepler’s Third Law)

- Estimate the size of a black hole’s event horizon

- Preview why white dwarfs get smaller when they gain mass (HW derivation)

No calculus. No memorizing formulas. Just dimensional logic.

About That “Math Person” Thing

You might be thinking: “I’m not a math person.”

Here’s the truth:

- Your brain physically changes when you learn hard things

- The discomfort you feel? That’s neurons forming new connections

- “Math person” is learned, not born—and it can be unlearned

This isn’t talent. It’s a skill you’re about to learn.

The Challenge: Points of Light

Stars appear as mere points. Is that faint red glow a tiny nearby dwarf or a massive distant supergiant?

We can’t visit them. We can’t weigh them directly.

So how do we know anything about them?

We need a toolkit that extracts physics from limited data.

Today’s Toolkit

Four methods that turn “points of light” into physics:

- Dimensional Analysis — Is this equation even possible?

- The Ratio Method — How does this compare to something known?

- Unit Conversions — What’s the numeric value in useful units?

- Order-of-Magnitude — Does this answer make sense?

These aren’t math drills—they’re inference tools.

Why we’re doing this

Math as a telescope 🔭

Astronomy is the art of inferring physical reality from limited measurements.

Today’s superpower: units + dimensions catch mistakes before they become beliefs.

- We usually can’t touch the system — we observe light, motion, and time.

- We build simplified models that connect measurements to physics.

- We sanity-check (dimensions, units, scaling, limits) so we don’t compute nonsense confidently.

A quick disclaimer about “borrowed” equations

We will use a few equations before we derive them

Later this semester (and in your physics sequence) you’ll learn where they come from.

Rules for today

- Treat them as reliable tools.

- You do not need deep physical intuition yet.

- You do need to know what each symbol means, and what the equation is claiming.

How to read any equation (without panic)

The decoding ritual (we’ll use this all semester)

For any equation, ask:

- What does it predict? (output)

- What does it depend on? (inputs)

- What happens if a variable increases? (direction + scaling)

- What assumptions are hiding? (“only if…”)

- Does it pass unit and limit checks?

The four-tool workflow

Your survival kit 🧰

- Dimensional analysis → “Could this formula possibly be right?”

- Ratio method → “Compare without big-number pain.”

- Unit conversion → “Translate SI ↔︎ CGS fluently.”

- Order-of-magnitude → “Sanity-check reality.”

Tool 1: Dimensional Analysis

The “smoke detector” for physics

Units vs. Dimensions

![Split diagram contrasting UNITS (The Map) showing ruler, stopwatch, and weights labeled as 'human inventions, fungible, arbitrary' versus DIMENSIONS (The Territory) showing [L], [T], [M] symbols labeled as 'physical realities, invariant, fundamental'. Footer states physical laws must hold regardless of units used.](../../../assets/images/module-01/units-vs-dimensions-nblm.png)

The Fundamental Trio

Every physical quantity in this course is built from three ingredients:

| Dimension | Symbol | Example (CGS) |

|---|---|---|

| Length | \([L]\) | cm |

| Mass | \([M]\) | g |

| Time | \([T]\) | s |

Units are conventions (cm vs AU).

Dimensions are invariant physical DNA.

Derived Quantities (CGS)

| Quantity | Dimensions | CGS Unit |

|---|---|---|

| Velocity | \([LT^{-1}]\) | cm/s |

| Acceleration | \([LT^{-2}]\) | cm/s\(^2\) |

| Force | \([MLT^{-2}]\) | dyne (g cm/s\(^2\)) |

| Energy | \([ML^2T^{-2}]\) | erg (g cm\(^2\)/s\(^2\)) |

| Pressure | \([ML^{-1}T^{-2}]\) | dyne/cm\(^2\) |

Building Blocks

![Visual equation builder showing how Mass [M], Length [L], and Time [T] combine like building blocks: Velocity = L/T → [L][T]^-1, Acceleration = velocity/time → [L][T]^-2, Force = mass × acceleration → [M][L][T]^-2, Energy = force × distance → [M][L]²[T]^-2. Includes sanity check: if your energy calculation has dimensions [M][L][T]^-1, you missed a velocity term.](../../../assets/images/module-01/fundamental-dims-nblm.png)

The Smoke Detector Test

If you calculate a star’s mass and your answer has dimensions of time…

The physics is wrong.

You don’t need a calculator to know something’s broken.

Prediction: Dimensions of \(G\)

Newton’s law of gravity: \[F = \frac{GMm}{r^2}\]

What’s in this equation?

- \(F\): gravitational force between two masses

- \(G\): gravitational constant (how strong is gravity?)

- \(M\): mass of the central object (e.g., star)

- \(m\): mass of the orbiting object (e.g., planet with \(m \ll M\))

- \(r\): distance between the two masses

Before I show you: What dimensions must \(G\) have?

A. \([MLT^{-2}]\) B. \([M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}]\) C. \([L^3T^{-2}]\) D. \([MT^{-2}]\)

Worked Example: What are the dimensions of \(G\)?

Newton’s law of gravity: \[F = \frac{GMm}{r^2}\]

Known dimensions:

- \([F] = MLT^{-2}\)

- \([M], [m] = M\)

- \([r] = L\)

Rearrange: \(G = \dfrac{F r^2}{M m}\)

\[ \begin{aligned} [G] &= \frac{[F][r]^2}{[M][m]} = \frac{(MLT^{-2})(L^2)}{M \cdot M} \\[0.5em] &= \frac{ML^3T^{-2}}{M^2} = M^{-1}L^3T^{-2} \\[0.5em] &\rightarrow \boxed{[G]= M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}} \end{aligned} \]

Constants Are Physical Quantities

![Diagram explaining that constants like G and c are not just numbers but conversion factors. Shows c (speed of light) with dimensions [L][T]^-1 as the universal speed limit, and G (gravitational constant) derived from Newton's law with dimensions [M]^-1[L]^3[T]^-2. Highlights the inverse mass term that allows gravity to cancel mass.](../../../assets/images/module-01/physical-constants-nblm.png)

Check Yourself: Orbital Period

Kepler’s Third Law gives us: \[P \propto \sqrt{\frac{r^3}{GM}}\]

Question: Verify the dimensions work out to time \([T]\).

But Wait—How Did We Get That Formula?

We just verified Kepler’s Law.

But can we derive it from first principles?

Yes. Using only dimensional analysis.

The Protocol

Case A: Orbital period — setup

What can the orbital period depend on?

We want a formula for orbital period \(P\): “time for one orbit.”

Ingredients (allowed today):

- Orbit size \(r\) → \([L]\)

- Central mass \(M\) → \([M]\)

- Gravity constant \(G\) → \([M^{-1}L^{3}T^{-2}]\)

Goal: \[[P] = [T]\]

Equation meaning (gloss)

- \(P\): how long the orbit takes

- \(r\): how big the orbit is

- \(M\): how much mass is pulling

- \(G\): how strongly mass gravitates

Case A: Orbital period — solve (slow)

Assume: \(P \propto r^{a}M^{b}G^{c}\)

Convert to dimensions: \[[T] = [L]^a[M]^b[M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}]^c\] \[= [L]^{a+3c}[M]^{b-c}[T]^{-2c}\]

Match exponents:

- \(T:\; 1=-2c \Rightarrow c=-\tfrac12\)

- \(M:\; 0=b-c \Rightarrow b=-\tfrac12\)

- \(L:\; 0=a+3c \Rightarrow a=\tfrac32\)

\[\boxed{P \propto \sqrt{\frac{r^{3}}{GM}}}\]

Case A: Orbital period — interpretation

\[P \propto \sqrt{\frac{r^{3}}{GM}}\]

- \(r \uparrow\) makes \(P\) grow fast: \(P \propto r^{3/2}\)

- \(M \uparrow\) makes \(P\) shrink: stronger gravity → faster orbit

- Unit check intuition: bigger distance → longer time ✅

What it predicts

Given \(r\), \(M\), \(G\), it predicts \(P\).

What it’s saying

“Farther orbits take much longer. More mass makes orbits faster.”

Optional “later this semester” add-on: \[P = 2\pi\sqrt{\frac{r^{3}}{GM}} \quad \text{(exact for circular orbits)}\]

Stop & Solve 2: Ratio Method — Mars’ Year

Goal

Use ratios to avoid big-number arithmetic.

For planets orbiting the Sun, Kepler scaling gives: \[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2=\left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\]

Mars has \(a = 1.52\,\text{AU}\).

- Estimate \(P_{\text{Mars}}\) in years (1 significant figure is fine).

- Write one sentence explaining why \(P\) grows faster than linearly with distance.

Hint: \(1.5^3 \approx 3.4\). Then take a square root.

Stop & Solve 2 — Solution

\[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2=\left(1.52\right)^3 \approx 3.5 \Rightarrow \frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}} \approx \sqrt{3.5}\approx 1.9\]

\[P_{\text{Mars}} \approx 1.9\,\text{yr}\]

Interpretation (sample): Farther orbits feel weaker gravity and have more distance to travel; the combination produces \(P \propto a^{3/2}\), so period grows quickly with distance.

Case B: Black hole horizon — setup

What sets the “point of no return”?

We want a characteristic radius \(R\) for a black hole (a length scale).

Ingredients:

- Mass \(M\) → \([M]\)

- Gravity \(G\) → \([M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}]\)

- Speed of light \(c\) → \([LT^{-1}]\)

Goal: \[[R]=[L]\]

Equation meaning (gloss)

- \(c\): speed limit of the universe

- if escape speed reaches \(c\), light can’t escape

- \(R\): the radius where that happens

Case B: Black hole horizon — solve (slow)

Assume: \(R \propto G^{a}M^{b}c^{d}\)

(\(c = 3 \times 10^{8}\,\text{m/s}\), speed of light)

Dimensions: \[[L] = [M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}]^a[M]^b[LT^{-1}]^d\] \[= [L]^{3a+d}[M]^{-a+b}[T]^{-2a-d}\]

Match exponents:

- \(T:\;0=-2a-d \Rightarrow d=-2a\)

- \(M:\;0=-a+b \Rightarrow b=a\)

- \(L:\;1=3a+d \Rightarrow a=1\)

\[\boxed{R \propto \frac{GM}{c^2}}\]

Later-semester “exact” result (Schwarzschild): \(R_s=\frac{2GM}{c^2}\)

Case B: Black hole horizon — interpretation

\[R_s=\frac{2GM}{c^2}\]

- \(M \uparrow\) → \(R_s \uparrow\) linearly

- bigger \(c\) would shrink horizons (faster universe makes trapping harder)

- this sets a length scale where escape becomes impossible

What it predicts

Given \(M\), it predicts the black hole’s horizon size.

What it’s saying

“More mass → bigger region where gravity wins against light.”

Checkpoint 1 (retrieval)

- If \(F \propto \dfrac{GMm}{r^2}\), what are the dimensions of \(F\)?

- If the mass \(M\) doubles, how does \(R_s\) change?

Checkpoint 1 — solutions

- \([F] = [MLT^{-2}]\)

- \(R_s \propto M\), so if \(M\) doubles, \(R_s\) doubles.

Tool 2: The Ratio Method

Escaping the “big number” trap

The Problem with Big Numbers

Mass of the Sun: \(M_\odot = 2 \times 10^{33}\) g Mass of the Earth: \(M_\oplus = 6 \times 10^{27}\) g

Subtraction fails

\[M_\odot - M_\oplus = 1.999... \times 10^{33} \text{ g}\]

Useless. Still a giant, meaningless number.

Division works

\[\frac{M_\odot}{M_\oplus} \approx 333{,}000\]

The Sun is 333,000× more massive than Earth.

Ratios give relative scale. Absolute numbers often don’t.

The Cancellation Trick

Most physical laws are proportionality relationships: \[A = kB^n\]

When comparing two systems: \[\frac{A_2}{A_1} = \frac{kB_2^n}{kB_1^n} = \left(\frac{B_2}{B_1}\right)^n\]

The constant \(k\) cancels!

We don’t need to know \(G\), \(\pi\), or \(\sigma\) numerically.

Worked Example: Solar Volume

The Sun’s radius is 109 times Earth’s radius: \[\frac{R_\odot}{R_\oplus} = 109\]

Volume of a sphere: \(V = \frac{4}{3}\pi R^3\)

How many Earths fit inside the Sun?

\[\frac{V_\odot}{V_\oplus} = \left(\frac{R_\odot}{R_\oplus}\right)^3 = 109^3 \approx 1.3 \times 10^6\]

Over 1 million Earths!

Scaling Intuition

| Scaling | Physical Meaning | Example |

|---|---|---|

| \(A \propto B^2\) | Area | Surface area, intensity |

| \(A \propto B^3\) | Volume | Mass (if density constant) |

| \(A \propto B^{-2}\) | Inverse-square | Gravity, light intensity |

Small changes in input → big changes in output when \(n > 1\)

Concept Check: Surface Area Scaling

If you double a nebula’s radius, by what factor does its surface area increase?

Solution: Surface Area

\[SA \propto R^2\] \[\frac{SA_2}{SA_1} = \left(\frac{2R}{R}\right)^2 = 4\]

Factor of 4. (The \(4\pi\) cancels.)

Tool 3: Unit Conversions

Why astronomers use CGS

First: Scientific Notation Crash Course

Numbers in astronomy get… absurd.

Mass of the Sun: \[1{,}989{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000{,}000 \text{ g}\]

Nobody writes that. Instead:

\[M_\odot = 2 \times 10^{33} \text{ g}\]

Reading Scientific Notation

\[a \times 10^n\]

| Part | What it means |

|---|---|

| \(a\) | Coefficient (1–10) |

| \(10^n\) | “Move decimal \(n\) places” |

| \(n > 0\) | Big number (move right) |

| \(n < 0\) | Small number (move left) |

Example: \(3.0 \times 10^{10}\) = 30,000,000,000 = 30 billion

Rules of the Game

Multiplication: Add exponents \[10^3 \times 10^5 = 10^{3+5} = 10^8\]

Division: Subtract exponents \[\frac{10^{33}}{10^{27}} = 10^{33-27} = 10^6\]

Powers: Multiply exponents \[(10^3)^2 = 10^{3 \times 2} = 10^6\]

SI Prefixes: The Language of Scale

| Prefix | Symbol | Power | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| tera | T | \(10^{12}\) | THz (infrared) |

| giga | G | \(10^{9}\) | GHz (radio) |

| mega | M | \(10^{6}\) | Mpc (galaxy distances) |

| kilo | k | \(10^{3}\) | km (everyday) |

| centi | c | \(10^{-2}\) | cm (CGS!) |

| milli | m | \(10^{-3}\) | mm (wavelengths) |

| micro | μ | \(10^{-6}\) | μm (infrared) |

| nano | n | \(10^{-9}\) | nm (visible light) |

Astronomy Lives at the Extremes

| Scale | Value | Context |

|---|---|---|

| \(10^{-13}\) cm | Atomic nucleus | Where fusion happens |

| \(10^{-5}\) cm | Wavelength of light | What we detect |

| \(10^{10}\) cm | Solar radius | A typical star |

| \(10^{18}\) cm | 1 parsec | Distance scale |

| \(10^{28}\) cm | Observable universe | Cosmic horizon |

That’s 41 orders of magnitude. Scientific notation isn’t optional—it’s survival.

The CGS System

Astronomy uses CGS (centimeter-gram-second), not SI.

| Base | CGS | SI |

|---|---|---|

| Length | cm | m |

| Mass | g | kg |

| Time | s | s |

Derived units:

- Energy: erg (not Joule)

- Force: dyne (not Newton)

- Luminosity: erg/s (not Watt)

Why CGS?

SI (Physics textbooks)

\[L_\odot = 3.8 \times 10^{26} \text{ W}\]

CGS (Astrophysics)

\[L_\odot = 3.8 \times 10^{33} \text{ erg/s}\]

Both are correct. CGS is the community standard for astrophysics.

The Fractional Identity

The key insight: \(1 \text{ m} = 100 \text{ cm}\) means:

\[\frac{100 \text{ cm}}{1 \text{ m}} = 1\]

Multiplying by 1 doesn’t change the physics.

It only changes how we write the number.

Stop & Solve 3: Unit Conversions = Algebra

Goal

Convert units by multiplying by 1 (factor-label method).

3A. Speed (SI → CGS)

Convert \(30\,\mathrm{km/s}\) to \(\mathrm{cm/s}\). Show the chain: \[30\,\frac{\mathrm{km}}{\mathrm{s}} \times\frac{10^3\,\mathrm{m}}{1\,\mathrm{km}} \times\frac{10^2\,\mathrm{cm}}{1\,\mathrm{m}}\]

3B. Power / Luminosity units

Convert \(3.8\times 10^{26}\,\mathrm{W}\) to \(\mathrm{erg/s}\).

Given: \(1\,\mathrm{W}=1\,\mathrm{J/s}\), and \(1\,\mathrm{J}=10^7\,\mathrm{erg}\)

Stop & Solve 3 — Solution

3A

\[30\,\frac{\mathrm{km}}{\mathrm{s}} \times\frac{10^3\,\mathrm{m}}{1\,\mathrm{km}} \times\frac{10^2\,\mathrm{cm}}{1\,\mathrm{m}} =30\times 10^5\,\frac{\mathrm{cm}}{\mathrm{s}} =3\times 10^6\,\mathrm{cm/s}\]

3B

\[3.8\times 10^{26}\,\mathrm{W} =3.8\times 10^{26}\,\mathrm{J/s} =3.8\times 10^{26}\times 10^7\,\mathrm{erg/s} =3.8\times 10^{33}\,\mathrm{erg/s}\]

Example 2: Energy (Exponents Matter!)

How many erg in 1 Joule?

\[1 \text{ J} = 1 \text{ kg} \cdot \text{m}^2 \cdot \text{s}^{-2}\]

\[= (10^3 \text{ g})(10^2 \text{ cm})^2 \text{ s}^{-2}\]

\[= 10^3 \times 10^4 \text{ g cm}^2 \text{ s}^{-2} = 10^7 \text{ erg}\]

Example 3: The Stefan-Boltzmann Constant

SI: \(\sigma = 5.67 \times 10^{-8}\) W m\(^{-2}\) K\(^{-4}\)

Convert to CGS:

- W → erg/s: \(\times 10^7\)

- m\(^{-2}\) → cm\(^{-2}\): \(\times 10^{-4}\)

\[\sigma = 5.67 \times 10^{-8} \times 10^7 \times 10^{-4} = 5.67 \times 10^{-5} \text{ erg cm}^{-2} \text{ s}^{-1} \text{ K}^{-4}\]

Key Conversions to Memorize

| Quantity | CGS Value |

|---|---|

| 1 parsec | \(3.09 \times 10^{18}\) cm |

| 1 AU | \(1.50 \times 10^{13}\) cm |

| Solar mass \(M_\odot\) | \(2.0 \times 10^{33}\) g |

| Solar radius \(R_\odot\) | \(7.0 \times 10^{10}\) cm |

| Solar luminosity \(L_\odot\) | \(3.8 \times 10^{33}\) erg/s |

Tool 4: Order-of-Magnitude

The power of being “roughly right”

You Already Do This

“Can I drive there before dinner?”

You estimate:

- Distance: ~50 miles

- Speed: ~50 mph

- Time: ~1 hour

No calculator needed. Good enough.

Why It’s Essential in Astronomy

Numbers span 40+ orders of magnitude:

- Nucleus: \(10^{-13}\) cm

- Observable universe: \(10^{28}\) cm

Exact precision can hide the physics.

If you’re off by a factor of 2, that’s a triumph.

If you’re off by \(10^{10}\), something’s wrong.

The “Rule of 3”

When estimating:

- Coefficient \(< 3\) → round down to 1

- Coefficient \(> 3\) → round up to 10

Example:

- \(2 \times 10^{33}\) → \(10^{33}\)

- \(7 \times 10^{10}\) → \(10^{11}\)

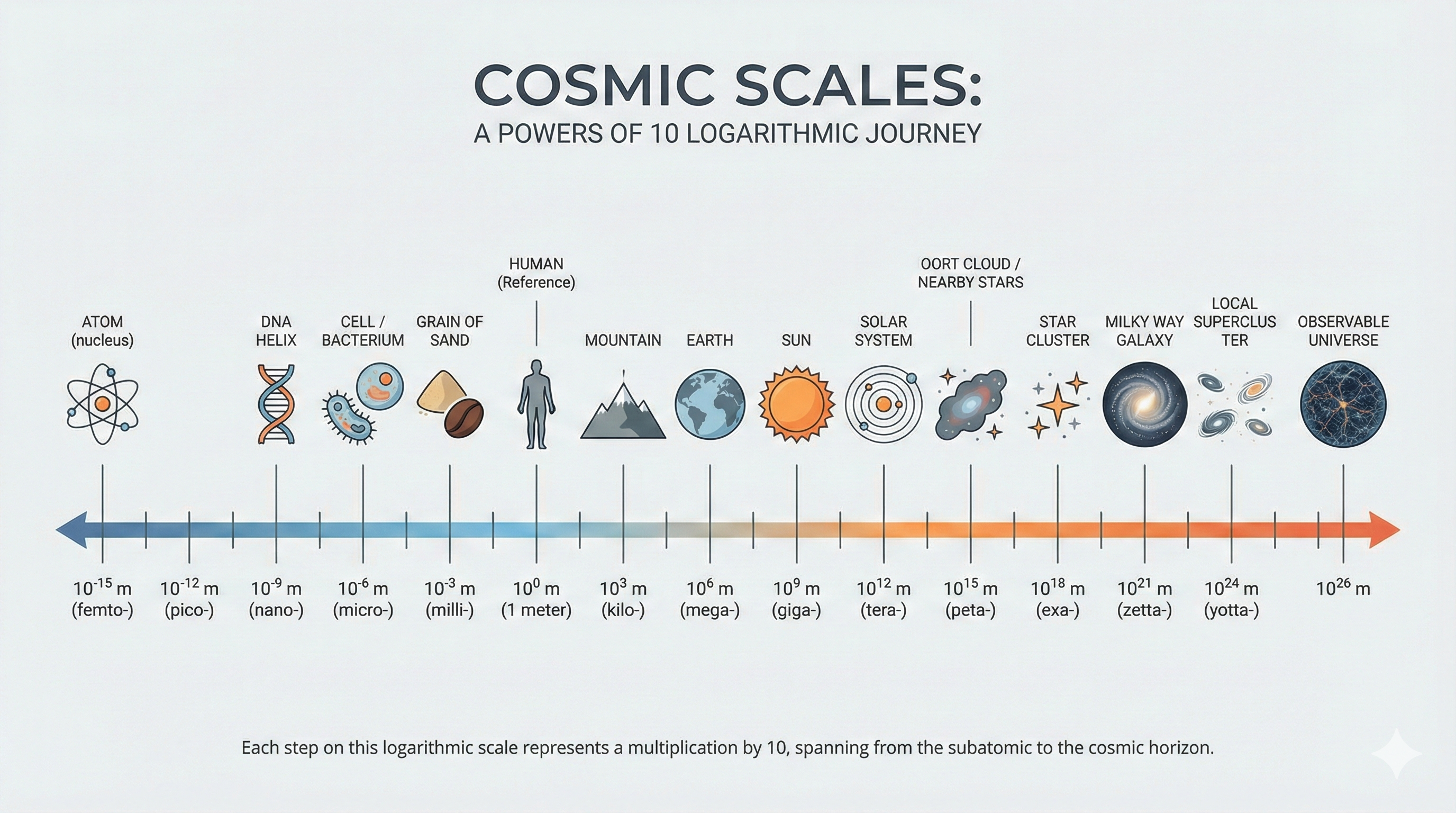

The Universe’s Phone Number

Cosmic Scales: Powers of 10

Reading the Phone Number

Area Code (555): Three steps DOWN from human scale

- × \(10^{-5}\) : human → cells

- × \(10^{-5}\) : cells → atoms

- × \(10^{-5}\) : atoms → nucleus

Exchange (711): Solar system

- × \(10^{7}\) : human → Earth

- × \(10^{1}\) : Earth → Jupiter

- × \(10^{1}\) : Jupiter → Sun

Reading the Phone Number (cont.)

Subscriber (2555): Cosmos

- × \(10^{2}\) : Sun → 1 AU (Earth–Sun distance)

- × \(10^{5}\) : 1 AU → nearest stars (~1 pc)

- × \(10^{5}\) : nearest stars → Milky Way

- × \(10^{5}\) : Milky Way → observable universe

If your calculation gives stellar distance = \(10^{11}\) cm…

That’s Sun-sized, not star-distance. Red flag!

Everyday Example: Piano Tuners in Chicago

How many piano tuners work in Chicago?

- Population: ~3 million → \(10^6\)

- Pianos per household: ~1/20 → \(10^{-1}\)

- Tunings per piano per year: ~1

- Tunings per tuner per year: ~500 → \(10^3\)

\[\frac{10^6 \times 10^{-1} \times 1}{10^3} = 10^2 \approx 100\text{–}300 \text{ tuners}\]

Stop & Solve 4: OOM + Scaling — Black Hole Sizes

Goal

Use a known anchor + scaling to stay in the right powers-of-ten “zip code.”

Assume:

- A 1 \(M_\odot\) black hole has \(R_s \approx 3\,\mathrm{km}\).

- \(R_s\) scales linearly with mass: \(R_s \propto M\).

- Estimate \(R_s\) for a 10 \(M_\odot\) black hole.

- Estimate \(R_s\) for a 4 million \(M_\odot\) black hole (Sgr A* scale).

- Convert #2 to scientific notation (km), then decide: closer to

- Earth size (\(\sim 10^4\) km),

- Sun size (\(\sim 10^6\) km),

- or AU size (\(\sim 10^8\) km)?

Stop & Solve 4 — Solution

Since \(R_s \propto M\):

10 \(M_\odot\): \[R_s \approx 3\,\mathrm{km}\times 10 \approx 30\,\mathrm{km}\]

\(4\times 10^6\,M_\odot\): \[R_s \approx 3\,\mathrm{km}\times 4\times 10^6 \approx 1.2\times 10^7\,\mathrm{km}\]

Comparison: \[1.2\times 10^7\,\mathrm{km}\] is bigger than Sun-scale (\(\sim 10^6\) km) and smaller than AU-scale (\(\sim 10^8\) km) — closer to AU than to the Sun, but still within an order of magnitude of “solar system” scales.

Bonus: Verify the Anchor Value

Where did \(R_s \approx 3\) km come from? Use \(R_s \approx \frac{GM}{c^2}\)

CGS values:

- \(G \approx 10^{-7}\,\frac{\text{cm}^3}{\text{g}\cdot\text{s}^{2}}\)

- \(M_\odot \approx 10^{33}\,\text{g}\)

- \(c \approx 10^{10}\,\frac{\text{cm}}{\text{s}}\)

Substitute: \[R_s \approx \frac{10^{-7} \cdot 10^{33}}{(10^{10})^2}\,\frac{\text{cm}^3 \cdot \cancel{\text{g}} \cdot \cancel{\text{s}^{2}}}{\cancel{\text{g}} \cdot \cancel{\text{s}^{2}} \cdot \text{cm}^2}\]

\[= \frac{10^{26}}{10^{20}}\,\text{cm} = 10^{6}\,\text{cm} = 10\,\text{km}\]

Exact: 3 km. Factor of 3 off — OOM success!

Connecting the Toolkit

The Problem-Solving Flow

Use all four tools together for robust reasoning.

Your New Superpowers

| Tool | Question It Answers |

|---|---|

| Dimensional Analysis | Is this equation physically valid? |

| Ratio Method | How does this compare to something known? |

| Unit Conversions | What’s the numeric value in CGS? |

| OOM Estimation | Does this answer make sense? |

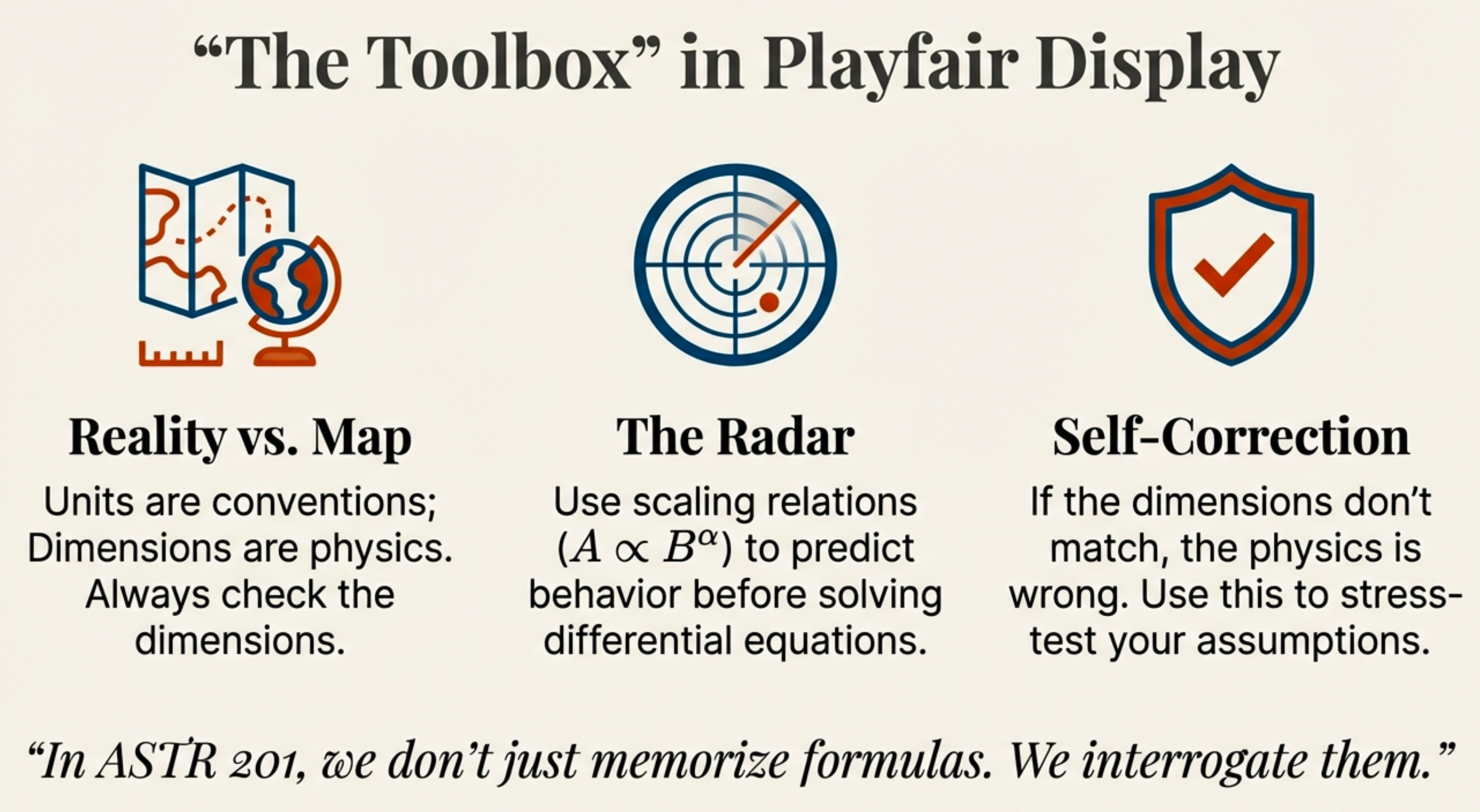

The Toolbox

Preview: Where You’ll Use These

- Module 2: Stellar distances → ratios everywhere

- Module 3: Stellar structure → dimensional scaling

- Module 4: Cosmology → OOM across the universe

These tools are your scientific radar for the rest of the course.

One Thing to Remember

The Takeaway

If you forget everything else from today, remember this:

Dimensions are your smoke detector.

Before trusting any equation, check that both sides have the same dimensions.

If they don’t match, the physics is guaranteed to be wrong.

Questions?

Common questions at this point:

- “What counts as showing work on homework?”

- “How strict are you about units?”

- “Do we need to memorize the phone number?”

Solutions Reference

Detailed step-by-step solutions for self-study

Solution 1: Dimensional Detective — Full Work

Setup

Given: Four candidate formulas for orbital period \(P\)

Find: Which have dimensions of time \([T]\)

Key fact: \([G] = [M^{-1}L^3T^{-2}]\), so \([GM] = [L^3T^{-2}]\)

Option 1: \(P \propto \dfrac{r^2}{GM}\)

\[\left[\frac{r^2}{GM}\right] = \frac{[L]^2}{[L^3T^{-2}]} = \frac{[L^2]}{[L^3][T^{-2}]} = [L^{2-3}][T^{+2}] = [L^{-1}T^2]\]

\[\boxed{\text{Not } [T] \text{ — WRONG}}\]

Solution 1 (cont.) — Options 2–4

Option 2: \(P \propto \sqrt{\dfrac{r^3}{GM}}\)

\[\left[\sqrt{\frac{r^3}{GM}}\right] = \sqrt{\frac{[L^3]}{[L^3T^{-2}]}} = \sqrt{\frac{[L^3]}{[L^3]}\cdot[T^2]} = \sqrt{[T^2]} = [T] \quad \boxed{\checkmark \text{ CORRECT}}\]

Option 3: \(P \propto \dfrac{r}{\sqrt{GM}}\)

\[\left[\frac{r}{\sqrt{GM}}\right] = \frac{[L]}{\sqrt{[L^3T^{-2}]}} = \frac{[L]}{[L^{3/2}T^{-1}]} = [L^{1-3/2}][T^1] = [L^{-1/2}T] \quad \boxed{\text{WRONG}}\]

Option 4: \(P \propto \sqrt{\dfrac{GM}{r^3}}\)

\[\left[\sqrt{\frac{GM}{r^3}}\right] = \sqrt{\frac{[L^3T^{-2}]}{[L^3]}} = \sqrt{[T^{-2}]} = [T^{-1}] \quad \boxed{\text{WRONG (frequency, not period)}}\]

Solution 2: Mars Year — Full Work

Setup

Given: Mars orbital distance \(a = 1.52\) AU Find: Mars orbital period \(P\) in years Formula: \(\left(\dfrac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\dfrac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\) (Kepler’s Third Law)

Step 1: Substitute known value \[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = (1.52)^3\]

Step 2: Evaluate the cube (show your work!) \[1.52^3 = 1.52 \times 1.52 \times 1.52 = 2.31 \times 1.52 \approx 3.51\]

Step 3: Take square root of both sides \[\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}} = \sqrt{3.51} \approx 1.87\]

Step 4: Solve for \(P\) \[\boxed{P_{\text{Mars}} \approx 1.9 \text{ years}}\]

Actual value: 1.88 years — excellent agreement!

Solution 2 (cont.) — Why \(P \propto a^{3/2}\)?

Physical interpretation:

A planet farther from the Sun experiences two effects:

- Longer path: Circumference \(\propto a\), so more distance to travel

- Weaker gravity: Force \(\propto 1/a^2\), so slower orbital speed

Combined effect: \(P \propto a^{3/2}\) — period grows faster than linearly with distance.

Sanity check

- Earth at 1 AU: \(P = 1\) yr ✓

- Mars at 1.52 AU: \(P \approx 1.9\) yr ✓ (farther → longer)

- Jupiter at 5.2 AU: \(P = 5.2^{1.5} \approx 12\) yr ✓

Solution 3A: Speed Conversion — Full Work

Setup

Given: Earth’s orbital speed = \(30\) km/s Find: Speed in cm/s (CGS) Method: Multiply by conversion factors = 1

Step 1: Write conversion factors \[1\,\text{km} = 10^3\,\text{m} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \frac{10^3\,\text{m}}{1\,\text{km}} = 1\] \[1\,\text{m} = 10^2\,\text{cm} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \frac{10^2\,\text{cm}}{1\,\text{m}} = 1\]

Step 2: Chain the conversions (watch units cancel!) \[30\,\frac{\cancel{\text{km}}}{\text{s}} \times \frac{10^3\,\cancel{\text{m}}}{1\,\cancel{\text{km}}} \times \frac{10^2\,\text{cm}}{1\,\cancel{\text{m}}} = 30 \times 10^3 \times 10^2 \,\frac{\text{cm}}{\text{s}}\]

Step 3: Combine powers of 10 \[= 30 \times 10^{3+2}\,\text{cm/s} = 30 \times 10^5\,\text{cm/s} = \boxed{3 \times 10^6\,\text{cm/s}}\]

Solution 3B: Luminosity Conversion — Full Work

Setup

Given: \(L_\odot = 3.8 \times 10^{26}\) W (SI) Find: \(L_\odot\) in erg/s (CGS) Key conversion: \(1\,\text{W} = 1\,\text{J/s}\) and \(1\,\text{J} = 10^7\,\text{erg}\)

Step 1: Expand Watts to fundamental units \[3.8 \times 10^{26}\,\text{W} = 3.8 \times 10^{26}\,\frac{\text{J}}{\text{s}}\]

Step 2: Convert Joules to ergs \[= 3.8 \times 10^{26}\,\frac{\cancel{\text{J}}}{\text{s}} \times \frac{10^7\,\text{erg}}{1\,\cancel{\text{J}}}\]

Step 3: Combine powers of 10 \[= 3.8 \times 10^{26} \times 10^7\,\frac{\text{erg}}{\text{s}} = 3.8 \times 10^{26+7}\,\text{erg/s}\]

\[\boxed{L_\odot = 3.8 \times 10^{33}\,\text{erg/s}}\]

Common error: Forgetting that 1 J = \(10^7\) erg (not \(10^3\)!). Energy in CGS uses small units.

Solution 4: Black Hole Scaling — Full Work

Setup

Given: \(R_s(1\,M_\odot) \approx 3\) km (anchor value) Scaling law: \(R_s \propto M\) (linear) Find: \(R_s\) for 10 \(M_\odot\) and \(4 \times 10^6\,M_\odot\)

Part 1: Stellar-mass black hole (10 \(M_\odot\)) \[\frac{R_s(10\,M_\odot)}{R_s(1\,M_\odot)} = \frac{10\,M_\odot}{1\,M_\odot} = 10\]

\[R_s(10\,M_\odot) = 10 \times 3\,\text{km} = \boxed{30\,\text{km}}\]

Part 2: Supermassive black hole (\(4 \times 10^6\,M_\odot\), like Sgr A*) \[\frac{R_s(4\times10^6\,M_\odot)}{R_s(1\,M_\odot)} = \frac{4\times10^6\,M_\odot}{1\,M_\odot} = 4\times10^6\]

\[R_s = (4\times10^6) \times 3\,\text{km} = 12\times10^6\,\text{km} = \boxed{1.2\times10^7\,\text{km}}\]

Solution 4 (cont.) — Scale Comparison

Part 3: How big is \(1.2 \times 10^7\) km?

| Object | Size |

|---|---|

| Earth radius | \(6.4 \times 10^3\) km |

| Sun radius | \(7 \times 10^5\) km |

| Sgr A* horizon | \(1.2 \times 10^7\) km |

| Mercury’s orbit | \(5.8 \times 10^7\) km |

| 1 AU | \(1.5 \times 10^8\) km |

\[\boxed{\text{Sgr A* is about 17× the Sun's radius, or } \sim 0.08 \text{ AU}}\]

Sanity check

- Bigger than Sun? ✓ (by factor ~17)

- Smaller than 1 AU? ✓ (by factor ~12)

- Sgr A’s horizon (~0.08 AU) fits well inside* Mercury’s orbit (~0.39 AU)

Problem-Solving Best Practices

The Template

Every solution should follow this structure:

- Setup box: State what’s given and what you’re finding

- Write the formula: Include units/dimensions

- Substitute: Put numbers in, keep units attached

- Cancel units: Cross out matching units explicitly

- Compute: Show exponent arithmetic (\(10^a \times 10^b = 10^{a+b}\))

- Box the answer: With units!

- Sanity check: Does the answer make physical sense?

Common pitfalls

- Dropping units mid-calculation

- Forgetting to square/cube conversion factors

- Not checking if answer is in the right “ballpark”

Reference Tables

See the Lecture 2 Reference Handout for:

- CGS unit conversions

- Fundamental physical constants

- Solar units (\(M_\odot\), \(R_\odot\), \(L_\odot\))

- Key distance scales (AU, pc)

- Dimensional “recipes”

ASTR 201 • Lecture 2

![Diagram showing compressed electrons in white dwarf. Explains that density is so high electrons are squeezed, quantum mechanics (ℏ) and electron mass (m_e) take over, temperature becomes irrelevant. Matching dimensions for pressure [M][L]^-1[T]^-2 using ℏ, m_e, and number density n gives P_deg ∝ ℏ²n^(5/3)/m_e.](../../../assets/images/module-01/case-C-white-dwarf-dimensional-analysis-nblm-1.png)