Lecture 4 (Day 1):

Light as Information

Spectrum • Photons • Interactions • Temperature

February 3, 2026

Learning Objectives

By the end of today, you will be able to:

- Relate wavelength (\(\lambda\)), frequency (\(\nu\)), and photon energy (\(E\))

- Explain why the visible band is a tiny slice of the EM spectrum

- Describe the main ways light interacts with matter (absorb, emit, transmit, reflect/refract, scatter)

- Use Wien’s law to estimate temperature from a thermal spectrum’s peak

How can a rainbow tell you a star’s temperature?

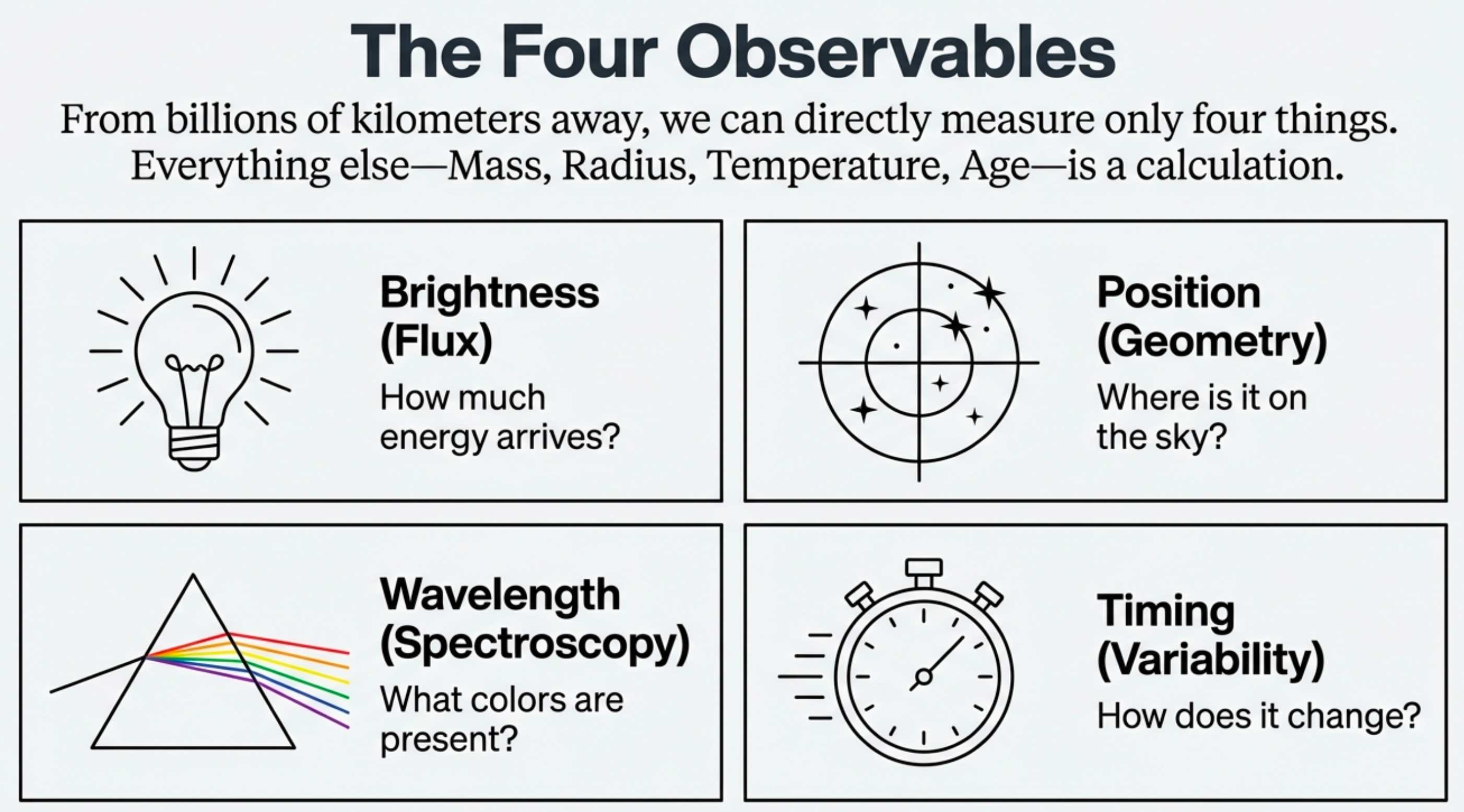

The Course Throughline

Today’s Piece

Measure → Infer → Balance → Evolve

- Measure: intensity vs wavelength (a spectrum)

- Infer: temperature (soon: composition)

A “Pretty Picture” Is Still Data

Brightness patterns + color patterns = physics patterns.

Today’s Game Plan

We’re building inference tool #1:

- What light is (spectrum)

- How light carries energy (photons)

- How matter changes light (interactions)

- How color encodes temperature (blackbody + Wien)

End: quick demos (if time) to lock the intuition.

The Wave Relation

The symbol \(c\) is the speed of light in vacuum.

\[ c = \lambda \nu \tag{1}\]

- In vacuum, \(c \approx 3\times10^{10}\ \mathrm{cm/s}\)

- Solve for wavelength: \(\lambda = c/\nu \;\Rightarrow\; \lambda \propto \nu^{-1}\)

- Solve for frequency: \(\nu = c/\lambda \;\Rightarrow\; \nu \propto \lambda^{-1}\)

- Negative exponents are a compact way to show “inverse” relationships; you can also write \(\lambda \propto 1/\nu\) or \(\nu \propto 1/\lambda\)

Part 1: The Electromagnetic Spectrum

What kind of “messenger” is light?

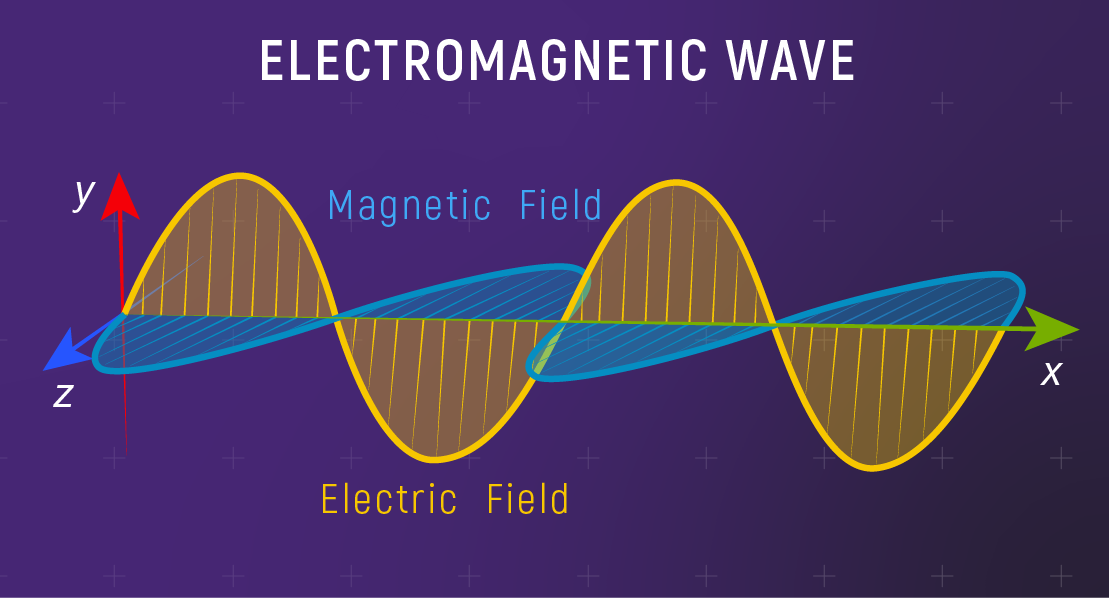

What Is Light?

Wave Picture

Light is an electromagnetic wave.

Three related quantities:

- wavelength \(\lambda\) (distance between crests)

- frequency \(\nu\) (cycles per second)

- speed \(c\) (in vacuum)

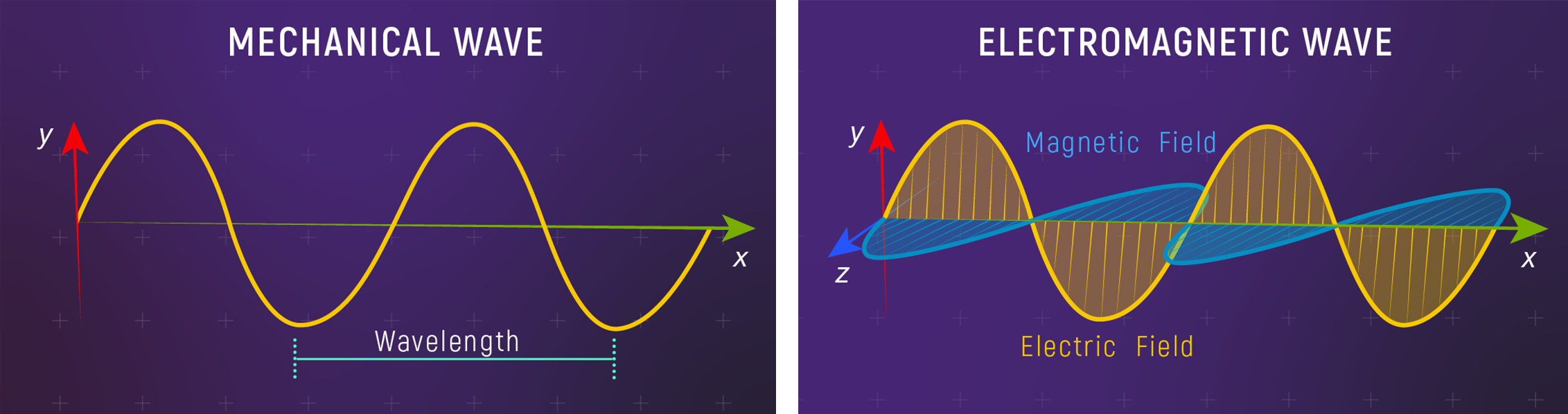

Mechanical Waves vs EM Waves

Mechanical waves need a medium.

EM waves don’t — that’s why light crosses the vacuum of space.

The Wave Relation

The symbol \(c\) is the speed of light in vacuum.

\[ c = \lambda \nu \tag{2}\]

- In vacuum, \(c \approx 3\times10^{10}\ \mathrm{cm/s}\)

- Solve for wavelength: \(\lambda = c/\nu \;\Rightarrow\; \lambda \propto \nu^{-1}\)

- Solve for frequency: \(\nu = c/\lambda \;\Rightarrow\; \nu \propto \lambda^{-1}\)

- Negative exponents are a compact way to show “inverse” relationships; you can also write \(\lambda \propto 1/\nu\) or \(\nu \propto 1/\lambda\)

Units Sanity Check

Fast

If \(c = \lambda\nu\), then the units must satisfy:

\[[\mathrm{cm/s}] = [\mathrm{cm}]\,[\mathrm{s^{-1}}]\]

If the units don’t match, the physics can’t be right.

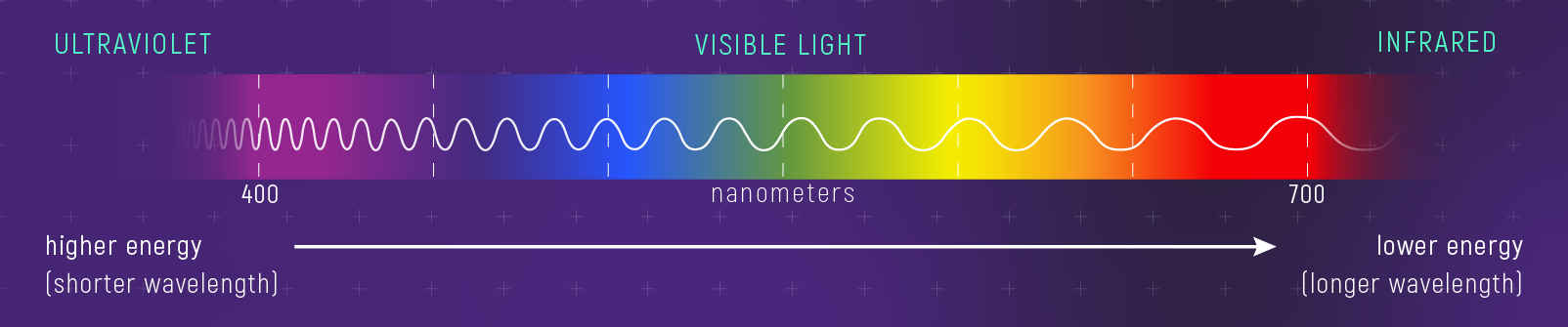

Wavelength Units

So We Speak the Same Language

Visible light is roughly:

- \(400\)–\(700\ \mathrm{nm}\)

Conversion: \(1\ \mathrm{nm}=10^{-7}\ \mathrm{cm}\).

Course convention: CGS (cm, s, erg, K).

Energy unit: \(1\ \mathrm{erg} = 1\ \mathrm{g\cdot cm^2/s^2}\).

🧠 Predict: No Calculator

If the wavelength doubles, the frequency…

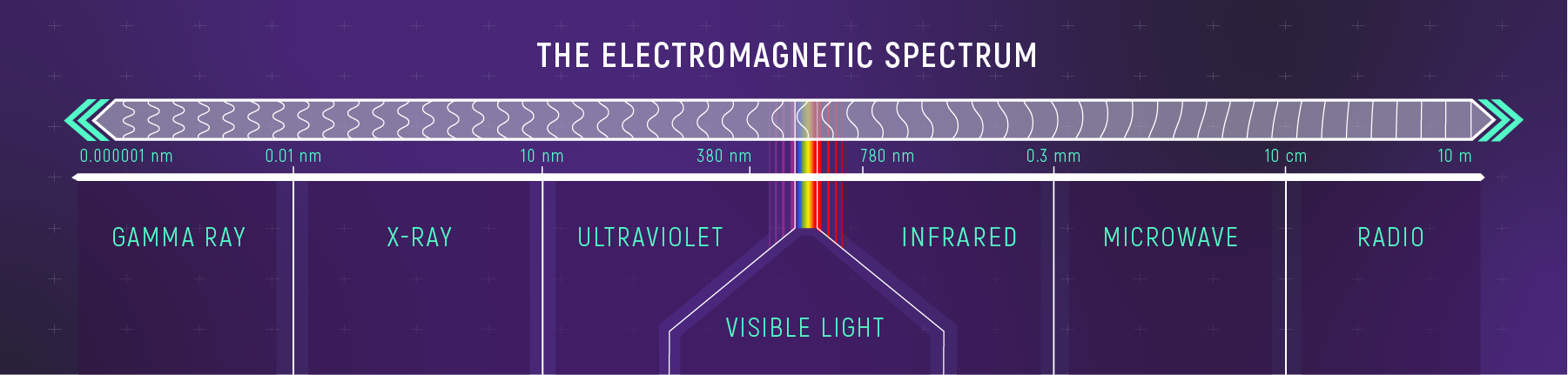

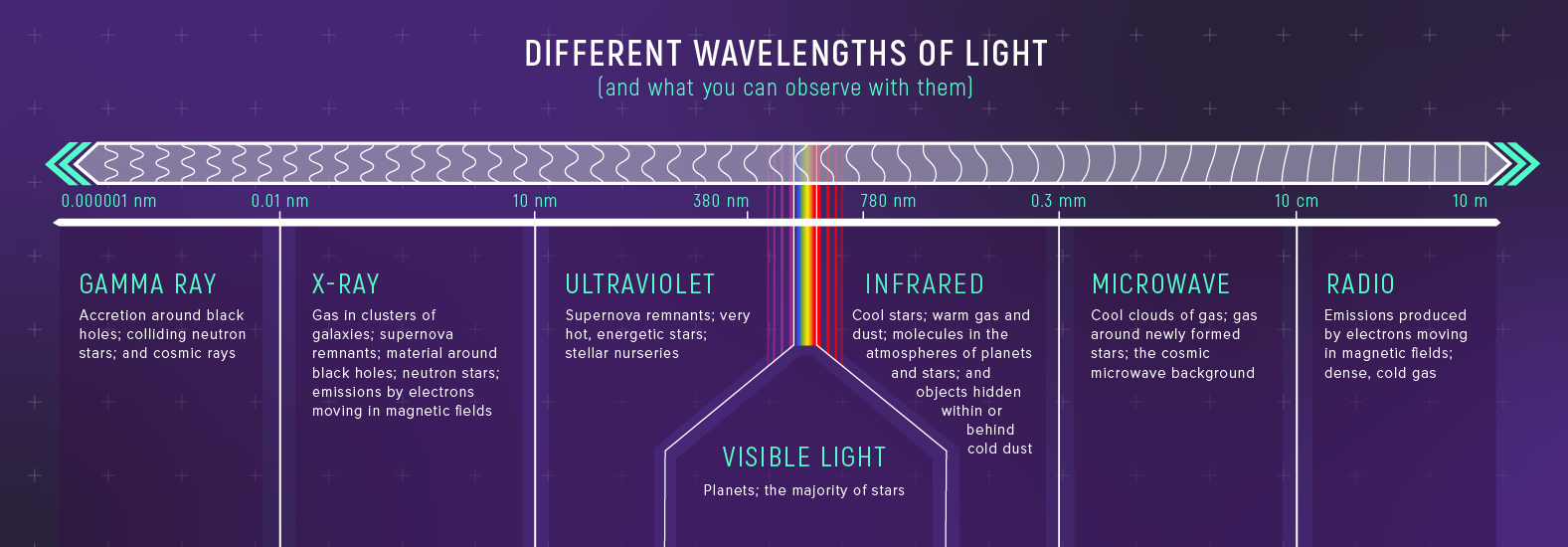

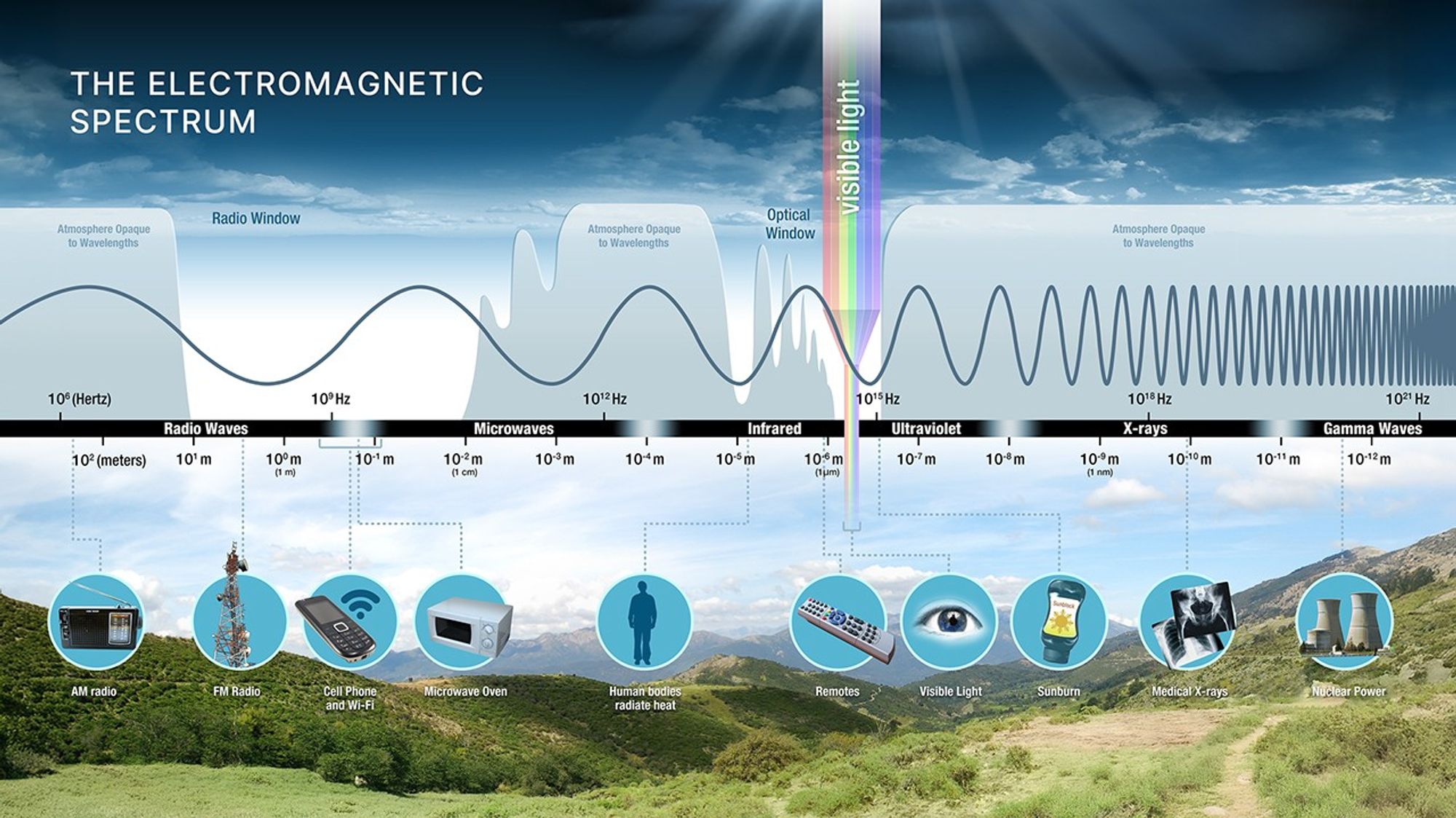

The Electromagnetic Spectrum

Visible light is a tiny slice.

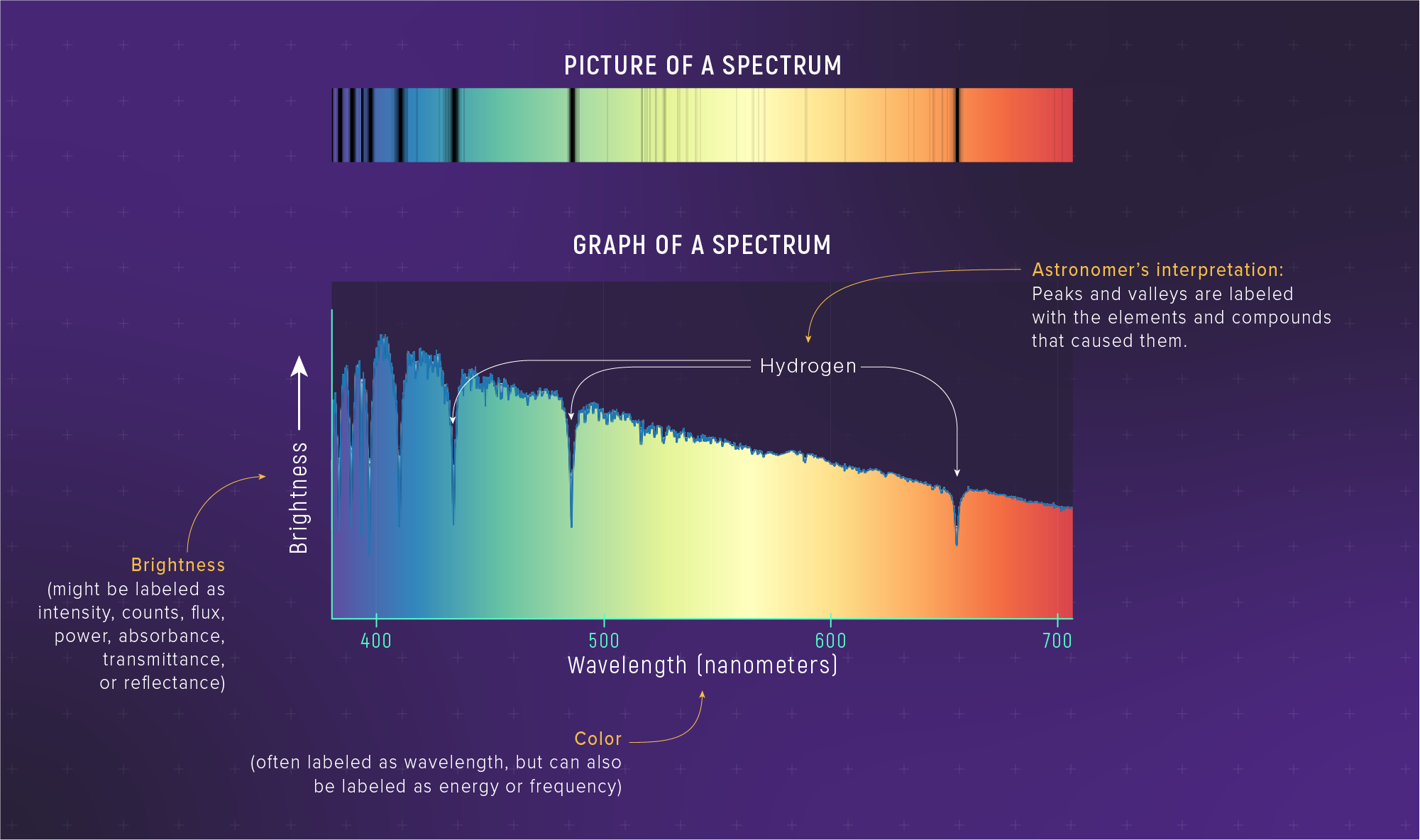

A Spectrum Is a Measurement

A spectrum is:

brightness as a function of wavelength

That’s more informative than a single “brightness number”.

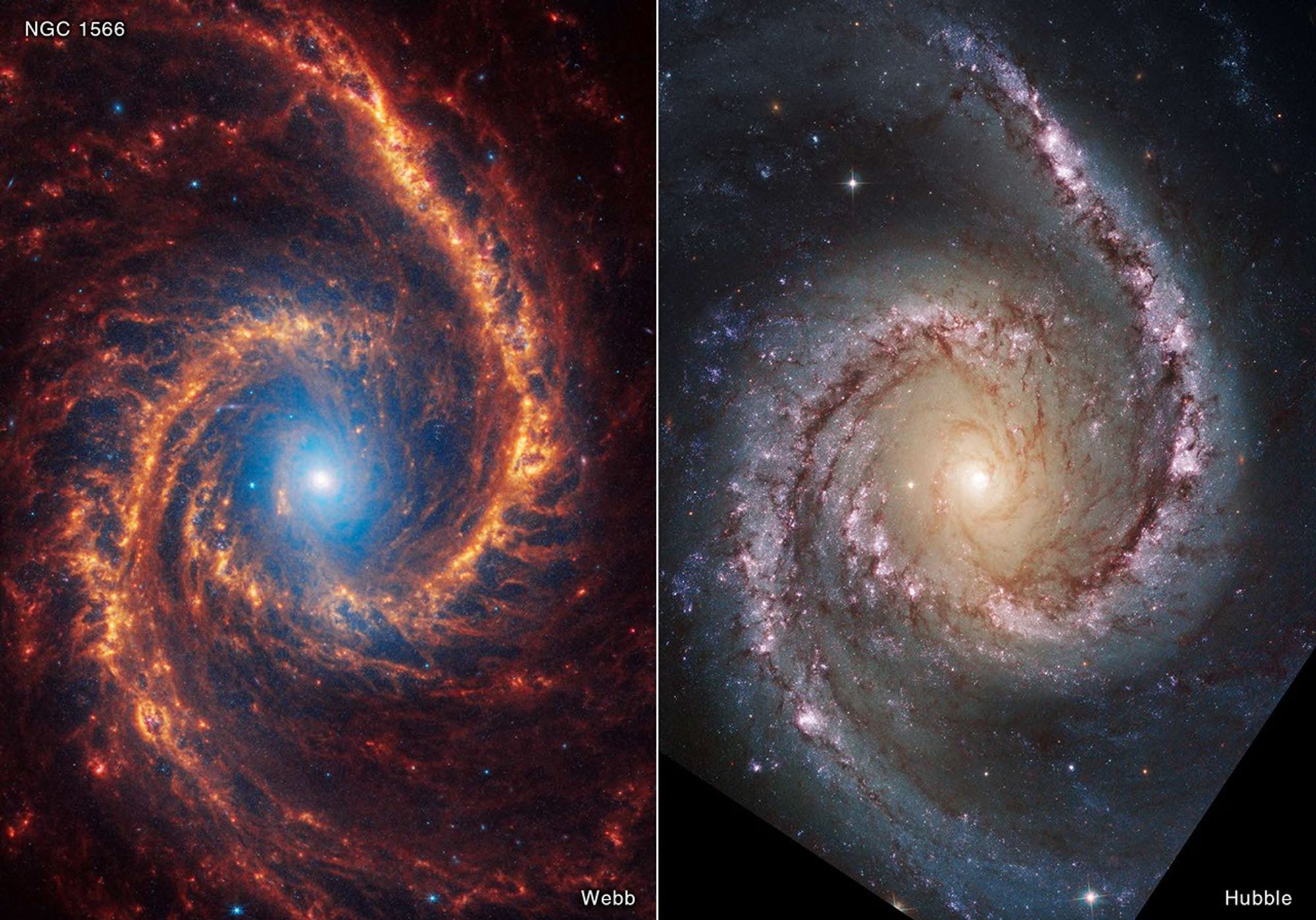

The Spectrum Reveals Different Physics

Same Universe — Different Physics

Different wavelengths highlight different components (stars, dust, gas).

🧠 Think–Pair–Share

30–60 s

Which wavelength band is best for seeing into dusty star-forming regions?

- Visible

- Ultraviolet

- Infrared

Answer: Infrared — longer wavelengths pass through dust more easily.

Part 2: Photons and Energy

Light is also made of particles.

Photon Energy

\[ E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1} \tag{3}\]

What this equation is saying:

- Direct: \(E \propto \nu\)

- Inverse: \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\) (same as \(E \propto 1/\lambda\))

- shorter \(\lambda\) → larger \(E\)

- longer \(\lambda\) → smaller \(E\)

Here \(h\) is Planck’s constant (\(6.63\times10^{-27}\ \mathrm{erg\cdot s}\)).

Units check: (erg·s)·(s\(^{-1}\)) = erg.

Wave–Particle Duality

Optional but Helpful

Sometimes light behaves like a wave.

Sometimes it behaves like particles (photons).

Which model is useful depends on what you measure.

Spoiler Alert

For Later: Matter Waves

It’s not just light.

- particles also have wave behavior

- the “matter wavelength” gets shorter when momentum gets bigger

- \(p\) is momentum (in CGS: \(\mathrm{g\cdot cm/s}\))

- \(h\) is Planck’s constant (\(6.63\times10^{-27}\ \mathrm{erg\cdot s}\))

Teaser: \(\lambda = \frac{h}{p}\) (we’ll use this when we talk about stars in Module 2). This is a quantum-mechanics result linked to the Heisenberg uncertainty principle.

🧠 Predict: Which Photon Is More Energetic?

Which photon has higher energy?

🧠 Predict: Scaling

If wavelength is cut in half, photon energy…

Why Astronomers Care About Photon Energy

High-energy photons (UV/X-ray/gamma) can:

- ionize atoms

- heat million-degree plasma

- reveal extreme environments (accretion, explosions)

Low-energy photons (IR/radio) can:

- pass through dust

- trace cold gas and molecules

Part 3: How Light Interacts with Matter

Light carries information because matter “filters” it.

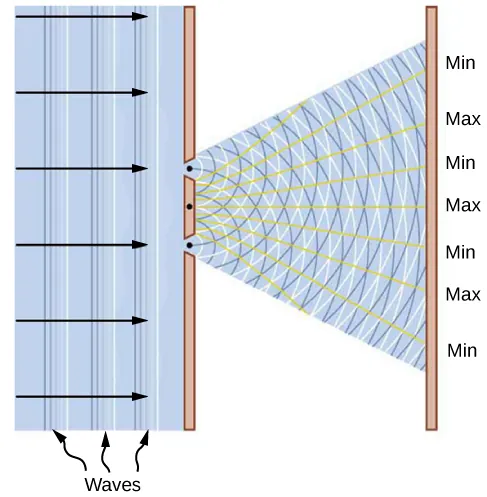

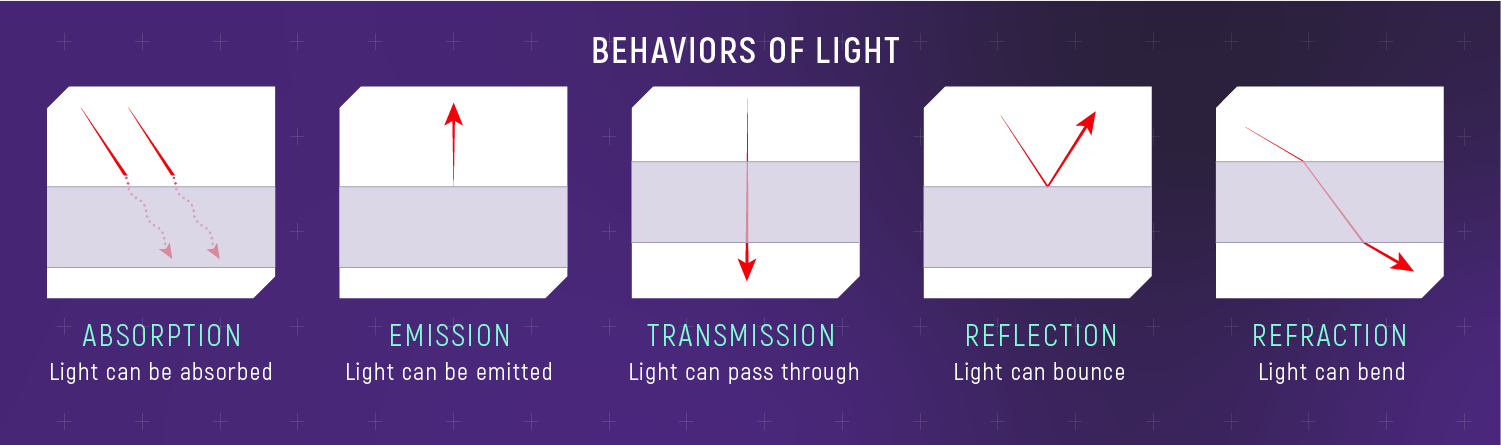

Five Outcomes Plus Scattering

When light hits matter, it can be:

- transmitted

- absorbed

- emitted

- reflected / refracted

- scattered

Absorption and Emission

Tiny Preview

Absorption/emission are how light becomes a chemical fingerprint.

Next class: spectral lines tell us what a star is made of.

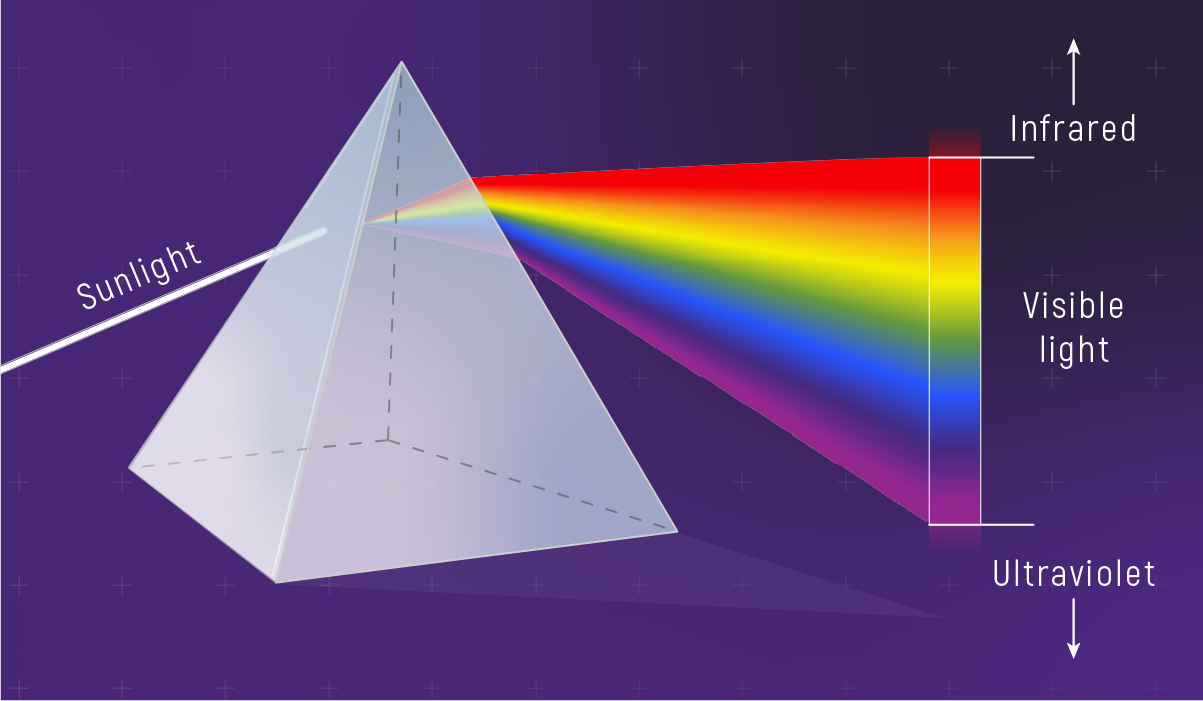

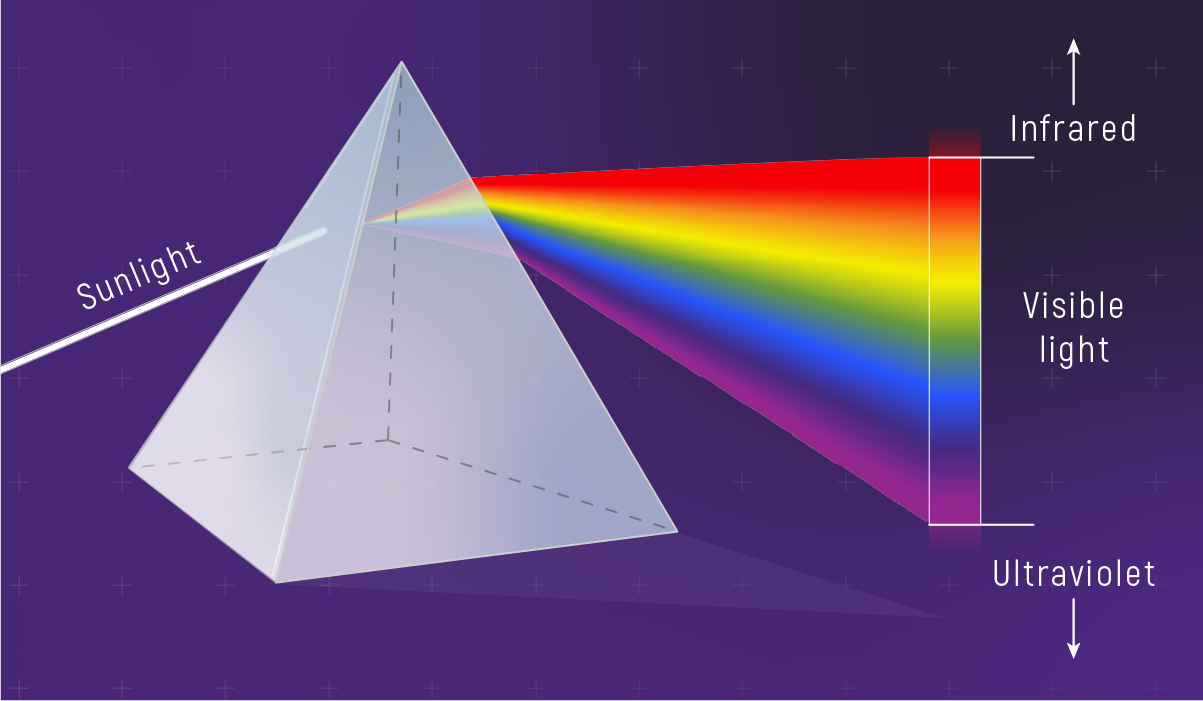

Refraction and Dispersion

Preview

In glass, different wavelengths bend by different amounts.

That’s why prisms “spread out” white light.

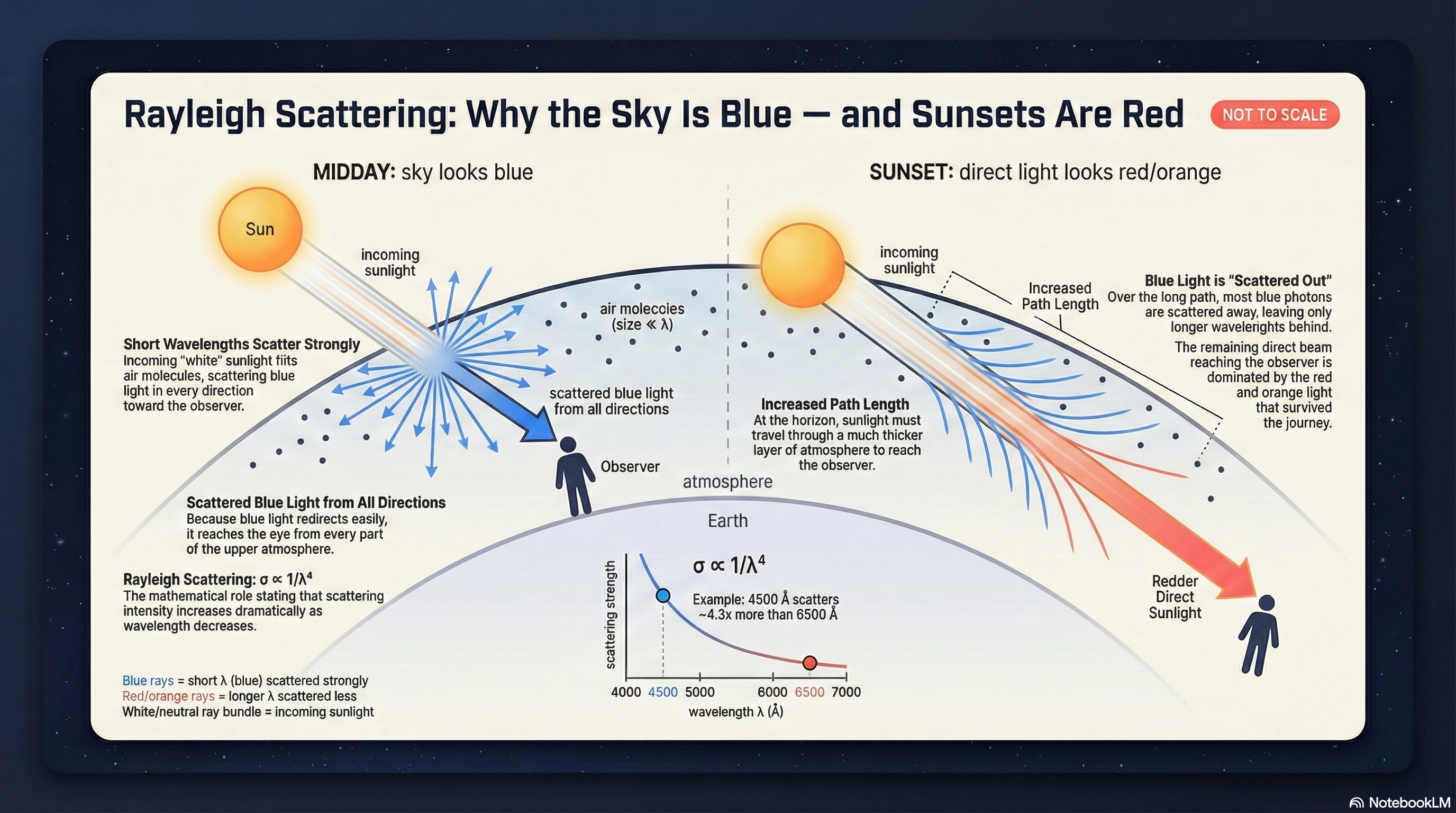

Scattering: Why the Sky Is Blue

For very small particles (like air molecules):

\[\text{scattering} \propto \lambda^{-4}\]

Shorter wavelength scatters much more.

Valid when particle size \(\ll \lambda\) (molecules).

🧠 Predict: How Steep Is \(\lambda^{-4}\)?

If wavelength is cut in half, Rayleigh scattering becomes…

🧠 Predict: Rayleigh

On a planet with a similar atmosphere, which light scatters more?

The Atmosphere Is a Filter

Earth’s atmosphere is not transparent everywhere.

- Optical window (good)

- Radio window (good)

- Some infrared gets through in atmospheric windows, but many bands are absorbed by molecules (H\(_2\)O, CO\(_2\), CH\(_4\), O\(_3\)).

- Most UV/X-ray/gamma blocked

Opacity Preview: “How Far Light Gets”

Matter can be transparent or opaque depending on wavelength.

- dust blocks visible more than infrared

- Earth’s atmosphere blocks most UV/X-ray

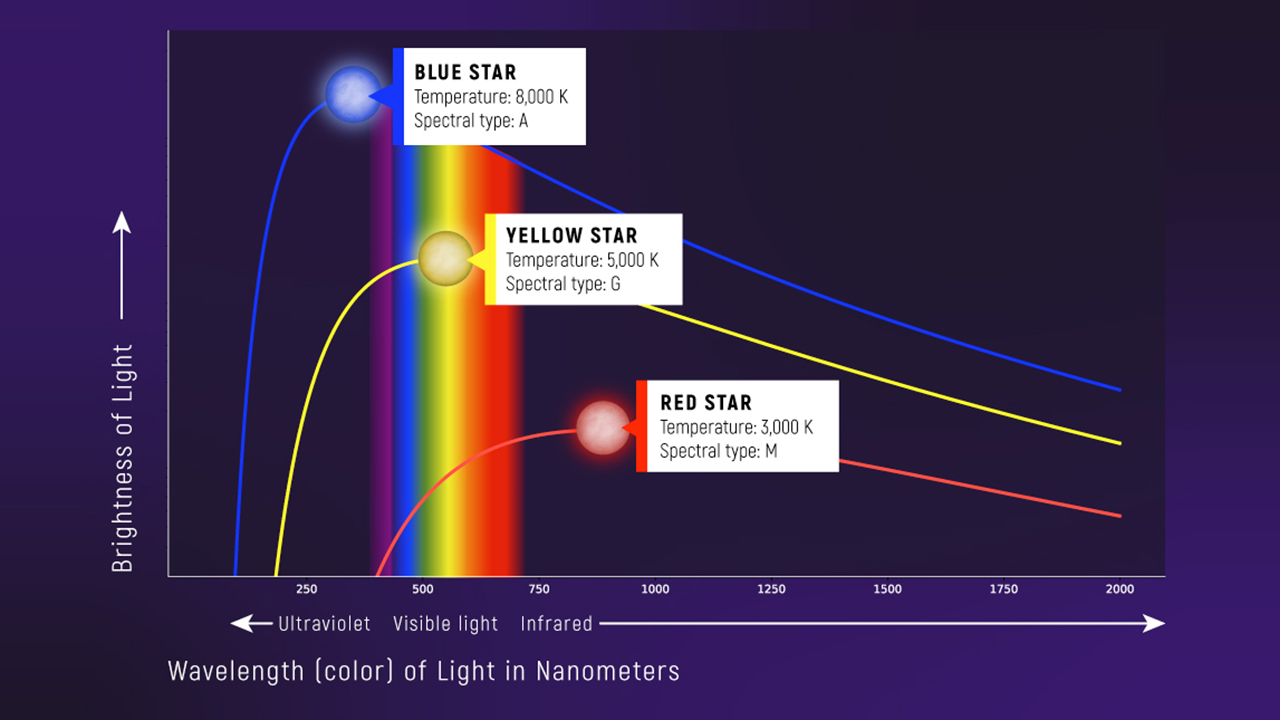

Part 4: Thermal Radiation (Blackbodies)

Color encodes temperature.

The Blackbody Idea

A blackbody is an ideal thermal emitter:

- spectrum shape depends mainly on temperature

- hotter objects emit more light and peak at shorter wavelength

Why “Black”body?

An ideal blackbody:

- absorbs all wavelengths well (“black”)

- therefore emits thermal radiation efficiently

Why Stars Are Approximately Blackbodies

Stars have a dense “surface” (the photosphere) where:

- photons interact many times with matter

- the radiation field becomes close to thermal

But atmospheres add spectral lines — next class we explain why.

Two Things Change When \(T\) Changes

When temperature increases:

- the peak shifts to shorter wavelength (Wien)

- the total emitted light increases (area under the curve)

The Key Pattern

Look, Don’t Memorize

Hotter → peak shifts left (bluer) and the whole curve gets taller.

Wien’s Law

Inference Tool #1

The peak wavelength of a thermal spectrum tells temperature:

\[ \lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1} \tag{4}\]

Wien constant: \(b \approx 0.2898\ \mathrm{cm\cdot K}\)

- \(\lambda_{\mathrm{peak}}\) shorter → \(T\) higher

- \(\lambda_{\mathrm{peak}}\) longer → \(T\) lower

Units Check

Wien’s Law

If \(\lambda_{\mathrm{peak}} = bT^{-1}\), then \(b\) must have units of:

\[[\text{length}]\cdot[\text{temperature}]\]

🧠 Predict: Scaling

If temperature doubles, the peak wavelength becomes…

🧠 Predict: No Numbers

A star with a shorter peak wavelength is…

Worked Example: The Sun

Fast

Take \(\lambda_{\mathrm{peak}} \approx 500\ \mathrm{nm} = 5\times10^{-5}\ \mathrm{cm}\).

. . .

Use \(b \approx 0.29\ \mathrm{cm\cdot K}\):

\[T \approx 0.29\cdot(5\times10^{-5})^{-1} \approx 5.8\times10^{3}\ \mathrm{K}\]

Stop & Solve: Compare Two Peaks

Star A peaks at \(500\ \mathrm{nm}\).

Star B peaks at \(1000\ \mathrm{nm}\).

How do their temperatures compare?

Stop & Solve — Solution

Because \(\lambda_{\mathrm{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\):

\[\frac{T_B}{T_A} = \frac{\lambda_A}{\lambda_B} = \frac{500\ \mathrm{nm}}{1000\ \mathrm{nm}} = \frac{1}{2}\]

Units cancel in the ratio, so the temperature ratio is dimensionless.

Star B is half the temperature of Star A.

Worked Example: A Cool Star

Fast

Suppose \(T \approx 3500\ \mathrm{K}\) (a cool red supergiant).

\[\lambda_{\mathrm{peak}} \approx 0.29\cdot(3500)^{-1}\ \mathrm{cm}\approx 8.3\times10^{-5}\ \mathrm{cm}\approx 830\ \mathrm{nm}\]

That’s just beyond visible red → near infrared.

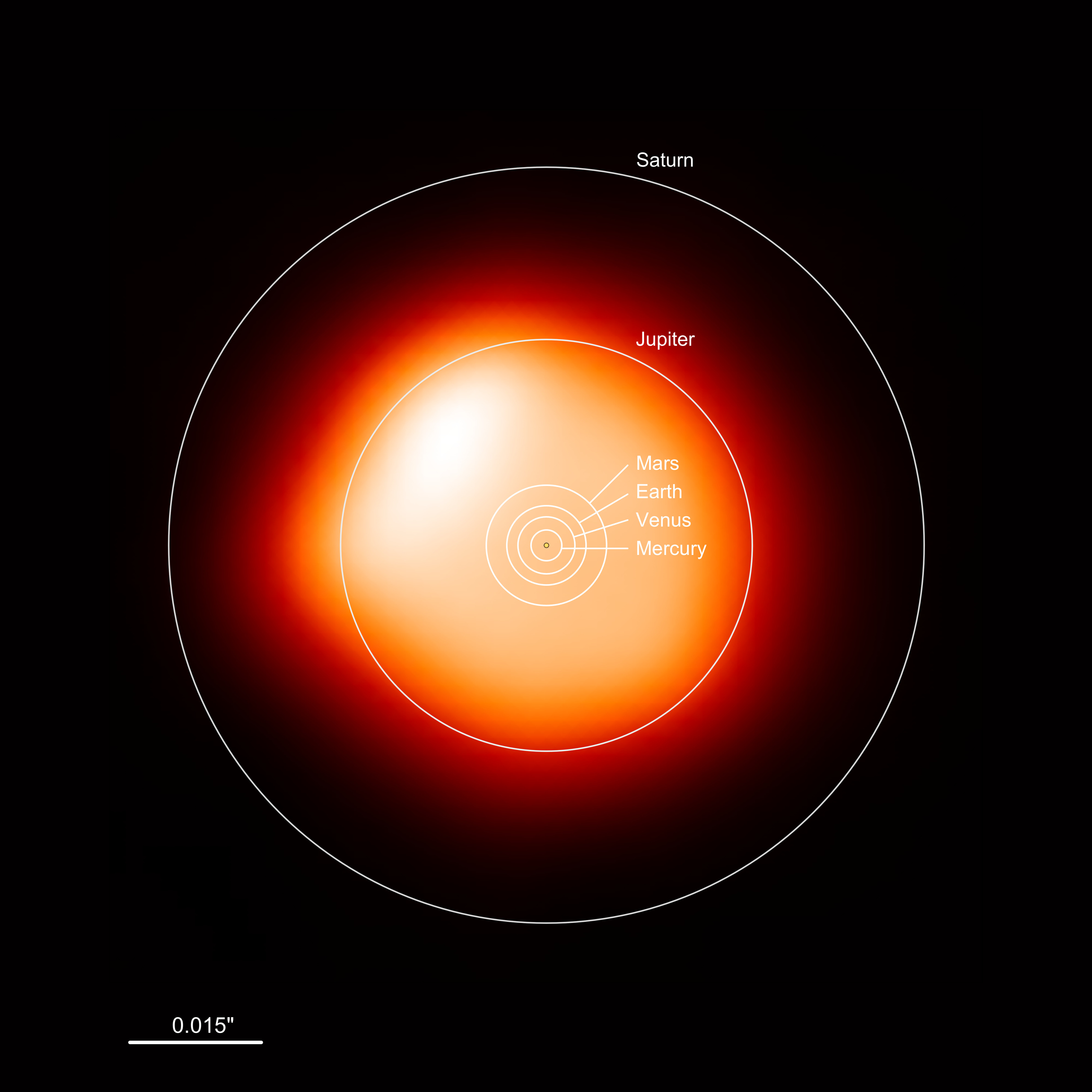

“Big Star” Context

Optional Wow

Betelgeuse is an example.

A Common Misconception

“If a star peaks in the UV, it emits only UV.”

No — a hot blackbody emits across many wavelengths.

Next Class

Day 2: Continuum + Lines

Blackbody is the starting model.

Next class we add:

- absorption lines → composition

- (later) Doppler shifts → motion

Synthesis

Day 1

Today we built the chain:

- Measure: spectrum (intensity vs wavelength)

- Model: blackbody thermal emission

- Infer: temperature (via Wien’s law)

Next class: the fine structure (spectral lines) → composition.

Demo Time

If Time: EM Spectrum

Demo: em-spectrum

Prompt: Where is “visible” on a log scale? What changes fastest: \(\lambda\), \(\nu\), or \(E\)?

Demo Time

If Time: Blackbody Radiation

Demo: blackbody-radiation

Prompt: As \(T\) increases, what happens to (1) peak wavelength and (2) total emitted light?

Exit Ticket

30 seconds

Write one sentence:

“A spectrum is useful because…”

Study Snapshot

Write This Down

- \(c=\lambda\nu\) (wave relation)

- \(E=hc\lambda^{-1}\) (shorter \(\lambda\) → higher energy)

- \(\lambda_{\rm peak}=bT^{-1}\) (shorter peak → hotter)

- \(E \propto \nu\) and \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\)

- \(\lambda_{\rm peak} \propto T^{-1}\)

ASTR 201 • Dr. Anna Rosen • Lecture 4 (Day 1)