flowchart LR O["🔭 Observable\nWhat we measure"] M["📐 Model\nWhat we assume"] I["💡 Inference\nWhat we derive"] O --> M --> I style O fill:#dbeafe,stroke:#2563eb style M fill:#fef3c7,stroke:#d97706 style I fill:#dcfce7,stroke:#16a34a

Lecture 1: Distance & Parallax

How far? The foundation of stellar astrophysics

February 12, 2026

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture, you will be able to:

- Define angular measure (degrees, arcminutes, arcseconds, radians) and convert between them

- Derive and apply the small-angle approximation to relate angular size, true size, and distance

- Define parallax angle and the parsec; calculate distances from parallax measurements

- Derive the inverse-square law (geometric + dimensional analysis approaches)

- Apply \(F = L/(4\pi d^2)\) to infer luminosity from flux and parallax distance

Are all stars like our Sun?

The Problem: Points of Light

Quick Check 1: Are Stars Like Our Sun?

Two stars appear equally bright in your telescope. What can you conclude?

A. They have the same luminosity

B. They are at the same distance

C. You can’t tell — brightness depends on both luminosity and distance

D. The brighter-looking one must be closer

The Degeneracy Problem

Equal apparent brightness can mean:

Scenario 1: A luminous star far away

\[F = \frac{L_{\text{high}}}{4\pi d_{\text{far}}^2}\]

Scenario 2: A dim star nearby

\[F = \frac{L_{\text{low}}}{4\pi d_{\text{near}}^2}\]

The same flux \(F\) — completely different stars. Without distance, you’re stuck.

Distance Is the Master Key

\[\text{Parallax} \xrightarrow{d = 1/p} \text{Distance} \xrightarrow{d + F} \text{Luminosity} \xrightarrow{L + T} \text{HR Diagram}\]

- Distance + apparent brightness = luminosity (today)

- Luminosity + temperature = radius (Lecture 2)

- Distance + spectrum = composition (Lecture 3)

- Distance + radial velocity = mass (Lecture 4)

Everything starts with distance.

The Observable → Model → Inference Framework

| Step | This lecture |

|---|---|

| Observable | Position shifts, brightness |

| Model | Parallax geometry, ISL |

| Inference | Distance, luminosity |

Good scientists always ask: what am I assuming, and what would break it?

Angular Measure

The language of the sky

Degrees, Arcminutes, Arcseconds

| Unit | Size |

|---|---|

| \(1^\circ\) | Full Moon width |

| \(1'\) (arcmin) | \(1/60\) of a degree |

| \(1''\) (arcsec) | \(1/3600\) of a degree |

Stellar parallax happens at the arcsecond scale — tiny shifts against distant background stars.

Radians — The Natural Unit

Definition: 1 radian is the angle subtended by an arc whose length equals the radius.

\[1 \text{ radian} = \frac{360^\circ}{2\pi} \approx 57.3^\circ\]

Radians are dimensionless: angle = arc length / radius = length / length.

Physics formulas like \(\sin\theta \approx \theta\) and \(v = r\omega\) only work in radians.

The Key Conversion: Arcseconds ↔︎ Radians

\[1 \text{ radian} = \frac{360 \times 3600''}{2\pi} \approx 206{,}265''\]

Inverted (the form you’ll use most):

\[\boxed{1'' = \frac{1}{206{,}265} \text{ rad} \approx 4.85 \times 10^{-6} \text{ rad}}\]

Memorize 206,265. It appears in every parallax calculation.

The Small-Angle Approximation

Connecting angular size, true size, and distance

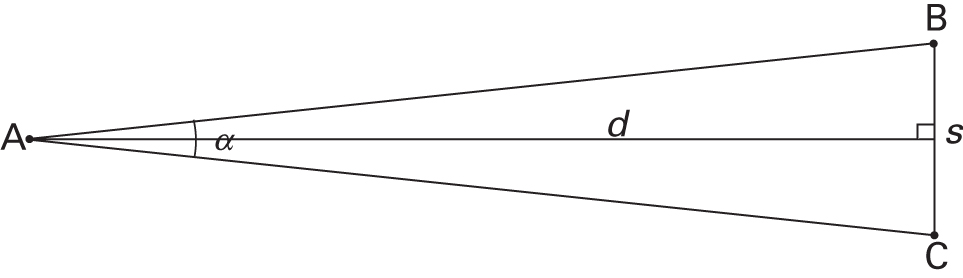

The Geometric Picture

For small angles (\(\alpha \ll 1\) rad):

\[\boxed{\alpha\,(\text{rad}) \approx \frac{s}{d}}\]

- \(\alpha\) = angular size (radians)

- \(s\) = true (physical) size

- \(d\) = distance to object

Physical meaning: Angular size is inversely proportional to distance.

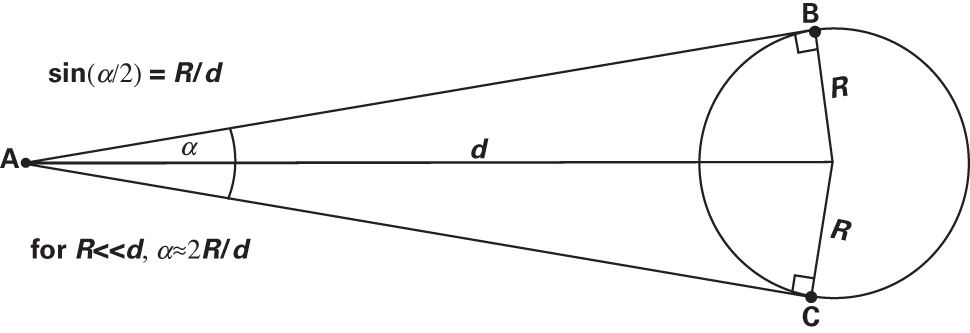

Why Does It Work? sin θ ≈ θ

The exact relation: \(\sin(\alpha/2) = R/d\)

For small \(\alpha\): \(\sin(\alpha/2) \approx \alpha/2\)

\[\implies \alpha \approx \frac{2R}{d} = \frac{s}{d}\]

How small is “small enough”?

At \(\alpha = 5°\), error is only 0.1%. For astronomy (arcseconds!), it’s essentially exact.

Quick Check 2: Small-Angle Scaling

If you double your distance from an object (keeping its true size fixed), its angular size:

A. Doubles

B. Quadruples

C. Halves

D. Quarters

Worked Example: Moon’s Diameter

Given:

- Angular size: \(\alpha = 0.5^\circ\)

- Distance: \(d = 3.84 \times 10^{10}\) cm

Convert: \(0.5^\circ = 1800'' \div 206{,}265 = 0.00873\) rad

Apply: \(s = \alpha \, d\)

\[s = (0.00873)(3.84 \times 10^{10} \text{ cm})\] \[\approx 3{,}350 \text{ km}\]

Actual lunar diameter: 3,474 km

Agreement within 4% — excellent!

. . .

The small-angle approximation works beautifully at half-degree scales.

Parallax

Distance from baseline geometry

Try It First: Parallax Demo

Before we derive anything, explore the interactive demo:

- Move the star closer and farther — watch the parallax angle change

- Closer star → larger parallax shift; the shift is measured against distant background stars

Now let’s derive why this works. → Full-screen demo

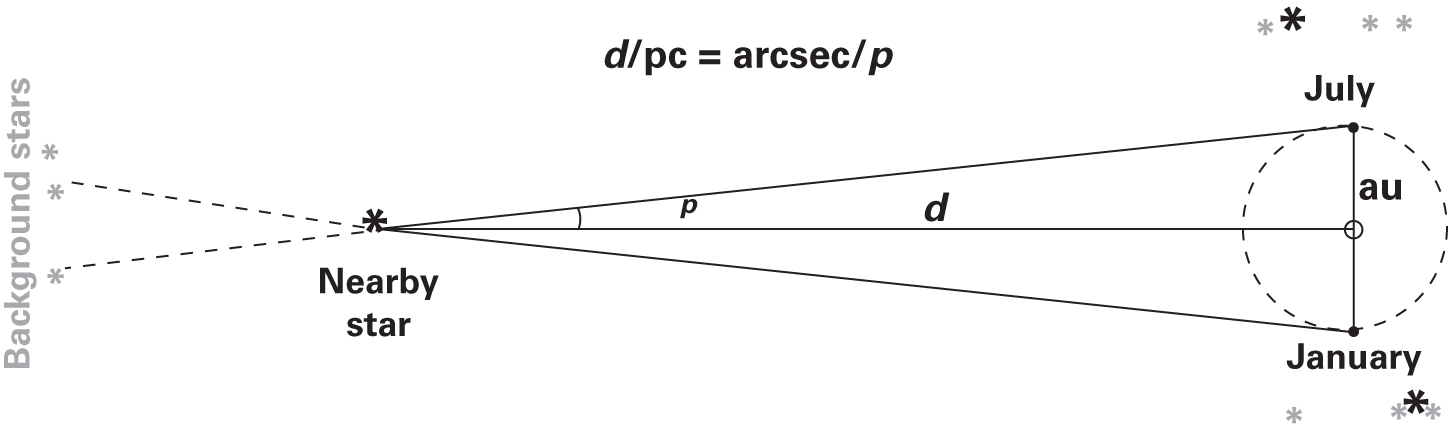

Parallax: The Geometry

As Earth orbits, a nearby star appears to shift against distant background stars.

The parallax angle \(p\) is defined as half the total shift, using a baseline of 1 AU (Earth’s orbital radius).

\[p\,(\text{rad}) \approx \frac{1\,\text{AU}}{d}\]

From Geometry to the Parsec

Convert parallax to arcseconds:

\[p\,('') = \frac{1\,\text{AU}}{d} \times 206{,}265\]

Define: 1 parsec (pc) = distance at which \(p = 1''\)

\[1\,\text{pc} = 206{,}265\,\text{AU} = 3.09 \times 10^{18}\,\text{cm} = 3.26\,\text{ly}\]

The distance formula becomes breathtakingly simple:

\[\boxed{d\,(\text{pc}) = \frac{1}{p\,('')}}\]

Quick Check 3: Parallax and Distance

Star A has parallax \(p = 0.5''\). Star B has parallax \(p = 0.1''\).

A. Star A is closer (2 pc vs 10 pc)

B. Star B is closer (10 pc vs 2 pc)

C. They’re at the same distance

D. Can’t tell without knowing luminosity

Worked Example: Proxima Centauri

Given: \(p = 0.768''\) (nearest star)

Step 1: Distance in parsecs \[d = \frac{1}{0.768} = 1.30\,\text{pc}\]

Step 2: Convert to centimeters \[d = 1.30 \times 3.09 \times 10^{18}\,\text{cm pc}^{-1}\] \[= 4.02 \times 10^{18}\,\text{cm}\]

Sanity check:

Nearby stars should be 1–5 pc. ✓

. . .

At 1.3 pc, Proxima is \(\sim 25\) trillion miles away — yet it’s the closest star.

This shows why parallax was historically so difficult to measure.

Our Nearest Neighbors

The nearest stellar neighborhood is a sparse place.

- Proxima Centauri: 1.3 pc

- Sirius: 2.6 pc

- Within 5 pc: only \(\sim 60\) known stellar systems

Most are red dwarfs too faint to see with the naked eye — the night sky is biased toward luminous stars.

The Parallax Revolution: Hipparcos to Gaia

| Mission | Precision | Stars | Distance reach |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ground (pre-1990) | \(\sim 50\) mas | \(\sim 1{,}000\) | \(\sim 20\) pc |

| Hipparcos (1989–93) | \(\sim 1\) mas | \(\sim 100{,}000\) | \(\sim 100\) pc |

| Gaia (2013–25) | \(\sim 10\) \(\mu\)as | \(\sim 1.8\) billion | \(\sim 10\) kpc |

Gaia’s \(100\times\) better precision directly translates to \(100\times\) better luminosity measurements for every star observed.

Active Learning Break 1: Think-Pair-Share

Problem: A star has parallax \(p = 0.050''\).

(a) What is its distance in parsecs?

(b) Convert to light-years.

(c) Could Hipparcos have measured this parallax? Could Gaia?

(d) Estimate the parallax of a star at the center of the Milky Way (\(\sim 8\) kpc away).

Reference: parallax geometry

Answers: (a) \(d = 1/0.050 = 20\) pc. (b) \(20 \times 3.26 = 65\) ly. (c) Yes (Hipparcos limit \(\sim 1\) mas \(= 0.001''\), this is much larger). (d) \(p = 1/8000 = 0.000125'' = 125\,\mu\)as — detectable by Gaia.

The Inverse-Square Law

How light spreads through space

Predict First

If you move twice as far from a light source, by what factor does the brightness change?

Think about why before we derive it.

Geometric Derivation: Concentric Spheres

A star emits luminosity \(L\) uniformly in all directions.

At distance \(d\), this energy is spread over a sphere of area \(4\pi d^2\).

Flux = energy per time per area:

\[\boxed{F = \frac{L}{4\pi d^2}}\]

Double the distance → flux drops by 4×. Ten times farther → flux drops by 100×.

Quick Check 4: Inverse-Square Law

You move 3× farther from a lamp. By what factor does the brightness drop?

A. 3× dimmer

B. 6× dimmer

C. 9× dimmer

D. 27× dimmer

Dimensional Analysis Check

Assume \(F \propto L^a \, d^b\)

| Quantity | Dimension |

|---|---|

| \(F\) (flux) | \([M\,T^{-3}]\) |

| \(L\) (luminosity) | \([M\,L^2\,T^{-3}]\) |

| \(d\) (distance) | \([L]\) |

Match exponents:

- Mass: \(1 = a\) → \(a = 1\)

- Time: \(-3 = -3a\) ✓

- Length: \(0 = 2a + b\) → \(b = -2\)

\[F \propto \frac{L}{d^2}\]

The \(4\pi\) comes from geometry — DA gives the scaling.

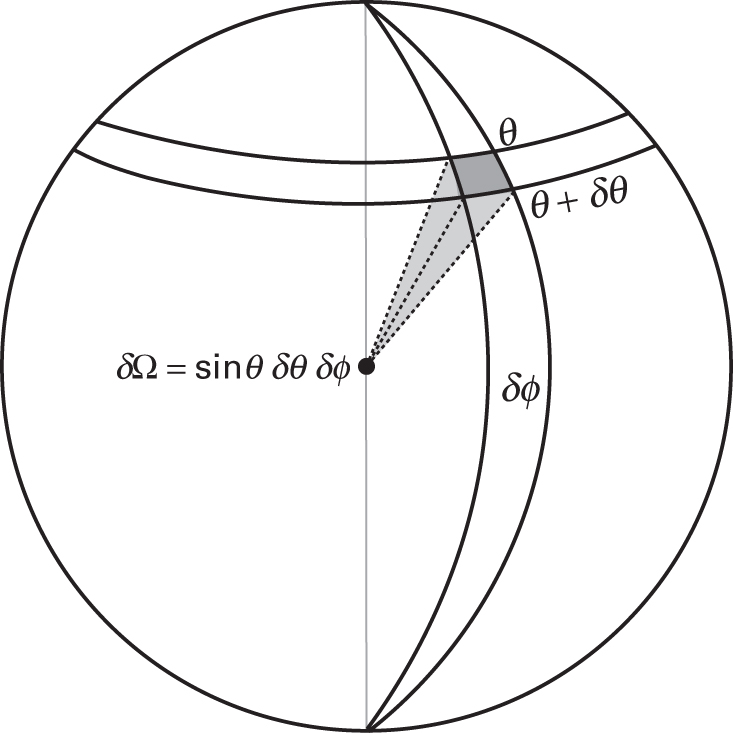

Where Does the 4π Come From?

A full sphere subtends \(4\pi\) steradians of solid angle.

Light from an isotropic source spreads evenly over this solid angle. At distance \(d\), the sphere has area \(4\pi d^2\).

So \(F = L/(4\pi d^2)\) simply says: total luminosity ÷ total area of the sphere you’re standing on.

Flux vs. Luminosity — Don’t Confuse Them!

Flux \(F\) (what you measure)

- Depends on where you stand

- Units: erg cm\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\)

- Changes with distance

Luminosity \(L\) (what the star emits)

- Intrinsic property of the star

- Units: erg s\(^{-1}\)

- Does not depend on distance

A dim red dwarf nearby can have the same observed flux as a luminous blue giant far away. You cannot determine luminosity from flux alone — you always need distance.

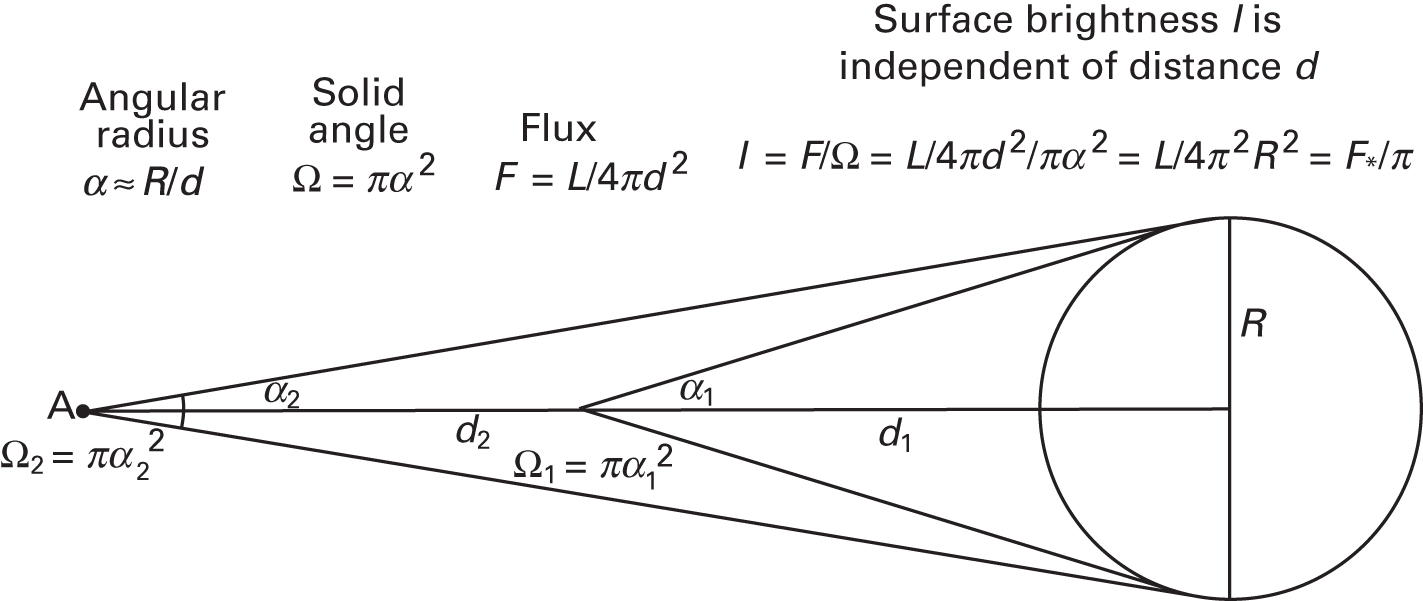

A Useful Surprise: Surface Brightness Is Distance-Independent

Flux drops as \(1/d^2\), but angular area also drops as \(1/d^2\).

Their ratio — surface brightness — is constant:

\[\frac{F}{\Delta\Omega} = \frac{L/(4\pi d^2)}{\pi R^2/d^2} = \frac{L}{4\pi^2 R^2}\]

This is why galaxy images don’t “fade” at greater distances — they just get smaller. Surface brightness depends only on the source, not distance.

From Distance to Luminosity

The measurement chain

The Complete Measurement Chain

- Observe position shifts → parallax \(p\)

- Model parallax geometry → distance \(d = 1/p\)

- Observe brightness → flux \(F\)

- Model inverse-square law → \(L = 4\pi d^2 F\)

- Infer luminosity \(L\)

Three rearrangements of one equation:

| Know | Find | Formula |

|---|---|---|

| \(L, d\) | \(F\) | \(F = L/(4\pi d^2)\) |

| \(F, d\) | \(L\) | \(L = 4\pi d^2 F\) |

| \(L, F\) | \(d\) | \(d = \sqrt{L/(4\pi F)}\) |

Worked Example: Solar Luminosity

Given:

- Solar constant: \(F_\odot = 1.4 \times 10^6\) erg cm\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\)

- Earth–Sun distance: \(d = 1.5 \times 10^{13}\) cm

Calculate:

\[L_\odot = 4\pi d^2 F\] \[= 4\pi (1.5 \times 10^{13})^2 (1.4 \times 10^6)\] \[= 4\pi \times 3.15 \times 10^{32}\] \[\approx 3.96 \times 10^{33}\,\text{erg s}^{-1}\]

Standard value: \(L_\odot = 3.83 \times 10^{33}\) erg s\(^{-1}\)

Agreement within 4%!

This is how we know the Sun’s luminosity. Every star on the HR diagram uses this same method.

Error Propagation: Why Precision Matters

\[d = \frac{1}{p} \implies \frac{\delta d}{d} \approx \frac{\delta p}{p}\]

\[L = 4\pi d^2 F \implies \frac{\delta L}{L} \approx 2\,\frac{\delta d}{d}\]

The complete chain:

10% parallax error → \(\sim 10\)% distance error → \(\sim\)20% luminosity error

Errors double going from distance to luminosity because \(L \propto d^2\).

Gaia’s \(100\times\) parallax improvement → \(100\times\) better luminosity.

Worked Example: Full Chain — Parallax to Astrophysics

Given: \(p = 0.214''\), \(F = 1.1 \times 10^{-7}\) erg cm\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\)

Step 1: \(d = 1/0.214 = 4.67\) pc \(= 1.44 \times 10^{19}\) cm

Step 2: \[L = 4\pi (1.44 \times 10^{19})^2 (1.1 \times 10^{-7})\] \[\approx 2.9 \times 10^{32}\,\text{erg s}^{-1}\]

Step 3: \(L/L_\odot = 2.9 \times 10^{32} / 3.83 \times 10^{33} \approx 0.075\)

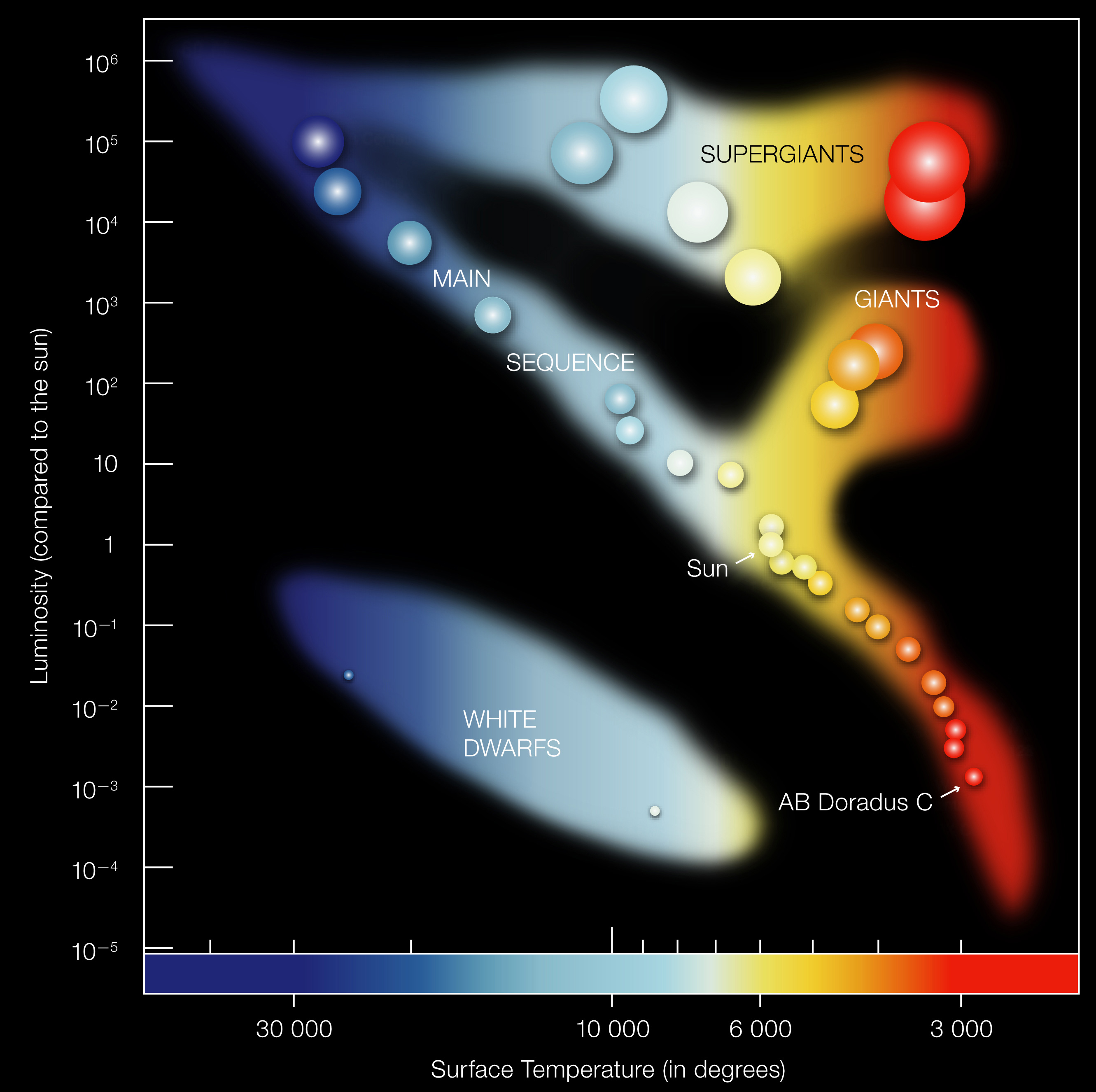

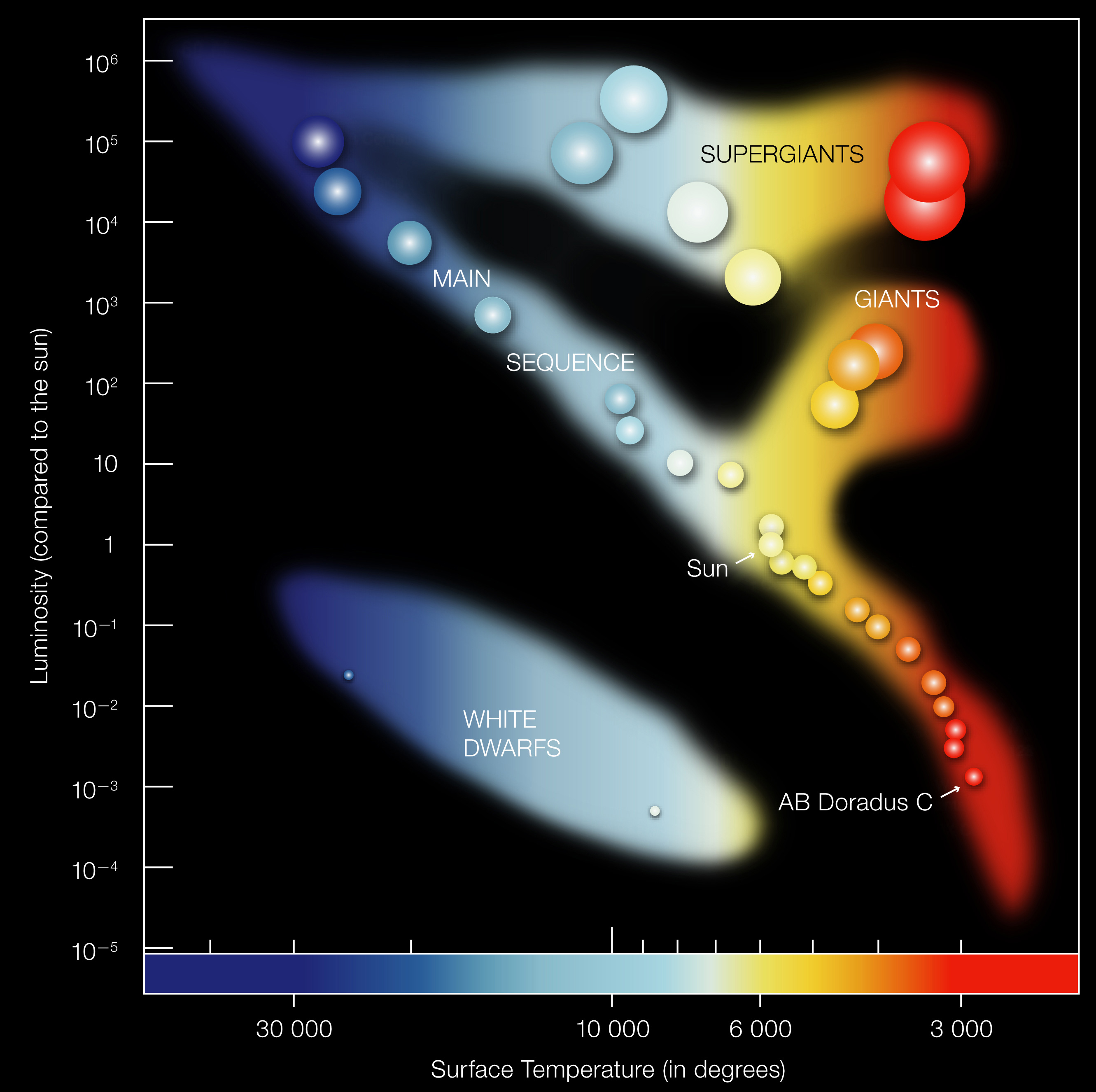

This star at \(L \approx 0.08\,L_\odot\) sits on the lower main sequence — a late K or early M dwarf. These small, cool, red stars dominate the Galaxy by number.

Active Learning Break 2: Synthesis Problem

A star has parallax \(p = 0.1''\) and flux \(F = 10^{-11}\) erg cm\(^{-2}\) s\(^{-1}\).

- Distance? (\(d = 10\) pc \(= 3.09 \times 10^{19}\) cm)

- Luminosity? (\(L = 4\pi d^2 F \approx 1.2 \times 10^{29}\) erg s\(^{-1}\))

- In solar luminosities? (\(L/L_\odot \approx 3 \times 10^{-5}\))

- What kind of star? (Very faint red dwarf — \(\sim 30{,}000\times\) dimmer than the Sun!)

Where does your answer land on the HR diagram?

Quick Check 5: Putting It Together

Two stars have identical flux. Star A is at 10 pc, Star B at 100 pc. Which has higher luminosity, and by what factor?

A. Star A, by 10×

B. Star B, by 10×

C. Star A, by 100×

D. Star B, by 100×

Beyond Parallax

Standard candles and the distance ladder

The Parallax Horizon

Parallax works out to:

- \(\sim 100\) pc from ground-based telescopes

- \(\sim 10\) kpc with Gaia

But the Milky Way is \(\sim 30\) kpc across, and Andromeda is \(\sim 770\) kpc away.

How do we measure distances beyond parallax?

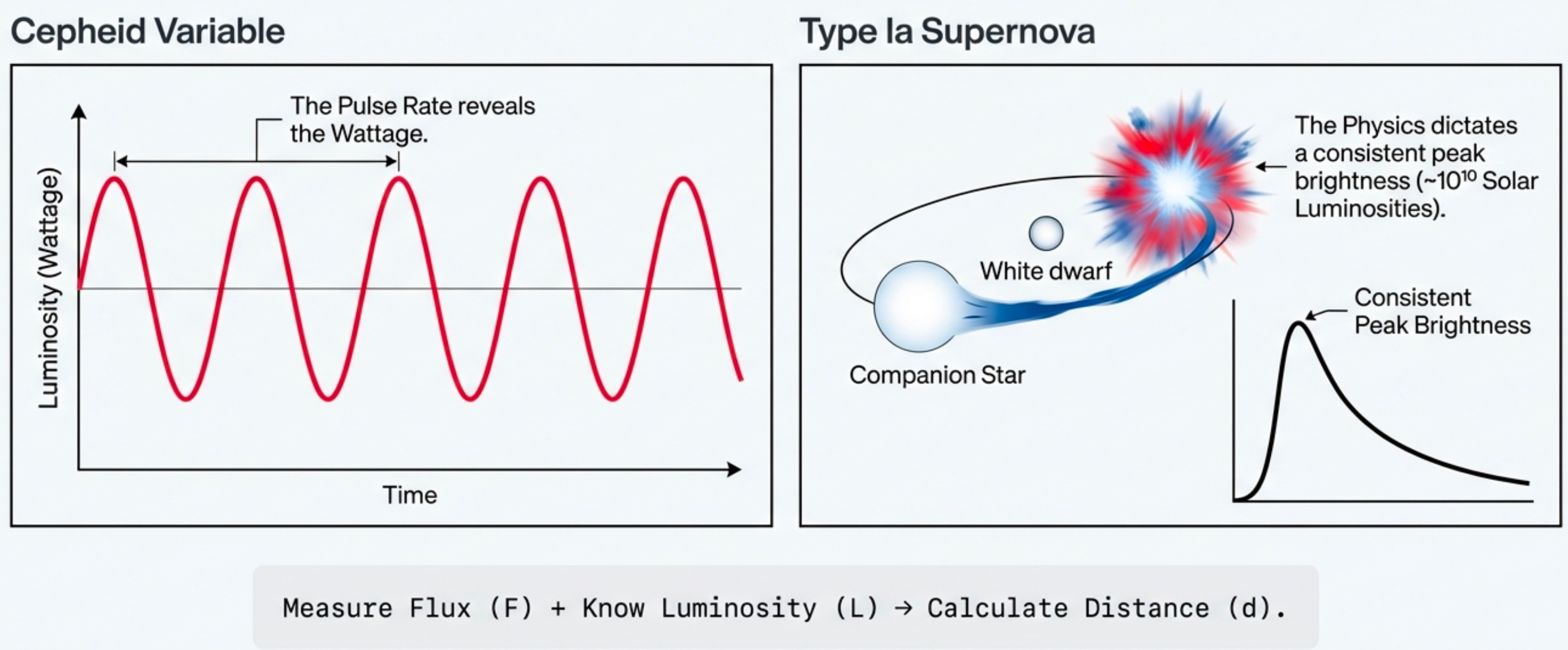

Standard Candles: Using the ISL Backwards

If we know a star’s luminosity \(L\), we can measure its flux \(F\) and infer distance:

\[\boxed{d = \sqrt{\frac{L}{4\pi F}}}\]

Objects with known or determinable luminosity are called standard candles.

Cepheids and Type Ia Supernovae

Cepheid Variables

- Pulsating stars; period → luminosity

- Discovered by Henrietta Leavitt (1912)

- Reach: \(\sim 30\) Mpc

- Hubble used them to prove Andromeda is a separate galaxy (1920s)

Type Ia Supernovae

- Thermonuclear explosions of white dwarfs

- Peak luminosity: ~few \(\times 10^9 L_\odot\)

- Reach: \(\sim 10\) Gpc (cosmological!)

- Led to the discovery of dark energy (2011 Nobel Prize)

Massive, luminous stars are rare and distant — we need long-reach methods to study them. Standard candles solve this.

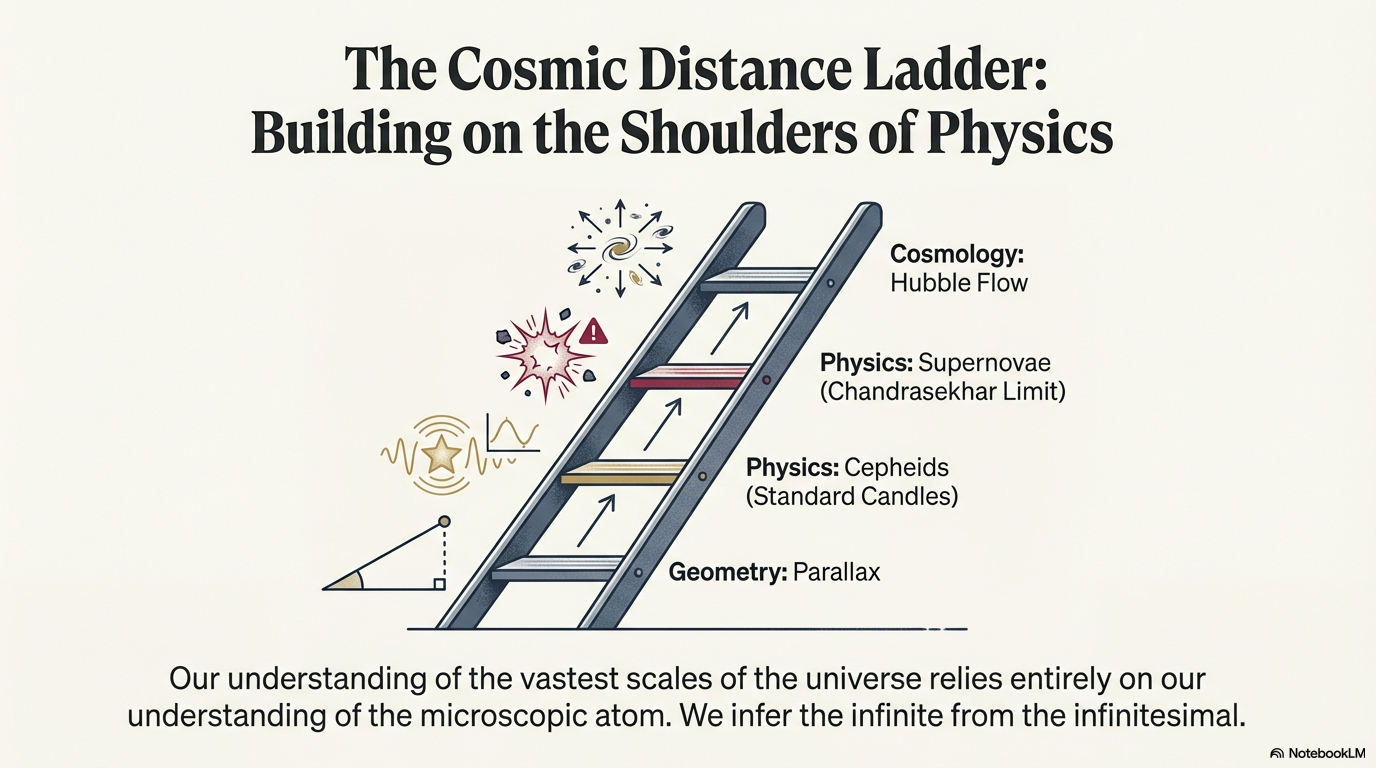

The Cosmic Distance Ladder

Each rung is calibrated by the one below. The entire cosmic distance scale rests on getting nearby parallaxes right — which is why Gaia matters for all of astronomy.

Wrapping Up

Summary: Key Equations

| Equation | What it does |

|---|---|

| \(\alpha \approx s/d\) | Angular size ↔︎ true size + distance |

| \(d\,(\text{pc}) = 1/p\,('')\) | Parallax → distance |

| \(F = L/(4\pi d^2)\) | Inverse-square law |

| \(L = 4\pi d^2 F\) | Luminosity from flux + distance |

| \(d = \sqrt{L/(4\pi F)}\) | Standard candle distance |

flowchart LR P["Position shift\n(Observable)"] --> G["Parallax geometry\n(Model)"] G --> D["Distance d\n(Inference)"] F["Flux F\n(Observable)"] --> ISL["Inverse-square law\n(Model)"] D --> ISL ISL --> L["Luminosity L\n(Inference)"] L --> HR["HR Diagram"] style P fill:#dbeafe,stroke:#2563eb style F fill:#dbeafe,stroke:#2563eb style G fill:#fef3c7,stroke:#d97706 style ISL fill:#fef3c7,stroke:#d97706 style D fill:#dcfce7,stroke:#16a34a style L fill:#dcfce7,stroke:#16a34a style HR fill:#f3e8ff,stroke:#9333ea

The Takeaway

If you forget everything else from today, remember this:

Distance is the master key.

Measure distance, and luminosity becomes knowable — the first step to understanding any star.

Questions?

Common questions at this point:

- “Why can’t we just use radar to measure star distances?”

- “What if dust absorbs the light — doesn’t that break the inverse-square law?”

- “How do we know the period-luminosity relation for Cepheids is correct?”

Looking Ahead

Next time (Lecture 2): Surface Flux & Colors of Stars

- Stefan-Boltzmann law: \(L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4\)

- Wien’s law: peak wavelength → temperature

- Stellar radii from luminosity + temperature

Before then:

- Read: Lecture 1 reading (distance & parallax)

- Try: Practice problems 3–5 (parallax conversions & luminosity calculations)

Equation Toolbox — Your Reference Card

| Equation | Form | When to use |

|---|---|---|

| Angle conversions | \(1^\circ = 3600''\); \(1' = 60''\) | Angular unit conversion |

| Arcsec ↔︎ radians | \(1\,\text{rad} = 206{,}265''\) | Bridging measurement systems |

| Small-angle | \(\alpha\,(\text{rad}) \approx s/d\) | Angular size, true size, distance |

| Parallax–distance | \(d\,(\text{pc}) = 1/p\,('')\) | Parallax to distance |

| Inverse-square law | \(F = L/(4\pi d^2)\) | Flux, luminosity, distance |

| Luminosity inference | \(L = 4\pi d^2 F\) | Computing luminosity |

| Standard candle | \(d = \sqrt{L/(4\pi F)}\) | Distance from known luminosity |

ASTR 201 • Module 2, Lecture 1