Lecture 2: Surface Flux and Colors

From color to temperature to radius

February 12, 2026

Today’s Targets (What you should be able to do after class)

By the end of Lecture 2, you can:

- Distinguish received flux \(F\) from surface flux \(F_\star\) (they answer different questions).

- Use Stefan-Boltzmann to connect \(L\), \(R\), \(T\) and do scaling quickly.

- Use Wien’s law to infer \(T\) from \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) (especially with ratios).

- Explain (briefly, correctly) the ultraviolet catastrophe and why Planck mattered.

- Read the HR diagram as a radius map in disguise (preview).

The Big Idea

Astronomy is an inference machine.

We measure photons at Earth (brightness + spectrum) and infer physical properties of stars:

- \(F\) + \(d\) \(\rightarrow\) \(L\) (Lecture 1)

- color / \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) \(\rightarrow\) \(T\) (today)

- \(L\) and \(T\) \(\rightarrow\) \(R\) (today)

Orion Puzzle: Same Luminosity, Wildly Different Size

Rigel (blue) and Betelgeuse (red) can have comparable luminosities yet very different radii.

- Blue star: hotter \(\rightarrow\) can be smaller and still luminous

- Red star: cooler \(\rightarrow\) must be huge to be equally luminous

Warning

Same luminosity does not imply same radius. “Bright” is ambiguous — always say which quantity you mean.

Commit to a Prediction

If two stars have the same luminosity and one is cooler, that cooler star is most likely:

- smaller

- larger

- at the same radius

- impossible to determine from physics

Vocabulary Lock-In: The Three Core Quantities

Luminosity \(L\) Total power output (intrinsic). Units: erg/s (or W).

Flux \(F\) Power per area measured at a location (depends on where you stand). Units: erg s\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-2}\).

Radius \(R\) Physical size of star. Units: cm (or \(R_\odot\)).

Two Fluxes — Same Symbol Family, Different Meaning

These answer two different questions:

Received flux (what we measure here)

\[ F = \frac{L}{4\pi d^2} \] Depends on distance \(d\).

Surface flux (what the star emits per cm² of surface)

\[ F_\star = \frac{L}{4\pi R^2} \] Depends on star size \(R\).

Tip

Say it out loud: - \(F\): “How bright does it look here?” - \(F_\star\): “How intense is the radiation at the surface?”

Think–Pair–Share (2 minutes): Scaling Intuition

Answer using proportional reasoning:

- If \(d \rightarrow 2d\) with \(L\) fixed, what happens to \(F\)?

- If \(R \rightarrow 2R\) with \(L\) fixed, what happens to \(F_\star\)?

- What is physically different about those two changes?

Important

Both changes quarter the flux — but for totally different reasons.

Geometric Bridge: Connecting the Two Fluxes

Divide the two equations:

\[ \frac{F}{F_\star} = \frac{R^2}{d^2} \]

Meaning:

- Stars are tiny on the sky: \(R \ll d\)

- So only a tiny fraction of the surface emission reaches Earth

Tip

This ratio is basically “how much of the star’s surface sphere you intercept.”

What We Need Next

To get radius \(R\), we need a link between:

- how much power per cm² the surface emits (\(F_\star\))

- and temperature \(T\)

That link is thermal physics:

\[ F_\star = \sigma T^4 \]

Then luminosity is surface flux × area.

The Engine: Stefan–Boltzmann (Surface → Total)

Surface flux of a blackbody: \[ F_\star = \sigma T^4 \]

Total luminosity = surface flux × surface area: \[ L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4 \]

Important

Interpretation: - \(R^2\) is “how much surface you have” - \(T^4\) is “how hard each cm² radiates”

What Stefan–Boltzmann Is Saying (in plain English)

- Temperature is a steep lever: small \(T\) changes → huge luminosity changes.

- Radius is a quadratic lever: bigger star → more emitting area.

At fixed radius: \[ T \rightarrow 2T \quad \Rightarrow \quad L \rightarrow 16L \]

Tip

This is why “hot” matters so much in stars: \(T^4\) is ruthless.

Mini-Prediction

A star twice as hot as another, with the same radius, is how much more luminous?

- \(2\times\)

- \(4\times\)

- \(16\times\)

- \(32\times\)

The Key Inference: Fixed Luminosity ⇒ Radius–Temperature Tradeoff

If luminosity is fixed:

\[ L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4 = \text{constant} \Rightarrow R^2T^4=\text{constant} \Rightarrow R \propto T^{-2} \]

Translation: at the same luminosity…

- hotter star → smaller radius

- cooler star → larger radius

Warning

This is the Orion puzzle answer in one line.

Prediction Before the Demo (write 3 short answers)

When temperature increases in a blackbody spectrum, predict:

- Does \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) shift to shorter or longer wavelengths?

- Does the total area under the curve increase a little or a lot?

- What happens at very short wavelengths (UV)?

Demo Protocol: What We’re Testing

During the demo, you’re watching for three signatures:

- Peak shift (Wien’s law): \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) moves with \(T^{-1}\)

- Area growth (Stefan–Boltzmann): total emission grows like \(T^4\)

- UV behavior (quantum): short-wavelength emission gets suppressed

Tip

This demo is not entertainment. It’s an experiment.

Live Demo: Blackbody Radiation

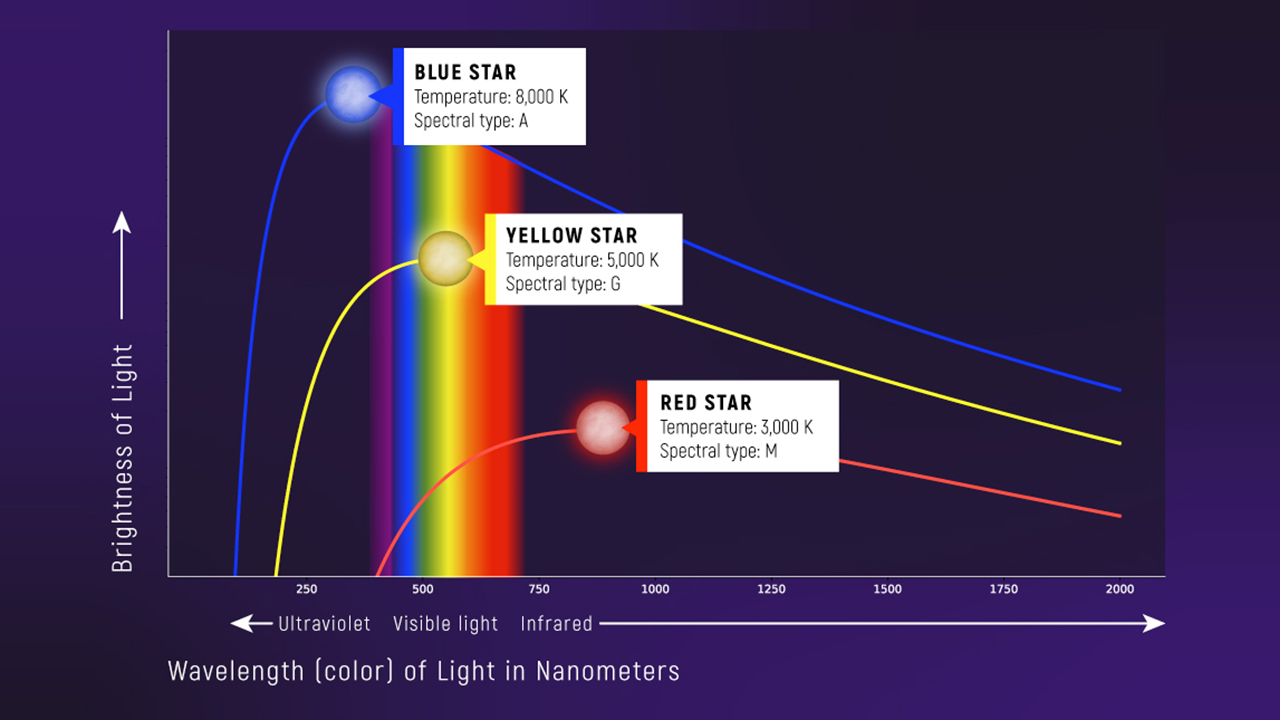

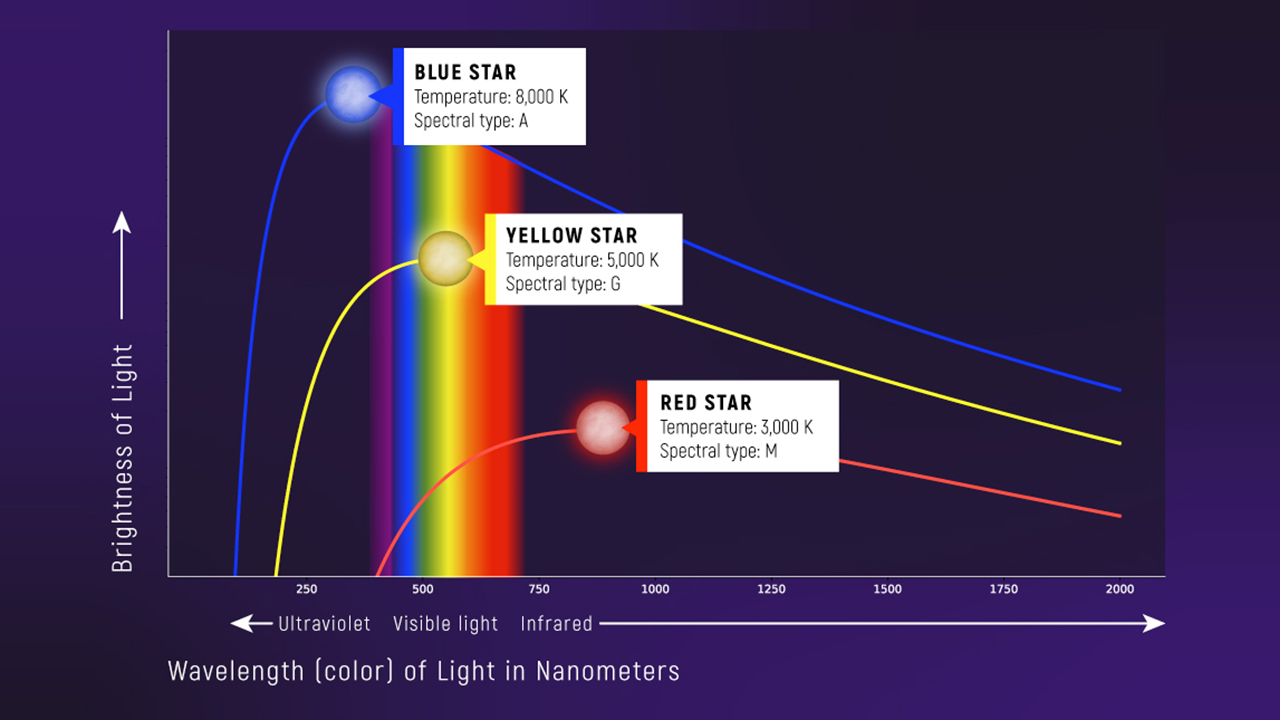

Anchor Image: Planck Curves (static reference)

What to notice:

- Hotter curves peak at shorter wavelengths

- Hotter curves have much larger total area (more luminosity)

UV Catastrophe: What Classical Physics Predicted

At long wavelength, classical physics gives the Rayleigh–Jeans form:

\[ B_\lambda \propto \frac{T}{\lambda^4} \]

If you extend that to \(\lambda \rightarrow 0\):

Warning

\(B_\lambda \rightarrow \infty\) → infinite energy output. That would mean hot objects radiate unlimited UV. The universe would be absurdly UV-bright.

Planck’s Move (1900): Quantization

Planck assumed energy exchange happens in packets:

\[ E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1} \tag{1}\]

Meaning:

- short wavelength ↔︎ high frequency ↔︎ high photon energy

- high-frequency photons are expensive

- so UV emission is suppressed

Important

That “UV cutoff” behavior you saw in the demo is quantum mechanics in action.

The Fix: A Finite, Physical Spectrum

\[ B_\lambda(T)=\frac{2hc^2}{\lambda^5}\cdot\frac{1}{e^{hc/(\lambda k_B T)}-1} \tag{2}\]

Key behavior:

- Long wavelengths: classical approximation emerges

- Short wavelengths: exponential suppression prevents divergence

- Total emitted power becomes finite → stars can exist

Wien’s Law: Color → Temperature (the fast tool)

Wien’s displacement law (peak in \(B_\lambda\)):

\[ \lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1} \tag{3}\]

Interpretation:

- hotter → smaller \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) (bluer peak)

- cooler → larger \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) (redder peak)

Tip

Use ratio form whenever possible — constants cancel.

Wien Ratio Form (Exam-Safe)

From \(\lambda_{\rm peak} = b/T\):

\[ \frac{T_1}{T_2} = \frac{\lambda_{\rm peak,2}}{\lambda_{\rm peak,1}} \]

So relative to the Sun:

\[ \frac{T_\star}{T_\odot} = \frac{\lambda_{\rm peak,\odot}}{\lambda_{\rm peak,\star}} \]

Ratio Example: 500 nm vs 250 nm

Given:

- \(\lambda_{\rm peak,\odot} \approx 500\,\text{nm}\)

- \(\lambda_{\rm peak,\star} \approx 250\,\text{nm}\)

Then:

\[ \frac{T_\star}{T_\odot} = \frac{500}{250} = 2 \Rightarrow T_\star \approx 2(5800\,\text{K}) \approx 1.16\times10^4\,\text{K} \]

Tip

Halving peak wavelength doubles temperature.

Quick Check: Direction

If \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\) shifts to a longer wavelength, the star is:

- hotter

- cooler

- unchanged in temperature

- impossible to classify

Radius Inference: Solve Stefan–Boltzmann for \(R\)

From \[ L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4 \]

Solve: \[ R = \left(\frac{L}{4\pi\sigma T^4}\right)^{1/2} \]

Warning

Common mistake: forgetting the \(1/2\) power (writing \(R^2\) by accident).

Solar-Unit Form (Cleaner, Fewer Mistakes)

Divide by the Sun’s Stefan–Boltzmann law:

\[ \frac{L}{L_\odot} = \left(\frac{R}{R_\odot}\right)^2 \left(\frac{T}{T_\odot}\right)^4 \]

Solve for radius:

\[ \frac{R}{R_\odot} = \left( \frac{L/L_\odot}{(T/T_\odot)^4} \right)^{1/2} \]

Tip

This is the “no constants, no unit pain” form.

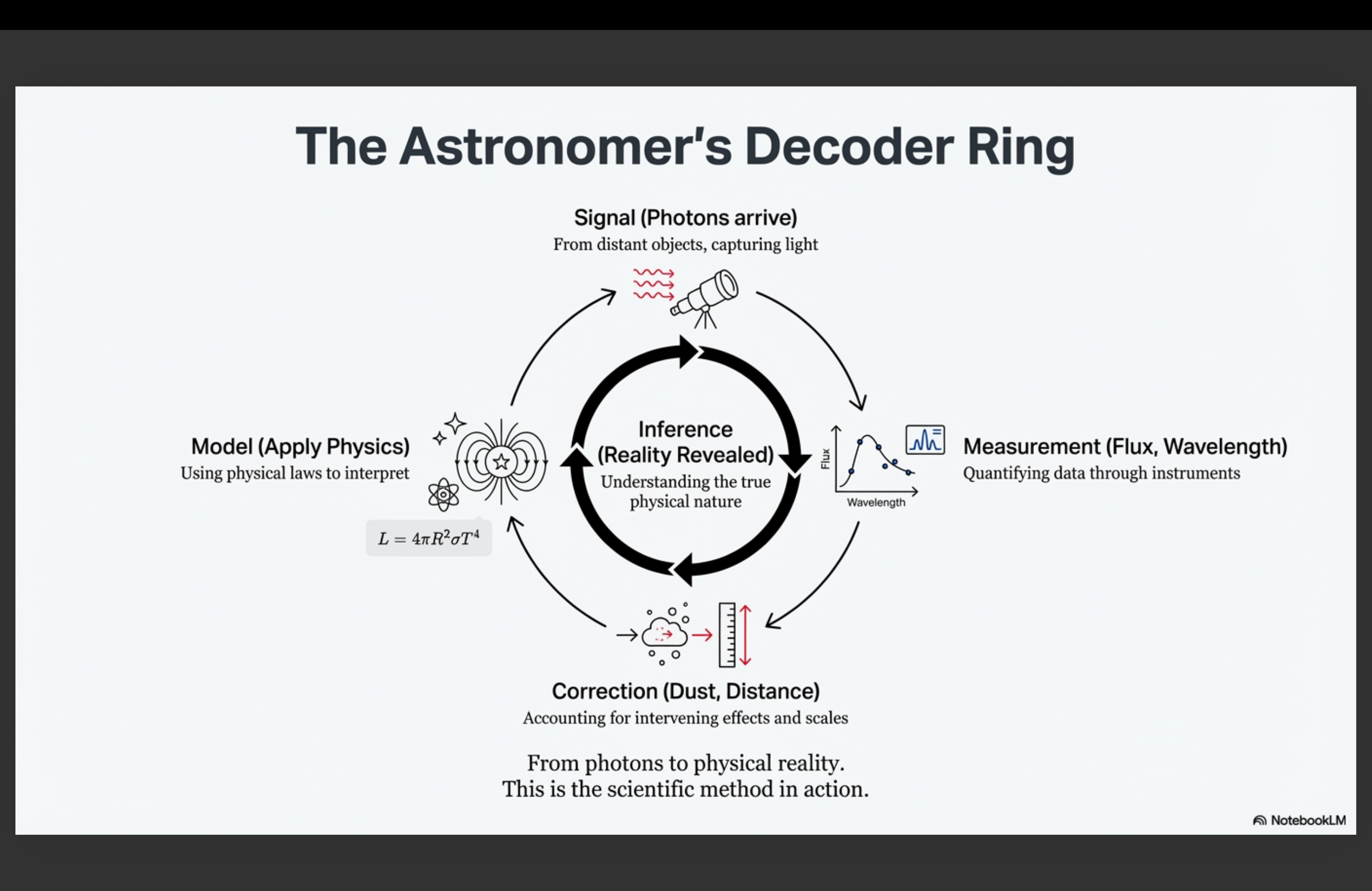

The Astronomer’s Decoder Ring (Today)

Observable \(\rightarrow\) Model \(\rightarrow\) Inference

- Measure brightness + distance: \(F + d \rightarrow L\)

- Measure color/peak: \(\lambda_{\rm peak} \rightarrow T\)

- Combine: \((L, T) \rightarrow R\) via Stefan–Boltzmann

How Do We Know This Isn’t Just Math Magic?

We can validate radii with independent methods:

- Eclipsing binaries: geometry + timing gives radii directly

- Interferometry: angular size + distance → physical radius

- Spectral energy distributions: fit full spectrum for \(T\) and bolometric flux

Important

In astronomy, inference becomes knowledge when independent methods agree.

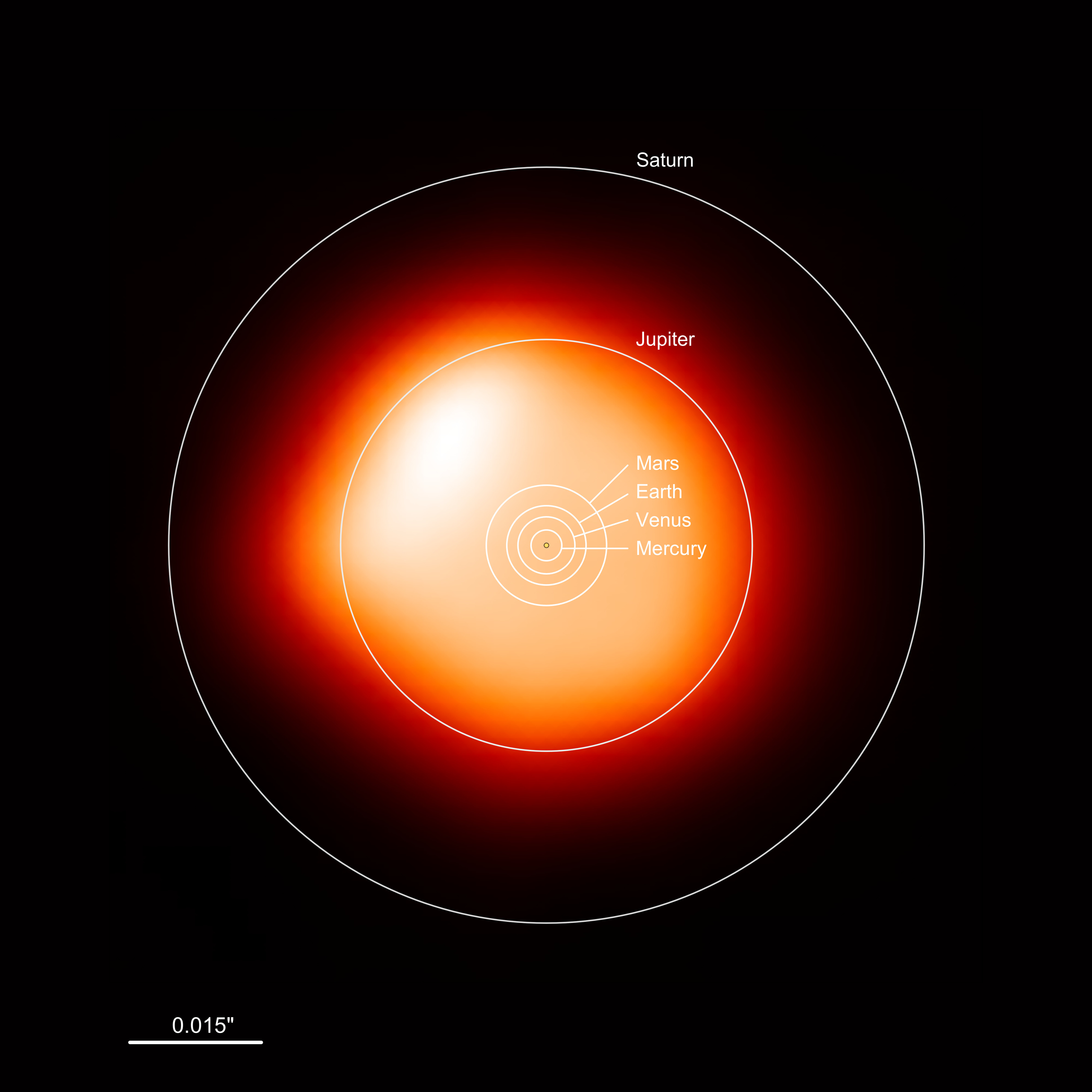

Betelgeuse: Qualitative Inference (words first)

Betelgeuse is:

- cooler than the Sun (\(T \sim 3500\,\text{K}\))

- incredibly luminous (\(L \sim 10^5 L_\odot\))

Cool surface means low \(F_\star=\sigma T^4\), yet total luminosity is huge.

Important

Only one way to reconcile both: enormous emitting area → large radius.

Betelgeuse Scale (let this land)

Order-of-magnitude radius:

\[ R \sim 10^3 R_\odot \]

Roughly hundreds to about a thousand solar radii.

Warning

Spoiler alert: Betelgeuse is an evolved massive star, a red supergiant.

Mini-Activity (8 minutes): Hotter, Same Luminosity

Work in pairs. Write one equation + one sentence.

A star has:

\(L = L_\odot\)

\(T = 2T_\odot\)

Start from:

\[ L \propto R^2 T^4 \]

Tasks:

Find \(R/R_\odot\).

Predict: bluer or redder than the Sun.

Place it relative to the Sun on the HR diagram (left/right, up/down).

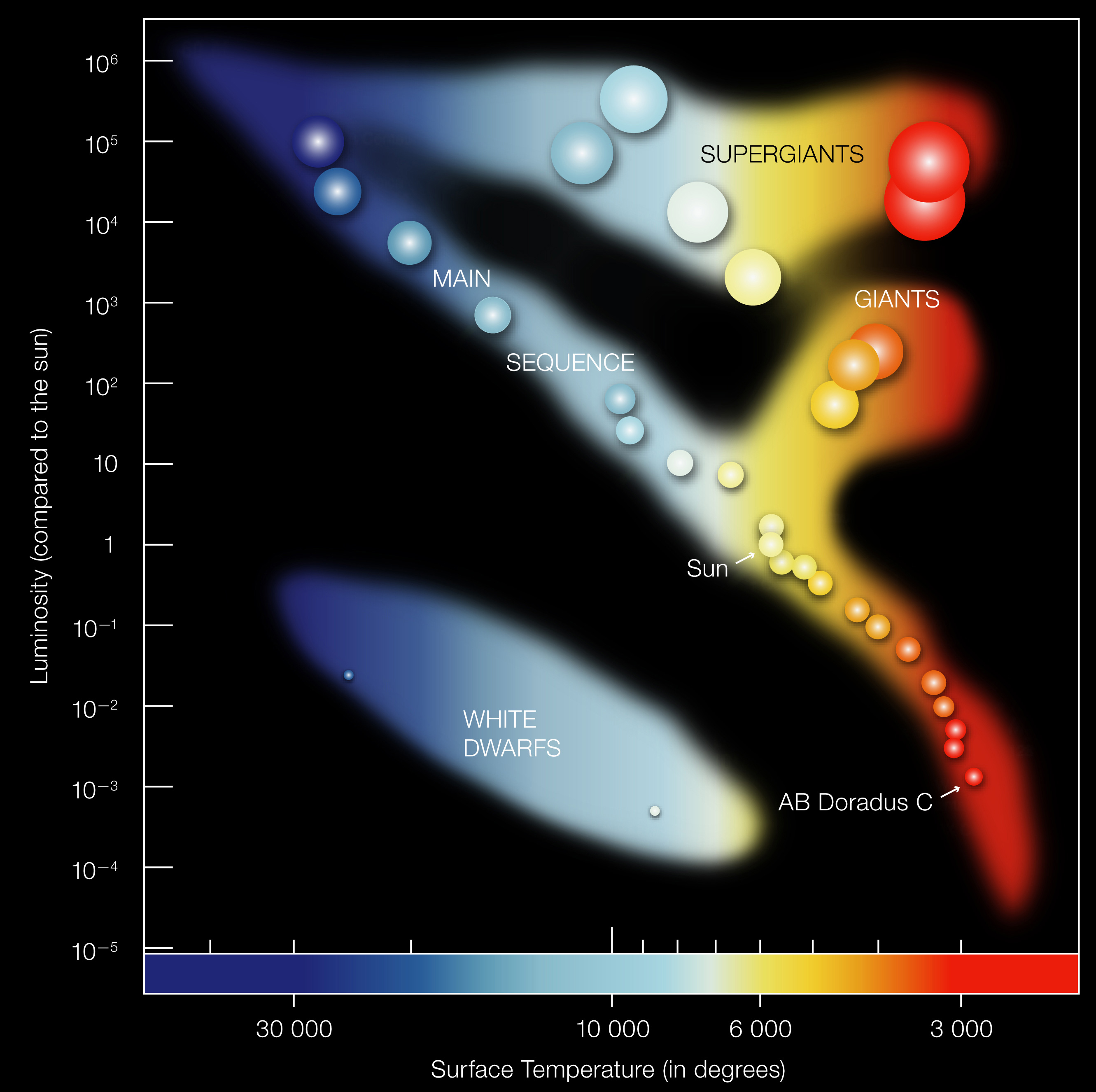

Use this map for directional placement only.

Mini-Activity Debrief

At fixed luminosity:

\[ R \propto T^{-2} \Rightarrow \frac{R}{R_\odot} = \left(\frac{T}{T_\odot}\right)^{-2} = (2)^{-2} = \frac{1}{4} \]

So the star is hotter (bluer) and smaller but with same \(L\).

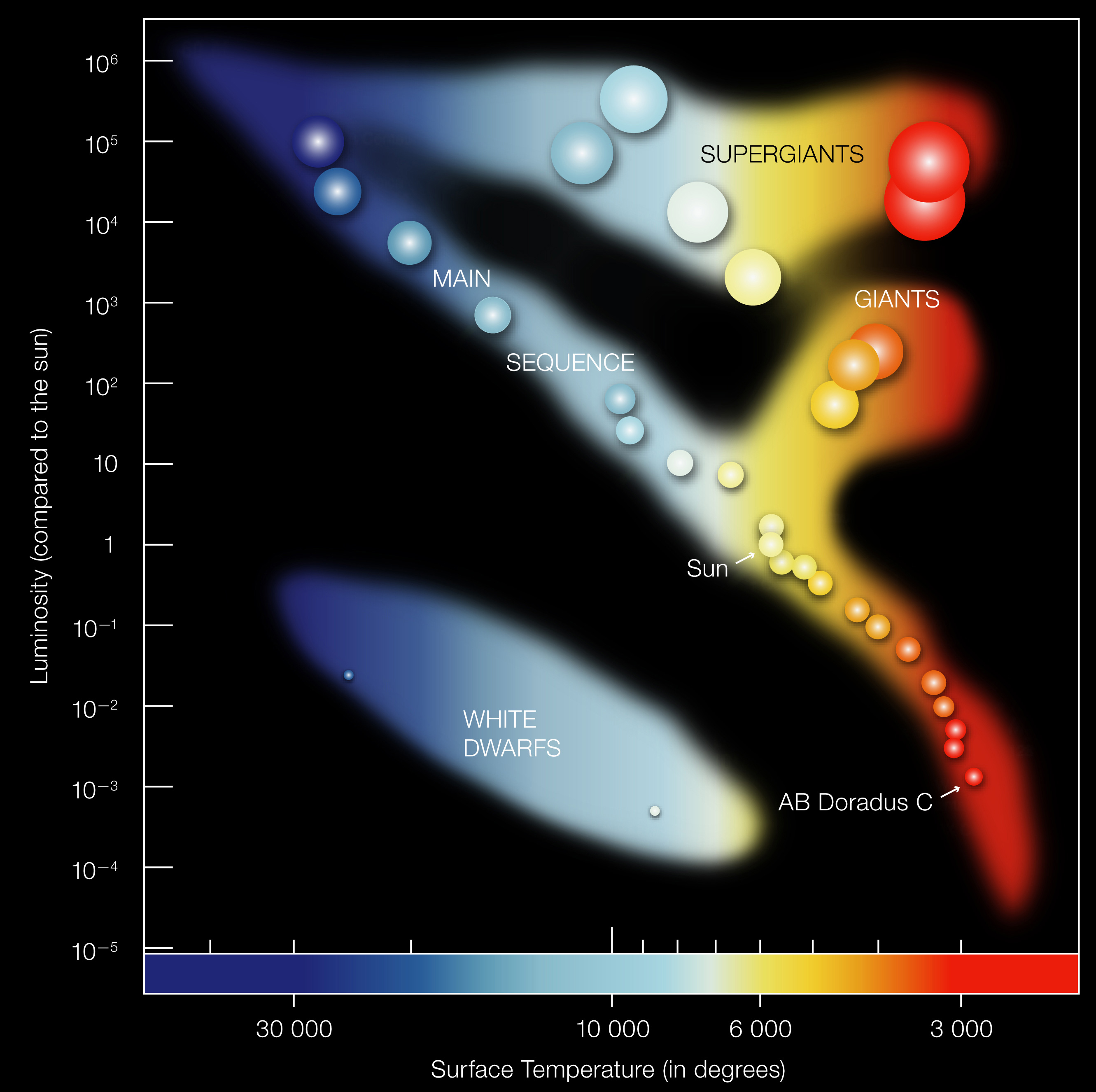

HR Diagram Preview: Radius Map in Disguise

Interpretation using \[ L \propto R^2T^4 \]

- Cool + luminous \(\rightarrow\) large \(R\) (giants/supergiants)

- Hot + dim \(\rightarrow\) small \(R\) (white dwarfs)

Hotter is to the left (historical convention).

Synthesis Quiz: What Determines Apparent Brightness?

To decide whether Betelgeuse placed at \(10\,\mathrm{pc}\) would appear brighter or dimmer than Sirius, which quantities must you compare directly?

- surface flux and temperature

- luminosity and distance

- radius and peak wavelength

- color index and surface flux

Exit Ticket (2 sentences)

Write two sentences (this is your study summary):

- “Color tells us ______ because ______.”

- “At fixed luminosity, hotter means ______ radius because ______.”

Summary Takeaways: The Intrinsic Triad

The three intrinsic stellar properties are:

- Luminosity \(L\): total power output

- Effective temperature \(T_{\text{eff}}\): surface temperature

- Radius \(R\): physical size

These form a closed physical relationship: \[ L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4 \]

If you know any two, physics constrains the third.

Important

Astronomy is an inference machine: \[ \text{observables} \rightarrow \text{model} \rightarrow \text{physical reality} \]

\[ T \rightarrow 2T \quad \Rightarrow \quad L \rightarrow 16L \] \[ R \rightarrow 2R \quad \Rightarrow \quad L \rightarrow 4L \]

Summary Takeaways: Flux vs Surface Flux

Received flux (observer-dependent): \[ F = \frac{L}{4\pi d^2} \] Depends on distance \(d\).

This tells us how bright a star looks from Earth.

Surface flux (intrinsic): \[ F_\star = \frac{L}{4\pi R^2} = \sigma T^4 \] Depends on stellar properties, not observer location.

This tells us how intensely each cm\(^2\) of stellar surface radiates.

Warning

Key distinction: \(F\) changes when you move; \(F_\star\) changes only if the star changes.

Summary Takeaways: The Inference Chain

\[ F + d \rightarrow L,\quad \lambda_{\rm peak} \rightarrow T,\quad (L,T) \rightarrow R \]

Use Wien’s law for temperature: \[ \lambda_{\rm peak} \propto \frac{1}{T} \]

Then solve Stefan-Boltzmann for radius: \[ R=\left(\frac{L}{4\pi \sigma T^4}\right)^{1/2} \]

Case-study conclusion (Rigel vs Betelgeuse):

- Similar luminosity can coexist with very different radii.

- Cooler stars must have much larger surface area to match high \(L\).

- This logic is what maps stars onto the H-R diagram as a radius structure.

Next Time

Next: spectral lines and classification refine temperature and reveal composition.

Today you built the core chain: \(F + d \rightarrow L\), \(\lambda_{\rm peak} \rightarrow T\), \((L,T)\rightarrow R\).

Appendix (Optional, Study Support)

The next slides:

- Show why the Wien ratio form works algebraically

- Derive Wien’s law from the Planck function (optimization)

- Are not required for in-class problem solving

- Are fully fair game for conceptual exam questions

Warning

Optional appendix: requires comfort with derivatives and basic optimization.

Appendix A: Why the Wien Ratio Form Cancels the Constant

Start from Wien’s law:

\[ \lambda_{\rm peak} = \frac{b}{T} \]

Write it for two stars:

\[ \lambda_1 = \frac{b}{T_1}, \quad \lambda_2 = \frac{b}{T_2} \]

Take the ratio:

\[ \frac{\lambda_1}{\lambda_2} = \frac{(b/T_1)}{(b/T_2)} = \frac{T_2}{T_1} \]

Rearrange:

\[ \frac{T_1}{T_2} = \frac{\lambda_2}{\lambda_1} \]

Important

The constant \(b\) cancels automatically. That is why the ratio method is fast and safe.

Why Calculus Matters: Deriving Wien’s Law

Warning

Optional extension for interested students: this section uses calculus and is not required for this course.

Planck’s function (per wavelength form):

\[ B_\lambda(T) = \frac{2hc^2}{\lambda^5} \frac{1}{e^{hc/(\lambda kT)} - 1} \]

Goal: find the wavelength at the maximum, \(\lambda_{\rm peak}\).

\[ \frac{dB_\lambda}{d\lambda} = 0 \]

Peak-finding on this curve is exactly where calculus enters.

Step 1: Define a Dimensionless Variable

Let:

\[ x = \frac{hc}{\lambda kT} \]

Then:

\[ \lambda = \frac{hc}{xkT} \]

We rewrite Planck’s function in terms of \(x\).

Step 2: Express the Peak Condition in Terms of \(x\)

After rewriting and differentiating (details skipped here for space), the peak condition becomes:

\[ 5(1 - e^{-x}) = x \]

This is a transcendental equation.

It cannot be solved analytically.

Step 3: Solve the Peak Equation (Numerically)

Peak condition:

\[ 5(1 - e^{-x}) = x \]

Numerical solution:

\[ x \approx 4.965 \]

This single number pins down where the Planck curve peaks.

Important

This is the calculus payoff: one equation, one number, one measurable prediction.

Step 4: Turn \(x\) into Wien’s Constant

Use the definition

\[ x = \frac{hc}{\lambda_{\rm peak} kT} \]

to get

\[ \lambda_{\rm peak} T = \frac{hc}{kx} \]

Substitute \(x \approx 4.965\):

\[ \lambda_{\rm peak} T = 2.898 \times 10^{-3}\ \mathrm{m\,K} = 2.898 \times 10^6\ \mathrm{nm\,K} \]

That constant is Wien’s displacement constant.

Tip

Why calculus matters: it generates the constant you use in real stellar temperature inference.

What This Derivation Really Means

The peak of the Planck curve is determined by a balance between two effects.

The \(\lambda^{-5}\) factor rises sharply at short wavelength.

The exponential suppression term kills short-wavelength emission.

The maximum occurs where those two competing effects balance.

The number \(4.965\) encodes that balance.

Important

Wien’s law is not empirical magic. It falls directly out of quantum thermal physics.

Long-Wavelength Limit (Rayleigh–Jeans)

When \(x = hc/(\lambda kT) \ll 1\):

\[ e^x \approx 1 + x \]

Planck reduces to:

\[ B_\lambda \propto \frac{T}{\lambda^4} \]

This matches classical physics.

Short-Wavelength Limit (Exponential Suppression)

When \(x \gg 1\):

\[ e^x - 1 \approx e^x \]

Planck becomes:

\[ B_\lambda \propto \lambda^{-5} e^{-hc/(\lambda kT)} \]

The exponential term suppresses UV emission.

Warning

This suppression is what prevents the ultraviolet catastrophe.

Why This Matters for Stellar Inference

Without Planck’s exponential cutoff:

- Total luminosity would diverge.

- Stefan-Boltzmann would not converge.

- Wien’s law would not exist.

Quantum mechanics makes stellar astrophysics possible.

ASTR 201 • Module 2, Lecture 2