Spectra & Composition

What’s It Made Of, and How Is It Moving?

February 17, 2026

Learning Objectives

- Explain Kirchhoff’s three laws and predict which spectrum a source produces

- Interpret the Bohr model to explain why spectral lines have specific wavelengths

- Classify stars by spectral type (OBAFGKM) as a temperature sequence

- Apply the Doppler shift to measure stellar radial velocities

- Connect spectral absorption to the greenhouse effect

All stars are \({\sim}73\%\) hydrogen and \({\sim}25\%\) helium.

So why do their spectra look so different?

Today’s Roadmap

- Kirchhoff’s Laws — why stars show absorption spectra

- Spectral Lines — atomic fingerprints from the Bohr model

- OBAFGKM — a temperature sequence, not composition

- Doppler Shift — reading stellar motion from light

- Putting It Together — three clues from one spectrum

- Climate Connection — same physics, different scale

Kirchhoff’s Laws

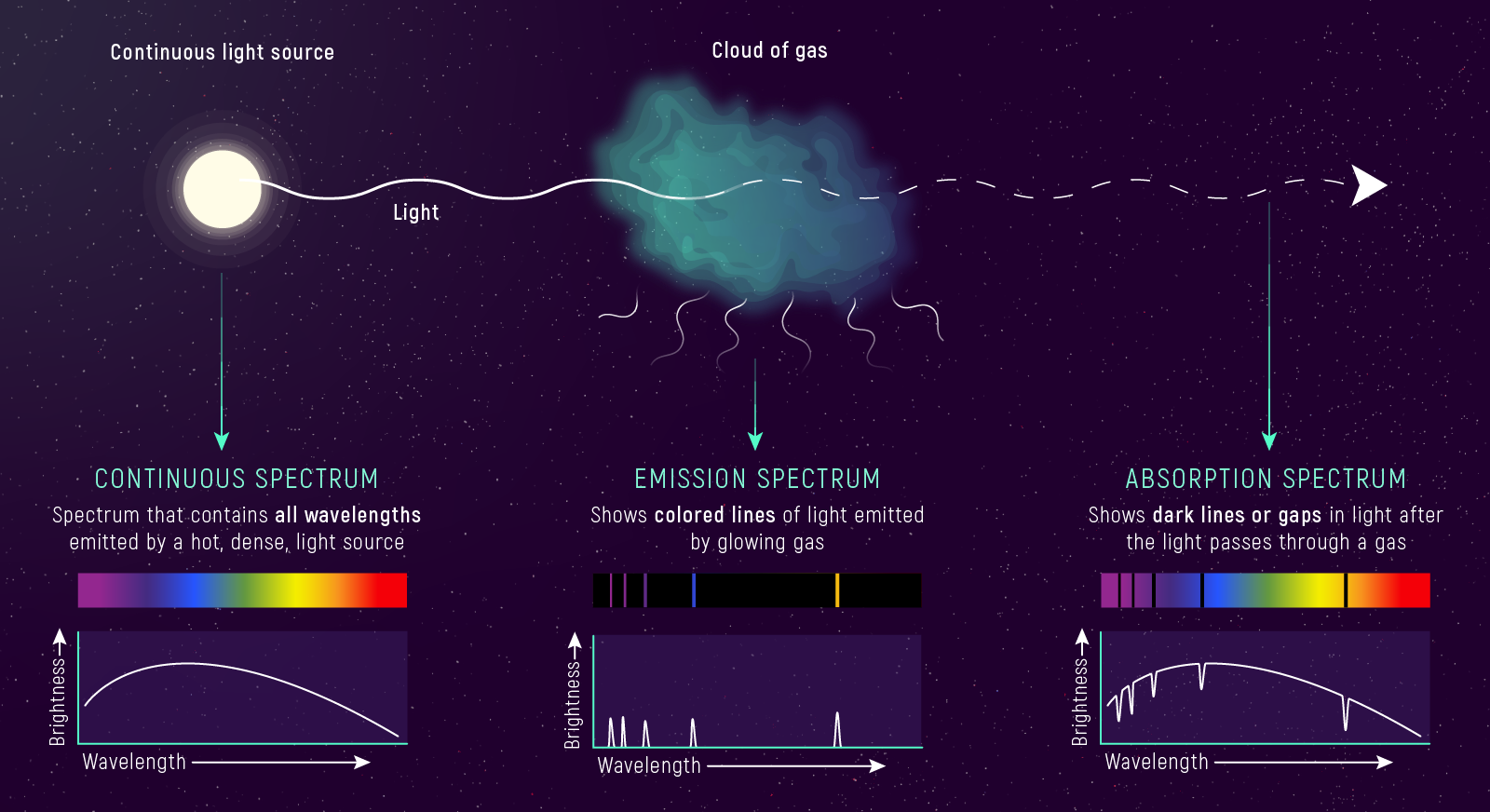

Three spectra, three physical setups

Three Types of Spectra

- Continuous — hot, dense source → all wavelengths (Planck curve)

- Emission — hot, low-density gas → bright lines on dark background

- Absorption — cooler gas in front of hot continuum → dark lines

The same gas produces emission OR absorption depending on what’s behind it.

Quick Label (30 seconds)

For each spectrum type, write down: (1) the type and (2) the physical setup in six words or fewer.

Example format:

- Continuous — hot, dense source emits all wavelengths.

- Emission — hot, thin gas emits bright lines.

- Absorption — cool gas blocks specific colors.

Kirchhoff’s Three Laws

- Hot, dense source → continuous spectrum (all wavelengths)

- Hot, low-density gas → emission lines (bright lines, dark background)

- Cooler gas in front of hot continuum → absorption lines (dark lines in rainbow)

The same gas absorbs at the same wavelengths it would emit.

The Reverse Problem

In practice, you work Kirchhoff’s laws backwards:

Given a spectrum → infer the physical configuration.

- Dark lines in a rainbow? → cooler gas in front of a hotter continuum

- Bright lines on dark background? → hot, tenuous gas, no continuum behind it

- Smooth rainbow, no lines? → hot, dense source

This is the skill you’ll use for the rest of the course.

Why Stars Show Absorption Spectra

Two-layer model:

- Photosphere (\(\tau \approx 1\)) — hot, dense → continuous spectrum (Law 1)

- Atmosphere (cooler, above) → absorbs at specific wavelengths (Law 3)

We see: a continuous rainbow with dark lines carved into it.

Temperature decreases outward — that’s why absorption, not emission.

Two Myths to Kill Now

Myth 1: “Spectral type tells me what a star is made of.”

It doesn’t — not directly. Spectral type primarily reflects temperature. Stars of wildly different types have nearly identical compositions. (Part 3 will prove this.)

Myth 2: “A redshifted star looks red.”

It doesn’t. “Redshift” means lines shift to longer wavelengths — a fractional change of \({\sim}0.01\%\). A blue O star receding from you is still blue. (Part 4 makes this quantitative.)

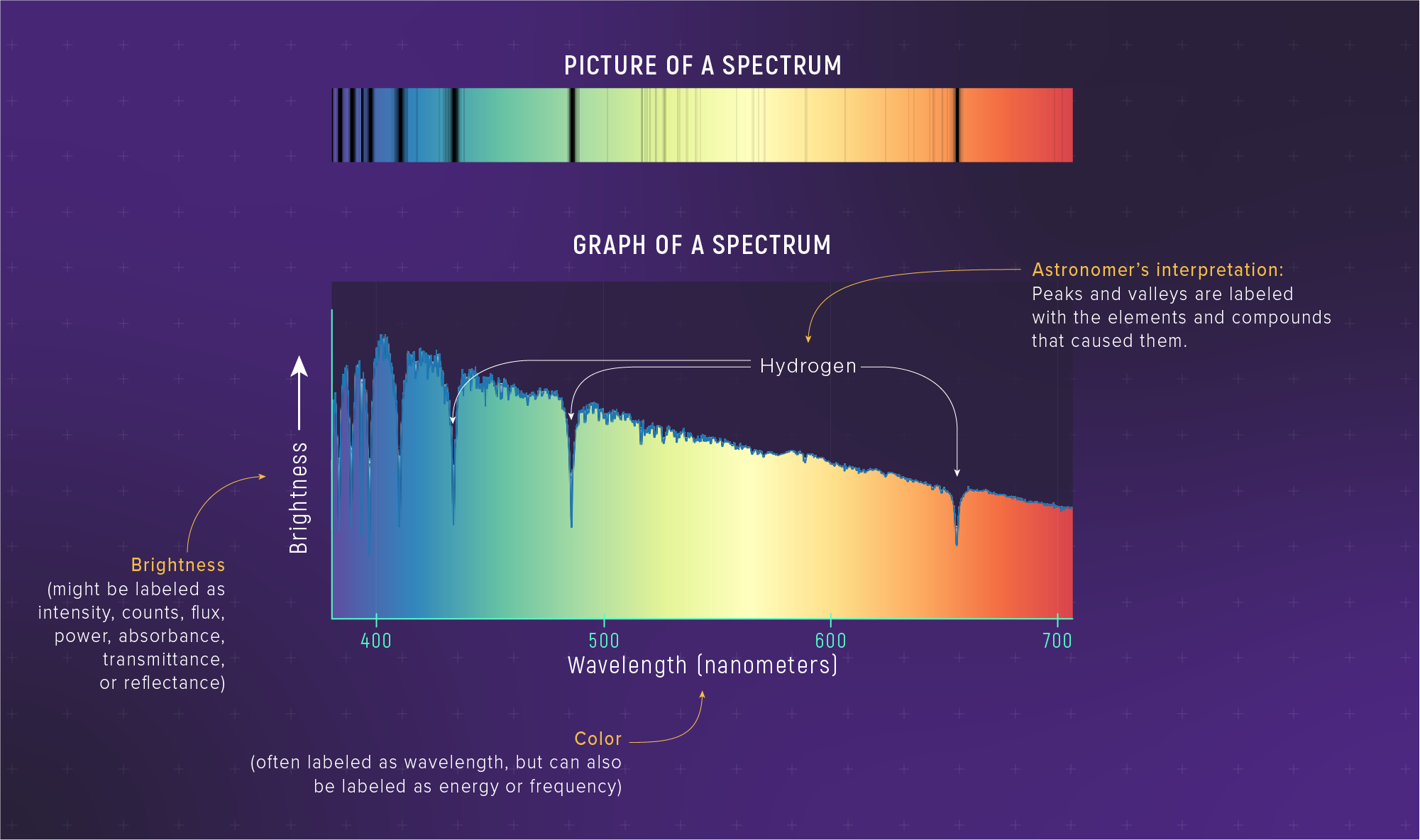

Observable → Model → Inference

- Observable: Dark lines at specific wavelengths in a stellar spectrum

- Model: Kirchhoff’s third law — cooler atmosphere absorbs from hotter photosphere

- Inference: The star has a hot interior surrounded by a cooler atmosphere

The dark lines are the key to everything that follows.

🔍 Spectrum Detective — Clue 0: The shape of the spectrum (continuous vs. lines, absorption vs. emission) tells you the physical setup of the source.

Prediction: Which Spectrum?

You look at a glowing neon sign through a spectrograph.

Commit to one answer:

Continuous spectrum — smooth rainbow

Emission spectrum — bright lines on dark background

Absorption spectrum — dark lines in a rainbow

Think–Pair–Share: Design a Kirchhoff Test

Scenario: You have a hydrogen gas tube and a bright white lamp.

- How would you set up an experiment to produce a hydrogen emission spectrum?

- How would you rearrange to produce a hydrogen absorption spectrum?

- Which Kirchhoff law governs each setup?

30 seconds alone → 1 minute with a neighbor → share out

Spectral Lines as Atomic Fingerprints

The Bohr model and discrete energy levels

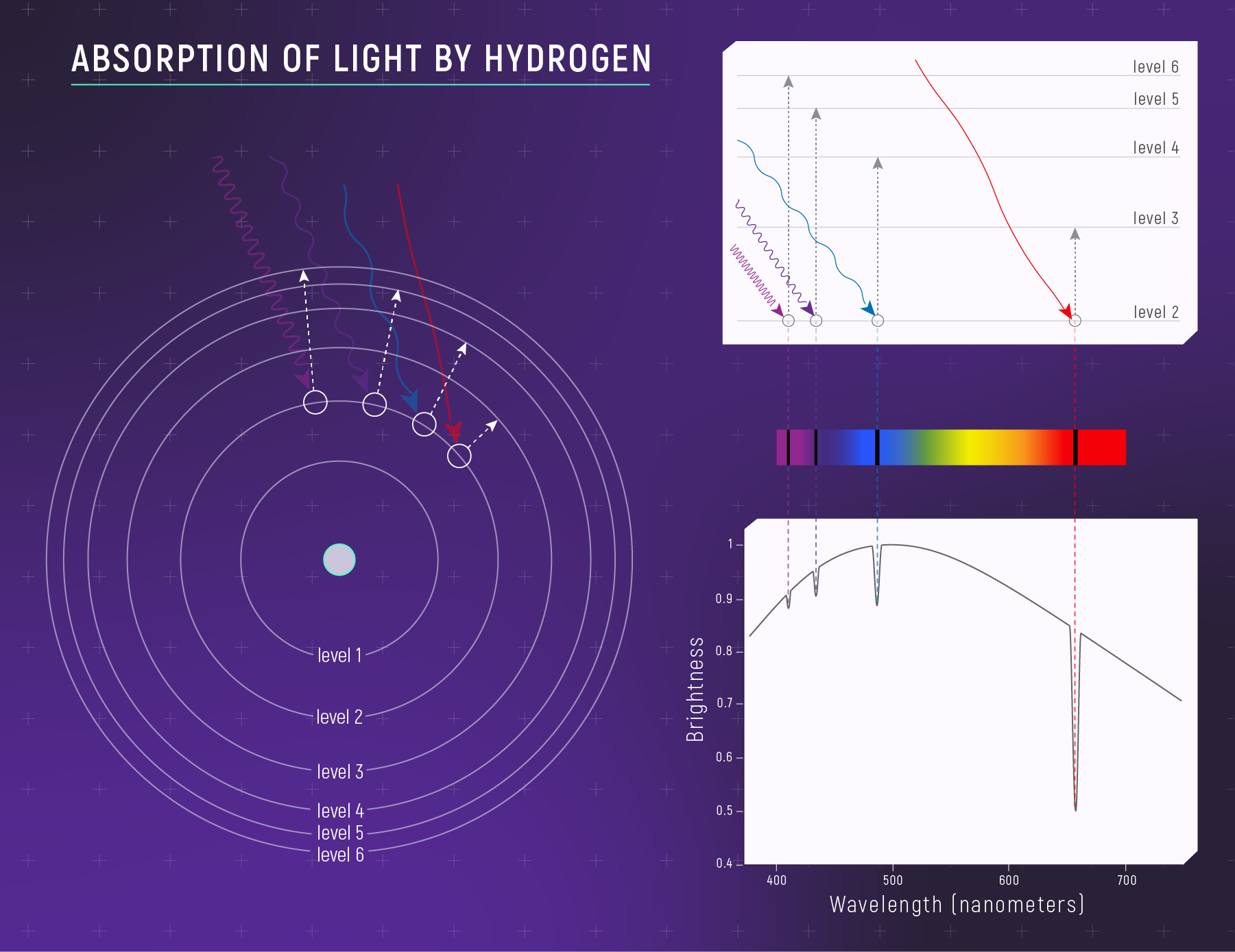

The Bohr Model: Discrete Energy Levels

Electrons occupy specific energy rungs — they cannot hover between them.

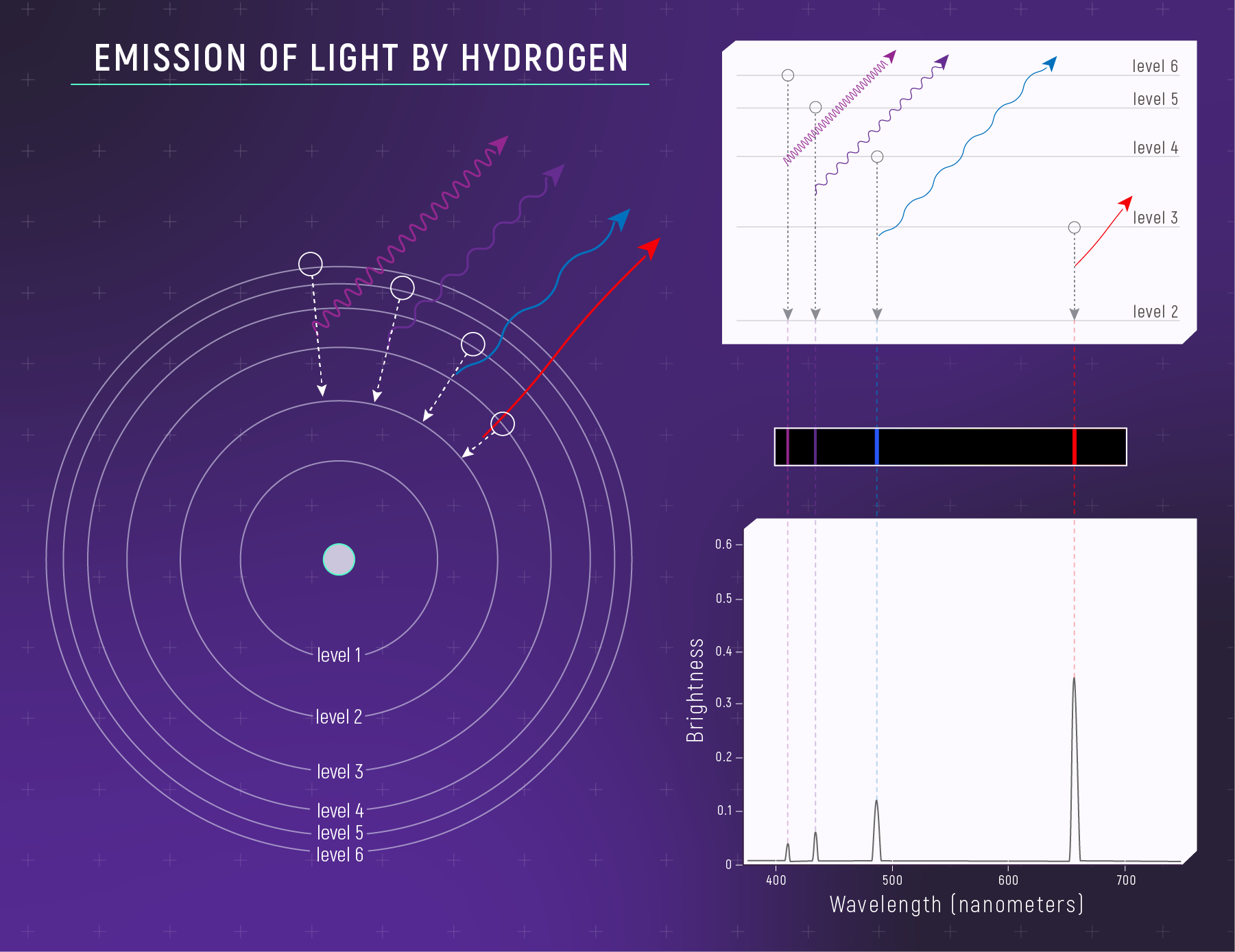

The Reverse: Emission

Same energy gaps → same wavelengths — whether absorbing or emitting.

Hydrogen Energy Levels

\[E_n = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{n^2}\]

- \(n = 1\) (ground state): \(E_1 = -13.6\ \text{eV}\) — most tightly bound

- \(n = 2\): \(E_2 = -3.4\ \text{eV}\)

- \(n \to \infty\): \(E = 0\) — electron is free (ionized)

Negative sign = the electron is bound. You must add energy to free it.

Spectral Lines Come from Transitions

When an electron jumps between levels:

\[\Delta E = |E_{\text{upper}} - E_{\text{lower}}|\]

The photon’s wavelength is set by the energy gap:

\[\lambda = \frac{hc}{\Delta E}\]

Different elements → different energy levels → different spectral lines.

The Balmer Series: Hydrogen’s Visible Fingerprint

Transitions to/from \(n = 2\):

| Transition | Name | Wavelength | Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(n = 3 \to 2\) | H\(\alpha\) | \(656\ \text{nm}\) | Deep red |

| \(n = 4 \to 2\) | H\(\beta\) | \(486\ \text{nm}\) | Blue-green |

| \(n = 5 \to 2\) | H\(\gamma\) | \(434\ \text{nm}\) | Violet |

| \(n = 6 \to 2\) | H\(\delta\) | \(410\ \text{nm}\) | Near-UV |

Energy gaps of \(\sim 1.9\text{–}3.0\ \text{eV}\) → visible wavelengths.

Worked Example: Calculating H\(\alpha\)

Problem: Predict the wavelength of \(n = 3 \to 2\) in hydrogen.

Step 1 — Energy levels: \[E_3 = \frac{-13.6\ \text{eV}}{9} = -1.51\ \text{eV} \qquad E_2 = \frac{-13.6\ \text{eV}}{4} = -3.40\ \text{eV}\]

Step 2 — Energy gap: \[\Delta E = |-1.51\ \text{eV} - (-3.40\ \text{eV})| = 1.89\ \text{eV}\]

Step 3 — CGS conversion: (\(1\ \text{eV} = 1.602 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}\)) \[\lambda = \frac{hc}{\Delta E} = \frac{1.986 \times 10^{-16}\ \text{erg·cm}}{3.03 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}} = 6.56 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{cm} = 656\ \text{nm}\ \checkmark\]

The \(hc\) Shortcut — Your Default Tool

For any transition with energy gap \(\Delta E\) (in eV):

\[\lambda\ (\text{nm}) \approx \frac{1240\ \text{eV·nm}}{\Delta E\ (\text{eV})}\]

For H\(\alpha\):

\[\lambda \approx \frac{1240\ \text{eV·nm}}{1.89\ \text{eV}} \approx 656\ \text{nm}\ \checkmark\]

Same answer, one line. Use \(hc \approx 1240\ \text{eV·nm}\) freely unless a problem asks for CGS.

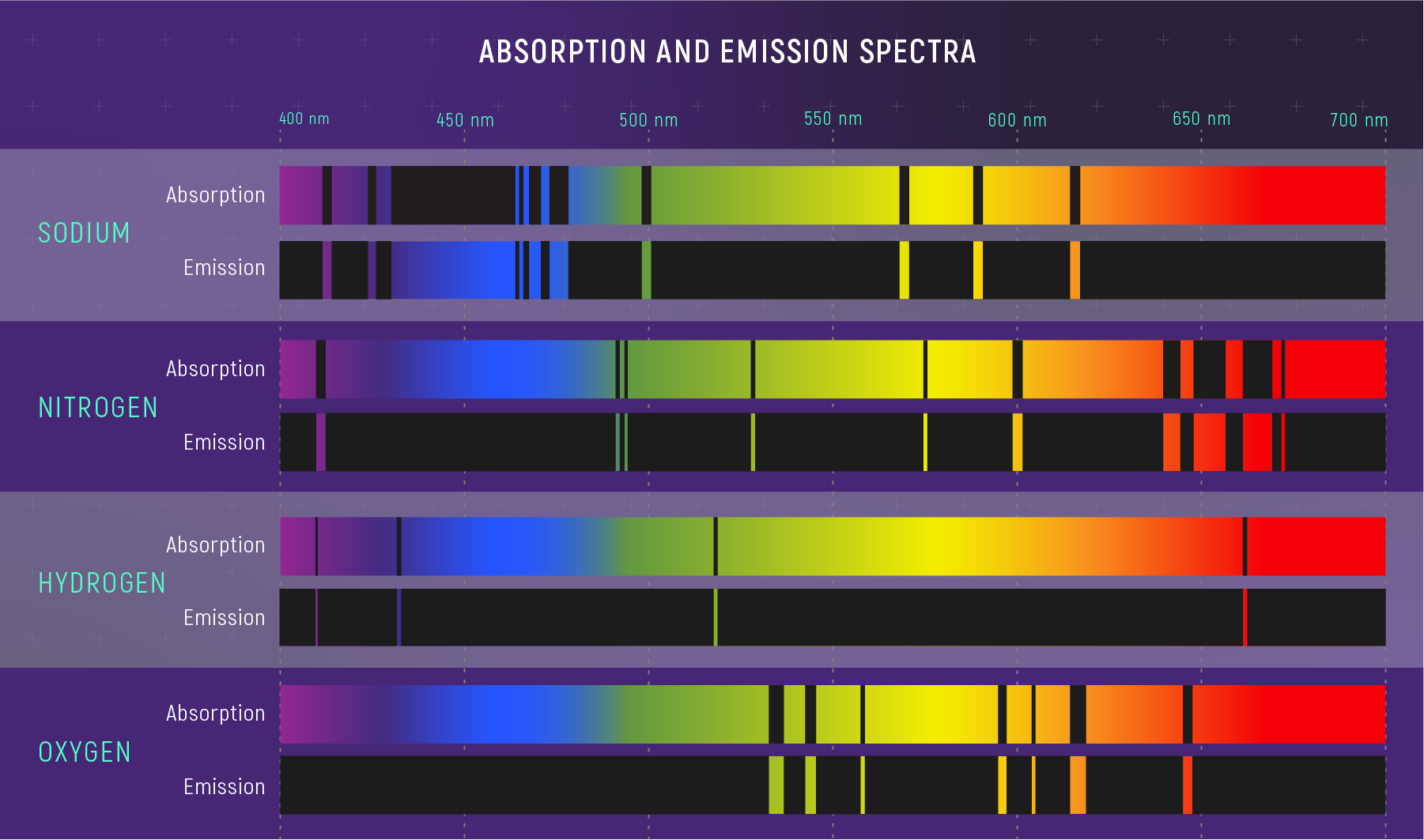

Every Element Has a Unique Barcode

Match observed lines to laboratory wavelengths → identify the element.

🔍 Spectrum Detective — Clue 1: The positions of absorption lines tell you which elements are present — each element’s fingerprint is unique.

Real Data: Altair’s Spectrum

Two tools in one observation: the curve gives temperature (Wien), the lines give composition.

Think–Pair–Share: Mystery Element

A star’s spectrum shows absorption lines at \(393.4\ \text{nm}\) and \(396.8\ \text{nm}\) — but hydrogen has no transitions at these wavelengths.

- Are these lines from hydrogen? How do you know?

- These are the Ca II H & K lines (ionized calcium). What does “ionized” tell you about the temperature?

- In which spectral type(s) would you expect these lines to be strongest?

30 seconds alone → 1 minute with a neighbor → share out

Quick Check: Spectral Lines

An absorption line appears at \(486.1\ \text{nm}\) in a star’s spectrum. Which element and transition is this?

- Helium, ground-state transition

- Hydrogen, \(n = 4 \to 2\) (H\(\beta\))

- Sodium, D-line transition

- Iron, ionized state

OBAFGKM

A temperature sequence — not composition

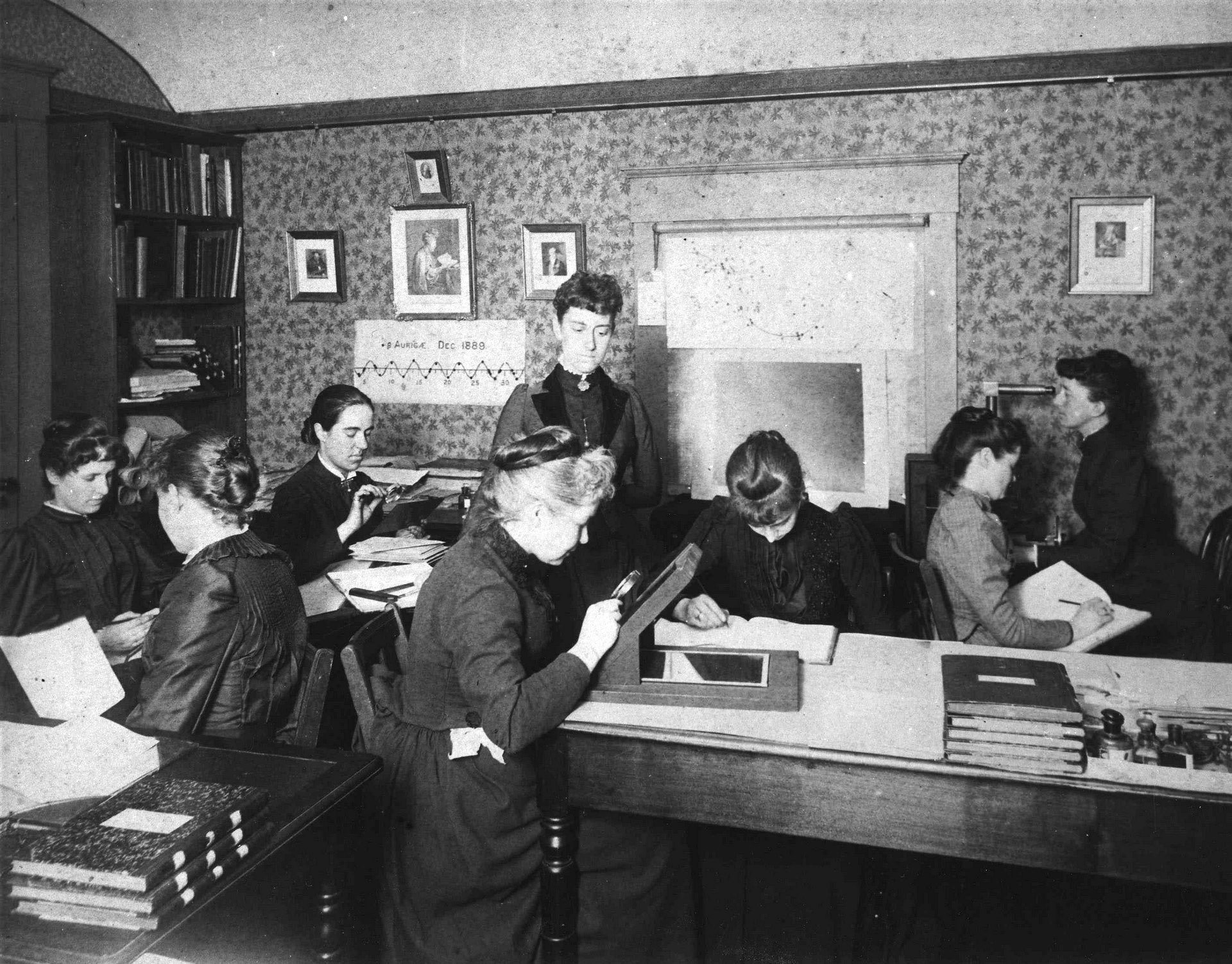

The Harvard Computers

500,000 glass plates. Millions of spectra. No automation.

- Williamina Fleming — first classification system, 310 variable stars, Horsehead Nebula

- Annie Jump Cannon — 350,000 spectra classified, OBAFGKM sequence

- Antonia Maury — noticed line widths vary → luminosity class

Hired as cheap labor (25–50¢/hr, less than secretaries), denied telescope access — and they transformed astronomy.

Data First, Theory Later

The Harvard classifications demanded explanation:

- 1925: Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin proved stars are overwhelmingly hydrogen & helium — arguably the most important PhD in astronomy. Her advisor Russell called it “clearly impossible” before later admitting she was right.

- 1920s: Eddington’s stellar models explained OBAFGKM as a temperature sequence.

- 1938: Bethe’s nuclear fusion theory completed the picture.

The pattern was observed first. The physics was built to explain it.

This is Observable → Model → Inference in its purest historical form.

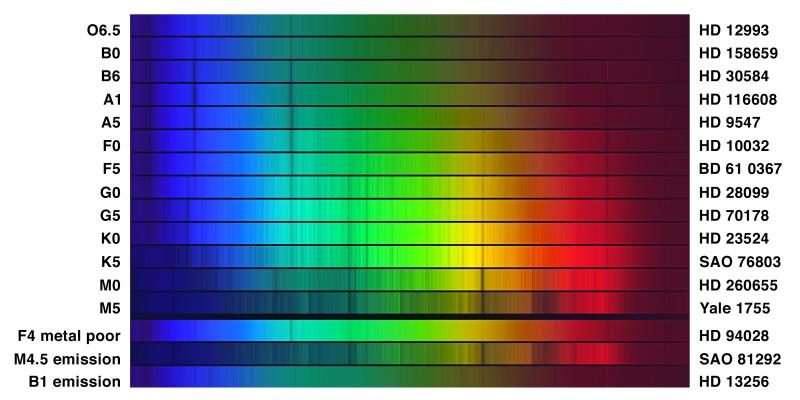

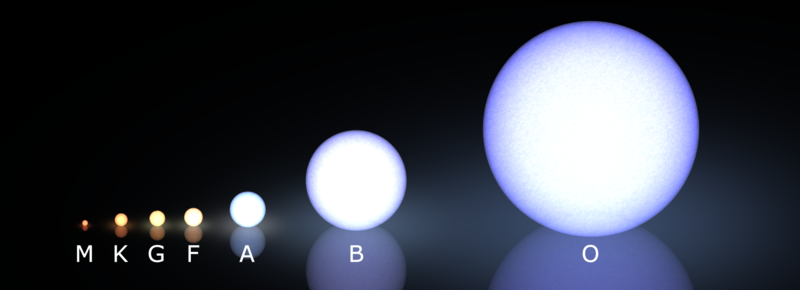

The Spectral Sequence

From top to bottom: O → B → A → F → G → K → M

- Hot (O): ionized helium lines

- Middle (A): strongest hydrogen Balmer lines

- Cool (M): molecular bands (TiO)

Spectral features change dramatically — but composition is nearly the same across all types.

Oh Be A Fine Guy/Girl, Kiss Me.

OBAFGKM at a Glance

| Type | Color | Temperature | Main-Seq. Prevalence | Dominant Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Blue-violet | \(\gtrsim 30{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(0.00003\%\) | Ionized helium |

| B | Blue-white | \(10{,}000\text{–}30{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(0.13\%\) | Neutral helium, strong H |

| A | White | \(7{,}500\text{–}10{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(0.6\%\) | Strongest H Balmer |

| F | Yellow-white | \(6{,}000\text{–}7{,}500\ \text{K}\) | \(3\%\) | Moderate H, weak metals |

| G | Yellow | \(5{,}200\text{–}6{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(7.6\%\) | Weak H, strong metals |

| K | Orange | \(3{,}700\text{–}5{,}200\ \text{K}\) | \(12.1\%\) | Very weak H, molecular bands |

| M | Red-orange | \(\lesssim 3{,}700\ \text{K}\) | \(76.5\%\) | TiO molecular bands |

M dwarfs are \(76.5\%\) of all stars — too faint to see by eye.

Four Knobs, One Spectrum

| What You Measure | What It Tells You |

|---|---|

| Line positions (which wavelengths are dark) | Composition — which elements are present |

| Line strength pattern (which species dominate) | Temperature → spectral type (OBAFGKM) |

| Line widths (narrow vs. broad) | Surface gravity / rotation → luminosity class |

| Metal line forest (amplitude relative to H) | Metallicity (heavy-element abundance) |

Temperature is the dominant knob — it controls line strengths so powerfully that it can mask composition differences entirely.

Why Temperature Controls Line Strength

- For H absorption: electron must already be in \(n = 2\)

- Fraction in \(n = 2\) depends on temperature: \(\propto e^{-\chi_2/k_BT}\)

- Too cool (M stars): almost no atoms in \(n = 2\) → weak H lines

- Just right (A stars): maximum population in \(n = 2\) → strongest H lines

- Too hot (O stars): hydrogen is ionized → no neutral H → weak H lines

Predict First: Which Type Wins?

All stars are \({\sim}73\%\) hydrogen. Hydrogen Balmer absorption requires electrons already in \(n = 2\), which is \(10.2\ \text{eV}\) above the ground state.

At which spectral type — O, A, G, or M — would you expect the strongest Balmer lines, and why?

Commit to an answer before I show you.

The Goldilocks Problem: A Balmer Line Peak

Two competing effects at work:

- Excitation (\(\propto e^{-\chi_2/k_BT}\)): hotter → more atoms in \(n = 2\)

- Ionization: hotter → more atoms lose electrons entirely

| Temperature | Excitation | Ionization | Balmer strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(3{,}000\ \text{K}\) (M) | Very low | Negligible | Weak — no \(n=2\) |

| \(10{,}000\ \text{K}\) (A) | High | Moderate | Peak — sweet spot |

| \(35{,}000\ \text{K}\) (O) | Very high | Nearly complete | Weak — no neutral H |

Balmer strength rises, peaks at A stars, then falls — a competition, not monotonic growth.

Prediction: Why Weak H Lines?

An M star (\(T \approx 3{,}000\ \text{K}\)) has weak hydrogen Balmer lines.

Which explanation is correct?

M stars have very little hydrogen

M stars are too cool — almost no H atoms in the \(n = 2\) state

M stars are so hot that hydrogen is ionized

M stars are too far away to show lines

The Spectral Sequence Is Temperature

- Do O stars have more helium? No — same composition. Temperature ionizes H and excites He.

- Do A stars have more hydrogen? No — same abundance. Temperature puts H into \(n = 2\).

- Do M stars lack hydrogen? No. Temperature keeps H atoms in \(n = 1\) (ground state).

Same atoms. Different temperatures. Different spectra.

🔍 Spectrum Detective — Clue 2: The pattern of line strengths tells you temperature (spectral type). Strong Balmer? \({\sim}10{,}000\ \text{K}\). TiO bands? Below \({\sim}3{,}700\ \text{K}\).

Quick Check: Spectral Type

Two stars have identical composition. Star X is spectral type A; Star Y is spectral type M. What’s different?

- Star X has more hydrogen

- Star Y has more metals

- Star X is hotter, so more H atoms occupy the \(n = 2\) level

- Star Y is closer, so lines appear weaker

Metallicity: A Secondary Effect

Metallicity (\(Z\)) = mass fraction of elements heavier than helium.

- Sun: \(Z_\odot \approx 0.014\) — about \(1.4\%\) “metals”

- High-\(Z\) stars: more and stronger metal absorption lines

- Low-\(Z\) stars: “cleaner” spectra with fewer metal lines

But metallicity is second-order for classification. Two stars at the same temperature with different \(Z\) have the same spectral type — the metal line strengths differ, but which species dominates is set by temperature.

Beyond Temperature: What Line Widths Reveal

- Giants/supergiants: low-density atmospheres → narrow spectral lines

- Dwarfs (main-sequence): compact, dense atmospheres → broad spectral lines

G2V (Sun) and G2Ib (supergiant): same temperature, wildly different size and luminosity.

The Doppler Shift

Reading stellar motion from light

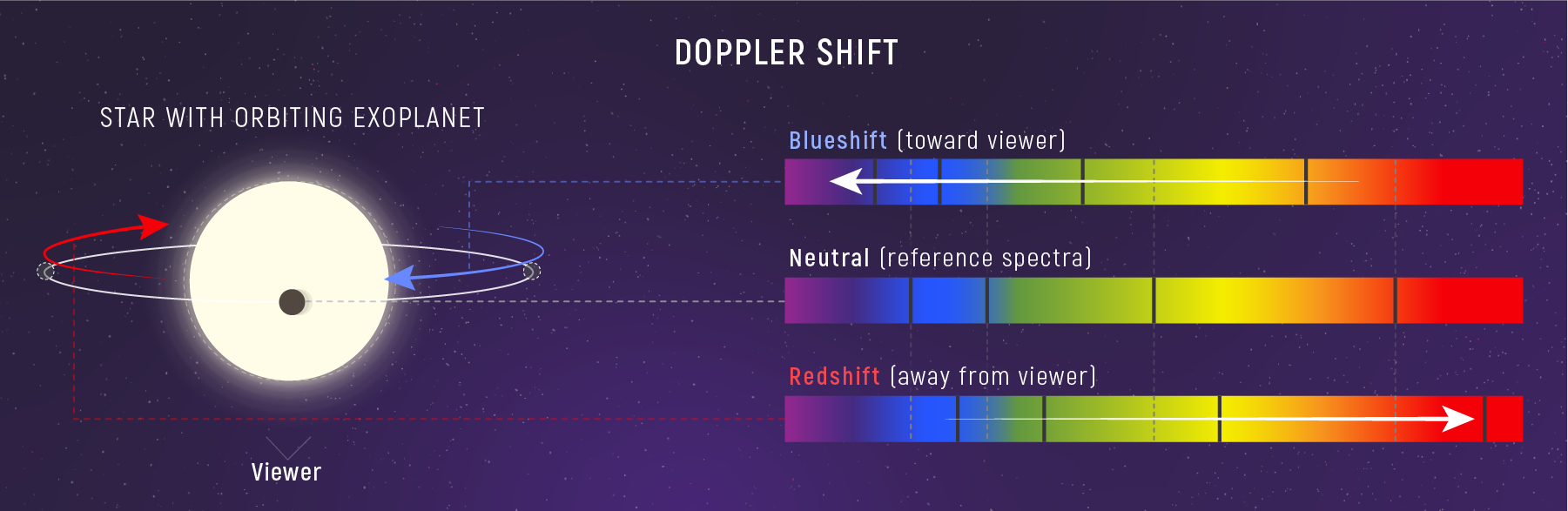

Doppler: Wavelength Shifts from Motion

Motion along the line of sight shifts all spectral lines:

- Receding → lines shift to longer wavelengths (redshift)

- Approaching → lines shift to shorter wavelengths (blueshift)

Typical stellar velocities: \(10\text{–}100\ \text{km/s}\) → shifts of only \({\sim}0.01\text{–}0.03\%\), but measurable.

The Doppler Formula

\[\frac{\Delta\lambda}{\lambda_0} = \frac{v_r}{c}\]

- \(\Delta\lambda = \lambda_{\text{obs}} - \lambda_0\) — the shift

- \(v_r\) — radial velocity (+ = receding, − = approaching)

- \(c = 3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}\) — speed of light

Redshift (\(\Delta\lambda > 0\)): source receding | Blueshift (\(\Delta\lambda < 0\)): source approaching

Diagnostic: A real Doppler shift moves all lines by the same fraction \(\Delta\lambda/\lambda_0\). If only one line shifts — it’s a misidentification, not motion.

Worked Example: Radial Velocity from H\(\alpha\)

Problem: H\(\alpha\) observed at \(656.5\ \text{nm}\) (rest: \(656.3\ \text{nm}\)). Approaching or receding?

Step 1 — Direction: \(\lambda_{\text{obs}} > \lambda_0\) → redshifted → receding

Step 2 — Shift: \(\Delta\lambda = 656.5\ \text{nm} - 656.3\ \text{nm} = 0.2\ \text{nm}\)

Step 3 — Velocity: \[v_r = c \times \frac{\Delta\lambda}{\lambda_0} = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times \frac{0.2\ \text{nm}}{656.3\ \text{nm}} \approx 91\ \text{km/s}\]

A \(0.03\%\) shift → \({\sim}91\ \text{km/s}\). Tiny shift, huge velocity.

Quick Check: Doppler Direction

H\(\beta\) (rest: \(486.1\ \text{nm}\)) is observed at \(485.9\ \text{nm}\). The star is…

- Approaching (blueshifted — observed wavelength is shorter)

- Receding (redshifted)

- Stationary (no shift)

- Rotating (broadened)

The Doppler Wobble in Action

Think–Pair–Share: Exoplanet Wobble

A star’s H\(\alpha\) line oscillates between \(656.25\ \text{nm}\) and \(656.35\ \text{nm}\) over a 4-day cycle. The rest wavelength is \(656.3\ \text{nm}\).

- Is the star moving? How do you know?

- What is the velocity amplitude (\(v_r\)) of the wobble?

- What could cause a periodic Doppler oscillation?

30 seconds alone → 1 minute with a neighbor → share out

Doppler Unlocks Masses

If a star is in a binary system, its radial velocity oscillates as it orbits.

Measure the oscillation period and amplitude → infer the companion’s mass.

Lecture 4: Binary orbits + Doppler → stellar masses.

🔍 Spectrum Detective — Clue 3: The shifts of line positions — every line offset by the same fraction — tell you the star’s radial velocity.

Putting It Together

Three clues from one spectrum

One Spectrum, Four Inferences

| Observable | What we measure | What we infer |

|---|---|---|

| Line positions (which wavelengths are dark) | Wavelengths matched to lab data | Composition |

| Line strength pattern (which species dominate) | Relative strengths | Temperature → spectral type |

| Line shifts (offset from lab wavelengths) | Doppler shift \(\Delta\lambda/\lambda_0\) | Radial velocity |

| Line widths (narrow vs. broad) | Pressure/rotational broadening | Surface gravity → luminosity class |

Composition, temperature, motion, and size — from a single observation.

🔍 Spectrum Detective — Case Closed. All clues collected: composition (Clue 1), temperature (Clue 2), velocity (Clue 3). Three independent measurements, one observation.

Multi-Clue Diagnosis

Observed: \(T \approx 9{,}500\ \text{K}\), strong Balmer lines, weak metals, H\(\alpha\) at \(656.1\ \text{nm}\)

(a) Spectral type: \({\sim}9{,}500\ \text{K}\) + strong Balmer → type A

(b) Velocity: \(\Delta\lambda = 656.1\ \text{nm} - 656.3\ \text{nm} = -0.2\ \text{nm}\) → blueshifted → approaching \[v_r = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times \frac{-0.2\ \text{nm}}{656.3\ \text{nm}} \approx -91\ \text{km/s}\]

(c) What else do we need? Distance → luminosity → radius. Time-series Doppler → mass.

Try It Tonight: Read a Real Spectrum

Open the SDSS SkyServer Quick Look.

Enter: Plate 285, MJD 51930, Fiber 164 (a classic A star).

- Continuum shape — does it rise toward blue or red?

- Absorption lines — can you spot H\(\alpha\) (\(656\ \text{nm}\)) and H\(\beta\) (\(486\ \text{nm}\))?

- Line shifts — are lines at rest wavelengths, or offset?

You’ve just done real spectroscopy. Every line encodes the same physics from Parts 1–4.

The Module 2 Inference Chain

| Lecture | New Tool | What It Unlocks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parallax → distance | Distance, then luminosity |

| 2 | Color → temperature; Stefan-Boltzmann | Radius |

| 3 | Spectral lines | Composition, refined \(T\), velocity |

| 4 | Binary orbits + Doppler | Mass |

| 5–6 | Magnitudes + HR diagram | Full classification |

Five properties from photons alone. Mass needs one more tool.

Spectroscopy Meets Climate

Same physics, different scale

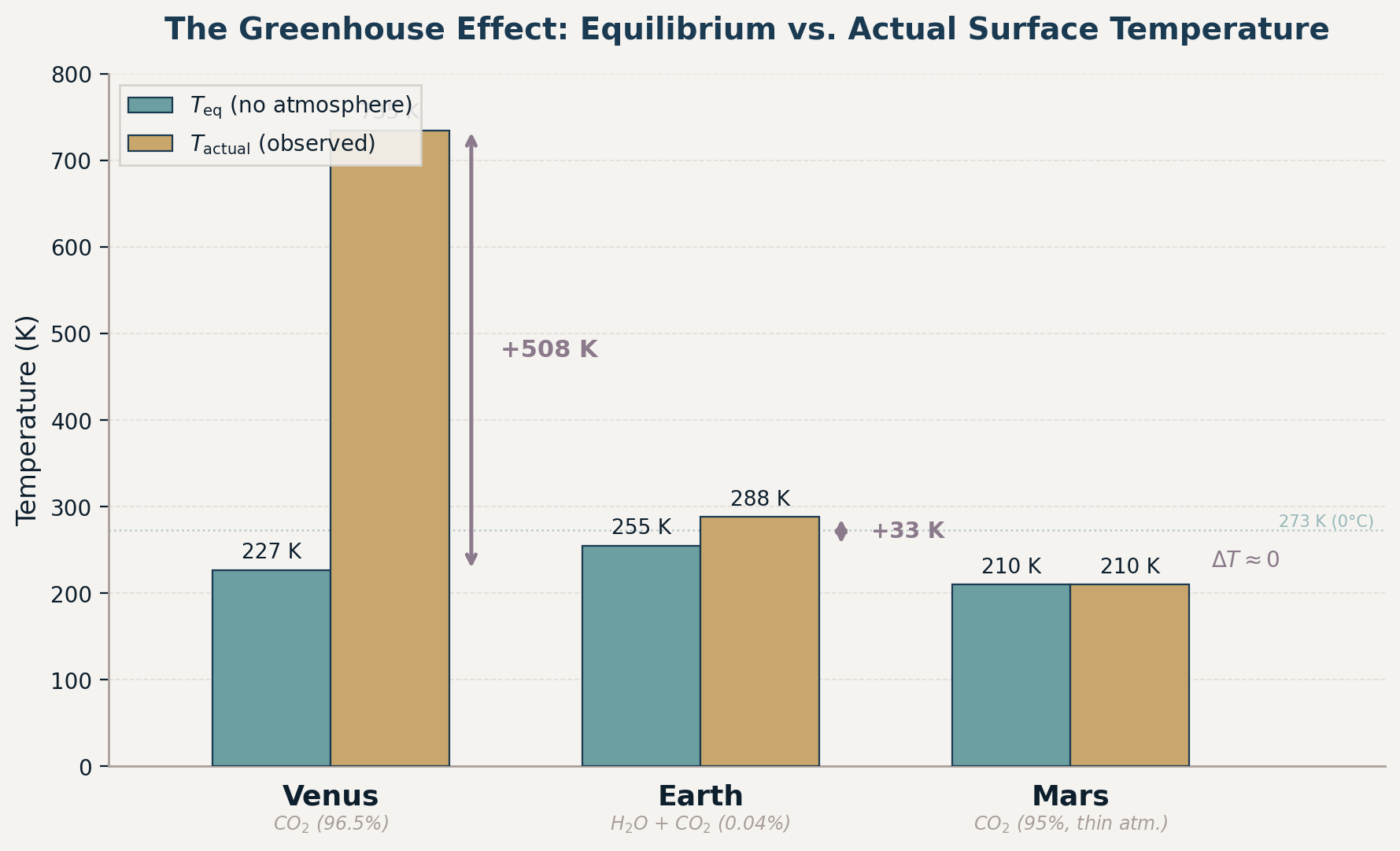

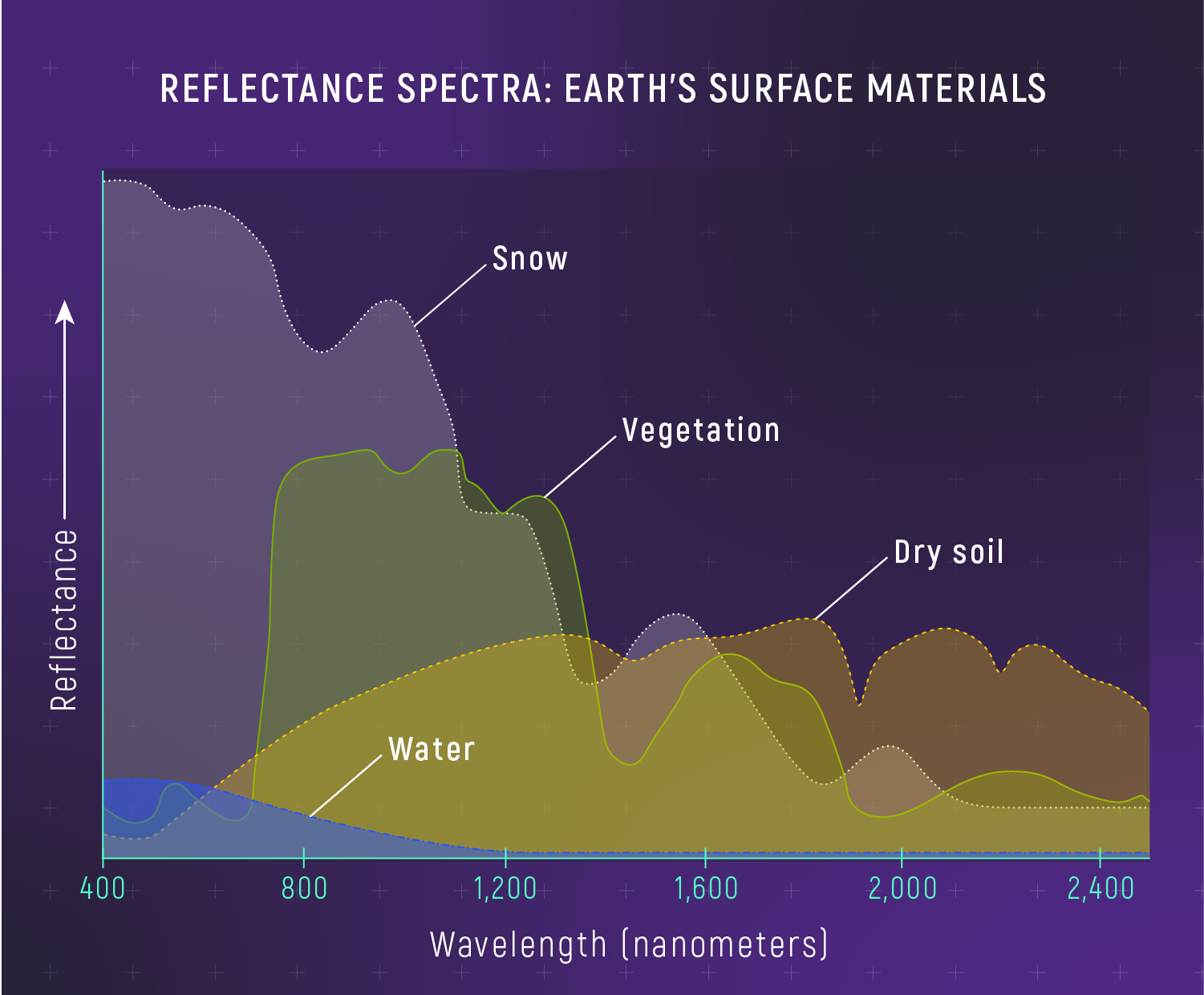

Planetary Energy Balance

At equilibrium: power absorbed from star = power radiated by planet.

\[T_{\text{eq}} = 279\ \text{K} \times (1-A)^{1/4} \times \left(\frac{d}{1\ \text{AU}}\right)^{-1/2}\]

For Earth (\(A = 0.3\), \(d = 1\ \text{AU}\)):

\[T_{\text{eq}} = 279\ \text{K} \times (0.70)^{1/4} \times 1 = 279\ \text{K} \times 0.915 = 255\ \text{K} = -18°\text{C}\]

Earth’s actual average: \(288\ \text{K} = +15°\text{C}\). Something warms us by \(33\ \text{K}\).

Predict First: What Warms Earth?

Earth’s equilibrium temperature is \(255\ \text{K}\) — well below freezing.

The observed average is \(288\ \text{K}\) — above freezing.

What must the atmosphere be doing to account for that \(33\ \text{K}\) difference?

Think about Kirchhoff’s third law applied to a planet instead of a star.

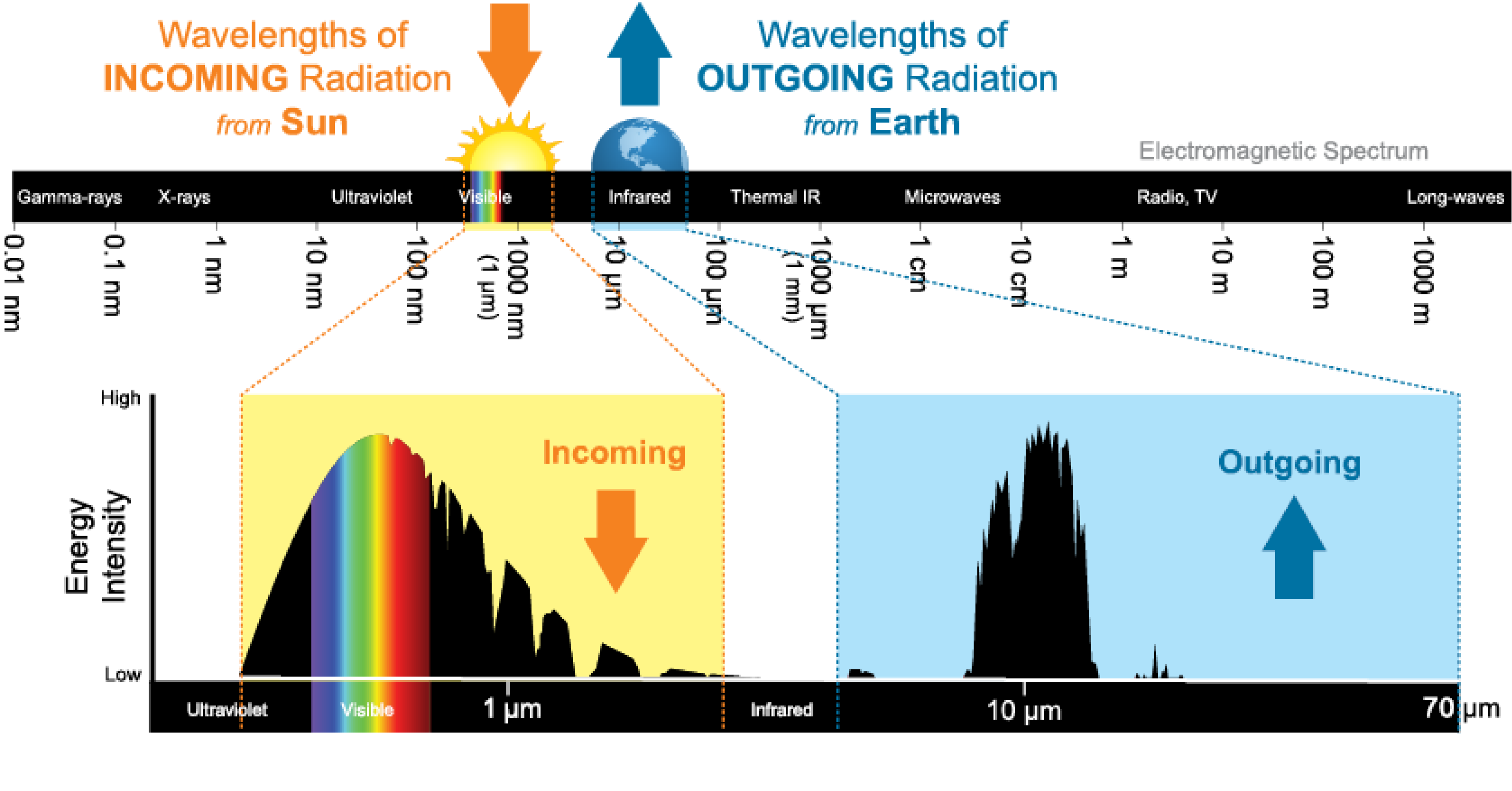

The Greenhouse Effect: Kirchhoff’s Law 3 for Planets

Two Planck curves:

- Sun → Earth peaks at ~0.5 μm (visible) — passes through atmosphere

- Earth → space peaks at ~10 μm (IR) — blocked by greenhouse gases

CO\(_2\), H\(_2\)O, CH\(_4\) absorb outgoing IR and re-emit some back down → surface warms.

This IS Kirchhoff’s Law 3: atmosphere = “cool gas” absorbing from the “hot continuum” (Earth’s surface).

A Tale of Three Planets

| Planet | \(T_{\text{eq}}\) (K) | Actual \(T\) (K) | Greenhouse warming |

|---|---|---|---|

| Venus | \(227\) | \(735\) | \(+508\ \text{K}\) |

| Earth | \(255\) | \(288\) | \(+33\ \text{K}\) |

| Mars | \(210\) | \(210\) | \({\sim}0\ \text{K}\) |

Same star, similar compositions. Atmosphere thickness makes all the difference.

CO\(_2\)’s 15 \(\mu\text{m}\) Band

CO\(_2\) absorbs at 15 \(\mu\text{m}\) — right where Earth’s thermal radiation peaks.

Try It: Mars’s Equilibrium Temperature

Mars: \(d = 1.52\ \text{AU}\), \(A = 0.25\)

\[T_{\text{eq}} = 279\ \text{K} \times (1-0.25)^{1/4} \times \left(\frac{1.52\ \text{AU}}{1\ \text{AU}}\right)^{-1/2}\]

\((0.75)^{1/4} \approx 0.930 \qquad (1.52)^{-1/2} \approx 0.811\)

\[T_{\text{eq}} \approx 279\ \text{K} \times 0.930 \times 0.811 \approx 210\ \text{K}\]

Mars’s actual surface temperature is \({\sim}210\ \text{K}\). \(T_{\text{eq}} \approx T_{\text{surface}}\) — the greenhouse effect is negligible. Why? CO\(_2\) dominates (\(95\%\)), but the atmosphere is only \(0.6\%\) of Earth’s pressure. Too thin to trap significant IR.

Quick Check: Greenhouse Physics

The greenhouse effect warms Earth because…

- CO\(_2\) absorbs incoming visible sunlight

- The ozone layer traps heat

- Atmospheric gases absorb outgoing infrared radiation and re-emit some downward

- Earth’s core heats the surface

Two More Confusions to Clear Up

- “Stronger lines = more of that element.” Not necessarily. Line strength depends primarily on temperature — which levels are populated — not abundance. An A star doesn’t have more hydrogen than an M star; it just has the right \(T\) to populate \(n = 2\).

- “Absorption lines make a star dimmer.” Negligibly. Absorbed photons are re-emitted in random directions (resonant scattering). Total luminosity is conserved; the spectrum just has narrow dark features carved into it.

(Recall: we killed Myths 1 and 2 — spectral type ≠ composition, and redshift ≠ red star — at the start.)

What Spectra Can’t Tell Us (Directly)

- Mass — need binary orbits + Doppler (Lecture 4)

- Distance — need parallax or other distance indicator (Lecture 1)

- Age — need stellar evolution models (Module 3)

- Tangential velocity — Doppler gives only the radial component

Spectra are powerful — but not omnipotent. Every tool has limits.

Summary: Key Takeaways

- Kirchhoff’s laws connect spectral appearance to physical conditions — stars show absorption spectra because of their temperature gradient

- Spectral lines are atomic fingerprints — energy levels set wavelengths

- OBAFGKM is a temperature sequence — same composition, different excitation

- Doppler shift converts wavelength shifts to velocities — \(\Delta\lambda/\lambda_0 = v_r/c\)

- Greenhouse effect is Kirchhoff’s law 3 applied to planets — same physics, different scale

The Takeaway

If you forget everything else from today, remember this:

One spectrum → composition, temperature, velocity.

A star’s light is an autobiography — if you know how to read it.

Next Time: Binary Stars & Stellar Masses

Lecture 4: We put the Doppler shift to work on binary stars.

- Radial velocity oscillations → orbital period + amplitude

- Kepler’s laws → stellar masses

- Mass is the property that determines a star’s entire life story

The last fundamental property — and the most important one.

Questions?

Common questions at this point:

- “How do we know the lab wavelengths are right?” — Measured precisely since 1859

- “Can we determine composition from just one line?” — Need multiple lines for confidence

- “Do all stars have absorption spectra?” — Most, but emission-line stars exist (Be stars, Wolf-Rayet)

ASTR 201 • Lecture 3 • Spectra & Composition