Lecture 1: Spoiler Alerts — The Universe Is Weird

How Do We Know What We Know?

Learning Objectives

By the end of this lecture, you will be able to:

- State the course thesis in one sentence: pretty pictures → measurements → models → inferences

- Explain why astronomy is fundamentally about inferring physical reality from constrained measurements

- Name the key physical quantities astronomers care about: distance, time, speed, mass, energy/luminosity, temperature

- Explain why the finite speed of light makes astronomy a “lookback time” science

- Give a one-sentence reason why wavelength matters: different wavelengths reveal different physics

This reading is designed to prime your brain, not test it. You will encounter many terms, images, and equations before you fully understand them—and that is intentional. Every technical term introduced here will be revisited later, slowly and carefully, when it actually matters.

For now, your only job is pattern recognition: notice how astronomers move from what we measure to what we infer, and how physics makes that step legitimate. Understanding will come later; recognition comes first.

Think of this reading as a movie trailer: you’ll see flashes of ideas, characters, and conflicts that won’t make full sense until you’ve seen the whole film. The semester is the movie. Today, we’re just building anticipation.

Spoiler Alerts: The Universe Is Weird (How Do We Know?)

“The cosmos is within us. We are made of star-stuff. We are a way for the universe to know itself.”

— Carl Sagan

The iron in your blood was forged in a star that exploded before our Sun was born. The calcium in your bones came from a different dying star. The oxygen you’re breathing right now was manufactured in the core of a massive star and scattered into space when that star died. You are, quite literally, made of stellar debris.

This course is about how we know that — and what else we can learn by carefully decoding the light that reaches us from across the cosmos.

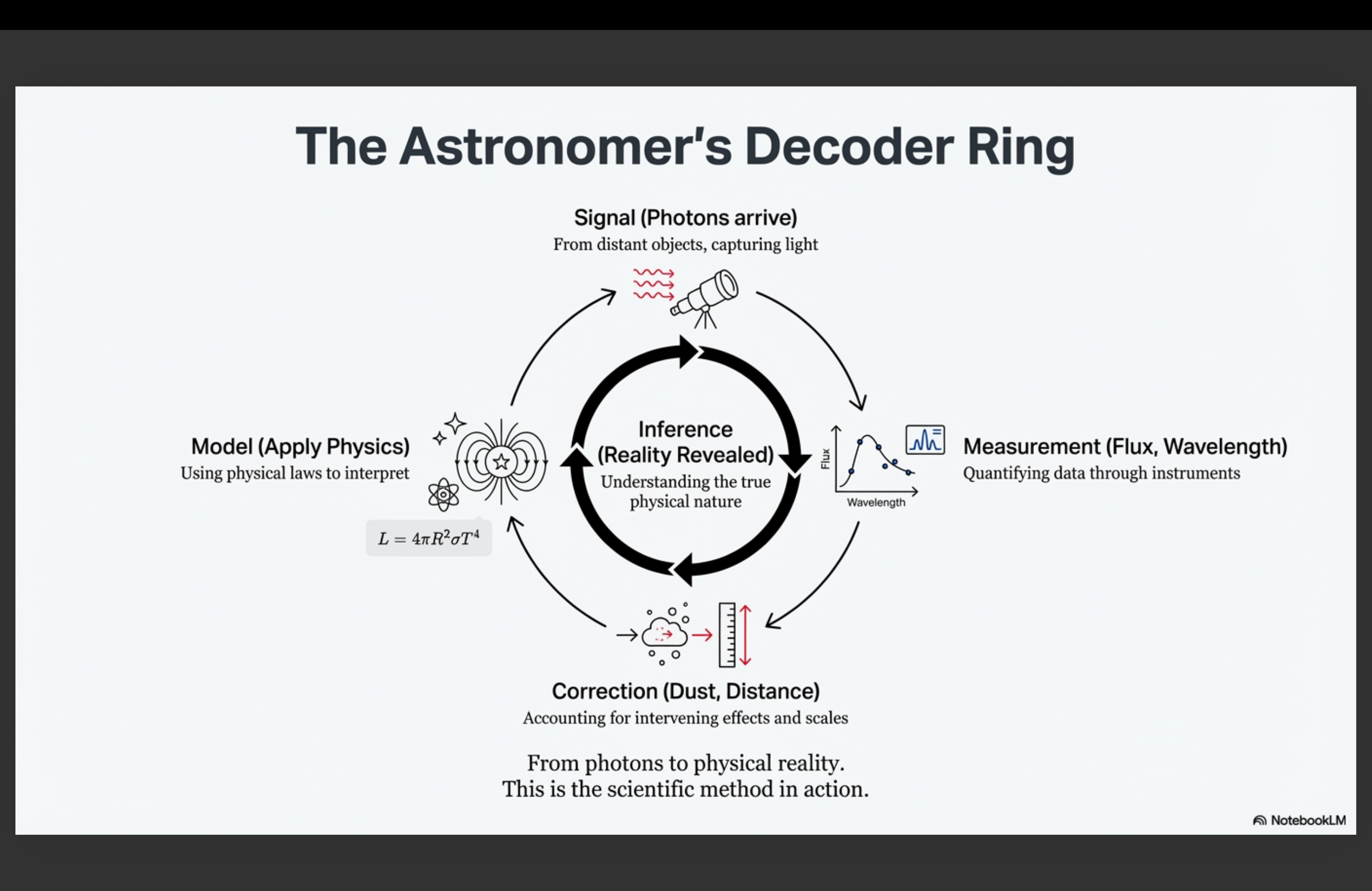

What to notice: Three questions drive modern astronomy—and we answer all of them using the same method: inference from signals. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

This first lecture sets up the conceptual framework for everything that follows. We’re going to do something unusual: spoilers first.

Section 1.1 — The Course Thesis: You’ll learn what this course is really about — not memorizing space facts, but learning how scientists extract physical understanding from limited information.

Section 1.2 — The Spoiler Reel: We’ll tour the universe through stunning images, with a twist: for each image, we ask what do we measure, what do we infer, and what physics makes that legal? You’re not expected to understand everything—that’s what the semester is for.

Section 1.3 — The Decoder Ring: You’ll see the method that transforms astronomy from stamp collecting into physics.

Section 1.4 — Light: The Cosmic Messenger: We’ll meet light itself—the only messenger that carries information across cosmic distances—and learn why its speed and wavelength matter so much.

Section 1.5 — Looking Back in Time: The lecture closes with a mind-bending consequence of light’s finite speed: looking far away means looking into the past.

Fair Warning: This semester will include equations, mathematical reasoning, and ideas that seem counterintuitive at first. Some of it will feel hard. That’s okay—that’s how learning works. By the end, you’ll have earned the right to make claims about objects billions of light-years away that you can never touch. Trust me: it’s worth it.

1.1 What This Course Is Really About

Inference: Drawing conclusions about quantities we cannot directly access (like a star’s temperature) from quantities we can measure (like its color). Inference requires a model—a physical relationship connecting observable to unobservable.

Observable: A quantity that can be directly measured—brightness, position, wavelength. Astronomers have remarkably few types of observables; nearly everything else is inferred.

Let me be direct about what this course is—and isn’t.

This course is NOT:

- Memorizing how many moons each planet has

- Identifying constellations

- Space trivia and fun facts

- Looking at pretty pictures and saying “wow, cool”

- Astro 101 with some equations sprinkled on top

You might have taken courses that focused on what’s out there—planet facts, constellation names, cosmic catalogs. Those courses build wonder and familiarity, and they’re valuable. But this course asks a fundamentally different question.

This course IS:

- How do we know what we claim to know?

- What can we actually measure from billions of kilometers away?

- How do physics and math turn limited measurements into profound understanding?

- Why should we believe any of these cosmic claims?

This is astronomy as a quantitative science. There will be equations. There will be calculations. There will be moments when your intuition fails and the math reveals something surprising. That’s not a bug—that’s the feature.

Think about this: every piece of information you’ve ever heard about the cosmos—the Sun’s temperature, the age of the universe, the composition of a distant star—none of it came from collecting samples. We can’t scoop up a piece of a star. We can’t fly to the edge of the universe with a tape measure. We’re stuck here on Earth (mostly), looking up at points of light.

And yet, somehow, we know that: - The Sun’s surface temperature is about 5,800 K - The nearest star is 4.2 light-years away - Stars are mostly hydrogen and helium - The universe is about 13.8 billion years old and expanding

How is any of that possible?

The answer is the thesis of this course:

Pretty pictures → measurements → models → inferences

Every gorgeous astronomical image you’ve ever seen is actually a dataset. The colors, the shapes, the bright spots and dark lanes—all of it encodes physical information. The job of an astronomer is to decode that information using physics and mathematics.

Pretty pictures are data. Astronomical images are built from photon counts, not snapshots. Colors are often assigned to make invisible wavelengths visible to human eyes.

The Four Things We Can Actually Measure

Here’s the humbling truth that makes astronomy both challenging and beautiful: from our cosmic vantage point, staring at points of light billions of kilometers away, we can directly measure only four types of things.

Reading tip: Treat the tables in this reading as reference maps—don’t memorize them. You’ll revisit each one when it matters.

| What We Measure | What It Means | What It Tells Us |

|---|---|---|

| Brightness | How much light energy arrives at our detector | How luminous is this, combined with how far away? |

| Position | Where the object appears on the sky (and how that changes) | Geometry, motion, orbits |

| Wavelength | Which “colors” of light are present, and in what amounts | Temperature, composition, motion toward/away from us |

| Timing | When things happen and how the above change over time | Variability, periods, dynamical timescales |

That’s it. Four types of measurements. Everything else is inferred.

What to notice: From billions of kilometers away, we can directly measure only four things. Everything else—mass, radius, temperature, age—is a calculation. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

Let’s sharpen what each one means:

Brightness is the rate at which light energy arrives at your detector—photons per second per unit area. We literally count photons. This is the raw signal, and it depends on two things we can’t disentangle from brightness alone: how luminous the source truly is, and how far away it is. A dim nearby candle and a brilliant distant lighthouse can appear equally bright.

Position is where an object appears on the sky, measured in angles. This is purely geometric—we’re mapping locations on a celestial sphere. But position becomes powerful when we track changes: the annual wobble from Earth’s orbit (parallax), the slow drift across the sky (proper motion), or the periodic wobble caused by an unseen companion.

Wavelength is the key to spectroscopy. By spreading light into its component wavelengths, we transform a single brightness measurement into thousands of data points—brightness as a function of wavelength. This spectral information encodes temperature (through the overall color), composition (through absorption and emission lines), and motion (through Doppler shifts).

Timing is special: it’s both a measurement in its own right (when did this pulse arrive?) and a way to extract additional information from the other three. A star whose brightness varies periodically tells us something a constant star doesn’t. An object whose position shifts tells us about motion. Timing transforms static snapshots into dynamic movies.

Key insight: Timing unlocks physics that static measurements miss. Variability reveals masses (through orbits), sizes (through eclipses), and internal structure (through pulsations).

A star appears to wobble periodically in its position on the sky. Which of the four observables is this, and what might we infer from it?

(Think first… then check: This is Position (tracked over time via Timing). We might infer the star has an unseen companion—a planet or another star—whose gravitational pull causes the wobble.)

What’s NOT on This List

Notice what you cannot directly measure:

| Property | How We Infer It |

|---|---|

| Temperature | From color/spectrum (hotter = bluer peak) |

| Composition | From spectral absorption/emission lines |

| Distance | From parallax, brightness + known luminosity, or other methods |

| Luminosity | From brightness + distance |

| Mass | From orbital motion (gravity reveals mass) |

| Size (radius) | From luminosity + temperature, or from eclipses |

| Age | From stellar evolution models |

Every single one of these fundamental properties must be inferred by combining measurements with physical models. The gap between “what we measure” and “what we want to know” is bridged by physics. That bridge takes the form of models—mathematical relationships that connect observables to physical quantities. We’ll formalize this in Section 1.3.

A student claims: “Astronomers measured the temperature of that star to be 5,800 K.” Is this statement technically accurate? If not, what did astronomers actually measure, and how did they get from that measurement to temperature?

(Think first… then check: The statement is imprecise. Astronomers measured the star’s spectrum or color (wavelength distribution). They inferred temperature using the physical relationship between temperature and peak emission wavelength—hotter objects emit bluer light. Temperature is never directly measured; it’s always inferred from wavelength observations via a model.)

A Taste of What “Decoding” Means

Here’s a concrete example of the decoder ring in action:

Suppose you observe two stars of the same type (same intrinsic properties), but one appears 4× fainter than the other. Why might that be?

If they’re truly identical, the fainter one must be farther away. But how much farther? This is where physics enters. Light spreads out as it travels, and the amount of light you receive decreases with the square of the distance. So if Star B is 4× fainter than Star A, Star B must be 2× farther away (because \(2^2 = 4\)).

That’s one measurement (relative brightness), one physical law (the inverse-square law), one inference (relative distance). This is what “decoding” means.

A third star of the same type appears 9× fainter than the reference star. How much farther away is it?

(Think first… then check: 3× farther, because \(3^2 = 9\))

We’ll develop this properly in a later lecture, but here’s the key idea.

Imagine a star emitting light uniformly in all directions. That light spreads out over the surface of an expanding sphere. At distance \(d\), the sphere has surface area \(4\pi d^2\). The same total light is now spread over this larger area, so the flux (light per unit area) decreases:

\[ F = \frac{L}{4\pi d^2} \]

where:

- \(F\) = flux (what we measure, in erg s⁻¹ cm⁻²)

- \(L\) = luminosity (what the star emits, in erg s⁻¹)

- \(d\) = distance (in cm)

The key insight: Flux falls off as \(1/d^2\). Double the distance → quarter the brightness. This “inverse-square law” is why determining distances is so central to astronomy: if you know \(L\) (from a “standard candle”) and measure \(F\), you can solve for \(d\).

Why it matters: Almost every distance measurement beyond our solar system relies on some version of this relationship. The entire cosmic distance ladder is built on calibrating objects whose luminosity \(L\) we think we understand.

Rearranging for distance:

\[ d = \sqrt{\frac{L}{4\pi F}} \]

If you can determine \(L\) independently (from pulsation period, spectral type, or explosion physics), measuring \(F\) gives you \(d\).

Units check (CGS):

- \(L\) in erg/s

- \(d\) in cm

- \(4\pi\) is dimensionless

- \(F\) in erg s⁻¹ cm⁻² ✓

Physical intuition:

- The \(4\pi\) comes from the sphere’s geometry (full solid angle)

- The \(d^2\) comes from how area scales with radius

- This is purely geometric—it doesn’t depend on what kind of light or what kind of source

Connection to Spoiler 2: The cosmic distance ladder (Section 1.2) is built entirely on this relationship. Every “standard candle”—Cepheids, Type Ia supernovae—works because we can determine \(L\) independently and then solve for \(d\).

Throughout this course, equations serve two purposes:

- Orientation equations — Show the relationship (what depends on what). You won’t calculate with these yet; just notice the structure.

- Working equations — You’ll use these to solve problems. We’ll practice them explicitly.

For now, the inverse-square law (\(F = L/4\pi d^2\)) is a working equation—you’ll calculate with it soon. The wave relation (\(c = \lambda\nu\)) and photon energy (\(E = h\nu\)) are orientation equations for now; they become working tools once we develop atomic spectra.

We’ll return to the inverse-square law quantitatively when we build the distance ladder step by step.

Look at the first image in the spoiler reel below (the colorful nebulae). Before reading the explanation, jot down:

- What do you think the different colors might represent?

- What do you think the dark regions are?

There’s no wrong answer—this is about surfacing your intuitions. We’ll see how they compare to the physics.

1.2 The Spoiler Reel: A Tour of What’s Possible

What follows is a tour through some of the most spectacular astronomical images humanity has ever captured. But we’re not just sightseeing. For each image, we’ll ask three questions:

- What do we measure?

- What do we infer?

- What physics makes that inference legal?

The pattern to watch for: Every spoiler follows the same structure: measurement → model → inference. By the end of this course, you’ll be able to fill in the “what physics” part yourself.

You are not expected to understand all the answers yet. That’s what the rest of the semester is for. Today, we’re giving you the spoilers—showing you where we’re headed. By the end of the course, you’ll have earned the right to say these things with confidence.

The Narrative Arc: Where We’re Going

The images are organized to build your understanding progressively:

| # | Image | Key Question | What It Teaches |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Nebulae | What do colors mean? | Colors encode atomic physics |

| 2 | Distance Ladder | How far away are things? | Brightness enables distance measurement |

| 3 | Periodic Table | Where did the elements come from? | Stars are nuclear factories |

| 4 | Prism | How do we split light? | Spectroscopy is foundational |

| 5 | EM Spectrum | Why observe at different wavelengths? | Wavelength maps physical conditions |

| 6 | M51 (two views) | What does wavelength choice reveal? | Same object, different physics visible |

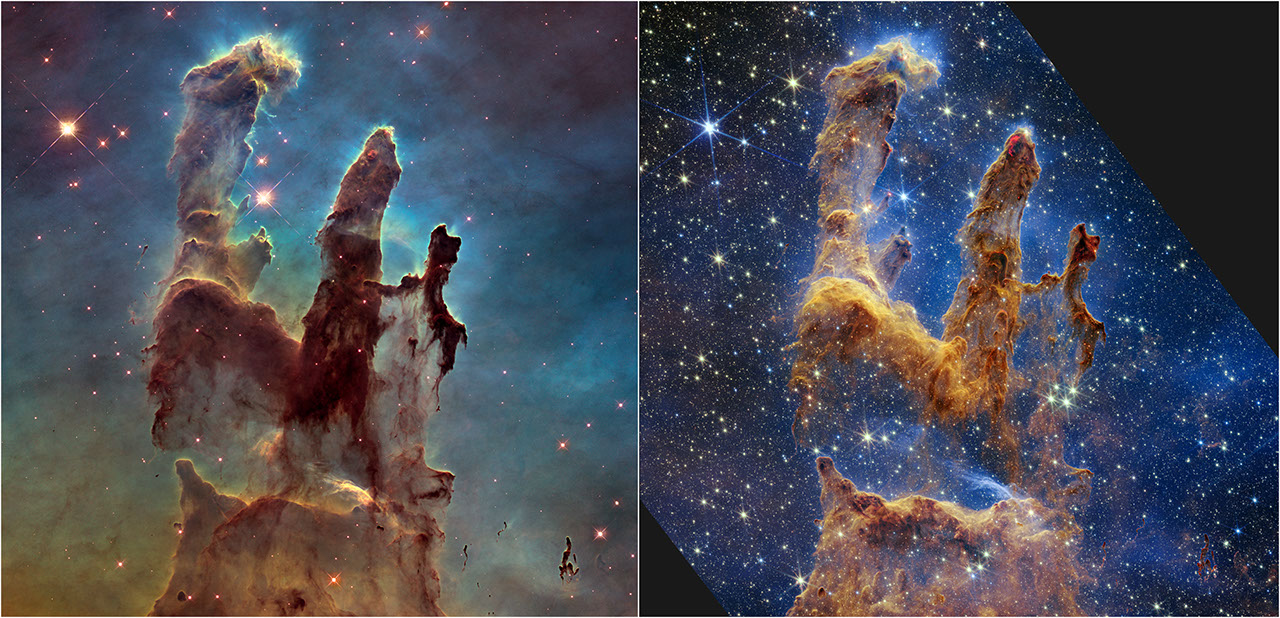

| 7 | Pillars of Creation | What can infrared see that visible can’t? | Infrared penetrates dust |

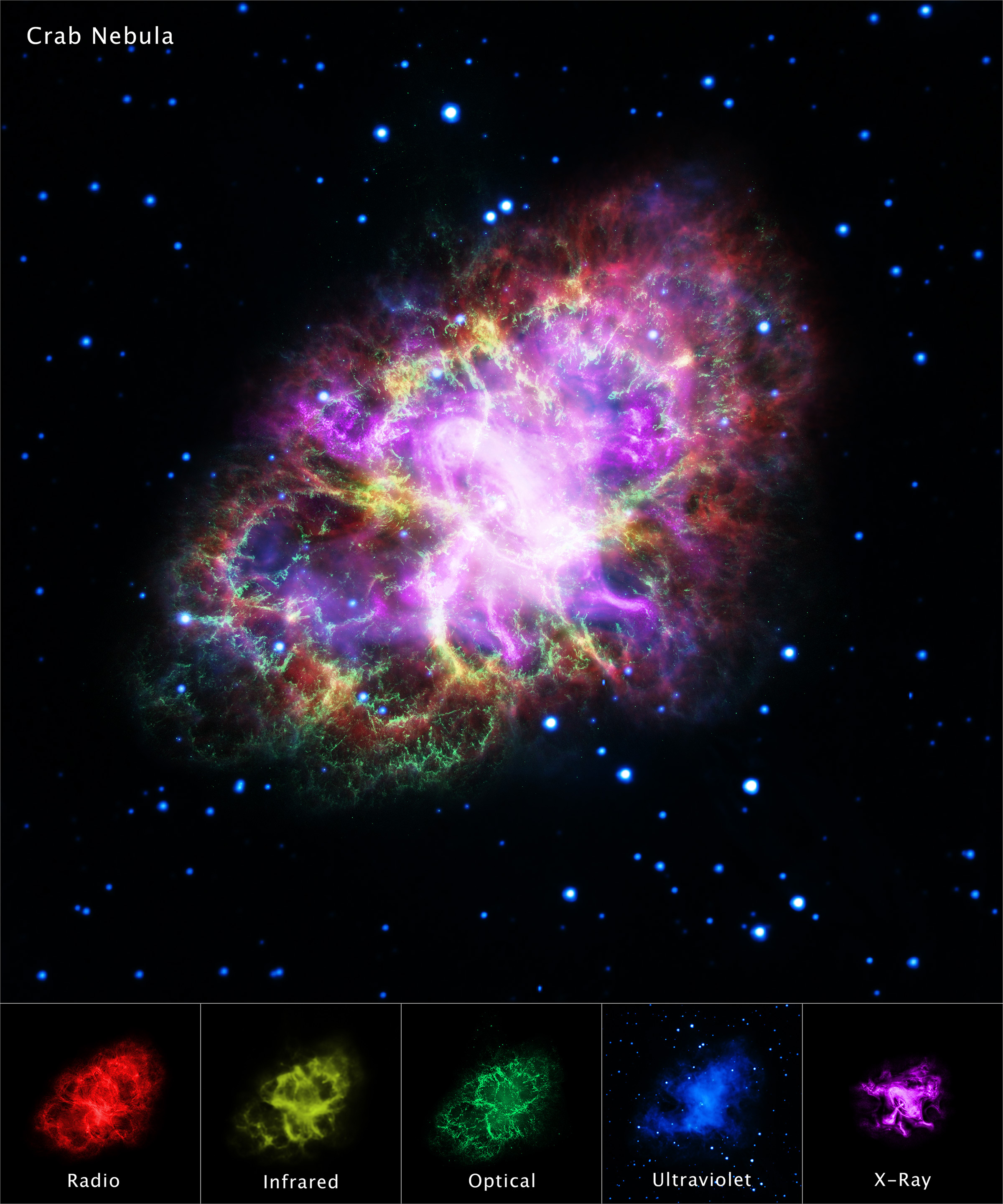

| 8 | Crab Nebula | How do we understand complex systems? | Combine wavelengths for complete picture |

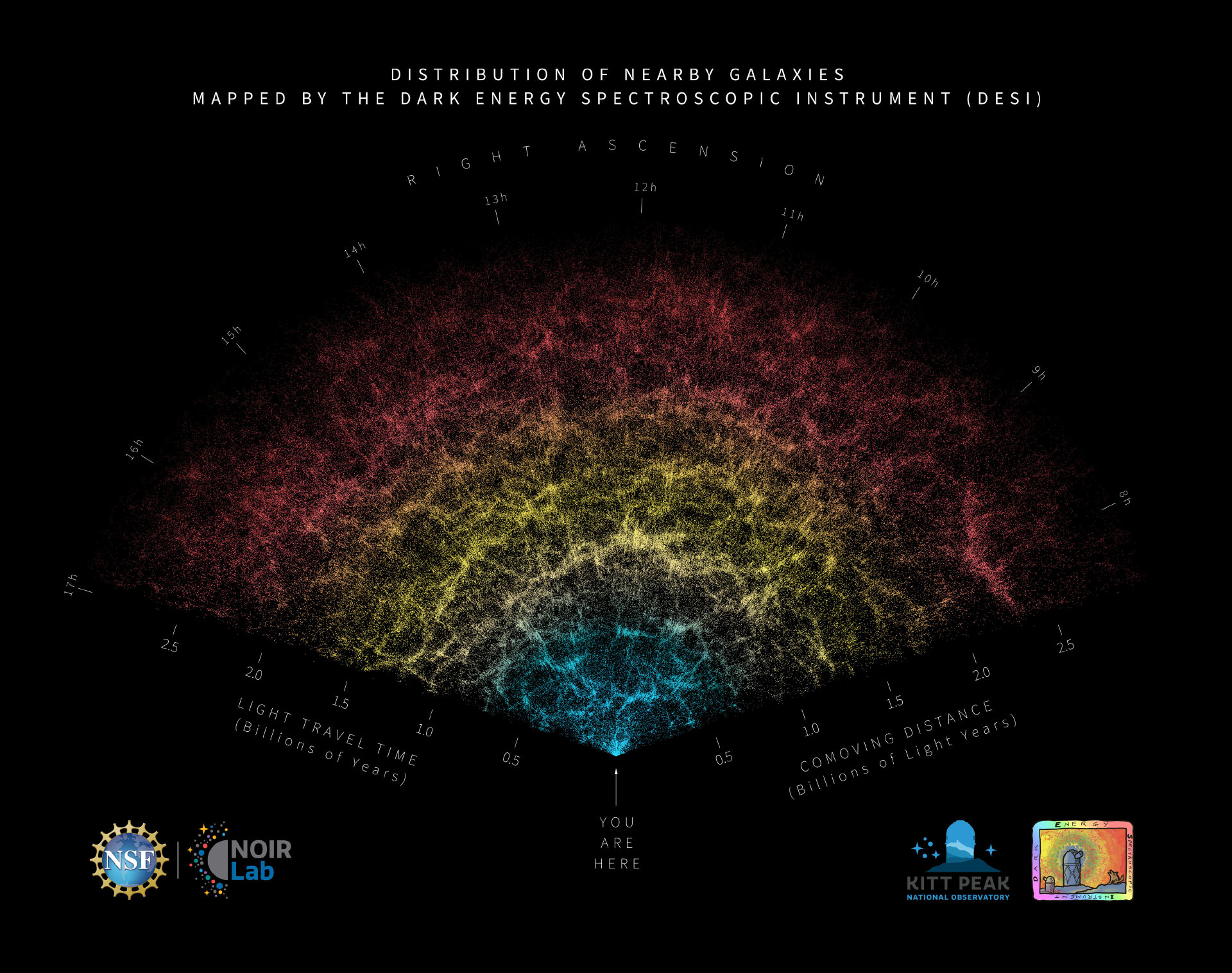

| 9 | LSST + DESI Map | What is most of the universe made of, and is it static? | Most matter is invisible; motion reveals mass; the cosmic web is still evolving |

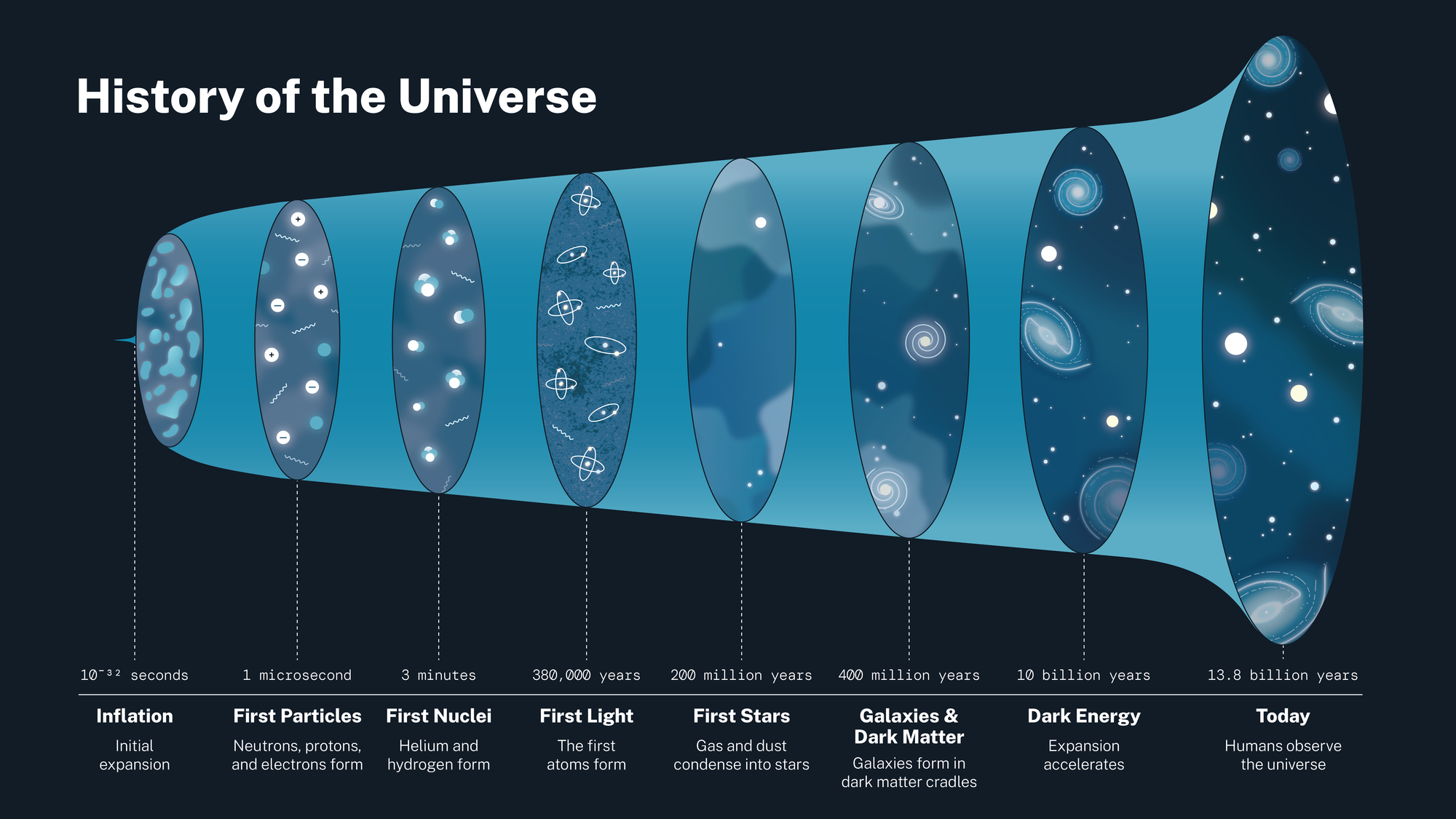

| 10 | History of the Universe | How old is the universe, and what is its fate? | Distance + expansion → age; acceleration reveals dark energy |

Each builds on the one before. Watch for the pattern, not the details.

Mini-Glossary (Orientation Only)

This glossary is here to help you recognize terms when you see them—not to memorize them. Every term below will be reintroduced later, in context, with time to understand it properly. For now, just scan and move on.

| Term | One-Line Definition |

|---|---|

| Photon | A “packet” of light; the quantum of electromagnetic radiation |

| Wavelength (λ) | The spatial period of a light wave; determines the “type” of light |

| Spectrum | Brightness measured as a function of wavelength |

| Flux | Light energy per unit time per unit area reaching your detector |

| Luminosity | Total light energy emitted by a source per unit time |

| Emission | Light produced and sent out by a source |

| Absorption | Light removed from a beam by intervening material |

| Extinction | Dimming of light by dust (absorption + scattering combined) |

| Ionized | An atom that has lost one or more electrons; electrically charged |

| Neutral | An atom with equal numbers of protons and electrons; no net charge |

| Thermal radiation | Light emitted due to an object’s temperature (all hot objects glow) |

| Dark matter | Invisible matter detected through gravity; outweighs visible matter ~5:1 |

| Dark energy | The unknown driver of accelerating cosmic expansion; ~68% of the universe |

| Redshift | Stretching of light wavelengths; for distant galaxies, caused by cosmic expansion |

If your brain feels full, that’s working as intended.

You’ve just scanned a glossary of unfamiliar terms, and ten spoilers are coming. Here’s what to remember:

- You are not expected to retain details. Recognition, not recall.

- Every term reappears later, with context and time to understand.

- The goal is pattern recognition: What do we measure? What do we infer? What physics makes it legal?

Take 60 seconds. Stretch. Then continue—watching for the pattern, not memorizing the parts.

Spoiler 1: Nebulae — Color as Encoded Physics

![Annotated nebula image showing three labeled features: (1) Hydrogen-Alpha at 656.3 nm in red regions indicating ionized gas, (2) Doubly-ionized Oxygen [OIII] at 500 nm in blue-green regions indicating extremely low density, (3) Dark Lanes showing silhouettes of interstellar dust blocking the light.](../../../assets/images/module-01/forensic-analysis-of-a-nebula-nblm.png)

What to notice: Colors aren’t decoration—they’re encoded physics. Red = hydrogen (656 nm), blue-green = oxygen (500 nm), dark lanes = dust blocking light. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

What do we measure? Structured colors at specific wavelengths. Red light at 656 nm. Blue-green light at 496–501 nm. Dark regions where light is blocked.

What do we infer? The red regions contain hydrogen gas that’s been heated and ionized by nearby hot stars. The blue-green regions contain oxygen. The dark lanes contain dust—tiny solid particles that absorb and scatter starlight.

What physics makes this legal? Atoms emit light at specific wavelengths, not random colors. Each element has a unique “fingerprint” of wavelengths determined by its atomic structure. When we see red light at exactly 656 nm, we know hydrogen is present.

Key insight: Color isn’t decoration—it’s encoded physics. Specific wavelengths = specific atoms = specific conditions.

The red glow comes from hydrogen’s “H-alpha” (Hα) transition at 656.3 nm. When an electron in a hydrogen atom drops from the n=3 to n=2 energy level, it releases a photon with exactly this wavelength. This isn’t arbitrary—it’s set by quantum mechanics. (We’ll explore atomic transitions when we develop the physics of spectra.)

The oxygen lines ([OIII] at 496–501 nm) come from “forbidden” transitions that only occur in extremely low-density gas—conditions impossible in Earth laboratories but common in space. The very presence of these lines tells us about gas density.

Key insight for now: Each element has a unique “fingerprint” of emission wavelengths. Detecting specific wavelengths tells you which atoms are present.

We’ll return to why these exact wavelengths appear once we’ve met spectra.

Transition: If colors encode what’s there, how do we figure out how far away it is?

Spoiler 2: The Distance Ladder — How Far Is Far?

What to notice: Each rung calibrates the next. Parallax (geometry) → Cepheids (standard candles) → Supernovae (Chandrasekhar limit) → Hubble Flow (cosmology). We infer the infinite from the infinitesimal. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

What do we measure? Apparent brightnesses of certain “milepost” objects—stars that pulsate in predictable ways, or stellar explosions that reach consistent peak brightness.

What do we infer? Distances far beyond what geometry alone can reach—out to billions of light-years.

What physics makes this legal? If you know how bright something truly is (its luminosity) and measure how bright it appears (its flux), the inverse-square law lets you calculate distance.

Standard candle: An object whose intrinsic luminosity can be determined independently (from pulsation period, spectral type, or explosion physics), allowing distance to be calculated from observed brightness.

Key insight: Distance is inferred from brightness. To measure farther, we need brighter standard candles.

The cosmic distance ladder works in steps:

- Radar (Solar System): Bounce radio waves off planets; measure round-trip time → distance directly

- Parallax (nearby stars): Measure apparent shift as Earth orbits Sun → geometry gives distance

- Cepheid variables (nearby galaxies): Pulsating stars whose period correlates with luminosity; measure period → infer luminosity → calculate distance

- Type Ia supernovae (distant universe): Thermonuclear explosions of white dwarfs with consistent peak luminosity → visible across billions of light-years

Each rung calibrates the next. Parallax calibrates Cepheids; Cepheids calibrate Type Ia supernovae. Uncertainty propagates upward—errors in lower rungs affect all higher rungs.

The ladder’s power comes from its self-consistency: multiple methods overlap in certain distance ranges, allowing cross-checks.

What to notice: Standard candles work because physics predicts their luminosity. Measure flux (F) + know luminosity (L) → calculate distance (d). (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

Transition: Distance tells us where things are. But what are they made of?

Spoiler 3: Origin of the Elements — Stars as Nuclear Factories

What to notice: The periodic table is a fossil record of cosmic processes. Different colors = different origins: Big Bang (H, He), dying stars (C, N, O), supernovae (Fe), neutron star mergers (Au, Pt). (Credit: NASA/Jennifer Johnson)

What do we measure? Element fingerprints in spectra—specific wavelengths absorbed or emitted—and abundances of elements in meteorites, stars, and gas clouds.

What do we infer? Different cosmic environments made different elements. The periodic table is a fossil record of astrophysical processes.

What physics makes this legal? Nuclear reactions require specific conditions (temperature, density) and have specific products. The elements we find are fossils of the processes that created them.

You are starstuff. The atoms in your body were manufactured in stellar cores and explosions, then scattered into space, then incorporated into a new solar system, then into you.

Key insight: Stars don’t just shine—they manufacture the periodic table.

- Big Bang nucleosynthesis (~3 minutes after the Big Bang): Produced H, He, trace Li

- Stellar core fusion (over millions–billions of years): H → He → C → O → … up to Fe

- Type Ia supernovae: Major producers of iron-peak elements—each explosion synthesizes ~0.6 \(M_\odot\) of ⁵⁶Ni (which decays to ⁵⁶Fe)

- Core-collapse supernovae: Produce elements up to Fe, plus some heavier via rapid neutron capture

- Neutron star mergers: Primary site for r-process elements (Au, Pt, U)—confirmed in 2017

Iron (Fe) is special: it’s the most tightly bound nucleus. Fusion to iron releases energy; fusion beyond iron requires energy input. This is why iron is the end of the line for stellar core burning—heavier elements require explosive environments.

Transition: We’ve mentioned “wavelengths” and “spectra” several times. What exactly is a spectrum?

Spoiler 4: Dispersion — The Key to Everything

What to notice: A prism reveals that ‘white’ light contains many wavelengths. Blue bends more (shorter λ, higher energy); red bends less (longer λ, lower energy). (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

What do we measure? When “white” light passes through a prism (or diffraction grating), it spreads into a rainbow.

What do we infer? Light contains many wavelengths simultaneously. “White” is a mixture; each color corresponds to a different wavelength.

What physics makes this legal? Different wavelengths travel at different speeds through glass, causing them to bend by different amounts and separate spatially.

Spectroscopy transformed astronomy from cataloging what’s there to understanding what it’s made of and how it works. It’s the difference between stamp collecting and physics.

The breakthrough: A prism doesn’t just make rainbows—it gives you the power to decode what’s hidden inside the light. This is spectroscopy, and it’s the most powerful tool in the astronomer’s toolkit.

Why is spectroscopy more powerful than just measuring total brightness?

(Think first… then check: Spectroscopy spreads light into its component wavelengths, giving you brightness as a function of wavelength—thousands of data points instead of one. This reveals temperature, composition, and motion that a single brightness measurement cannot.)

What to notice: Atoms have quantized energy levels like rungs on a ladder. Electrons jumping between rungs absorb or emit photons of exact energies—creating unique spectral fingerprints. Hot dense sources produce continuous spectra; cool gas in front absorbs specific wavelengths; hot thin gas emits specific wavelengths. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

But why do atoms produce light at specific wavelengths rather than a continuous rainbow? The answer is quantum mechanics: electrons in atoms can only occupy certain discrete energy levels. When an electron jumps between levels, it absorbs or emits a photon of exactly the right energy—and energy determines wavelength. Each element’s unique ladder of energy levels creates its unique spectral fingerprint.

Here’s something crucial: those fingerprints are stable—hydrogen always produces the same pattern of wavelengths. But when the source moves toward or away from us, the entire fingerprint shifts in wavelength. Moving toward us? The wavelengths compress (shift blue). Moving away? They stretch (shift red). This is the Doppler effect, and it’s how we measure the speeds of stars, galaxies, and the expanding universe itself—using light alone.

If spectroscopy reveals what something is made of, the Doppler shift reveals how it’s moving. Together, they let us turn distant points of light into physical systems we can understand.

The Doppler effect may seem abstract now. That’s fine—we’re just tagging it as important. When we return to it later, you’ll see it power some of the most dramatic inferences in astronomy: measuring dark matter, mapping the expanding universe, detecting planets around other stars.

For now: recognize the name, not the details.

Transition: The rainbow from a prism shows visible light. But visible light is just a tiny slice of all the light that exists…

Spoiler 5: The Electromagnetic Spectrum — A Map of Physical Processes

What to notice: The EM spectrum is a temperature ladder. Gamma/X-ray = million-degree plasma; UV/Visible = stellar surfaces (3,000–50,000 K); Infrared/Radio = dust and cold gas (10–100 K). (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

What do we measure? Photons across the entire electromagnetic spectrum—from radio waves with wavelengths of meters to gamma rays smaller than atoms.

What do we infer? Different physical conditions produce different wavelengths. Cold gas glows at radio wavelengths; stellar surfaces shine in visible light; million-degree plasma emits X-rays.

What physics makes this legal? Photon energy is tied to wavelength. Hotter or more violent processes produce higher-energy (shorter-wavelength) photons.

The hierarchy:

- Longer λ → lower energy → colder/gentler

- Shorter λ → higher energy → hotter/more violent

Bottom line: Wavelength tells you about temperature and violence. The EM spectrum is organized by physics, not human convention—it’s a map of physical conditions.

Feeling overwhelmed? That’s the point.

You’re not supposed to understand all of this yet. What I want you to notice is the pattern: measure → infer → physics makes it legal. That pattern is the same every time.

The next three spoilers show how wavelength choice reveals different physics in the same objects. Keep watching for the pattern.

Spoiler 6: Same Galaxy, Different Physics

What to notice: Left (optical) shows stars and dust lanes. Right (radio/21-cm) shows cold neutral hydrogen gas. The distributions don’t perfectly overlap—different wavelengths reveal different physical components. (Credit: NASA/ESA/STScI/AURA (Optical); NRAO/AUI (Radio))

What do we measure? Optical starlight (~500 nm) from one observation; radio emission at 21 cm from another.

What do we infer? The optical image shows where the stars are. The radio image shows where cold hydrogen gas lives. They don’t perfectly overlap.

What physics makes this legal? Stars emit thermal radiation from their hot surfaces (peaks in visible). Neutral hydrogen emits at exactly 21 cm due to a quantum mechanical transition in cold atomic gas.

Key insight: Same object + different wavelength = different physical component revealed.

The 21-cm line arises from the hyperfine structure of hydrogen. The electron and proton can have parallel or anti-parallel spins. When an electron “flips” from parallel to anti-parallel, it emits a photon with wavelength 21.1 cm (frequency 1420 MHz).

This transition is “forbidden”—extremely unlikely on short timescales—but there’s so much hydrogen in the universe that we detect it easily. The 21-cm line traces neutral atomic hydrogen specifically; ionized hydrogen doesn’t emit it.

Doppler connection: The 21-cm line has a precise rest wavelength. When hydrogen gas is moving toward or away from us, the line shifts—and the amount of shift tells us how fast the gas is moving. This is how astronomers measure galaxy rotation curves: hydrogen on one side of a spinning galaxy is blueshifted (approaching); hydrogen on the other side is redshifted (receding). The Doppler effect turns a single spectral line into a velocity map.

Transition: Optical shows stars, but what if dust is blocking our view of where stars are born?

Spoiler 7: Pillars of Creation — Infrared Beats Dust

What to notice: Left (Hubble optical)—dark, opaque columns block visible light. Right (JWST infrared)—thousands of embedded newborn stars revealed. Infrared penetrates the dust that blocks optical light. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

What do we measure? Optical: dark pillars. Infrared: thousands of previously hidden stars.

What do we infer? Dust strongly blocks visible light but is transparent at infrared wavelengths. The “empty” dark regions are teeming with newborn stars.

What physics makes this legal? Dust grains (~0.01–1 μm) efficiently absorb and scatter light with comparable wavelengths. Longer wavelengths (infrared) pass through.

JWST’s superpower: At ~2 μm wavelength, dust absorbs roughly 10× less light than at visible wavelengths. JWST peers through cosmic dust that blocks Hubble.

Key insight: What you can’t see at one wavelength might be brilliantly visible at another.

Transition: We’ve seen how one alternative wavelength reveals hidden physics. What about combining many wavelengths?

Spoiler 8: The Crab Nebula — Many Windows, One Truth

What to notice: The same supernova remnant looks completely different at each wavelength. Radio (red) = synchrotron from magnetic fields; Infrared (yellow) = warm dust; Optical (green) = ionized filaments; X-ray (blue/purple) = hot plasma and pulsar jets. Many windows, one truth. (Credit: NASA/CXC/SAO)

What do we measure? The Crab observed from radio through X-ray. At each wavelength, it looks completely different.

What do we infer? Multiple physical components coexist: - Radio: Magnetic fields + relativistic electrons - Infrared: Warm dust - Optical: Ionized gas from the 1054 CE supernova - X-ray: Hot plasma and the central pulsar’s jets

What physics makes this legal? Different emission mechanisms dominate at different wavelengths.

Key insight: Many windows, one truth. Only by combining wavelengths can we understand complex astrophysical systems.

Spoiler 9: The Dark Universe — Most of Reality Is Invisible (and Not Static)

What to notice: A single deep-field image contains thousands of galaxies at different distances—each a snapshot from a different cosmic era. This is Rubin Observatory’s first light ‘Cosmic Treasure Chest’. (Credit: Rubin Observatory/NSF/AURA)

What do we measure? Velocities—and here’s how. When we spread starlight into a spectrum, we see absorption lines at specific wavelengths (the fingerprints from Spoiler 4). If those lines appear shifted from their laboratory (at-rest) wavelengths, the source is moving: lines shift → velocity. This is the Doppler effect in action. We measure how fast stars orbit within galaxies and how fast galaxies move within clusters—all by detecting tiny wavelength shifts in their spectra. We also measure how light bends as it passes near massive objects (gravitational lensing).

Why velocities matter: Here’s the critical inference chain. Objects in orbit are constantly accelerating (changing direction). Acceleration requires a force. In space, the only force acting at these scales is gravity. And gravitational force depends on mass. So: Doppler shift → velocity → acceleration → gravitational force → mass. The Doppler effect is what makes this chain possible—it converts light into velocities.

What do we infer? Galaxies rotate too fast. Stars in the outer regions orbit at speeds that should fling them into intergalactic space—unless there’s far more mass than we can see. The same is true for galaxy clusters: galaxies move too fast to be held together by visible matter alone. When we calculate the mass required to explain the observed motions, it exceeds the visible mass by a factor of ~6. We infer the presence of dark matter—matter that doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light, but does exert gravitational pull.

What physics makes this legal? Newton’s law of gravity tells us that orbital speed depends on enclosed mass: \(v^2 = GM/r\). Measure \(v\) and \(r\), solve for \(M\). The math is unambiguous. The extra mass is real—we detect it through the motions it causes.

What to notice: The cosmic web—galaxies aren’t scattered randomly. They cluster into filaments, walls, and voids. You are at the center; colors show distance (cyan = nearby, red = billions of light-years away). Gravity is still pulling these structures together. (Credit: DESI Collaboration/NOIRLab/NSF/AURA/Kitt Peak)

The cosmic web: When we map millions of galaxies in 3D (using redshifts for distances), we see that galaxies aren’t scattered randomly—they’re organized into a cosmic web of filaments, walls, and vast empty voids. This architecture is dark matter’s signature at the largest scales. And it’s still evolving: gravity pulls matter from voids into filaments, from filaments into clusters. The largest structures in the universe are still collapsing.

We don’t know what most of the universe is made of—and it’s not sitting still.

The cosmic recipe:

- ~5% ordinary matter — atoms, stars, planets, you

- ~27% dark matter — invisible mass that holds galaxies together

- ~68% dark energy — the mysterious driver of accelerating expansion

Only 5% of the universe is made of the stuff we understand. The rest is dark—but not undetectable. We see dark matter through the motions it causes: stars orbiting too fast, galaxies moving too quickly, the cosmic web still tightening under gravity’s pull.

The evidence for dark matter:

Galaxy rotation curves: Stars at large radii orbit at roughly constant speed, not the declining speed expected if mass were concentrated in the visible center. This “flat rotation curve” implies mass extending far beyond the visible disk.

Galaxy cluster dynamics: Fritz Zwicky noticed in the 1930s that galaxies in the Coma Cluster move too fast—the cluster should have flown apart long ago unless there’s ~10× more mass than visible.

Gravitational lensing: Massive objects bend light. The amount of bending reveals the total mass, including dark matter. Lensing maps consistently show dark matter halos extending well beyond visible galaxies.

Cosmic microwave background: The pattern of temperature fluctuations in the CMB encodes information about the matter content of the early universe. The pattern requires dark matter to match observations.

Large-scale structure: The cosmic web we see today—filaments, walls, voids—could only form if dark matter provided the gravitational scaffolding. Simulations without dark matter produce nothing like the observed universe.

What dark matter is NOT:

- It’s not failed stars, rogue planets, or black holes (we’ve looked)

- It’s not ordinary matter hiding in some unseen form

- It’s not a modification of gravity (though some physicists explore this)

What it might be: A new type of particle that interacts via gravity but not electromagnetism. Candidates include WIMPs (Weakly Interacting Massive Particles), axions, and others. Despite decades of searching, we haven’t detected dark matter particles directly—yet.

Connection to Course: Later, we’ll derive galaxy rotation curves and see how dark matter changes everything we thought we knew about cosmic structure.

Key insight: Motion reveals mass. Gravity causes acceleration; we measure velocities; the math tells us how much mass is required. Most of it is invisible—but the universe is not static, and gravity is still the architect, still building today.

Transition: Dark matter tells us that most matter is invisible. But there’s something even stranger: most of the universe’s energy content isn’t matter at all…

Spoiler 10: Cosmic History — 13.8 Billion Years and Accelerating

What to notice: The universe has a history. Inflation (10⁻³² s) → First Particles (1 μs) → First Nuclei (3 min) → First Light (380,000 yr) → First Stars (200 Myr) → Galaxies (400 Myr) → Dark Energy (10 Gyr) → Today (13.8 Gyr). (Credit: NASA)

What do we measure? Two things: distances to objects across cosmic history (using the distance ladder from Spoiler 2) and their recession speeds. How do we get recession speeds? Through redshift—the Doppler shift we introduced in Spoiler 4. When we spread a galaxy’s light into a spectrum, its spectral lines appear shifted toward longer (redder) wavelengths compared to laboratory (at-rest) values. The amount of shift tells us how fast the galaxy is moving away. By combining distances with redshifts for objects at different epochs, we reconstruct how the universe has expanded over time.

What do we infer?

- The universe is 13.8 billion years old—traced back from the observed expansion rate.

- The expansion was initially slowing down (gravity pulling matter together), but about 5 billion years ago, it started speeding up.

- Something is pushing the universe apart faster and faster. We call it dark energy.

What physics makes this legal?

If you know how fast galaxies are receding and how far away they are, you can “run the movie backward” to find when everything was in the same place—the Big Bang. Careful measurements give 13.8 billion years.

The acceleration was discovered in 1998 by measuring Type Ia supernovae at large distances. These “standard candles” appeared fainter than expected—meaning they were farther away than a decelerating universe would predict. The universe’s expansion is speeding up, not slowing down.

This was not predicted—in fact, it contradicted the prevailing expectation that gravity should be decelerating expansion. The universe broke the model, and cosmology had to revise. That’s how science works: when observations surprise us, we update.

The universe is 13.8 billion years old, it’s expanding, and that expansion is accelerating.

- Age: Inferred from expansion history traced back to a common origin

- Expansion: Every distant galaxy is moving away from us; the farther, the faster

- Acceleration: Discovered in 1998; earned the 2011 Nobel Prize in Physics

- Cause: Unknown. We call it “dark energy,” but that’s a name for our ignorance.

Key epochs in cosmic history:

| Time | Event | What Happened |

|---|---|---|

| 10⁻³² s | Inflation | Exponential expansion; sets initial conditions |

| 10⁻⁶ s | Quark confinement | Quarks bind into protons and neutrons |

| 3 min | Nucleosynthesis | H, He, trace Li formed; ~75% H, 25% He by mass |

| 380,000 yr | Recombination | Atoms form; universe becomes transparent; CMB released |

| 200 Myr | First stars | Population III stars ignite; cosmic “dawn” |

| 400 Myr | First galaxies | Dark matter halos host early galaxy formation |

| ~10 Gyr | Dark energy dominance | Expansion begins accelerating |

| 13.8 Gyr | Today | You’re reading this |

How we know the age:

The expansion rate today is called the Hubble constant (\(H_0 \approx 70\) km/s/Mpc). Naively, \(1/H_0\) gives a rough age estimate (~14 Gyr). Precise age requires accounting for how expansion rate changed over time—which depends on the matter/energy content. Current best value: \(13.8 \pm 0.02\) billion years.

The accelerating expansion:

In 1998, two teams (Supernova Cosmology Project and High-Z Supernova Search) measured Type Ia supernovae at redshifts \(z \sim 0.5\)–\(1\). These standard candles appeared ~25% fainter than expected in a decelerating universe. The only explanation: the expansion rate has been increasing for the past ~5 billion years.

What is dark energy?

We don’t know. Options include:

- Cosmological constant (Λ): A constant energy density built into spacetime itself

- Quintessence: A dynamic field that changes over time

- Modified gravity: Perhaps general relativity needs revision on cosmic scales

The simplest model (ΛCDM) treats dark energy as a cosmological constant. It fits observations remarkably well—but we have no physical understanding of why it has the value it does.

Connection to Course: We’ll develop the Hubble law, explore evidence for dark energy, and discuss the fate of the universe (spoiler: it keeps expanding forever, growing colder and emptier).

Key insight: We can measure the age and fate of the universe—using the same tools we used to measure the distance to a nearby star. The method scales.

Today’s images were conclusions—answers to questions we haven’t formally asked yet. The rest of this semester is about earning the right to say them.

The pattern:

- We measure limited things: brightness, position, wavelength, timing

- We apply physical models connecting observables to properties

- We infer quantities we can’t directly access

- We make predictions and test them

What the spoilers revealed:

- Colors encode atoms (nebulae)

- Brightness enables distance (ladder)

- Spectra reveal origin (elements)

- Spectroscopy is foundational (prism)

- EM spectrum maps conditions (temperature ladder)

- Wavelength choice reveals components (M51, Pillars, Crab)

- Most matter is invisible and the universe is not static—dark matter shapes the still-evolving cosmic web

- The universe is 13.8 Gyr old, expanding, and accelerating

That framework—measurement → model → inference → test—is the decoder ring.

If this reading felt overwhelming in places, that’s not a warning sign—it’s evidence that your brain has been introduced to a new landscape. You are not expected to carry these details yet. You are expected to recognize them when we meet them again, with tools in hand.

1.3 The Decoder Ring: Physics as the Rosetta Stone

Model: A mathematical relationship encoding physical assumptions. Models connect what we measure to what we want to know—and they can be tested.

The spoiler reel showed you what’s possible. Now let’s make the method explicit.

Astronomy works because we follow a systematic process:

Signal → Measurement → Model → Inference → Prediction → Test

What to notice: The cycle that makes astronomy a science: Signal → Measurement → Model → Inference → Correction → back to Model. Failed predictions drive model revision. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

- Signal: The universe sends us electromagnetic radiation—photons.

- Measurement: We detect and quantify those signals.

- Model: We apply physical relationships that connect observables to physical quantities.

- Inference: Model + measurement yields something we couldn’t directly measure.

- Prediction: The model tells us what else should be true.

- Test: We compare predictions to new observations.

When tests fail, we revise models. That cycle is how science progresses.

What to notice: The tools we’ll learn answer humanity’s biggest questions: distance measurements give the universe’s age, spectroscopy proves our stellar origins, atmospheric analysis searches for life. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

Physics tells you what relationships are allowed.

You can’t invent a connection between brightness and temperature. Physical laws emerge from how the universe actually works.

Math makes assumptions explicit and checkable.

An equation forces precision: What’s constant? What’s assumed? What are the units? Math lets you trace logic and identify where errors enter.

The Physical Quantities We Care About

Here’s the distinction that makes astronomy both hard and fascinating:

- The Four Observables (Section 1.1): What we can directly measure—brightness, position, wavelength, timing.

- The Six Core Quantities (below): What we actually want to know about stars and galaxies.

Notice that none of the quantities below appear in the observables list. Every single one must be inferred by combining measurements with physical models. That gap—between what we measure and what we want to know—is where physics lives.

| Quantity | Symbol | What it measures | How We Infer It | CGS Units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Distance | \(d\) | How far away | Parallax (position), standard candles (brightness) | cm (or pc, ly) |

| Time | \(t\) | Duration or epoch | (context-dependent) | s (or yr) |

| Speed | \(v\) | Rate of motion | Doppler shift (wavelength) | cm/s |

| Mass | \(M\) | Amount of matter | Orbital motion (position + timing) | g (or \(M_\odot\)) |

| Energy / Luminosity | \(E\), \(L\) | Total energy; energy output per time | Flux (brightness) + distance | erg; erg/s (or \(L_\odot\)) |

| Temperature | \(T\) | Thermal energy scale | Spectrum/color (wavelength) | K |

Solar units (\(M_\odot\), \(L_\odot\), \(R_\odot\)) are often more intuitive than CGS for stellar astronomy. “This star is 10 \(M_\odot\)” means “10 times the Sun’s mass.”

Every value in the “How We Infer It” column connects back to one or more of the four observables via a physical model. That’s the course thesis in table form.

These quantities are connected by physical laws. Mass determines gravity. Temperature determines spectrum. Distance relates flux to luminosity. You’ll build the network of relationships throughout the semester.

Energy vs. Luminosity: You know energy from physics—the capacity to do work, measured in erg or Joules. In astronomy, we often use luminosity: energy emitted per unit time (power), measured in erg/s or \(L_\odot\). A star’s luminosity tells you how fast it’s radiating energy. The two are related: total energy output = luminosity × time.

1.4 Light: The Cosmic Messenger

Everything we know about the universe beyond Earth comes from light—electromagnetic radiation traveling across the cosmos carrying information. Understanding light is foundational.

The Speed of Light: A Universal Constant

Why “c”? From celeritas, Latin for “swiftness.” It’s one of the most fundamental constants in physics—the speed limit of the universe.

Light travels at a constant speed in vacuum:

\[ c = 2.998 \times 10^{10} \text{ cm/s} \approx 3 \times 10^{10} \text{ cm/s} \]

This is fast—about 300,000 km/s, fast enough to circle Earth 7.5 times in one second. But it’s also finite, and that finiteness has profound consequences.

To build intuition: - Light crosses your room almost instantaneously - Light from the Sun takes 8.3 minutes to reach Earth - Light from the nearest star takes 4.2 years - Light from the Andromeda Galaxy takes 2.5 million years

The light-year—the distance light travels in one year—is roughly \(10^{18}\) cm, or about 63,000 AU.

Light as a Wave: The Fundamental Relationship

Light is an electromagnetic wave—oscillating electric and magnetic fields propagating through space. Like any wave, it has a wavelength (\(\lambda\)): the distance between successive crests.

The relationship between wavelength, frequency, and speed is:

\[ c = \lambda \nu \tag{1}\]

where:

- \(c\) = speed of light (\(3 \times 10^{10}\) cm/s) — constant

- \(\lambda\) = wavelength (cm)

- \(\nu\) = frequency (Hz = cycles per second)

Wave relation (speed, wavelength, frequency)

What it predicts

Given any two of \(c\), \(\lambda\), \(\nu\), it predicts the third.

What it depends on

\(\lambda \propto \nu^{-1}\) (inverse relationship at fixed \(c\)).

What it's saying

Wavelength and frequency are two ways of describing the same wave; longer wavelength means lower frequency.

Assumptions

- Light travels in vacuum at speed \(c\)

- Applies to all electromagnetic radiation

See: the equation

Hertz (Hz): Unit of frequency; 1 Hz = 1 cycle per second. Named after Heinrich Hertz, who first demonstrated electromagnetic waves.

Units check: \([\lambda][\nu] = \text{cm} \times \text{s}^{-1} = \text{cm/s} = [c]\) ✓

Since \(c\) is constant, wavelength and frequency are inversely related: longer wavelength means lower frequency, and vice versa.

Doppler preview: If a light source moves toward you, the wavelengths you receive are compressed (shifted blue). If it moves away, wavelengths are stretched (shifted red). The speed of light stays constant—what changes is the wavelength. We’ll see this Doppler effect power major discoveries: dark matter, the expanding universe, and exoplanets.

Red light has wavelength \(\lambda \approx 700\) nm \(= 7 \times 10^{-5}\) cm. What’s its frequency?

Calculate: \[ \nu = \frac{c}{\lambda} = \frac{3 \times 10^{10} \text{ cm/s}}{7 \times 10^{-5} \text{ cm}} \approx 4.3 \times 10^{14} \text{ Hz} \]

That’s 430 trillion oscillations per second!

Unit check: \(\dfrac{\text{cm/s}}{\text{cm}} = \dfrac{1}{\text{s}} = \text{Hz}\) ✓

Limiting case: Blue light (\(\lambda \approx 400\) nm) has shorter wavelength. Since \(\nu = c/\lambda\), shorter λ means higher ν. Without calculating: blue should have roughly \((700/400) \approx 1.7×\) higher frequency. Check: \(\nu_\text{blue} \approx 7.5 \times 10^{14}\) Hz, which is indeed ~1.7× larger. ✓

Pattern: Shorter wavelength → higher frequency. This inverse relationship will appear throughout the course.

Radio waves have wavelengths of ~1 meter. Visible light has wavelengths of ~500 nm (\(5 \times 10^{-5}\) cm). Which has higher frequency, and by roughly how much?

(Think first… then check: Visible light has much higher frequency. Since \(\nu = c/\lambda\), shorter wavelength means higher frequency. Visible light’s wavelength is about \(10^7\) times smaller than radio, so its frequency is about \(10^7\) times higher.)

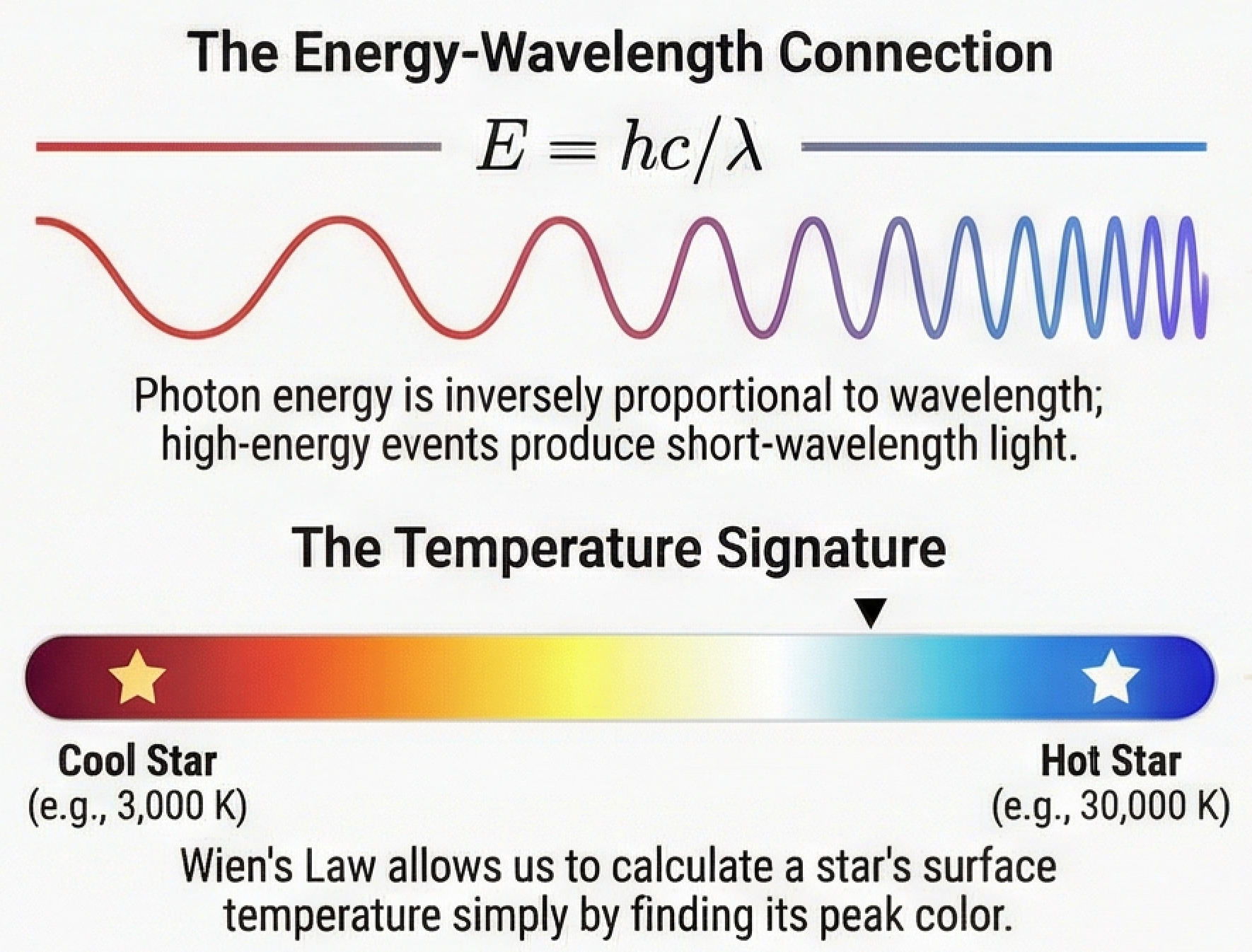

Photon Energy: Where Quantum Mechanics Enters

Photon

Light isn’t just a wave—it also comes in discrete packets called photons. Each photon carries a specific amount of energy:

\[ E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1} \tag{2}\]

where \(h = 6.63 \times 10^{-27}\) erg·s is Planck’s constant.

Photon energy (Planck relation)

What it predicts

Given wavelength \(\lambda\) (or frequency \(\nu\)), it predicts the energy \(E\) of a single photon.

What it depends on

\(E \propto \nu\) and \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\).

What it's saying

Shorter wavelength = higher energy photon. The constant \(h\) signals quantum mechanics is at work.

Assumptions

- Light comes in discrete packets (photons)

- Each photon carries energy proportional to its frequency

- This is a quantum mechanical result—classical physics cannot predict it

See: the equation

The constant \(h\) signals quantum territory. Atoms behave by different rules than everyday objects. We’ll explore why when we study atomic spectra; for now, the key result is that photon energy depends on wavelength.

The constant \(h\) (Planck’s constant) signals we’re in quantum territory—atoms and light behave by different rules than everyday objects.

Classical physics treated light as a continuous wave, but experiments showed that light comes in discrete energy packets called photons. The energy of each photon is set by its frequency (or equivalently, its wavelength).

We’ll unpack why this happens when we study atomic spectra and blackbody radiation. For now, the key message is: photon energy depends on wavelength, and shorter wavelength means higher energy.

Shorter wavelength = higher photon energy.

- Halve the wavelength → double the energy

- Radio photons (λ ~ meters) carry tiny energies (~\(10^{-19}\) erg)

- Gamma-ray photons (λ ~ \(10^{-12}\) cm) carry enormous energies (~\(10^{-6}\) erg)

This is why different wavelengths reveal different physics: it takes hot, energetic processes to produce high-energy photons.

We’ll return to photon energy when we explore why atoms emit light at specific wavelengths—and how this reveals stellar composition.

How much more energy does an X-ray photon carry compared to a radio photon?

Given:

- X-ray: \(\lambda_\text{X} = 1\) nm \(= 10^{-7}\) cm

- Radio: \(\lambda_\text{R} = 1\) m \(= 10^2\) cm

Calculate the ratio:

Since \(E = hc/\lambda\), the ratio of energies is: \[ \frac{E_\text{X-ray}}{E_\text{radio}} = \frac{hc/\lambda_\text{X}}{hc/\lambda_\text{R}} = \frac{\lambda_\text{R}}{\lambda_\text{X}} = \frac{10^2 \text{ cm}}{10^{-7} \text{ cm}} = 10^9 \]

Unit check: The \(hc\) cancels, and cm/cm is dimensionless. ✓

Limiting case: What if we used gamma rays instead (\(\lambda \sim 10^{-10}\) cm)? The ratio becomes \(10^2/10^{-10} = 10^{12}\)—a trillion times more energy than radio. The pattern holds: shorter λ → higher E.

Interpretation: X-ray photons carry a billion times more energy than radio photons. This explains why X-ray emission requires million-degree plasma, while radio emission can come from cold gas. Energy determines what processes can produce the light.

The Electromagnetic Spectrum: A Temperature Ladder

Combining \(c = \lambda\nu\) and \(E = h\nu\), we understand the EM spectrum as a map of physical conditions:

| Wavelength Range | λ (approximate) | Photon Energy | Typical Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radio | cm – m | ~\(10^{-19}\) erg | Cold gas, magnetic fields |

| Infrared | 1 μm – 1 mm | ~\(10^{-14}\) erg | Warm dust, cool stars |

| Visible | 400 – 700 nm | ~\(10^{-12}\) erg | Stellar surfaces |

| Ultraviolet | 10 – 400 nm | ~\(10^{-11}\) erg | Hot stars |

| X-ray | 0.01 – 10 nm | ~\(10^{-9}\) erg | Hot plasma (\(10^6\) K) |

| Gamma-ray | < 0.01 nm | > \(10^{-8}\) erg | Extreme events |

Temperature ladder: Cold things glow at long wavelengths; hot things at short wavelengths. Physics, not convention.

This hierarchy emerges from physics: hotter objects emit higher-energy (shorter-wavelength) photons. Different wavelengths probe different temperature regimes.

What to notice: E = hc/λ means shorter wavelength = higher energy. Wien’s Law lets us calculate temperature from color: cool stars are red (~3,000 K), hot stars are blue (~30,000 K).

The relationship between temperature and peak emission wavelength is quantified by Wien’s displacement law:

\[ \lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1} \tag{3}\]

where \(b = 0.29\) cm·K is Wien’s displacement constant.

Wien's displacement law

What it predicts

Given temperature \(T\), it predicts the peak wavelength \(\lambda_{\text{peak}}\) of thermal emission.

What it depends on

\(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\).

What it's saying

Hotter objects peak at shorter wavelengths (bluer); cooler objects peak at longer wavelengths (redder).

Assumptions

- Object radiates as a blackbody (or approximately so)

- Applies to thermal (temperature-driven) radiation

See: the equation

Examples:

- Sun (\(T \approx 5800\) K): \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \approx 500\) nm (visible)

- Human body (\(T \approx 300\) K): \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \approx 10\) μm (infrared)

- Cosmic microwave background (\(T = 2.7\) K): \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \approx 1\) mm

This is why thermal cameras “see” people in the dark (we glow in IR) and why the early universe is visible in microwaves.

Why do X-ray telescopes see different objects than optical telescopes?

(Think first… then check: X-ray photons have much higher energy than optical photons, requiring much hotter sources. X-ray telescopes detect million-degree plasma—gas in galaxy clusters, matter falling into black holes, stellar coronae—while optical telescopes see stellar surfaces at thousands of degrees. Different wavelengths = different temperature regimes = different objects visible.)

1.5 Looking Back in Time: The Universe as Time Machine

Lookback time: The time light takes to travel from an object to us. Because that’s also when the light was emitted, we see distant objects as they were in the past.

Light’s finite speed has a profound consequence for astronomy that deserves its own section.

When you look at the Sun, you see it as it was 8.3 minutes ago. The “Sun right now” is inaccessible—you can only see the “Sun 8.3 minutes ago.”

For the Sun, this seems like a curiosity. For distant objects, it becomes transformative:

What to notice: Distance is a time dial. Looking at the Moon = 1.3 seconds ago; the Sun = 8 minutes ago; Andromeda = 2.5 million years ago; distant galaxies = 10 billion years ago. (Credit: Course illustration (A. Rosen))

| Object | Distance | You See It As It Was… |

|---|---|---|

| The Moon | 1.3 light-seconds | 1.3 seconds ago |

| The Sun | 8.3 light-minutes | 8.3 minutes ago |

| Jupiter (opposition) | ~35 light-minutes | ~35 minutes ago |

| Proxima Centauri | 4.2 light-years | 4.2 years ago |

| Galactic center | ~26,000 light-years | When humans were painting caves |

| Andromeda Galaxy | 2.5 million light-years | Before Homo sapiens existed |

| Distant quasars | 10–13 billion light-years | When the universe was young |

Distance is a time dial. The farther we look, the further back we see.

This isn’t a limitation—it’s a feature. We can directly observe cosmic history by looking at objects at different distances.

Cosmic horizons: Each distance shell is a different epoch in cosmic history.

When we observe a galaxy 10 billion light-years away, we see it as it was 10 billion years ago—when the universe was young, when stars formed differently, when galaxies were still assembling. We’re not just measuring where things are; we’re witnessing when they were.

The cosmic microwave background (CMB) is the extreme case: light from 380,000 years after the Big Bang, traveling for 13.8 billion years. When we observe the CMB, we see the universe as a baby—the most ancient light in existence.

1.6 Closing: From Spoilers to Understanding

Let’s recap what we’ve covered:

The thesis: Pretty pictures → measurements → models → inferences

The method: - We measure four types of things: brightness, position, wavelength, timing - Everything else is inferred using physical models - Physics provides relationships; math makes them precise and testable

The key physics of light: - Speed: \(c = 3 \times 10^{10}\) cm/s (finite, constant) - Wave relation: \(c = \lambda \nu\) (longer λ ↔︎ lower ν) - Photon energy: \(E = h\nu = hc/\lambda\) (shorter λ → higher E) - The appearance of \(h\) signals quantum mechanics - Different wavelengths probe different temperatures/processes - Finite light speed → lookback time

The spoiler reel demonstrated: - Colors encode atoms (nebulae) - Brightness enables distance (ladder) - Spectra reveal origin (elements) - Spectroscopy is foundational (prism) - EM spectrum maps conditions (temperature ladder) - Wavelength choice reveals components (M51, Pillars, Crab)

Where We’re Headed

| Module | Big Question | Key Tools |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | How do we measure stars? | Distance, luminosity, temperature, spectra, H-R diagram |

| 2 | How do stars live and die? | Nuclear physics, stellar structure, remnants |

| 3 | Where do stars come from? | ISM, star formation, planets |

| 4 | How does the universe work? | Galaxies, dark matter, cosmology |

Today’s spoilers touched all four modules. Now we build the tools to understand them.

Next class: The Math Boot Camp—units, scaling, order-of-magnitude estimation, and the ratio method. Not hazing; tools that make precise reasoning possible.

Coming soon: Our first real inference problem: How do we measure distance to objects we can’t reach?

Today you saw the spoilers. Now we build the tools to understand them—one inference at a time.

“Astronomy is just looking through telescopes.”

Many imagine astronomers peering through eyepieces all night. Modern astronomy is almost entirely data analysis. Telescopes collect photons automatically; astronomers write code to analyze the resulting datasets.

You’ll spend far more time with equations, graphs, and reasoning than with eyepieces. That’s where the real discovery happens.

Self-Assessment Checklist

✅ Section 1.1: The Course Thesis

✅ Section 1.2: The Spoiler Reel

✅ Section 1.3: The Decoder Ring

✅ Section 1.4: Light as Messenger

✅ Section 1.5: Lookback Time

All boxes checked? You’re ready for the Math Boot Camp!

Some unchecked? Review those sections—these ideas are the foundation.

Quick Practice

Use these as a fast warm-up. Keep answers short but explicit about what was measured vs what was inferred.

- An Astro 101 student says “astronomy is about looking at pretty space pictures.” How would you correct them using the framework from this lecture?

- A news headline reads “Scientists measure the mass of a distant black hole.” What did they actually measure, and what model connected that measurement to mass?

- If you double a photon’s wavelength, what happens to its energy? Explain using \(E = hc/\lambda\).

- The Andromeda Galaxy is 2.5 million light-years away. When you observe it tonight, are you seeing it as it is now? Explain.

- We measure photons (brightness, position, wavelength, timing) and infer physical properties using models; pictures are data, not answers.

- They measured motion (e.g., Doppler shifts or orbital periods). The gravity/orbit model converts motion into mass.

- Energy is inversely proportional to wavelength, so doubling \(\lambda\) halves \(E\).

- You see Andromeda as it was 2.5 million years ago; lookback time equals distance in light-years.

Practice Problems

Conceptual

- The measurement ceiling. A student lists luminosity, temperature, mass, and distance as the four things astronomers directly measure. Correct this statement. What can astronomers directly measure, and how do we actually determine each item on the student’s list?

- Standard candle logic. Explain why a standard candle must be both intrinsically luminous enough and reliably calibrated. What goes wrong if either condition fails?

- Observable vs. model-dependent (HW1). A news article claims “Astronomers measured the temperature of TRAPPIST-1e to be 255 K.” Critique this statement. What was actually measured, and what model was used to arrive at the temperature?

- Empirical vs. physical (HW1). What is the difference between an empirical law and a physical law? Give one example from Lecture 1 where an empirical pattern is explained by a physical mechanism, and explain why that distinction matters.

Calculation

- 21-cm hydrogen line. The 21-cm line traces cold neutral hydrogen.

- Convert 21 cm to meters and to nanometers.

- Compute the frequency using \(c = \lambda \nu\) with \(c = 3 \times 10^{10}\) cm/s.

- Show a unit check that gives s\(^{-1}\).

- Limiting case: X-rays have \(\lambda \sim 10^{-8}\) cm. Without calculating, predict whether their frequency is higher or lower than 21-cm radiation, and by roughly how many orders of magnitude.

- Inverse-square distance. Two identical Cepheid variables are observed. Star A has flux 25 times greater than Star B.

- Derive the distance ratio \(d_B/d_A\).

- If Star A is at 1 kpc, what is Star B’s distance in kpc?

- Convert Star B’s distance to light‑years (1 pc \(\approx 3.26\) ly).

- Light-travel across the galaxy. The Milky Way is about 100,000 light-years across.

- How long does light take to cross it? Express in years.

- Convert this to seconds using 1 year \(\approx 3.15 \times 10^7\) s.

- Sanity check: The Sun orbits the Galactic center in ~230 million years. Roughly how many galactic orbits occur during one light‑crossing time?

Synthesis

- The inference chain. For each scenario, identify (a) what is directly measured, (b) what model connects measurement to inference, and (c) what is inferred:

- Determining the composition of the Sun

- Determining the mass of a planet orbiting another star

- Determining the age of a star cluster

- The measurement-inference web. A star is reported to have mass \(\sim 15\,M_\odot\), radius \(\sim 900\,R_\odot\), luminosity \(\sim 10^5\,L_\odot\), and distance \(\sim 650\) light-years.

- For each property, identify which observable(s) are needed to infer it.

- Which properties depend on knowing the others first?

- If the distance were revised upward by 20%, which inferences would change and how?