Lecture 4: Light as Information

How Photons Encode the Universe

Learning Objectives

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

- Describe the electromagnetic spectrum and relate wavelength, frequency, and photon energy

- Identify the key ways light interacts with matter (absorption, emission, transmission, reflection, refraction, and scattering) and give astronomical examples

- Explain Rayleigh scattering qualitatively (blue skies, red sunsets)

- Explain what a blackbody is and interpret the Planck spectrum qualitatively

- Identify limiting cases of the Planck function (Rayleigh-Jeans, Wien tail)

- Use Wien’s law to estimate temperature from peak wavelength

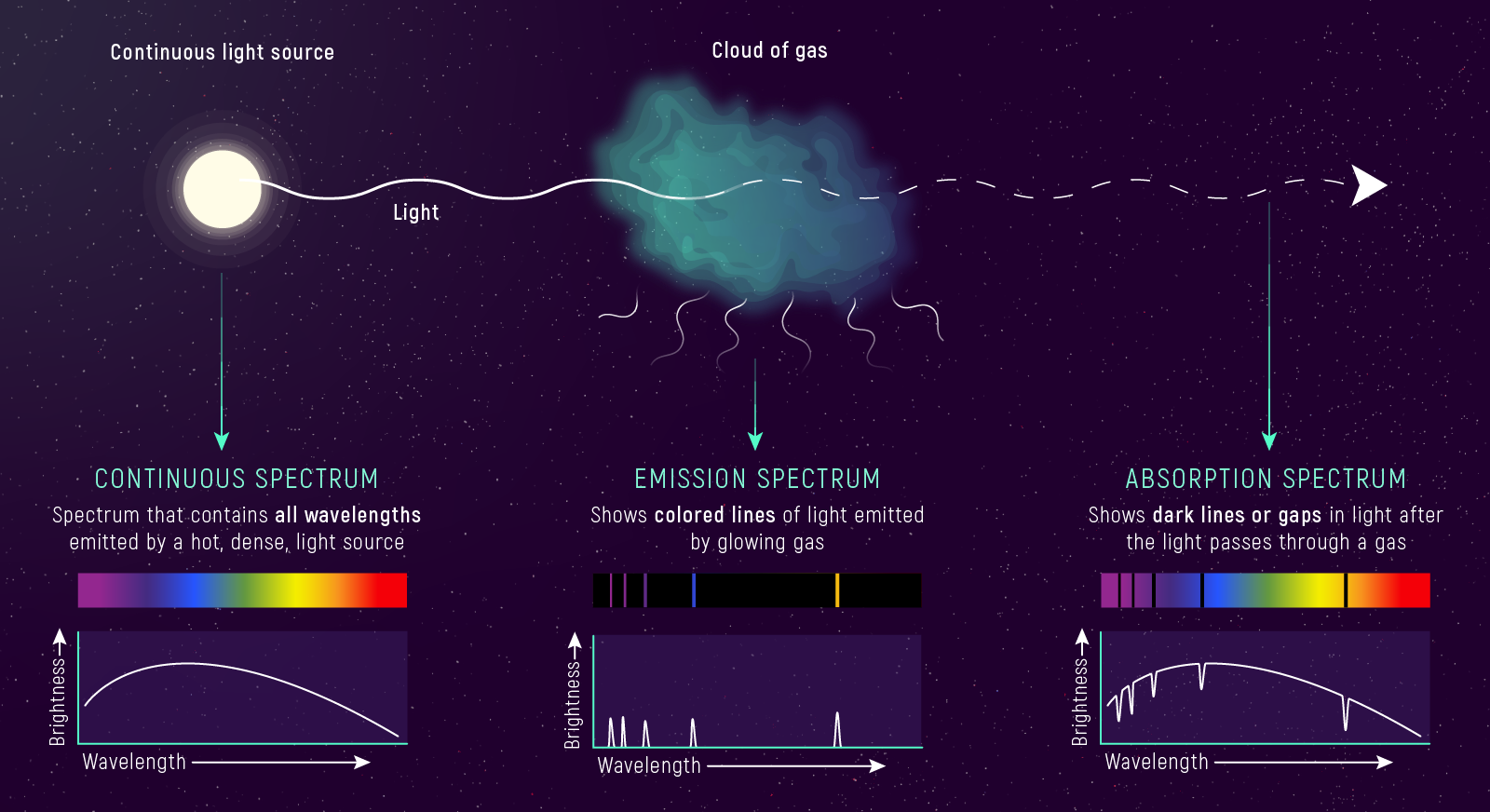

- Distinguish continuous, absorption, and emission spectra (Kirchhoff’s laws)

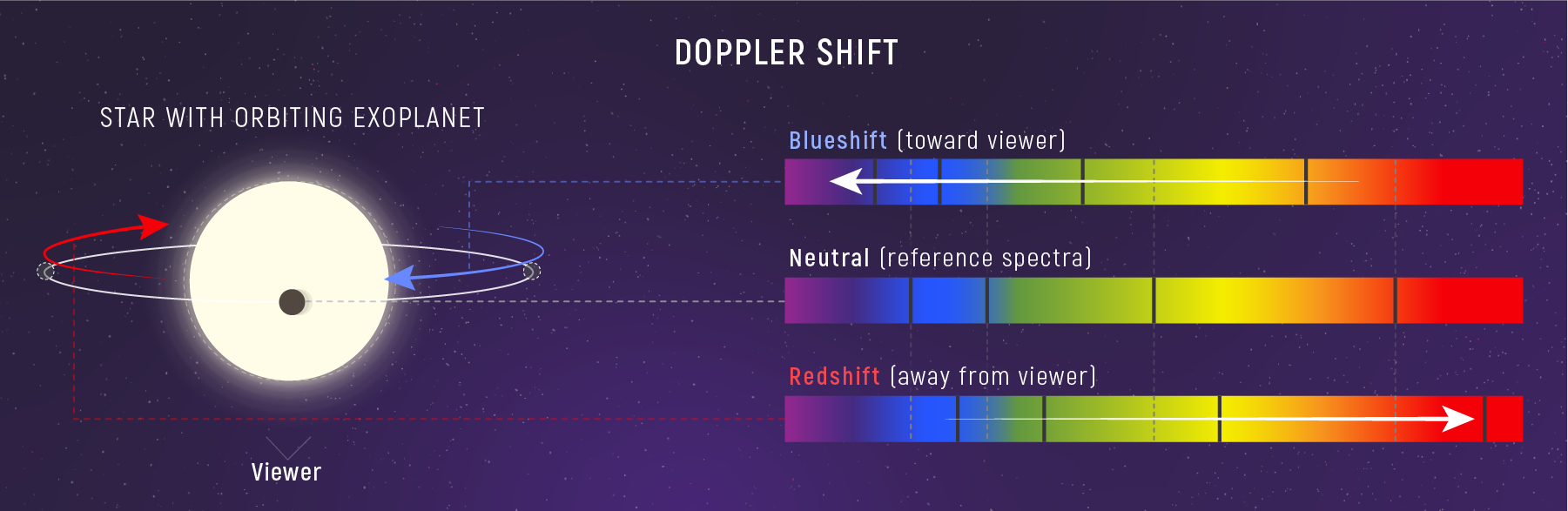

- Explain Doppler shift qualitatively and connect line shifts to radial motion

- Apply telescope scaling relations for collecting area (\(\propto D^2\)) and angular resolution (\(\propto \lambda/D\))

Concept Throughline

Light is a messenger that carries encoded physics. By understanding how objects emit and absorb light, we can infer their properties — starting with temperature — without ever visiting them.

Color encodes temperature. A star’s color tells you its surface temperature through Wien’s displacement law: hotter objects peak at shorter (bluer) wavelengths, cooler objects at longer (redder) wavelengths. In practice we correct for dust reddening and remember stellar atmospheres add spectral lines — but the blackbody shape is still the starting model.

What You Can Infer After This Reading

- Use the continuum shape to infer temperature.

- Use absorption and emission lines to infer composition.

- Use line shifts to infer line-of-sight motion.

- Use telescope scalings to infer faintness reach and angular detail.

Part 1: Why Light Matters

The Astronomer’s Dilemma

Look up on a clear night. Every point of light you see is a message from across space and time. But what does that message contain?

In Lecture 1, we learned that astronomers can directly measure only four things: brightness, position, wavelength, and timing. Everything else — temperature, mass, radius, age, composition — must be inferred. Today we begin building the inference toolkit, starting with the question: what can we learn from a star’s color?

The answer turns out to involve one of the most important developments in physics: the birth of quantum mechanics. Max Planck’s attempt to explain how hot objects glow led to a revolution that reshaped our understanding of the universe. And the equation he derived — the Planck function — remains the foundation of stellar astrophysics.

What You’ll Gain

By the end of this reading, you’ll be able to look at a star and estimate its surface temperature from its color. You’ll understand why hot stars are blue and cool stars are red. And you’ll have your first encounter with a professional-grade physics equation — the Planck function — along with strategies for making such equations less intimidating.

Part 2: The Electromagnetic Spectrum

Unit convention: We’ll use cgs units throughout (cm, s, erg, K). For convenience, optical/UV wavelengths will often be written in nm, where \(1\ \text{nm} = 10^{-7}\ \text{cm}\).

Light as a Wave

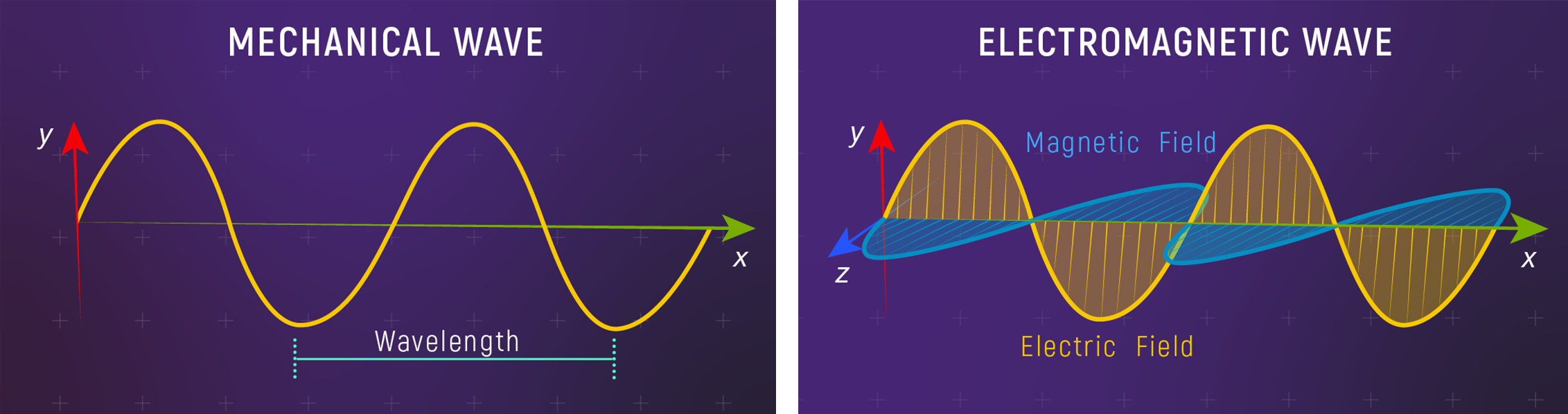

Light is an electromagnetic wave — oscillating electric and magnetic fields that propagate through space at a constant speed.

What to notice: Mechanical waves need a medium (water, air); EM waves don’t. Light travels through the vacuum of space—no medium required. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

Unlike mechanical waves (water ripples, sound, a vibrating string), electromagnetic waves don’t need a medium. A water wave is the water moving up and down; a sound wave is air molecules compressing and expanding. But light travels perfectly well through the vacuum of space — no water, no air, no “stuff” required. What’s oscillating are the electric and magnetic fields themselves.

Both wave types share the same vocabulary:

Wavelength (\(\lambda\)): The distance between successive wave crests. For a water wave, you could measure this with a ruler. For light, wavelengths range from kilometers (radio) down to sub-atomic scales (gamma rays). Optical and UV wavelengths are often written in nanometers (nm), where \(1\ \text{nm} = 10^{-7}\ \text{cm} = 10^{-9}\ \text{m}\).

The nanometer (nm) is a unit of length equal to \(10^{-9}\) m = \(10^{-7}\) cm. It’s roughly 10 times the diameter of a hydrogen atom and is convenient for optical and UV wavelengths. Visible light spans about 400–700 nm.

Frequency (\(\nu\)): The number of oscillations per second, with units s\(^{-1}\) (also called Hertz, Hz). If you watch a fixed point and count how many wave crests pass per second, that’s the frequency.

Speed (\(c\)): In vacuum, all electromagnetic waves travel at \(c = 2.998 \times 10^{10}\ \text{cm/s}\) — the speed of light.

These three quantities are related by the fundamental wave equation:

\[ c = \lambda \nu \tag{1}\]

Wave relation (speed, wavelength, frequency)

What it predicts

Given any two of \(c\), \(\lambda\), \(\nu\), it predicts the third.

What it depends on

\(\lambda \propto \nu^{-1}\) (inverse relationship at fixed \(c\)).

What it's saying

Wavelength and frequency are two ways of describing the same wave; longer wavelength means lower frequency.

Assumptions

- Light travels in vacuum at speed \(c\)

- Applies to all electromagnetic radiation

See: the equation

Let’s unpack this equation:

- What it predicts: The speed of a wave given its wavelength and frequency

- What it depends on: \(\lambda\) (wavelength) and \(\nu\) (frequency)

- The story: All EM waves travel at the same speed \(c\) in vacuum; they differ only in how they trade off between wavelength and frequency

- Units check: \([\text{cm/s}] = [\text{cm}][\text{s}^{-1}]\) ✓

This means if you know any two, you can calculate the third. Since \(c\) is constant, wavelength and frequency are inversely related: \(\nu \propto \lambda^{-1}\). Long wavelength means low frequency, short wavelength means high frequency.

Throughout this course, we write inverse relationships using negative exponents:

| Fraction notation | Exponent notation | Both mean… |

|---|---|---|

| \(\nu = c/\lambda\) | \(\nu = c\lambda^{-1}\) | \(\nu \propto \lambda^{-1}\) |

| \(E = hc/\lambda\) | \(E = hc\lambda^{-1}\) | \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\) |

| \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = b/T\) | \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = bT^{-1}\) | \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\) |

Why bother? The exponent notation makes proportional reasoning instant:

- See \(T^{-1}\)? Temperature is in the denominator — they’re inversely related.

- See \(D^{2}\)? Diameter is squared — quadratic scaling.

- See \(\lambda^{-4}\)? Wavelength to the fourth power in the denominator — very steep!

This notation is standard in upper-division physics. Getting comfortable with it now will pay off later.

Wave equation: \(c = \lambda\nu\), so \(\nu = c\lambda^{-1}\)

- If wavelength doubles, frequency ___?

- If frequency triples, wavelength ___?

- Radio waves have \(\lambda \sim 1\) cm; visible light has \(\lambda \sim 5\times10^{-5}\) cm. How do their frequencies compare?

- Halves (\(\times \frac{1}{2}\)) — frequency is inversely proportional to wavelength

- Decreases to \(\frac{1}{3}\) — same inverse relationship

- Visible light has \(\sim 20{,}000\times\) higher frequency — because its wavelength is \(\sim 20{,}000\times\) shorter

The Spectrum: From Radio to Gamma

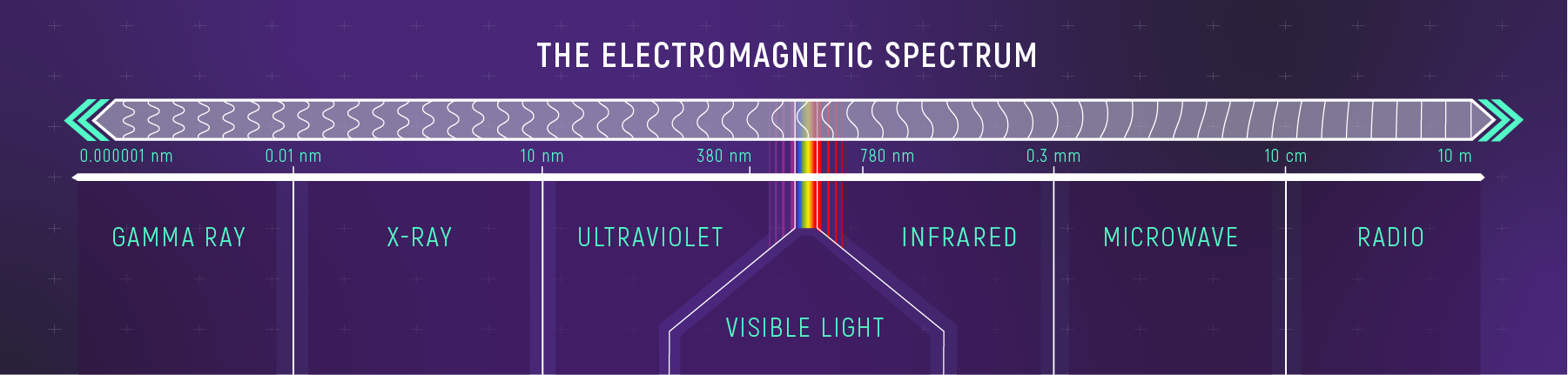

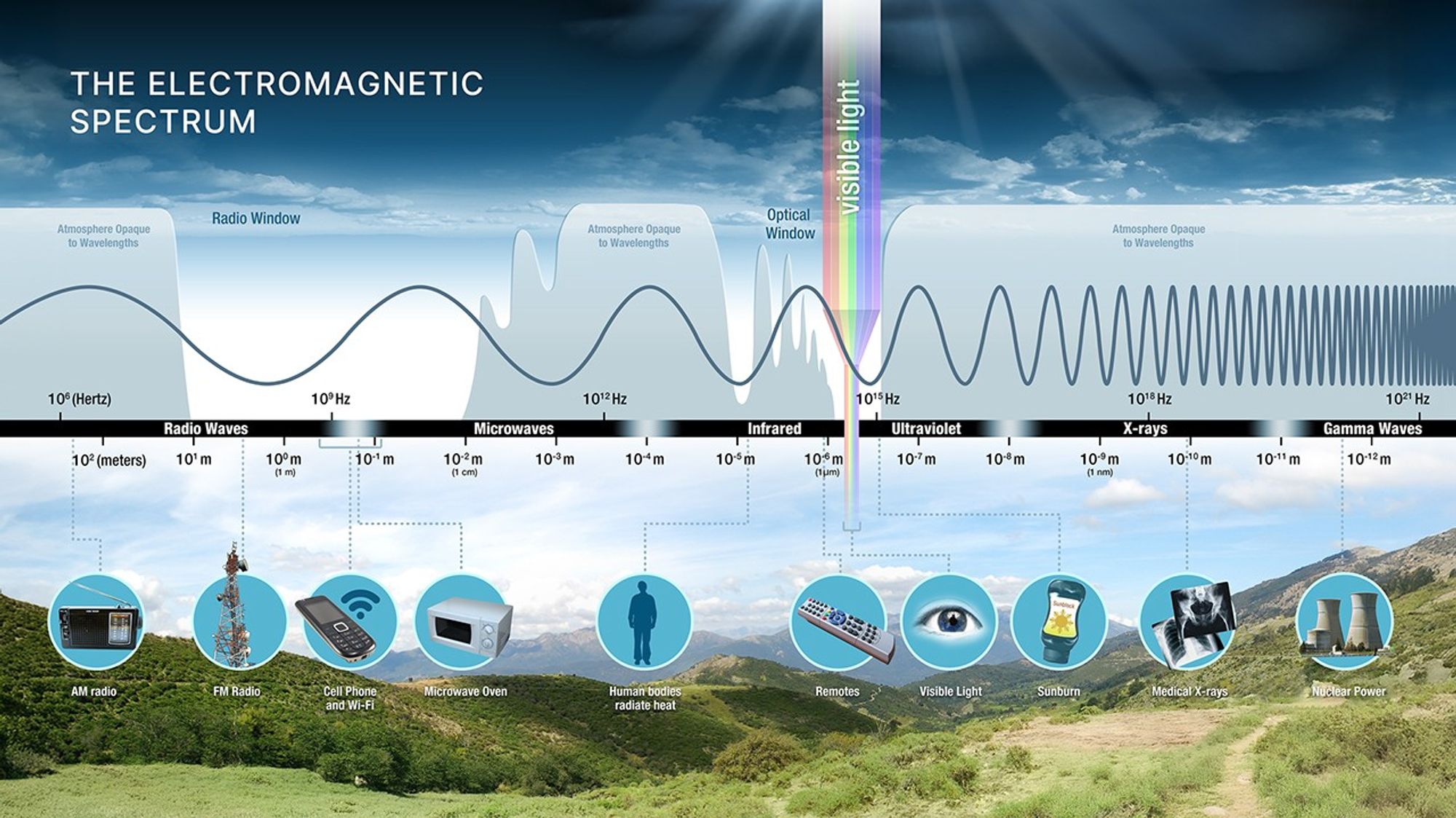

The electromagnetic spectrum spans an enormous range of wavelengths, from radio waves with wavelengths of centimeters and longer down to sub-atomic scales (gamma rays). We divide this spectrum into named bands:

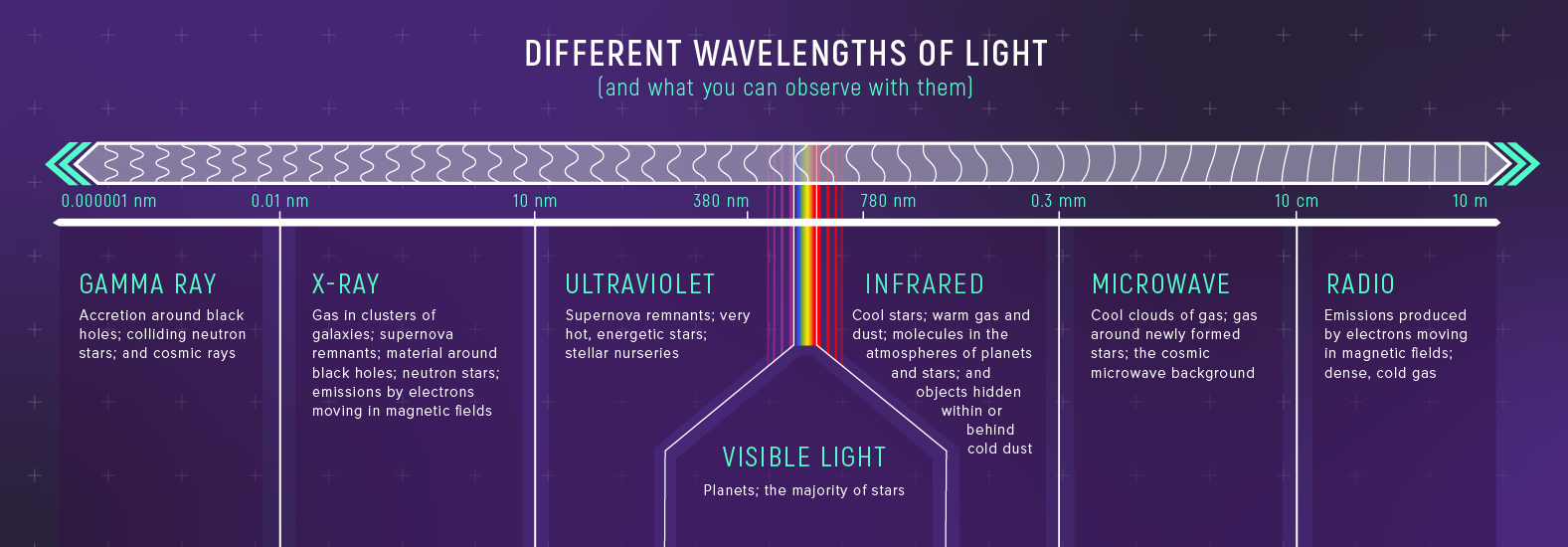

What to notice: The EM spectrum spans from gamma rays (≈ \(10^{-13}\) cm) to radio waves (≈ \(10^{3}\) cm). Visible light is a tiny sliver—400 to 700 nm. Different wavelengths = different physics revealed. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

| Band | Wavelength Range | What It Reveals |

|---|---|---|

| Radio | \(> 1\) cm | Cold gas, magnetic fields, pulsars |

| Microwave | \(0.1\) – \(1\) cm | CMB, molecular clouds |

| Infrared | \(700\) nm – \(0.1\) cm | Warm dust, cool stars, exoplanets |

| Visible | \(400\) – \(700\) nm | Stellar surfaces, nebulae |

| Ultraviolet | \(10\) – \(400\) nm | Hot stars, active galactic nuclei |

| X-ray | \(0.01\) – \(10\) nm | Million-degree plasma, accretion disks |

| Gamma | \(< 0.01\) nm | Extreme events: supernovae, GRBs |

Key insight: Different wavelengths reveal different physics. A galaxy looks completely different in radio vs. X-rays because you’re seeing different physical components — cold gas vs. hot plasma. This is why astronomers build telescopes for every part of the spectrum.

What to notice: Different wavelengths reveal different cosmic phenomena. Gamma rays see black holes; X-rays see hot plasma; visible shows stars; infrared penetrates dust; radio maps cold gas. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

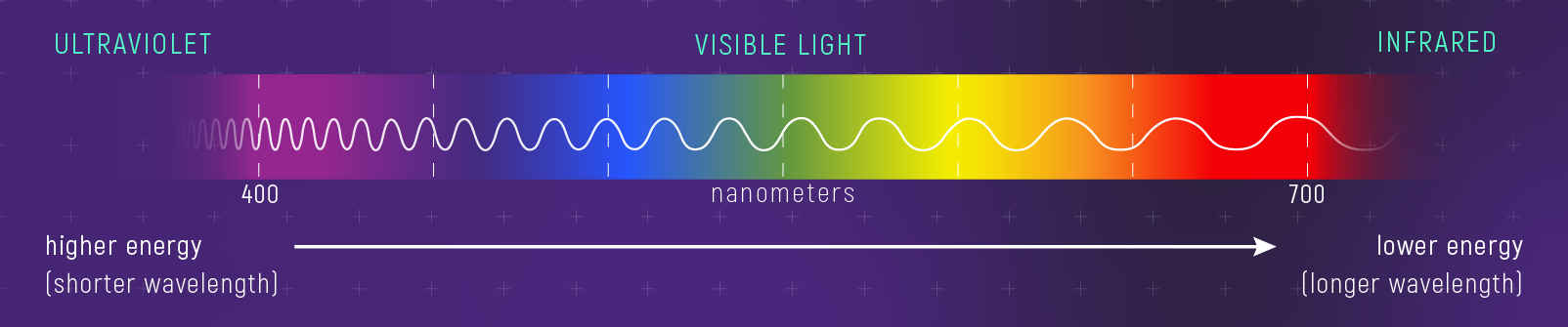

Light as Particles: Photon Energy

Light also behaves as particles called photons. Each photon carries a discrete amount of energy given by:

\[ E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1} \tag{2}\]

Photon energy (Planck relation)

What it predicts

Given wavelength \(\lambda\) (or frequency \(\nu\)), it predicts the energy \(E\) of a single photon.

What it depends on

\(E \propto \nu\) and \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\).

What it's saying

Shorter wavelength = higher energy photon. The constant \(h\) signals quantum mechanics is at work.

Assumptions

- Light comes in discrete packets (photons)

- Each photon carries energy proportional to its frequency

- This is a quantum mechanical result—classical physics cannot predict it

See: the equation

where \(h = 6.626 \times 10^{-27}\) erg·s is Planck’s constant.

Let’s unpack this equation:

- What it predicts: The energy carried by a single photon

- What it depends on: Either frequency (\(\nu\)) or wavelength (\(\lambda\)) — your choice, since they’re related by \(c = \lambda\nu\)

- The story: \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\) — shorter wavelength means higher energy. This is why gamma rays can damage DNA while radio waves pass harmlessly through your body.

- Units check: \([E] = [\text{erg·s}][\text{s}^{-1}] = \text{erg}\) ✓

What to notice: Short wavelength = high energy = high frequency. The wave ‘crests’ are closer together for blue/UV light than for red/IR light. E = hc/λ quantifies this. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

\[[E] = \frac{[\text{erg·s}][\text{cm/s}]}{[\text{cm}]} = \frac{\text{erg·cm}}{\text{cm}} = \text{erg}\ \checkmark\]

Units work out. This is always worth checking.

Photon energy: \(E = hc\lambda^{-1}\)

- If wavelength doubles, photon energy ___?

- If wavelength is halved, photon energy ___?

- A photon has \(\lambda = 200\) nm. Another has \(\lambda = 800\) nm. How do their energies compare?

- Halves (\(\times \frac{1}{2}\)) — energy is inversely proportional to wavelength

- Doubles (\(\times 2\)) — halving \(\lambda\) doubles \(E\)

- The 200 nm photon has \(4\times\) more energy: \(E_{200}/E_{800} = \lambda_{800}/\lambda_{200} = 800/200 = 4\). This is why UV causes sunburns but red light doesn’t.

The fact that photon energy depends on wavelength (\(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\)) explains why atoms absorb and emit at specific wavelengths. An atom can only absorb a photon if its energy matches the gap between two allowed energy levels. This connects Part 2 (photons) directly to Part 6 (spectral lines) — and it’s why Planck’s quantum hypothesis was revolutionary.

Before reading further: Why do you think the sky looks blue during the day but red/orange at sunset?

(Hint: same atmosphere, same sunlight — what’s different?)

Part 3: How Light Interacts with Matter

So far, we’ve treated light as something that simply travels through space. But the reason light carries information is that it doesn’t just travel — it interacts.

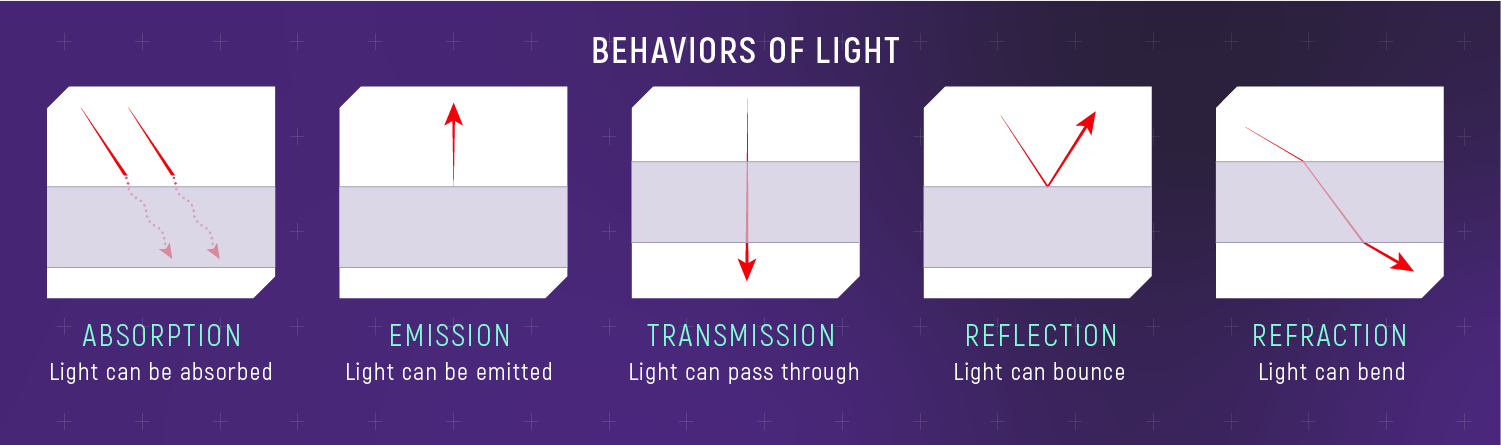

When light meets matter, the fundamental interactions are absorption, emission, and scattering. When you zoom out to what happens to a beam at a boundary, we describe the outcomes as transmission (it gets through), reflection (it bounces), and refraction (it bends). Every spectrum you will ever interpret is some combination of these processes.

Five Macroscopic Outcomes (Plus Scattering)

We’ll list five common outcomes (absorption, emission, transmission, reflection, refraction) and then treat scattering separately because it is a major astrophysical effect with a distinctive wavelength dependence.

Absorption

When a photon is absorbed, it is destroyed and its energy goes into the material — often as heat, or by exciting an electron to a higher energy level.

Absorption is selective: materials absorb some wavelengths more strongly than others. That selectivity is what turns a smooth spectrum into a spectrum with informative “missing” wavelengths.

Emission

Emission is absorption’s partner. When matter loses energy, it can create a new photon and send it out into space.

The important point is not “hot things glow” (though they do), but what sets the photon’s wavelength: the photon energy must match the energy the material is losing. This is why atoms produce spectral lines at specific wavelengths.

Transmission

Transmission happens when light passes through material without being absorbed. Glass transmits visible light but absorbs much of the ultraviolet; Earth’s atmosphere transmits visible and parts of the radio, but absorbs most X-rays.

What to notice: Earth’s atmosphere has two main ‘windows’ — radio and optical — where it’s transparent. Most UV, X-rays, and gamma rays are blocked, which is why we need space telescopes for those wavelengths. (Credit: NASA)

This is why “what wavelength?” is never an abstract question in astronomy — it determines what can be observed from the ground and what requires a space telescope.

Transmission windows determine what can reach your detector — and when you need a telescope in space.

Reflection

Reflection is light bouncing off a surface. Planets are visible in reflected starlight, and the fraction reflected (the albedo) encodes information about surface composition and texture.

Refraction

Refraction is bending when light moves from one medium to another (air → glass, for example). Lenses focus light by refraction. Earth’s atmosphere also refracts starlight, and turbulent refraction is part of why stars appear to “twinkle.”

Refraction is wavelength-dependent: blue light bends slightly more than red. This is why prisms spread white light into a spectrum.

What to notice: Light can be absorbed, emitted, transmitted, reflected, or refracted. Each interaction encodes information about the material. Blackbodies absorb all wavelengths (no reflection). (Credit: JWST/STScI)

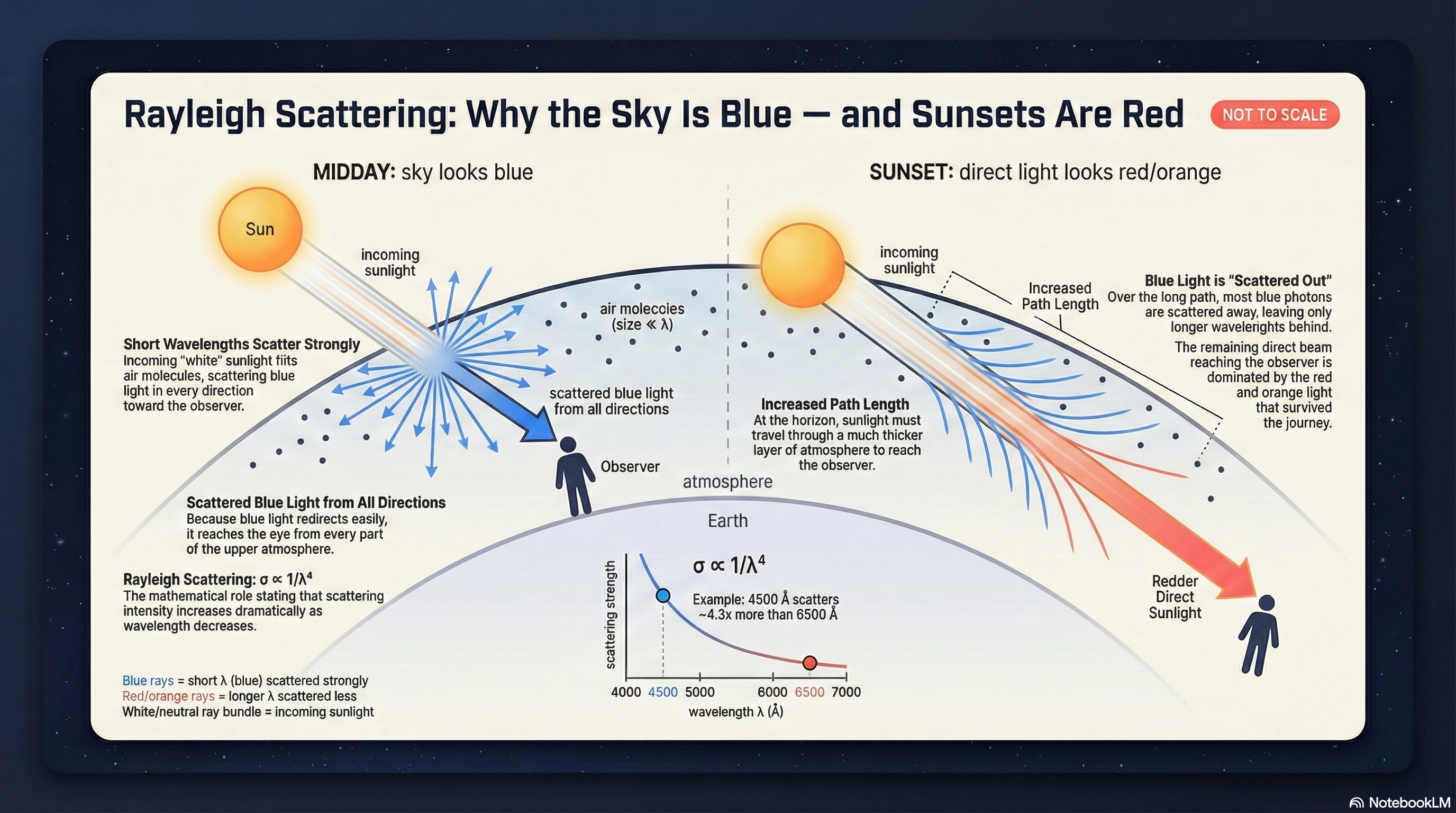

Scattering: Blue Skies and Red Sunsets

Scattering is what happens when light is redirected into new directions. When the particles doing the scattering are much smaller than the wavelength of the light (like air molecules), we get Rayleigh scattering.

\[ \sigma_{\mathrm{Rayleigh}} \propto \lambda^{-4} \tag{3}\]

Rayleigh scattering (wavelength dependence)

What it predicts

How the strength of scattering depends on wavelength for particles much smaller than the wavelength.

What it depends on

Scales as \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\).

What it's saying

Short wavelengths scatter much more strongly than long wavelengths, which is why blue light is scattered more than red light.

Assumptions

- Particle size \(\ll \lambda\) (Rayleigh regime)

- Elastic scattering (photon energy unchanged)

See: the equation

The \(\lambda^{-4}\) dependence is steep. Blue light (\(\lambda \approx 450\ \text{nm} = 4.5\times10^{-5}\ \text{cm}\)) scatters about \((650/450)^4 \approx 4\) times more than red light (\(\lambda \approx 650\ \text{nm} = 6.5\times10^{-5}\ \text{cm}\)). Because \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\), shorter wavelength means larger scattering cross-section, so write the ratio as \[\frac{\sigma_{450}}{\sigma_{650}} = \left(\frac{650}{450}\right)^4.\]

Why the Sky Is Blue

Sunlight enters the atmosphere and encounters countless N\(_2\) and O\(_2\) molecules. Short wavelengths scatter strongly in all directions, so when you look up away from the Sun, much of what you’re seeing is scattered blue light coming toward you from all over the sky.

Why Sunsets Are Red

At sunset, sunlight travels through much more atmosphere before reaching your eyes. Along that long path, the blue light is preferentially scattered out of the direct beam. The light that continues forward is therefore redder.

Same physics, different geometry: at noon the path is short and you see a white Sun plus a blue sky; at sunset the path is long and you see a red Sun plus enhanced reds/oranges in the transmitted light.

What to notice: Rayleigh scattering explains both the blue sky (scattered short wavelengths) and red sunsets (transmitted long wavelengths). Same physics, different viewing geometry. (Credit: NotebookLM)

Twinkling (scintillation) is caused mainly by turbulent refraction in Earth’s atmosphere, not Rayleigh scattering. Different pockets of air act like weak, shifting lenses that rapidly bend starlight.

Why don’t planets twinkle as much? Planets are tiny disks, not perfect point sources. The random bending averages out across the disk.

Dust between stars can also remove blue light more efficiently than red light. The result is that distant stars can appear redder than they truly are. Correcting for this effect is part of doing precision astronomy.

Rayleigh scattering: \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\)

- If wavelength doubles, scattering cross-section ___?

- Blue light (\(\lambda \approx 450\) nm) vs. red light (\(\lambda \approx 650\) nm): which scatters more, and by what factor?

- If you could see in the infrared (\(\lambda \approx 1000\) nm), would the sky appear more blue or less blue than in visible light?

- Decreases by \(2^4 = 16\times\) — the \(\lambda^{-4}\) dependence is steep!

- Blue scatters \((650/450)^4 \approx 4\times\) more than red

- Much less blue — longer wavelengths scatter far less, so the sky would appear darker/grayer in the IR

The \(\lambda^{-4}\) dependence of scattering explains why astronomers build infrared telescopes. Dust grains in star-forming regions scatter and absorb visible light, hiding newborn stars. But infrared light (\(\lambda \sim 1\)–\(10\ \mu\)m) passes through with far less attenuation — at 2 μm, scattering is \((0.5/2)^4 = 1/256\) as strong as at visible wavelengths. JWST’s infrared capability isn’t just a technical choice; it’s dictated by the physics of light-matter interaction.

Opacity and “How Far Light Gets”

In astronomy, we often care less about “what is an object made of?” and more about “how far can photons travel before they get absorbed or scattered?”

That idea is captured by opacity: how strongly matter blocks light at a particular wavelength. Opacity is usually highly wavelength-dependent. A cloud of gas might be transparent in the optical but opaque in the ultraviolet; a dust cloud might block visible light but transmit infrared.

In Module 2, we’ll use this to understand a key idea: we only see to the depth where the material becomes optically thick. For a star, that boundary is the photosphere — the place where photons last scattered before escaping to space.

Quick Checks: Light and Matter

Question: Why is the daytime sky blue, but the setting Sun looks red?

Answer: Rayleigh scattering is stronger at short wavelengths. In the daytime sky you’re seeing scattered blue light from all directions. At sunset the sunlight travels through a longer path, so much of the blue is scattered out of the direct beam and the transmitted light that reaches you is redder.

Question: If Earth’s atmosphere were twice as thick, would sunsets be redder or less red?

Answer: Redder. A longer/denser path means more scattering removes more blue light from the direct beam.

Question: You observe two identical stars — one nearby, one far away behind interstellar dust. Which appears redder?

Answer: The distant star behind the dust. Dust removes/scatters short wavelengths more efficiently, so the transmitted light is redder.

Part 4: Blackbody Radiation

What Is a Blackbody?

A blackbody is an idealized object that absorbs all electromagnetic radiation that falls on it — no reflection, no transmission. When heated, a blackbody re-emits radiation with a spectrum that depends only on its temperature.

In the language of Part 3, a blackbody is the “absorption extreme”: no reflection, no transmission — just absorption and thermal emission.

The name “blackbody” is somewhat misleading. A cold blackbody would indeed appear black (it absorbs everything and emits very little). But a hot blackbody glows — the hotter it is, the brighter and bluer it glows.

Why blackbodies matter for astronomy: Stars are approximate blackbodies. Their spectra deviate due to absorption lines (which we’ll study in Module 2), but the overall shape follows the blackbody curve. Understanding blackbody radiation is therefore fundamental to stellar astrophysics.

Other astronomical blackbodies include:

- Planets: Earth emits thermal radiation approximately as a blackbody at ~255 K (infrared)

- The Cosmic Microwave Background: The most perfect blackbody ever measured, at 2.725 K

- Accretion disks: Hot gas falling into black holes radiates thermally

The Planck Spectrum: Qualitative Picture

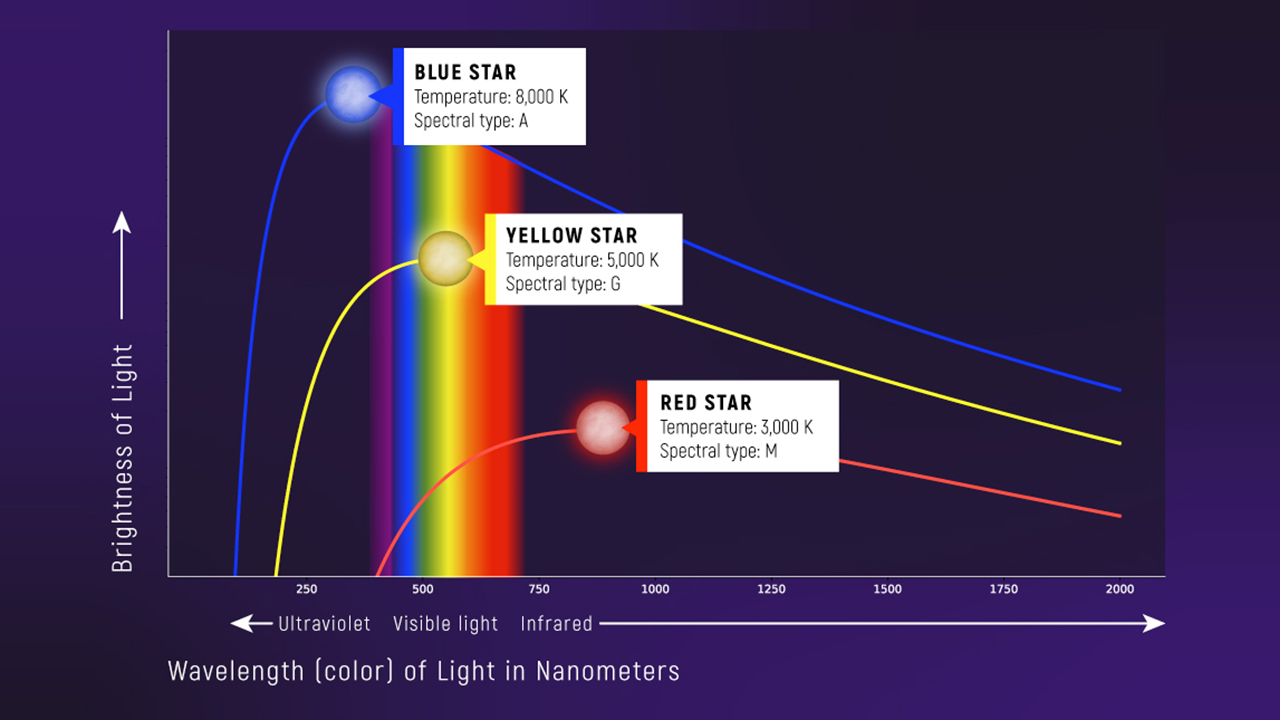

When you heat an object, it glows. The color of that glow depends on temperature:

- A stovetop burner glows dull red (~700 K)

- An incandescent bulb filament glows yellow-white (~2700 K)

- The Sun’s surface glows yellow (~5800 K)

- A welding arc glows blue-white (~6000+ K)

What to notice: Hotter stars peak at shorter wavelengths (bluer) AND emit more total light. A blue 8000 K star peaks near \(\\lambda_{\\mathrm{peak}}\\approx 360\\ \\mathrm{nm}\); a red 3000 K star peaks near \(970\\ \\mathrm{nm}\). Wien’s law: \(\\lambda_{\\mathrm{peak}} = b/T\) with \(b = 0.2898\) cm·K. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

The figure shows blackbody spectra (called Planck curves) at three different temperatures. Notice two patterns:

The peak shifts to shorter wavelengths as temperature increases. Hot objects peak in the blue/UV; cool objects peak in the red/infrared.

The total energy emitted increases dramatically with temperature. The area under the curve (total power radiated) grows as \(T^4\) — we’ll quantify this with the Stefan-Boltzmann law in Module 2.

Question: A star’s Planck curve peaks in the infrared at 900 nm. Is this star hotter or cooler than the Sun (which peaks at \(\sim 500\) nm)?

Answer: Cooler. Peak wavelength is inversely related to temperature (\(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\)). Longer peak wavelength means lower temperature. This star is roughly \(500/900 \approx 0.6\times\) the Sun’s temperature, or about 3200 K.

Before reading further, think about this:

Look at the blackbody curves in the figure. The blue star (8000 K) peaks in the ultraviolet. Why does it still appear blue to our eyes, rather than invisible?

The red star (3000 K) peaks in the infrared. Why does it still glow visibly red?

(Think about the shape of the Planck curve, not just the peak location.)

The Ultraviolet Catastrophe: When Classical Physics Failed

Before 1900, physicists tried to derive the blackbody spectrum using classical physics. The result was the Rayleigh-Jeans law:

\[B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\]

This works well at long wavelengths. But notice the problem: as \(\lambda \to 0\), the intensity goes to infinity! Classical physics predicted that any warm object should emit infinite energy in the ultraviolet and beyond.

This was called the ultraviolet catastrophe — a fundamental failure of classical physics. Ovens don’t emit infinite UV radiation. Something was deeply wrong with the classical picture of how light and matter interact.

Planck’s Quantum Solution

In 1900, Max Planck found the solution — though he called it “an act of desperation.” He proposed that energy is emitted in discrete packets called quanta, with energy:

\[E = h\nu\]

This changes everything at short wavelengths. To emit a high-frequency (short-wavelength) photon, an oscillator needs energy \(h\nu\). If the thermal energy available (\(\sim k_B T\)) is less than \(h\nu\), emission is suppressed. You can’t emit a fraction of a photon.

This quantum suppression cuts off the ultraviolet catastrophe and produces the correct blackbody spectrum.

Historical note: Planck didn’t fully believe his own solution — he hoped someone would find a classical explanation. It took Einstein (1905) to take quanta seriously, showing that light itself comes in discrete packets (photons) when explaining the photoelectric effect. This quantum revolution, born from trying to understand hot glowing objects, reshaped all of physics.

Planck’s quantum hypothesis doesn’t just fix the UV catastrophe — it’s the foundation for understanding why atoms have discrete energy levels (Part 6), why spectral lines exist, and ultimately why stars don’t collapse (electron degeneracy pressure in Module 2). The same constant \(h\) that appears here will reappear when we discuss stellar structure, white dwarfs, and neutron stars. Quantum mechanics isn’t an add-on to astrophysics; it’s woven into the fabric.

The Planck Function: Meeting a Real Equation

The complete blackbody spectrum is given by the Planck function:

\[B_\lambda(T) = \frac{2hc^2}{\lambda^5} \frac{1}{e^{hc/\lambda k_B T} - 1}\]

This looks intimidating. Don’t panic. Let’s break it down piece by piece:

For this course, you do not need to compute \(B_\lambda\) from scratch. You need to recognize the shape and know which term controls which regime: the \(\lambda^{-5}\) factor would drive short wavelengths up, but the exponential term suppresses them at high photon energy.

From here on I’m using cgs units (erg, cm), which are still common in astrophysics. The physics is identical; only the unit choices change.

What is spectral radiance? The Planck function \(B_\lambda(T)\) gives the spectral radiance — the power emitted per unit area, per unit solid angle, per unit wavelength interval. It tells you how much energy flows out of each square centimeter of surface, in each direction, at each wavelength. If “per steradian” feels abstract, think “per direction”: \(B_\lambda\) tells you how bright a surface looks in a given direction at each wavelength.

| Symbol | Meaning | Value / Units |

|---|---|---|

| \(B_\lambda(T)\) | Spectral radiance at wavelength \(\lambda\) and temperature \(T\) | erg s\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-2}\) sr\(^{-1}\) cm\(^{-1}\) |

| \(h\) | Planck’s constant | \(6.626 \times 10^{-27}\) erg·s |

| \(c\) | Speed of light | \(2.998 \times 10^{10}\) cm/s |

| \(k_B\) | Boltzmann’s constant | \(1.38 \times 10^{-16}\) erg/K |

| \(\lambda\) | Wavelength | cm |

| \(T\) | Temperature | K |

\[[B_\lambda] = \frac{[\text{erg·s}][\text{cm/s}]^2}{[\text{cm}]^5} \cdot \frac{1}{[\text{dimensionless}]} = \frac{\text{erg·cm}^2/\text{s}}{\text{cm}^5} = \frac{\text{erg}}{\text{s·cm}^2\text{·sr·cm}}\ \checkmark\]

The units are power per area per solid angle per wavelength interval — exactly what “spectral radiance” should be.

The structure:

- The \(\lambda^{-5}\) factor in front would make short wavelengths dominate…

- But the exponential term \(e^{hc/\lambda k_B T}\) in the denominator suppresses short wavelengths

- The competition between these terms creates the peak

You don’t need to memorize this equation. But you should recognize it and understand its structure. Equations like this will appear throughout your astronomy career. The key skill is knowing how to read them.

- Rayleigh scattering: \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\) (light being redirected by small particles/molecules)

- Rayleigh-Jeans limit: \(B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\) (thermal emission behavior at long wavelength)

Same exponent, different physics.

Limiting Cases: The Key to Taming Complex Equations

The key to not being intimidated by complex equations is understanding their limiting cases — what happens when one term dominates.

Complex equations often have simple limiting behavior. When you encounter a scary equation:

- Identify the variables that can be “large” or “small”

- Take limits to see what terms dominate

- The limiting behavior is usually much simpler

This is a professional skill. Practice it.

Case 1: Long wavelengths (Rayleigh-Jeans limit)

When \(\lambda\) is large (compared to \(hc/k_B T\)), the argument of the exponential is small: \(hc/\lambda k_B T \ll 1\).

For small \(x\), we can approximate \(e^x \approx 1 + x\), so:

\[e^{hc/\lambda k_B T} - 1 \approx \frac{hc}{\lambda k_B T}\]

Substituting into the Planck function:

\[B_\lambda \approx \frac{2hc^2}{\lambda^5} \cdot \frac{\lambda k_B T}{hc} = \frac{2ck_B T}{\lambda^4}\]

This is the Rayleigh-Jeans law — classical physics works at long wavelengths because quantum effects are negligible when \(h\nu \ll k_B T\).

Case 2: Short wavelengths (Wien limit)

When \(\lambda\) is small, \(hc/\lambda k_B T \gg 1\). The exponential dominates, and the “-1” in the denominator becomes negligible:

\[B_\lambda \approx \frac{2hc^2}{\lambda^5} e^{-hc/\lambda k_B T}\]

The exponential cuts off emission at short wavelengths — this is the quantum suppression that prevents the ultraviolet catastrophe. You can’t emit photons whose energy exceeds the thermal energy available.

| Regime | Condition | Behavior | Physical reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long \(\lambda\) | \(hc/\lambda \ll k_B T\) | \(B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\) | Classical physics works; photons are “cheap” |

| Short \(\lambda\) | \(hc/\lambda \gg k_B T\) | \(B_\lambda \to 0\) exponentially | Quantum suppression; photons are “expensive” |

Rayleigh-Jeans limit: \(B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\)

- If temperature doubles (at fixed \(\lambda\)), the intensity ___?

- If wavelength doubles (at fixed \(T\)), the intensity ___?

- You observe two blackbodies at the same temperature, one at \(\lambda = 1\) cm and one at \(\lambda = 0.5\) cm. How do their Rayleigh-Jeans intensities compare?

- Doubles (\(\times 2\)) — intensity is directly proportional to \(T\)

- Decreases by \(2^4 = 16\times\) — the \(\lambda^{-4}\) dependence is steep

- The shorter wavelength is \((1/0.5)^4 = 16\times\) brighter — this is why the “ultraviolet catastrophe” predicted infinite UV emission!

In the Rayleigh-Jeans limit (\(B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\)), does intensity increase or decrease with:

- Temperature?

- Wavelength?

From \(B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\):

Temperature: Intensity increases linearly with \(T\). Hotter = brighter (in this limit).

Wavelength: Intensity decreases as \(\lambda^{-4}\). Shorter wavelengths are brighter (in this limit).

But remember: this limit only applies at long wavelengths where \(hc/\lambda \ll k_B T\). At short wavelengths, the Wien limit takes over and intensity drops exponentially.

Part 5: Wien’s Displacement Law

The Peak Wavelength

The Planck function has a peak — a wavelength where emission is maximum. This peak wavelength depends only on temperature:

\[ \lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1} \tag{4}\]

Wien's displacement law

What it predicts

Given temperature \(T\), it predicts the peak wavelength \(\lambda_{\text{peak}}\) of thermal emission.

What it depends on

\(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\).

What it's saying

Hotter objects peak at shorter wavelengths (bluer); cooler objects peak at longer wavelengths (redder).

Assumptions

- Object radiates as a blackbody (or approximately so)

- Applies to thermal (temperature-driven) radiation

See: the equation

where \(b = 0.2898\ \text{cm·K} = 2.898\times10^{6}\ \text{nm·K}\) is Wien’s displacement constant.

Here “peak wavelength” means the maximum of \(B_\lambda\) (brightness per unit wavelength). If you instead plot brightness per unit frequency (\(B_\nu\)), the peak appears at a different wavelength — same physical spectrum, different binning.

Conversion anchor: \(500\ \text{nm} = 5\times10^{-5}\ \text{cm}\).

This can be rewritten as:

\[\lambda_{\text{peak}} \cdot T = 0.2898\ \text{cm·K} = 2.898\times10^{6}\ \text{nm·K}\]

Let’s unpack Wien’s law:

- What it predicts: The wavelength where a blackbody emits most intensely

- What it depends on: Only temperature — nothing else!

- The story: \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\) — hotter objects peak at shorter (bluer) wavelengths. Cooler objects peak at longer (redder) wavelengths.

- Units check: \([\lambda] = [\text{cm·K}]/[\text{K}] = \text{cm}\) ✓

- Assumptions: Object is a perfect blackbody

This is why color encodes temperature. Hot stars appear blue because their Planck curves peak in the blue/UV. Cool stars appear red because their peaks are in the red/infrared.

Wien’s law: \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1}\), so \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\)

- If temperature doubles, peak wavelength ___?

- If temperature is halved, peak wavelength ___?

- Star A has \(T = 6000\) K; Star B has \(T = 3000\) K. How do their peak wavelengths compare?

- Halves (\(\times \frac{1}{2}\)) — peak wavelength is inversely proportional to temperature

- Doubles (\(\times 2\)) — cooler means longer peak wavelength

- Star B peaks at \(2\times\) the wavelength of Star A. If Star A peaks at 500 nm (green), Star B peaks at 1000 nm (infrared). This is why hot stars are blue and cool stars are red!

Where Does Wien’s Law Come From? (Optional Deep Dive)

Wien’s law comes from finding the maximum of the Planck function — setting \(dB_\lambda/d\lambda = 0\) and solving for \(\lambda\).

This requires calculus (product rule and chain rule applied to the Planck function). The calculation is involved, but the result is elegant:

\[\frac{hc}{\lambda_{\text{peak}} k_B T} \approx 4.965\]

Rearranging gives:

\[\lambda_{\text{peak}} = \frac{hc}{4.965\, k_B T} = \frac{b}{T}\]

where \(b = hc/(4.965\, k_B) = 0.2898\ \text{cm·K}\).

Why this matters: Wien’s law isn’t arbitrary — it follows directly from the physics of the Planck function. This is why calculus matters: it lets you extract simple, powerful results from complex equations.

The OBAFGKM spectral sequence you’ll learn in Module 2 is fundamentally a temperature sequence. O stars (\(T \sim 40{,}000\) K) peak in the far UV; M stars (\(T \sim 3000\) K) peak in the near-infrared. Wien’s law is the physics behind the classification — color is temperature. When we add spectral lines to the picture, we refine this into a complete stellar taxonomy.

Worked Example: The Sun

Problem: The Sun’s spectrum peaks at approximately 500 nm (green-yellow light). What is the Sun’s surface temperature?

Solution:

Using Wien’s law:

\[T = \frac{b}{\lambda_{\text{peak}}}\]

Substituting values:

\[T = \frac{2.898 \times 10^{6}\ \text{nm·K}}{500\ \text{nm}}\]

\[T = 5796\ \text{K} \approx 5800\ \text{K}\]

Interpretation: The Sun’s surface temperature is about 5800 K. We determined this using only the color of sunlight — no thermometer required, no spacecraft needed. This is astronomical inference in action.

\[[T] = \frac{[\text{cm·K}]}{[\text{cm}]} = \text{K}\ \checkmark\]

Worked Example: Comparing Stars

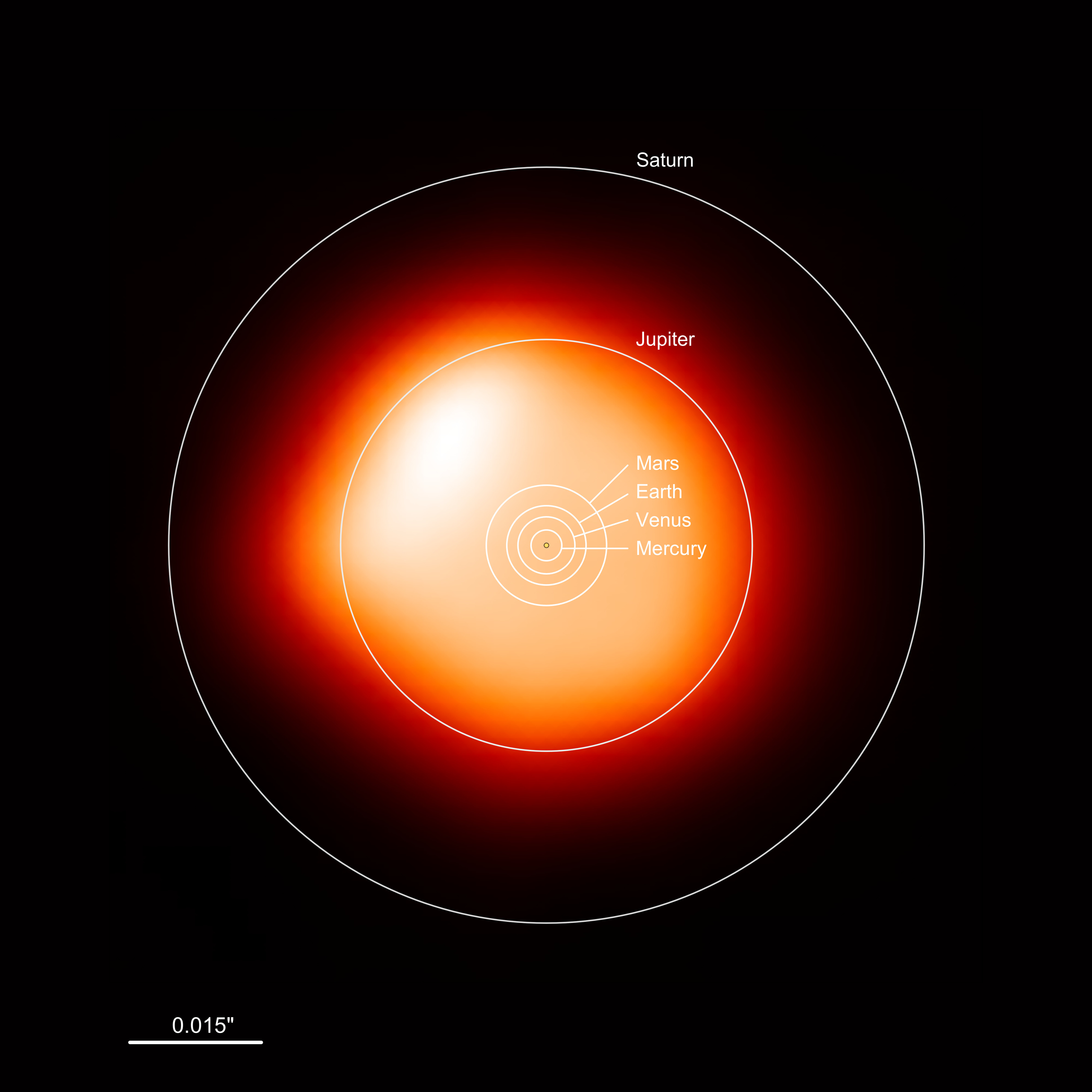

Problem: Betelgeuse (a red supergiant in Orion) has a peak wavelength around 830 nm. Rigel (a blue supergiant, also in Orion) peaks around 240 nm. Calculate their surface temperatures.

Solution:

For Betelgeuse: \[T_{\text{Betelgeuse}} = \frac{2.898 \times 10^{6}\ \text{nm·K}}{830\ \text{nm}} = 3490\ \text{K} \approx 3500\ \text{K}\]

For Rigel: \[T_{\text{Rigel}} = \frac{2.898 \times 10^{6}\ \text{nm·K}}{240\ \text{nm}} = 12075\ \text{K} \approx 12000\ \text{K}\]

What to notice: Betelgeuse is HUGE — it would engulf Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars, and extend to about 4 AU, approaching but not quite reaching Jupiter’s orbit (5.2 AU). Red supergiants are cool (~3,500 K) but luminous because of their enormous surface area. (Credit: ESO/L. Calçada)

Interpretation: Rigel is about 3.5× hotter than Betelgeuse. The color difference — blue vs. red — directly reflects this temperature difference. When you look at the constellation Orion, you’re literally seeing temperature encoded as color: Betelgeuse (the red shoulder) is cool; Rigel (the blue foot) is hot.

- Look up side-by-side images of Betelgeuse and Rigel. Which is hotter, and by roughly what factor?

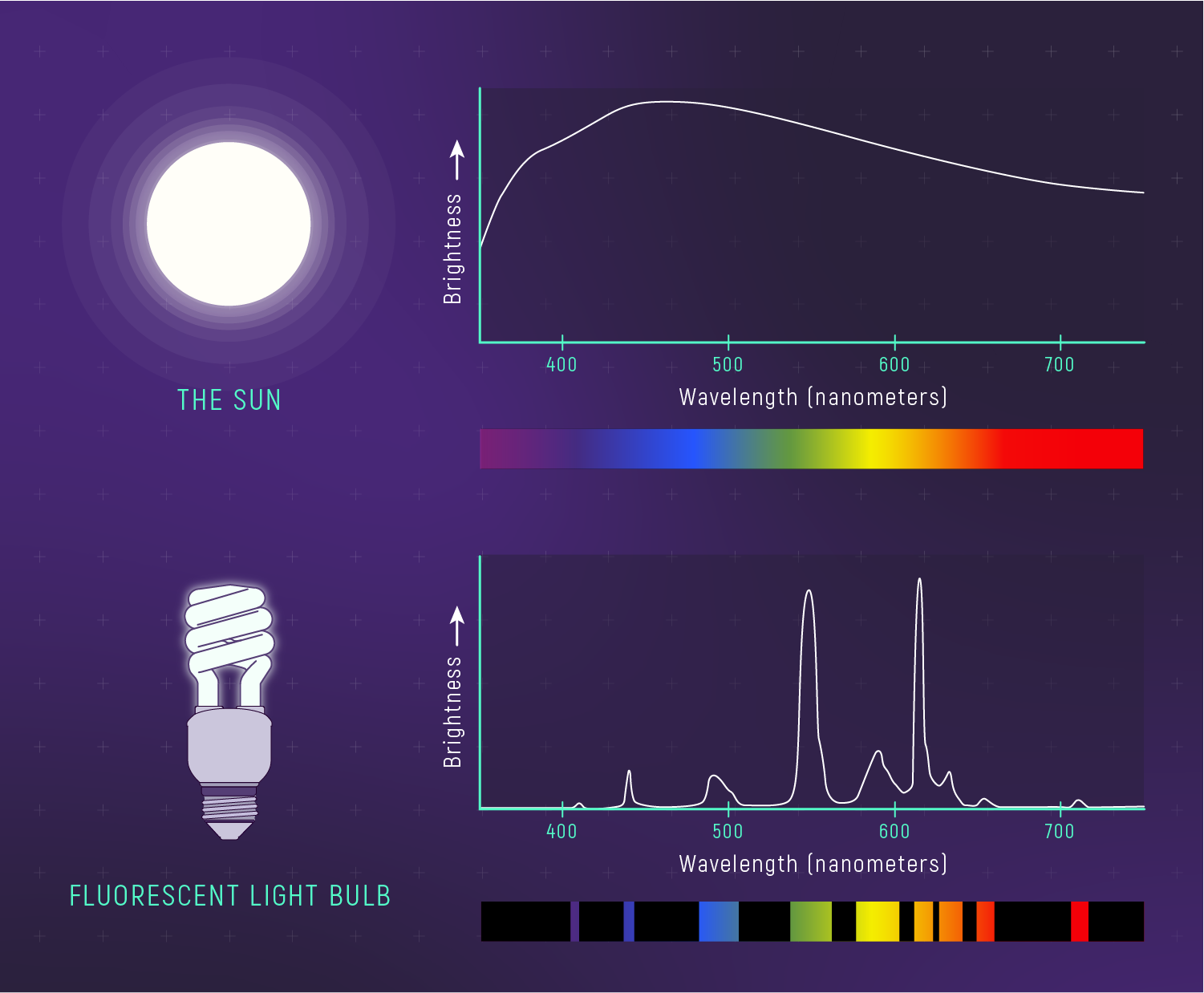

- Compare spectra from an incandescent bulb, an LED bulb, and a fluorescent bulb. Which looks most continuous, and which look line-dominated?

A Common Misconception: Peak ≠ Only

Question: Rigel’s peak wavelength (240 nm) is in the ultraviolet. Why does Rigel appear blue-white to our eyes, not invisible?

Answer: The Planck curve is broad. Rigel emits strongly across a wide range of wavelengths, including the entire visible spectrum. But it emits more blue light than red light (because the visible band is on the blue side of its peak). Our eyes perceive this imbalance as blue-white.

Similarly, Betelgeuse peaks in the near-infrared (830 nm), but it still emits plenty of visible light — just more red than blue. Hence its red color.

The lesson: Peak wavelength ≠ only wavelength. Blackbodies emit at all wavelengths; the peak just tells you where emission is strongest.

The peak depends on how you plot the spectrum. If you plot “per unit wavelength” (\(B_\lambda\)), you get one peak wavelength. If you plot “per unit frequency” (\(B_\nu\)), the peak occurs at a different place. It’s the same physical spectrum — the difference is the binning.

Question: An object has a peak wavelength of 1000 nm. What is its temperature? Is this object hotter or cooler than the Sun?

\[T = \frac{2.898 \times 10^{6}\ \text{nm·K}}{1000\ \text{nm}} = 2898\ \text{K} \approx 2900\ \text{K}\]

This is about half the Sun’s temperature (5800 K), so the object is cooler than the Sun.

An object at 2900 K would glow deep red — think of a hot coal or a very cool star like Proxima Centauri (our nearest stellar neighbor, an M dwarf at ~3000 K).

Worked Example: The Cosmic Microwave Background

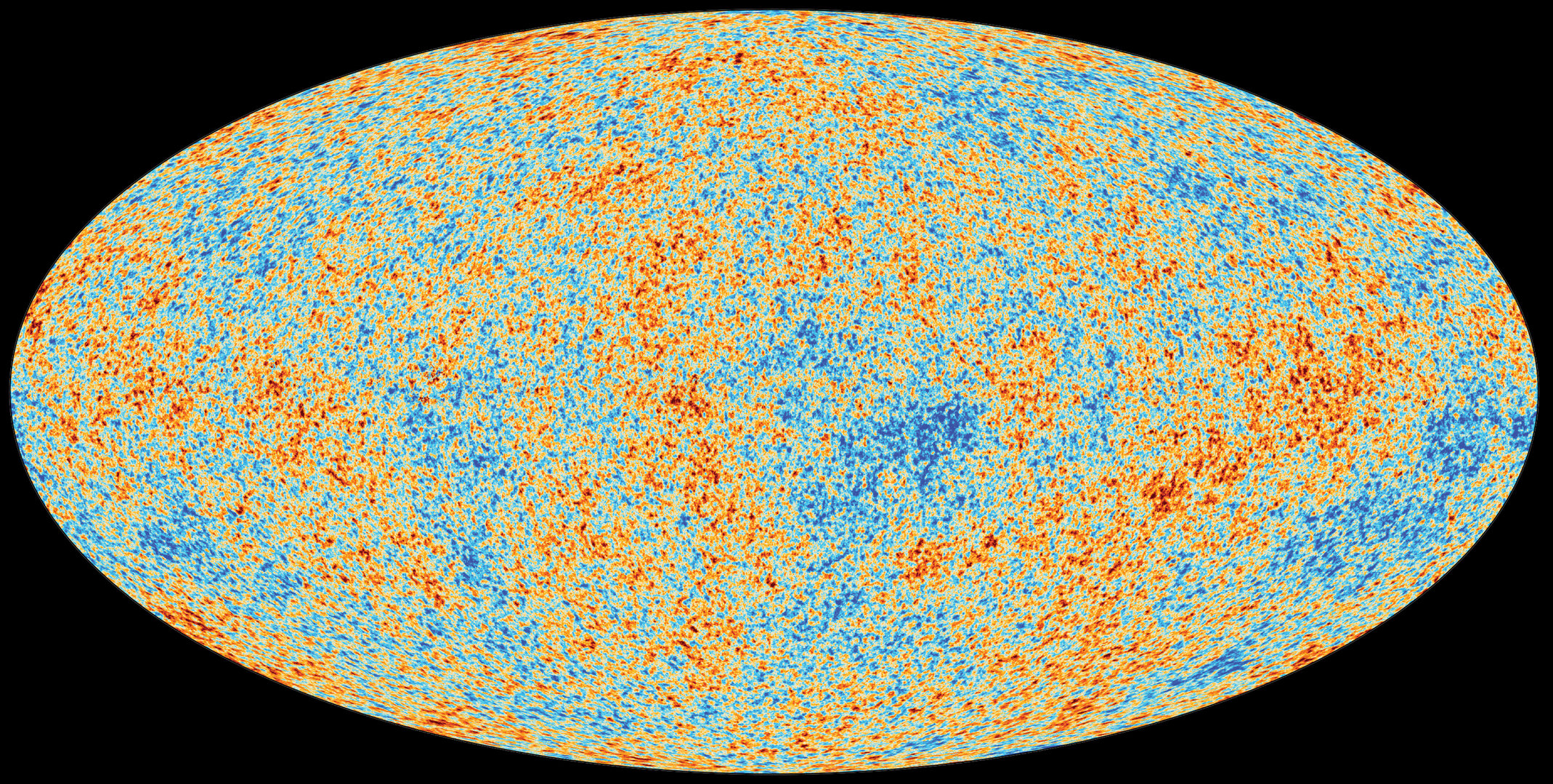

Problem: The Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) — the afterglow of the Big Bang — peaks at a wavelength of about \(0.11\) cm. What is the temperature of the CMB?

Solution:

\[T_{\text{CMB}} = \frac{0.2898\ \text{cm·K}}{0.11\ \text{cm}} = 2.63\ \text{K} \approx 2.7\ \text{K}\]

What to notice: The CMB is the most perfect blackbody ever measured (T = 2.725 K). These color variations show temperature fluctuations of only ±0.0002 K — the seeds of all cosmic structure. (Credit: ESA/Planck Collaboration)

Interpretation: The CMB has a temperature of about 2.7 K — just 2.7 degrees above absolute zero. This is the temperature of the universe itself, left over from the hot early cosmos that has been cooling for 13.8 billion years as space expands.

The CMB is the most perfect blackbody ever measured. NASA’s COBE satellite (1989) confirmed the spectrum matches a Planck curve with deviations \(\lesssim 50\) ppm — a stunning confirmation of Big Bang cosmology. ESA’s Planck satellite (2009–2013) later mapped the tiny temperature fluctuations (±0.0002 K) with unprecedented precision; these variations are the seeds from which all galaxies and large-scale structure grew. We’ll return to the CMB in Module 4 when we study cosmology.

ESA: Cosmic Microwave Background Radiation — Background on the CMB and Planck mission.

Problem: Mars has an average surface temperature of about 210 K. At what wavelength does Mars emit most strongly?

Using Wien’s law: \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1}\)

\[\lambda_{\text{peak}} = \frac{0.2898\ \text{cm·K}}{210\ \text{K}} = 1.4 \times 10^{-3}\ \text{cm} = 14\ \mu\text{m}\]

Mars peaks in the thermal infrared — invisible to human eyes but detectable by infrared telescopes. This is why spacecraft studying Mars carry infrared instruments: they can “see” the planet’s own thermal emission, not just reflected sunlight.

Proportional check: Mars (\(T \approx 210\) K) is about 28× cooler than the Sun (\(T \approx 5800\) K), so its peak wavelength is 28× longer: \(500\ \text{nm} \times 28 \approx 14\ \mu\text{m}\). ✓

Before reading further: You observe a nebula that glows with a bright red color, but only at one specific wavelength (656.3 nm). Meanwhile, a nearby star shows a smooth rainbow with dark lines at specific wavelengths.

- Which object is producing an emission spectrum? Which is producing an absorption spectrum?

- What does this tell you about the physical conditions in each object?

(Hint: Think about what’s needed to produce each spectrum type.)

Part 6: Atoms and Spectral Lines

The Sun’s spectrum isn’t a smooth rainbow — it’s crossed by hundreds of dark lines. Those absorption lines are not imperfections; they are information. Each line is a clue about the atoms the light passed through on its way out of the star.

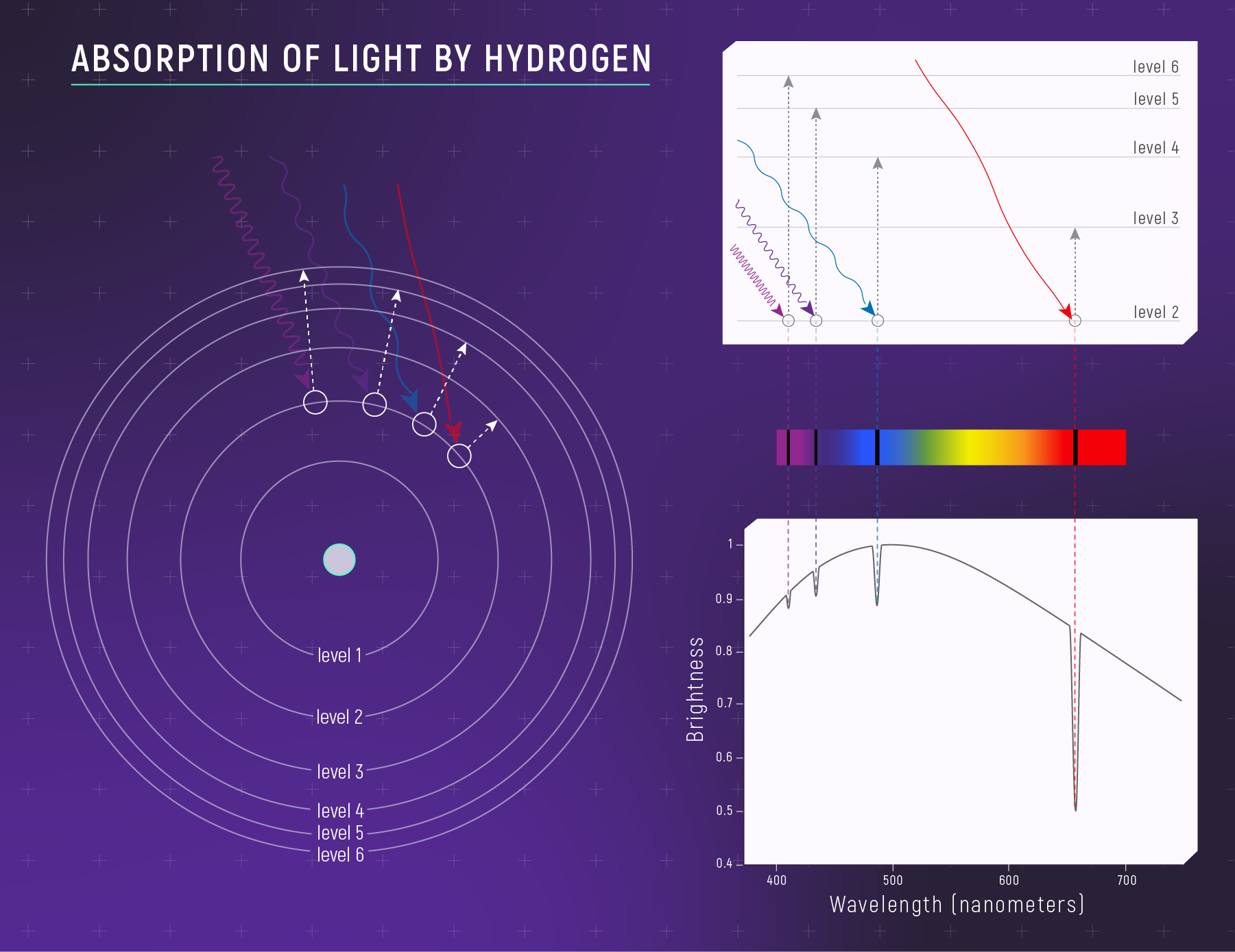

To understand why those lines appear at specific wavelengths, we need one key idea: atoms have quantized energy levels.

The Bohr Model (Hydrogen as a First Example)

Modern quantum mechanics is deeper than the Bohr model, but the Bohr model gets the essential story right — and it gives correct energies for hydrogen.

In this model, the electron in hydrogen can only occupy discrete energy levels labeled by an integer \(n = 1, 2, 3, \dots\).

What to notice: Hydrogen absorbs specific wavelengths because electrons jump UP between quantized energy levels. Each dark line = one electron transition. E = hν determines which wavelengths. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

For hydrogen, the approximate energy of level \(n\) is:

\[ E_n = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{n^2} \tag{5}\]

Hydrogen energy levels (Bohr model)

What it predicts

Given principal quantum number \(n\), it predicts the (approximate) bound-state energy \(E_n\) for hydrogen.

What it depends on

Scales as \(E_n \propto -1/n^2\).

What it's saying

Hydrogen’s electron energies are quantized: only discrete levels are allowed. Higher \(n\) means less tightly bound (energy closer to 0).

Assumptions

- Hydrogen atom (one electron, one proton)

- Bohr model approximation (non-relativistic; ignores fine structure/spin)

- Energies are commonly reported in eV (conversion: \(1\ \text{eV} \approx 1.6\times10^{-12}\ \text{erg}\))

See: the equation

The ground state (\(n=1\)) is the most tightly bound. Higher \(n\) levels have energies closer to zero, meaning the electron is less tightly bound and easier to ionize.

The hydrogen ionization energy is 13.6 eV. Converting to a photon wavelength with \(E = hc/\lambda\) gives \(\lambda \approx 9.1\times10^{-6}\ \text{cm} \approx 91\ \text{nm}\) — the Lyman limit, in the ultraviolet. This is one reason UV astronomy requires the atmosphere to be “out of the way.”

Photon Absorption and Emission

When an electron changes energy levels, the atom must absorb or emit a photon whose energy matches the energy difference:

\[\Delta E = E_{\text{upper}} - E_{\text{lower}} = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda}\]

\[ E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1} \tag{6}\]

Photon energy (Planck relation)

What it predicts

Given wavelength \(\lambda\) (or frequency \(\nu\)), it predicts the energy \(E\) of a single photon.

What it depends on

\(E \propto \nu\) and \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\).

What it's saying

Shorter wavelength = higher energy photon. The constant \(h\) signals quantum mechanics is at work.

Assumptions

- Light comes in discrete packets (photons)

- Each photon carries energy proportional to its frequency

- This is a quantum mechanical result—classical physics cannot predict it

See: the equation

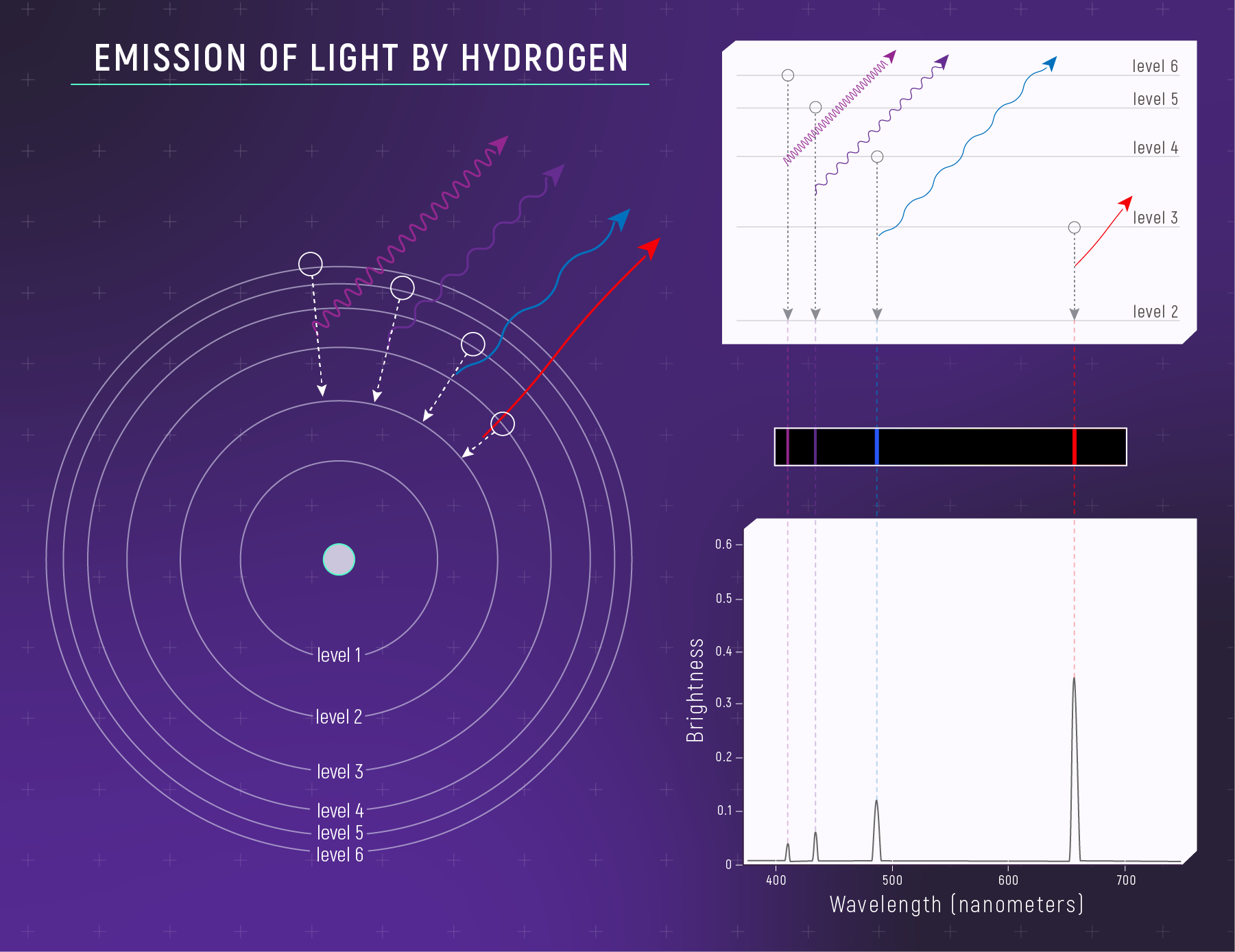

An absorption line happens when photons of a particular energy are removed from a beam because electrons jump up to higher levels. An emission line happens when a thin gas produces photons at specific energies because electrons fall down to lower levels.

What to notice: Hydrogen emits specific wavelengths because electrons fall DOWN between energy levels. Each bright line = one electron transition. The Balmer series (visible) comes from transitions to level 2. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

Kirchhoff’s Laws: Three Types of Spectra

Kirchhoff recognized that there are three basic spectrum “shapes,” and each corresponds to a different physical situation:

This is how we know what stars are made of without sampling them.

What to notice: Three spectrum types encode different physics. Continuous = hot dense source. Absorption = cool gas in front of hot source. Emission = hot thin gas. Same atoms, different conditions, different spectra. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

- Continuous spectrum: hot, dense matter (a blackbody-like source).

- Absorption spectrum: cool gas in front of a hot continuous source.

- Emission spectrum: hot, thin gas with no bright background.

The remarkable thing is that the same atoms are involved in both absorption and emission — what changes is the density/temperature structure and whether there is a bright continuum behind the gas.

Kirchhoff’s laws reveal that the same atoms can produce absorption or emission depending on the viewing geometry and physical conditions. A nebula viewed against empty space shows emission lines; the same gas viewed against a background star shows absorption. In stellar atmospheres, we see absorption lines because the cooler outer layers lie in front of the hotter interior. Understanding where light originates and what it passes through is essential for interpreting any astronomical spectrum.

What Spectral Lines Can Tell You

Spectral lines let us infer far more than composition. In Module 2 we’ll build on this to read additional information from spectra:

- Composition: which elements are present (each has a unique pattern of lines)

- Temperature: which transitions are populated (line strengths and ratios)

- Velocity: Doppler shifts (lines move slightly blueward/redward)

- Density/pressure: line widths and which lines can form

Quick Checks: Atoms and Spectra

Question: Why do absorption lines occur at specific wavelengths instead of at all wavelengths?

Answer: Because electrons in atoms can only change energy by specific allowed amounts. A photon can only be absorbed if its energy matches one of those allowed energy differences.

Question: You observe a nebula that glows strongly red. Which spectrum type is this likely to be?

Answer: An emission spectrum from hot, thin gas. A common red emission line in many nebulae is hydrogen’s H\(\alpha\) (a Balmer-series transition).

Question: In an absorption spectrum, where must the absorbing gas be located relative to the bright source?

Answer: The absorbing gas must be in front of the bright continuous source (along the line of sight), so it can remove specific wavelengths from the light that reaches you.

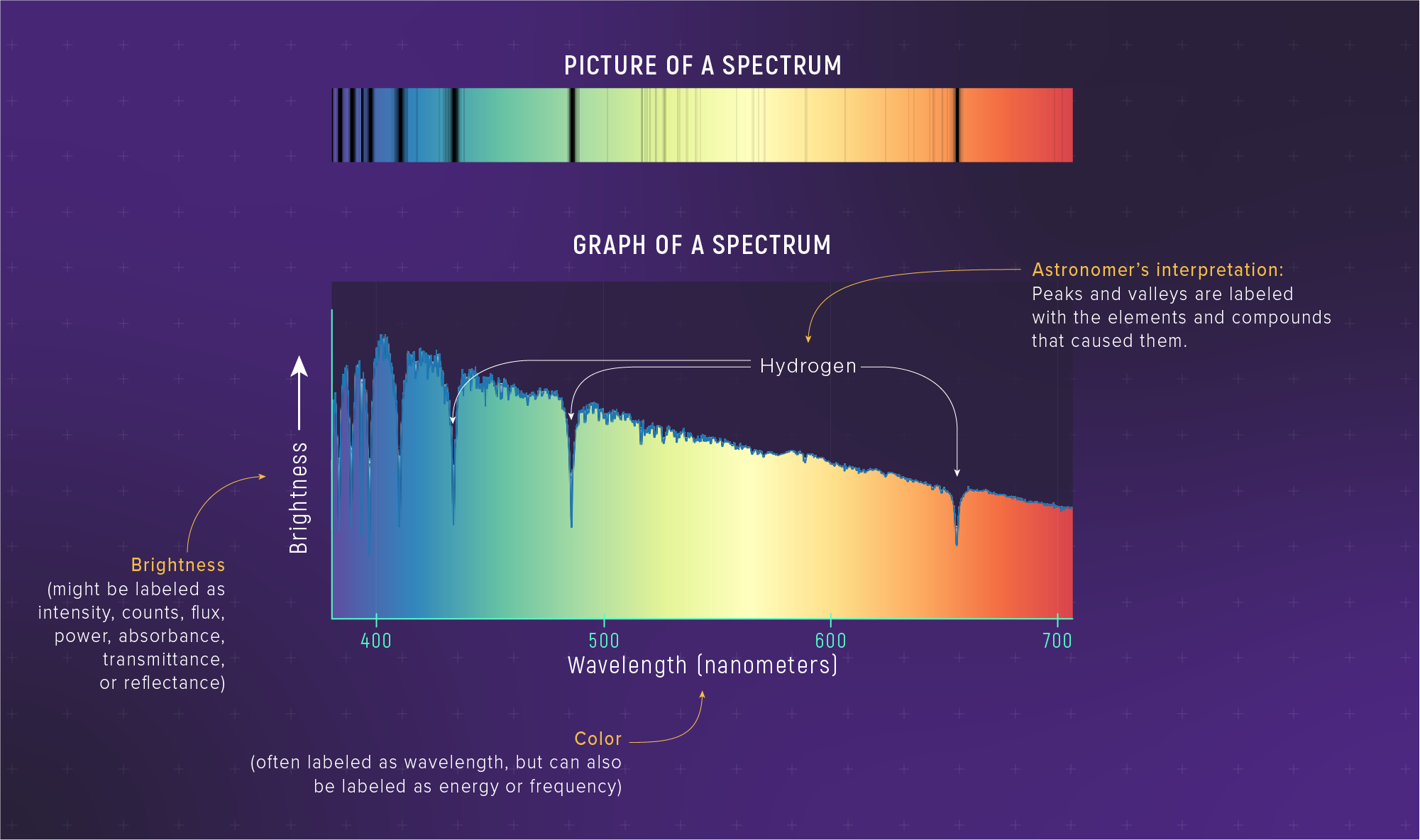

Part 7: Real Stellar Spectra

Beyond the Ideal Blackbody

Stars are approximately blackbodies, but not perfectly. Real stellar spectra show two features:

- The overall shape follows a Planck curve (giving us temperature via Wien’s law)

- Absorption lines appear as dark notches at specific wavelengths (giving us composition via spectroscopy)

What to notice: A real stellar spectrum combines continuous (blackbody) shape with absorption lines. The overall curve gives temperature (Wien); the lines give composition (spectroscopy). Two inference tools in one observation. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

The figure shows the spectrum of Altair, a nearby A-type star. The smooth curve is the blackbody shape; the sharp dips are absorption lines from hydrogen and other elements in the star’s atmosphere.

Two inference tools in one observation:

- The curve shape → temperature (Wien’s law)

- The line positions → composition (spectroscopy)

What to notice: The Sun’s spectrum is nearly a smooth blackbody curve (continuous). A fluorescent bulb shows discrete spikes—it’s NOT a thermal emitter. Spectrum shape tells you about the emission mechanism. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

Notice the difference between the Sun’s spectrum (approximately continuous, like a blackbody) and a fluorescent bulb (discrete emission lines). The spectrum shape tells you about the emission mechanism — thermal vs. non-thermal.

Doppler Shift: Motion in Spectral Lines

Spectral lines are not just composition fingerprints — they are speedometers. If a source moves toward or away from us, its spectral lines shift slightly. That shift encodes the line‑of‑sight velocity, which means we can measure motion using nothing but light.

What to notice: Motion toward us compresses wavelengths (blueshift); motion away stretches them (redshift). This lets us measure stellar velocities—and detect exoplanets via the star’s wobble. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

For speeds much smaller than the speed of light, the non‑relativistic Doppler shift is:

\[ \frac{\Delta \lambda}{\lambda_0} = \frac{v_r}{c} \tag{7}\]

Doppler shift (non-relativistic)

What it predicts

Given rest wavelength \(\lambda_0\) and observed wavelength \(\lambda_{\text{obs}}\), it predicts the radial velocity \(v_r\) (or vice versa).

What it depends on

The fractional shift scales as \(\Delta\lambda/\lambda_0 \propto v_r\) and inversely with \(c\).

What it's saying

Motion along the line of sight stretches or compresses wavelengths: away → redshift, toward → blueshift.

Assumptions

- Speeds are much less than the speed of light (non-relativistic)

- Only the line-of-sight component matters

- Rest wavelength is known from lab measurements

See: the equation

Here \(\Delta\lambda = \lambda_{\text{obs}} - \lambda_0\), \(\lambda_0\) is the rest wavelength measured in the lab, and \(v_r\) is the radial (line‑of‑sight) velocity. If \(v_r > 0\) the lines shift to longer wavelengths (redshift); if \(v_r < 0\) they shift to shorter wavelengths (blueshift).

This non-relativistic form is accurate when \(|v_r| \ll c\) (for example, stars and planets moving at km/s to hundreds of km/s). For very large redshifts in cosmology, we need relativistic/cosmological treatments.

Why it matters: this tiny shift lets us infer some of the biggest stories in astronomy:

- Exoplanets: a star’s tiny wobble reveals an orbiting planet.

- Binary stars: Doppler shifts give orbital speeds and masses.

- Galaxy rotation curves: line shifts map rotation and point to dark matter.

- Cosmic expansion: redshift shows the universe is expanding.

We will revisit Doppler shifts in greater depth in Module 2, where we use them to measure stellar masses and detect exoplanets.

Doppler shifts connect directly to Lecture 3 (gravity and orbits). For a binary star, the observed velocity amplitude plus the orbital period gives you the orbit size via Kepler’s laws. Combined with Newton’s version of Kepler’s third law (\(P^2 \propto a^3/M\)), you can solve for stellar masses — the most fundamental property of a star. Light (Doppler) + gravity (Kepler) together unlock what we cannot measure directly.

Question: A spectral line is observed at a slightly longer wavelength than its lab value. Is the source moving toward us or away from us?

Answer: Away from us (redshift).

Before reading further: The James Webb Space Telescope has a 6.5-meter mirror, while the Hubble Space Telescope has a 2.4-meter mirror.

- How much more light-gathering power does JWST have compared to Hubble?

- Which telescope can see finer detail at the same wavelength?

(Hint: Think about how area and resolution scale with diameter.)

Part 8: Telescopes as Light Buckets

Astronomical objects are far away and often faint. Telescopes extend our reach in two distinct ways: they collect more photons and they can resolve finer detail.

Collecting Area: Why Bigger Is Better

The simplest telescope question is: how much light do you collect? For a circular aperture, the collecting area is

\[ A = \pi\left(\frac{D}{2}\right)^2 \tag{8}\]

Telescope collecting area

What it predicts

How much light a telescope can gather via its geometric collecting area \(A\).

What it depends on

Scales as \(A \propto D^2\) for a circular aperture.

What it's saying

Doubling diameter gives 4× collecting area, which improves photon counts and signal-to-noise for faint objects.

Assumptions

- Circular aperture; ignores central obstruction and throughput losses

See: the equation

What to notice: Collecting area scales as diameter squared. A telescope twice as wide collects four times as much light. (Credit: Illustration: A. Rosen (SVG))

Collecting area: \(A = \pi (D/2)^2 \propto D^2\)

- If diameter doubles, collecting area ___?

- If diameter triples, collecting area ___?

- JWST (\(D = 6.5\) m) vs. Hubble (\(D = 2.4\) m): how do their collecting areas compare?

- Quadruples (\(\times 4\)) — area scales as \(D^2\)

- Increases by \(3^2 = 9\times\) — same \(D^2\) scaling

- JWST has \((6.5/2.4)^2 \approx 7.3\times\) more collecting area than Hubble — it can see much fainter objects in the same exposure time

Angular Resolution: Why Bigger Is Sharper

Even if you collect lots of light, you can’t see detail smaller than your telescope’s angular resolution. Diffraction sets a fundamental limit:

\[ \theta_{\min} \approx \frac{\lambda}{D} \tag{9}\]

Diffraction-limited angular resolution

What it predicts

The smallest angular separation \(\theta_{\min}\) a telescope can resolve (diffraction limit).

What it depends on

Depends on wavelength \(\lambda\) and aperture diameter \(D\); scales as \(\theta_{\min} \propto \lambda/D\).

What it's saying

Bigger apertures resolve finer detail; shorter wavelengths resolve finer detail. Use radians when \(\lambda\) and \(D\) use the same length units.

Assumptions

- Diffraction-limited optics (no atmospheric seeing)

- Order-of-magnitude form for a circular aperture

See: the equation

What to notice: Angular resolution improves with larger diameter. The diffraction limit θ ≈ λ/D sets the finest detail a telescope can distinguish. (Credit: Illustration: A. Rosen (SVG))

For a circular aperture, a more precise form is \(\theta \approx 1.22\,\lambda/D\). In this course we usually use \(\lambda/D\) when doing scaling arguments.

Angular resolution: \(\theta \approx \lambda D^{-1}\), so \(\theta \propto \lambda D^{-1}\)

- If diameter doubles (at fixed \(\lambda\)), resolution ___?

- If wavelength doubles (at fixed \(D\)), resolution ___?

- You observe at \(\lambda = 2\ \mu\)m instead of \(\lambda = 0.5\ \mu\)m with the same telescope. How does resolution change?

- Improves by \(2\times\) (angle halves) — bigger mirrors resolve finer detail

- Worsens by \(2\times\) (angle doubles) — longer wavelengths give blurrier images

- Resolution worsens by \(4\times\) — you can resolve \(4\times\) less detail in the infrared than visible. This is why infrared astronomy often needs larger mirrors!

The Atmosphere Limit (and How We Beat It)

Ground-based optical telescopes often fail to reach the diffraction limit because atmospheric turbulence blurs images (this is called seeing). Adaptive optics can correct some of that blur in real time, and space telescopes avoid the atmosphere entirely.

Mirrors vs. Lenses (Brief)

Large modern telescopes are reflectors, not refractors. Mirrors can be supported from behind (and even segmented), making very large apertures practical. Lenses must be supported at the edges and suffer from chromatic aberration, so extremely large refracting telescopes are not feasible.

The resolution relation \(\theta \propto \lambda/D\) explains why radio astronomers need dishes tens to hundreds of meters across. At \(\lambda = 21\) cm (the hydrogen line), a 10-meter dish has resolution \(\theta \sim 21/1000 \sim 0.02\) rad \(\sim 1°\) — worse than your naked eye! To match Hubble’s 0.05″ resolution at radio wavelengths requires continent-scale interferometry (the VLBA, Event Horizon Telescope). The physics of diffraction forces the engineering.

Quick Checks: Telescopes

Question: A telescope with a 400 cm mirror is replaced by one with an 800 cm mirror. By what factor does the collecting area increase?

Answer: Collecting area scales as \(D^2\), so the ratio is \((800/400)^2 = 4\). The new telescope collects 4× as many photons.

Question: The Hubble Space Telescope has \(D = 240\) cm and observes at \(\lambda = 500\ \text{nm}\). Estimate its diffraction-limited angular resolution.

Answer: Convert to cgs lengths: \(\lambda = 500\ \text{nm} = 5.0\times10^{-5}\ \text{cm}\).

\(\theta \approx \lambda/D \approx (5.0\times10^{-5}\ \text{cm})/(240\ \text{cm}) \approx 2.1\times10^{-7}\ \text{rad}\).

Converting using \(206{,}265\) arcsec per rad gives \(\theta \approx 0.04\) arcsec (order of magnitude). For a circular aperture, a common Rayleigh-criterion form is \(\theta \approx 1.22\,\lambda/D\), which gives a similar scale.

Question: Why can’t we build a 5000 cm optical telescope using a single glass lens?

Answer: A lens that large would be extremely heavy and must be supported only at its edge, so it would sag and distort. Large mirrors can be supported from behind and can be made thin or segmented, so large reflectors are practical while large refractors are not.

Part 9: Synthesis — The Observable → Model → Inference Chain

Putting It Together

We’ve followed the photon’s story from start to finish: how it’s produced, how it interacts, what it tells us, and how we catch it.

| We measure | We use | We infer |

|---|---|---|

| Peak wavelength (color) | Wien’s law: \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1}\) | Surface temperature |

| Spectrum shape | Planck function | Thermal emission mechanism |

| Scattering behavior | Rayleigh: \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\) | When/why reddening matters |

| Line pattern and type | Kirchhoff’s laws + atomic transitions | Composition and physical conditions |

| Aperture diameter | \(A \propto D^2\), \(\theta \propto \lambda D^{-1}\) | Faintness reach and sharpness |

Preview: What’s Coming

Week 4 (Distance): We’ll learn to measure distance — using parallax, standard candles, and the inverse-square relation. Once we know distance and apparent brightness, we can infer luminosity (intrinsic power output).

Week 5 and beyond (Stars as inference problems): We’ll return to blackbody physics to connect temperature, luminosity, and radius (Stefan–Boltzmann), and we’ll deepen spectroscopy: what line strengths and line shifts reveal about a star’s atmosphere and motion.

Each week, the inference chain grows longer. By the end of Module 2, you’ll be able to characterize a star — temperature, luminosity, radius, and eventually mass — all from the light it sends us.

Proportional Reasoning Practice

The equations in this reading all involve proportional relationships. Mastering these relationships — without reaching for a calculator — is a crucial skill in physics and astronomy. Here’s a summary of the key scalings you should internalize:

| Equation | Key Scaling | In Words |

|---|---|---|

| Wave relation | \(\nu \propto \lambda^{-1}\) | Frequency and wavelength are inversely related |

| Photon energy | \(E \propto \nu\) (or \(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\)) | Higher frequency = higher energy; shorter wavelength = higher energy |

| Rayleigh scattering | \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\) (or \(\sigma \propto \nu^{4}\)) | Scattering is very sensitive to wavelength/frequency |

| Wien’s law | \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\) (or \(\nu_{\text{peak}} \propto T\)) | Hotter objects peak at shorter \(\lambda\) / higher \(\nu\) |

| Rayleigh-Jeans limit | \(B_\lambda \propto T\lambda^{-4}\) | Classical limit: linear in \(T\), steep in \(\lambda\) |

| Collecting area | \(A \propto D^2\) | Area scales as diameter squared |

| Angular resolution | \(\theta \propto \lambda D^{-1}\) | At fixed \(D\): \(\theta \propto \lambda\); at fixed \(\lambda\): \(\theta \propto D^{-1}\) |

Problem: You’re comparing two telescopes observing the same star:

- Telescope A: \(D = 4\) m, observing at \(\lambda = 500\) nm (visible)

- Telescope B: \(D = 8\) m, observing at \(\lambda = 2000\) nm (infrared)

- Which telescope collects more light, and by what factor?

- Which telescope has better angular resolution?

- If both see the same blackbody star at \(T = 5000\) K, which is observing closer to the star’s peak emission?

Telescope B collects \(4\times\) more light. Collecting area scales as \(D^2\): \((8/4)^2 = 4\).

Telescope A has better resolution. Resolution scales as \(\theta \propto \lambda D^{-1}\):

- Telescope A: \(\theta_A \propto 500/4 = 125\) (arbitrary units)

- Telescope B: \(\theta_B \propto 2000/8 = 250\) (arbitrary units)

Smaller \(\theta\) means finer resolution. The infrared telescope’s larger mirror (\(2\times\)) doesn’t compensate for the longer wavelength (\(4\times\)), so Telescope A resolves \(2\times\) finer detail.

Telescope A is closer to the peak. Using Wien’s law with \(T = 5000\) K: \[\lambda_{\text{peak}} = \frac{2.898 \times 10^6\ \text{nm·K}}{5000\ \text{K}} = 580\ \text{nm}\]

Telescope A (500 nm) is close to the peak; Telescope B (2000 nm) is on the red tail of the Planck curve.

The lesson: Proportional reasoning lets you compare options quickly. Larger diameter helps with both light collection (\(D^2\)) and resolution (\(D^{-1}\) in the denominator), but longer wavelengths hurt resolution (\(\lambda\) in the numerator). Real telescope design involves these trade-offs!

Quick Practice

Answer these without a calculator. Then check your reasoning.

- If wavelength decreases by a factor of 3, what happens to frequency?

- Two photons have wavelengths 500 nm and 1000 nm. Which has higher energy, and by what factor?

- Rayleigh scattering scales as \(\lambda^{-4}\). Compare scattering at 400 nm and 800 nm.

- If a blackbody’s peak wavelength is cut in half, what happens to its temperature?

- Frequency increases by a factor of 3.

- The 500 nm photon has 2× higher energy (energy \(\propto \lambda^{-1}\)).

- Scattering at 400 nm is 16× stronger: \((800/400)^4 = 2^4 = 16\).

- Temperature doubles (Wien’s law: \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\)).

Practice Problems

Conceptual

- Kirchhoff’s laws in action. You see three spectra from three different sources:

- A smooth rainbow with dark lines

- A smooth rainbow with no lines

- A dark background with bright lines

- Blackbody or not? You observe two sources. Source A has a smooth spectrum with a single broad peak. Source B has sharp spikes at specific wavelengths (discrete line emission). Which source is better described as a blackbody? What does the non‑blackbody spectrum imply, and what emission mechanism is suggested (thermal continuum vs. atomic transitions)?

- Why skies are red at sunset. Use Rayleigh scattering to explain why the sky is blue in daytime and why the Sun looks red near the horizon. Distinguish what you see when looking away from the Sun (scattered skylight) versus at the Sun near the horizon (transmitted beam after blue light is removed). What changes about the atmospheric path length, and how does \(\lambda^{-4}\) make the effect strong?

- Two telescope goals. If your goal is to (i) detect the faintest possible objects and (ii) resolve the smallest angular details, which telescope property matters most for each? Assume identical throughput and exposure time for faintness, and assume diffraction-limited conditions (space or perfect adaptive optics) for resolution. Justify using the \(D^2\) and \(\lambda/D\) scalings.

- Peak is not only. A star peaks at 250 nm. In 2–4 sentences, explain why it can still appear blue-white to human eyes.

Calculation

- Wave relation. A radio wave has \(\lambda = 3\) cm.

- What is its frequency \(\nu\)?

- Visible light has \(\lambda = 500\) nm. How many times larger is \(\nu_{\text{vis}}\) than \(\nu_{\text{radio}}\)?

- Photon energy from wavelength. A green photon has \(\lambda = 600\) nm.

- Convert this wavelength to cm.

- Compute its frequency.

- Compute its energy in erg using \(E = hc/\lambda\) with \(h = 6.626 \times 10^{-27}\) erg·s and \(c = 2.998 \times 10^{10}\) cm/s.

- Wien’s law temperature. A star’s spectrum peaks at \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = 700\) nm. Use \(b = 2.898 \times 10^6\) nm·K to estimate the temperature. Then compare to the Sun (\(\sim 5800\) K): hotter or cooler, and by roughly what factor?

- Rayleigh scattering ratio. Compute \(\sigma_{450}/\sigma_{900}\) using \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\). Which wavelength is scattered more, and by what factor?

- Telescope scaling. Compare two telescopes observing at the same wavelength:

- Telescope A: \(D = 2\) m

- Telescope B: \(D = 8\) m

- Compute \(A_B/A_A\).

- Compute \(\theta_B/\theta_A\) (diffraction-limited).

- State which telescope is better for faint objects and which gives sharper images.

- Doppler sign and speed. The H\(\alpha\) line (\(\lambda_0 = 656.3\) nm) is observed at 656.6 nm. Is the source approaching or receding? Estimate \(v_r\) using the non-relativistic Doppler relation.

- JWST versus Hubble.

- Compute the collecting-area ratio using \(A \propto D^2\) with \(D_{\text{JWST}} = 6.5\) m and \(D_{\text{HST}} = 2.4\) m.

- Compute the angular-resolution ratio at the same wavelength using \(\theta \propto \lambda D^{-1}\).

- Interpret each ratio in one sentence.

Synthesis

- Temperature plus absorption. A star’s spectrum peaks near 1.0 μm and shows deep absorption lines.

- Use Wien’s law to estimate the temperature.

- Explain what deep absorption lines imply about the atmosphere and viewing geometry using Kirchhoff’s laws.

- What additional information do line positions provide?

- Short-wavelength suppression. Use the Planck function \[B_\lambda(T) = \frac{2hc^2}{\lambda^5}\frac{1}{e^{hc/\lambda k_B T}-1}\] to explain why intensity is suppressed at very short wavelengths.

Scaffolding prompts: - (a) In the short-wavelength limit (\(\lambda \to 0\)), what happens to the prefactor \(\lambda^{-5}\)? - (b) In that same limit, what happens to the exponent \(x = hc/(\lambda k_B T)\) and therefore to \(e^x - 1\)? - (c) Which effect dominates the product, and why does that prevent the ultraviolet catastrophe? - (d) Connect your conclusion to the statement “photons are expensive when \(h\nu \gg k_B T\).”

Reference Tables

Key Equations

| Quantity | Equation | What It Tells You |

|---|---|---|

| Wave relation | \(c = \lambda \nu\) | Wavelength and frequency are inversely related (\(\nu \propto \lambda^{-1}\)) |

| Photon energy | \(E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1}\) | Short wavelength = high energy (\(E \propto \lambda^{-1}\)) |

| Rayleigh scattering | \(\sigma \propto \lambda^{-4}\) | Short wavelengths scatter much more strongly |

| Wien’s law | \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = b T^{-1}\) | Peak wavelength encodes temperature (\(\lambda_{\text{peak}} \propto T^{-1}\)) |

| Bohr levels (H) | \(E_n = -13.6\ \text{eV}\, n^{-2}\) | Atomic energies are quantized (line energies are differences) |

| Collecting area | \(A = \pi(D/2)^2\) | Light-gathering power scales as \(D^2\) |

| Diffraction limit | \(\theta \approx \lambda D^{-1}\) | Angular resolution improves with larger \(D\) and smaller \(\lambda\) |

| Wien’s constant | \(b = 0.2898\) cm·K | Memorize this (or know where to find it) |

Physical Constants

| Constant | Symbol | Value | What It Means |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed of light | \(c\) | \(2.998 \times 10^{10}\) cm/s | Universal speed limit |

| Planck’s constant | \(h\) | \(6.626 \times 10^{-27}\) erg·s | Quantum of action |

| Boltzmann’s constant | \(k_B\) | \(1.38 \times 10^{-16}\) erg/K | Energy per degree of temperature |

| Wien’s constant | \(b\) | \(0.2898\) cm·K | Peak wavelength × temperature |

Temperature and Color

| Object | Temperature | Peak Wavelength | Spectral Band |

|---|---|---|---|

| CMB | 2.7 K | \(0.11\) cm | Microwave |

| Cool dust | 30 K | \(10^{-2}\) cm | Far-IR |

| Brown dwarf | 1000 K | \(2.9\times10^{-4}\) cm | Near-IR |

| M dwarf (Proxima Cen) | 3000 K | \(970\) nm | Near-IR |

| K dwarf | 4500 K | \(640\) nm | Visible (orange) |

| Sun (G dwarf) | 5800 K | \(500\) nm | Visible (green-yellow) |

| A star (Sirius) | 10000 K | \(290\) nm | Near-UV |

| O star | 40000 K | \(72\) nm | Far-UV |

Question 1: Why does the blue star (8000 K) appear blue even though it peaks in the UV?

Answer: The Planck curve is broad, not a spike. Even though the peak is in the UV, the star emits plenty of visible light. But it emits more blue visible light than red visible light (since blue is closer to the UV peak). Our eyes integrate this imbalance and perceive blue.

Question 2: Why does the red star (3000 K) appear red even though it peaks in the infrared?

Answer: Same reason in reverse. The star emits across a broad range including visible light, but more red than blue (since red is closer to the IR peak). We see the imbalance as red.

The key insight: Blackbodies emit at all wavelengths. The peak tells you where emission is strongest, but plenty of light comes out at other wavelengths too. Color perception depends on the ratio of blue to red light, not just the peak location.