Lecture 3: Spectra & Composition

What’s it made of, and how is it moving?

Learning Objectives

After completing this reading, you should be able to:

- Explain Kirchhoff’s three laws and predict whether a source produces a continuous, emission, or absorption spectrum

- Interpret the Bohr model to explain why spectral lines occur at characteristic wavelengths

- Use spectral line wavelengths to determine which elements are present in a star’s atmosphere

- Classify stars by spectral type (OBAFGKM) and explain why this sequence is a temperature sequence, not a composition sequence

- Apply the Doppler shift formula quantitatively to find radial velocities from line shifts

- Distinguish spectral type (temperature) from luminosity class (surface gravity) from metallicity (heavy-element abundance)

- Synthesize multiple spectroscopic clues — line positions, line strengths, line widths, line shifts — to infer stellar properties

- Connect spectral absorption to the greenhouse effect and explain why CO\(_2\) warms Earth

Concept Throughline

Atoms are nature’s barcode readers — each element absorbs and emits light at a unique set of wavelengths determined by its electron energy levels. By measuring where spectral lines appear and how they shift, we read a star’s composition and velocity from across the galaxy. And the same physics that decodes starlight explains why adding CO\(_2\) to an atmosphere warms a planet.

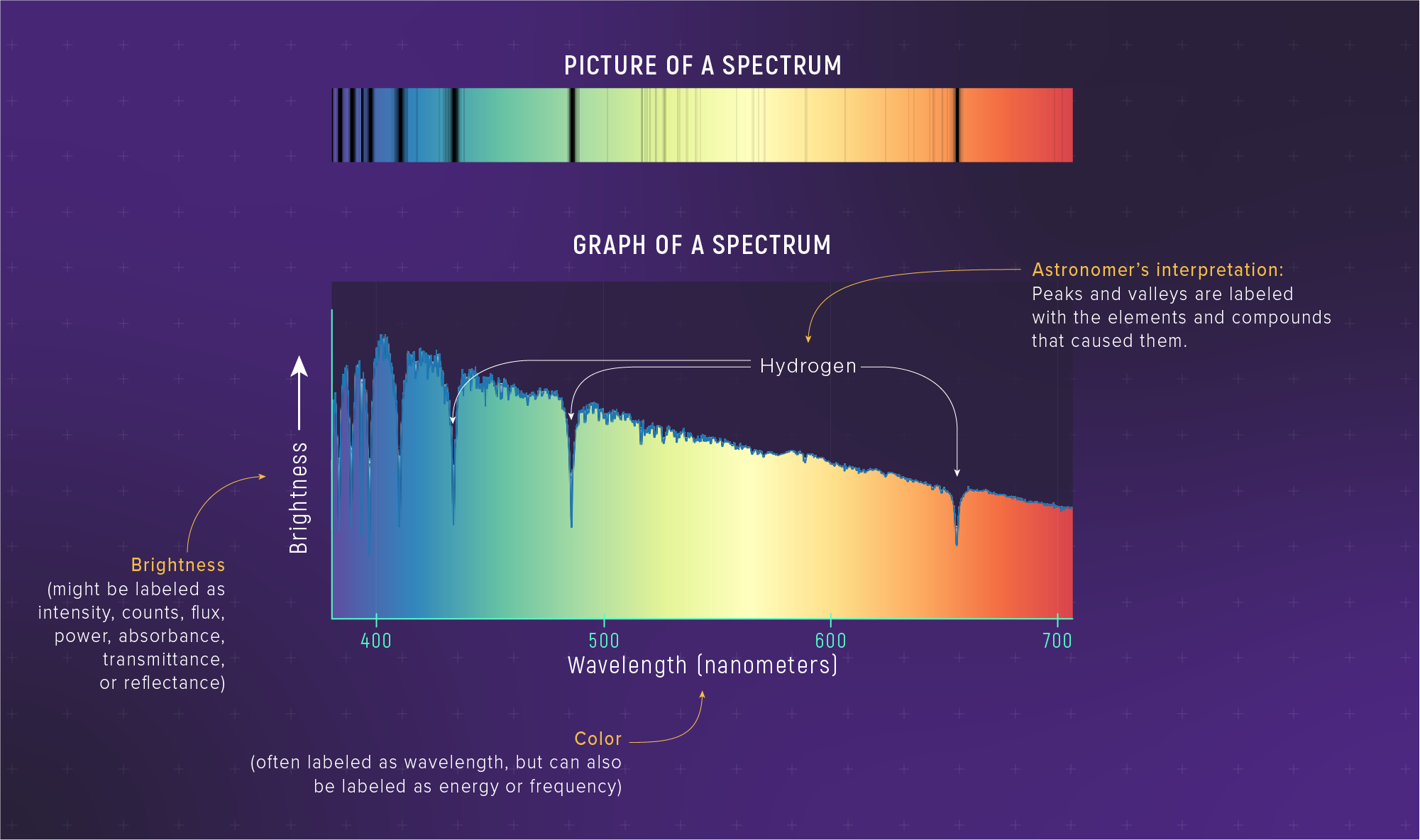

In everyday language, “spectrum” might mean a range or continuum. In astrophysics, a spectrum is the intensity of light as a function of wavelength — a precise, quantitative measurement obtained by dispersing light through a prism or diffraction grating. A spectrum is data, not decoration. Every absorption line, every emission peak, every slope of the continuum encodes physics. When we say “take a spectrum,” we mean “measure the brightness at every wavelength.”

Track A (Core, ~25 min): Read Parts 1–5 in order — the main text, all worked examples, Quick Checks, and the Common Confusions box. Skip any box marked Enrichment (collapsible and clearly labeled). This gives you every equation, technique, and concept you need for homework and exams.

Track B (Full, ~40 min): Read everything, including Enrichment boxes (historical context, ionization physics, line broadening details) and Parts 6–7 (planetary atmospheres and climate, assumptions and limitations). Part 6 connects spectroscopy to climate science — it will appear on exams because the physics is the same.

Both tracks cover all core learning objectives. Track B adds depth that connects spectroscopy to some of the most consequential physics on Earth.

A star’s light is an autobiography — if you know how to read it.

In Lectures 1 and 2, you learned to measure a star’s distance, luminosity, temperature, and radius from its brightness and color. But color is blunt: it tells you the overall temperature. Today you gain a scalpel. By spreading starlight into a spectrum — resolving individual wavelengths — you can identify which atoms are in the star’s atmosphere, measure the star’s velocity toward or away from you, and refine the temperature measurement to a precision that color alone cannot achieve.

What you’ll gain: After this reading, every dark line in a stellar spectrum will tell you a story: which element absorbed the photon, what temperature put that element in the right quantum state, and how fast the star is moving. Three independent pieces of information, all from the same observation. And the same physics will explain why Venus is \(460°\text{C}\) while Mars is \(-60°\text{C}\).

Part 1: Kirchhoff’s Laws — Why Stars Show Absorption Spectra

All stars are made of roughly the same stuff — about \(73\%\) hydrogen and \(25\%\) helium by mass. So why do their spectra look so different? Hold this question as you read Parts 1–3. By the end of Part 3, you should be able to answer it quantitatively.

Three Types of Spectra

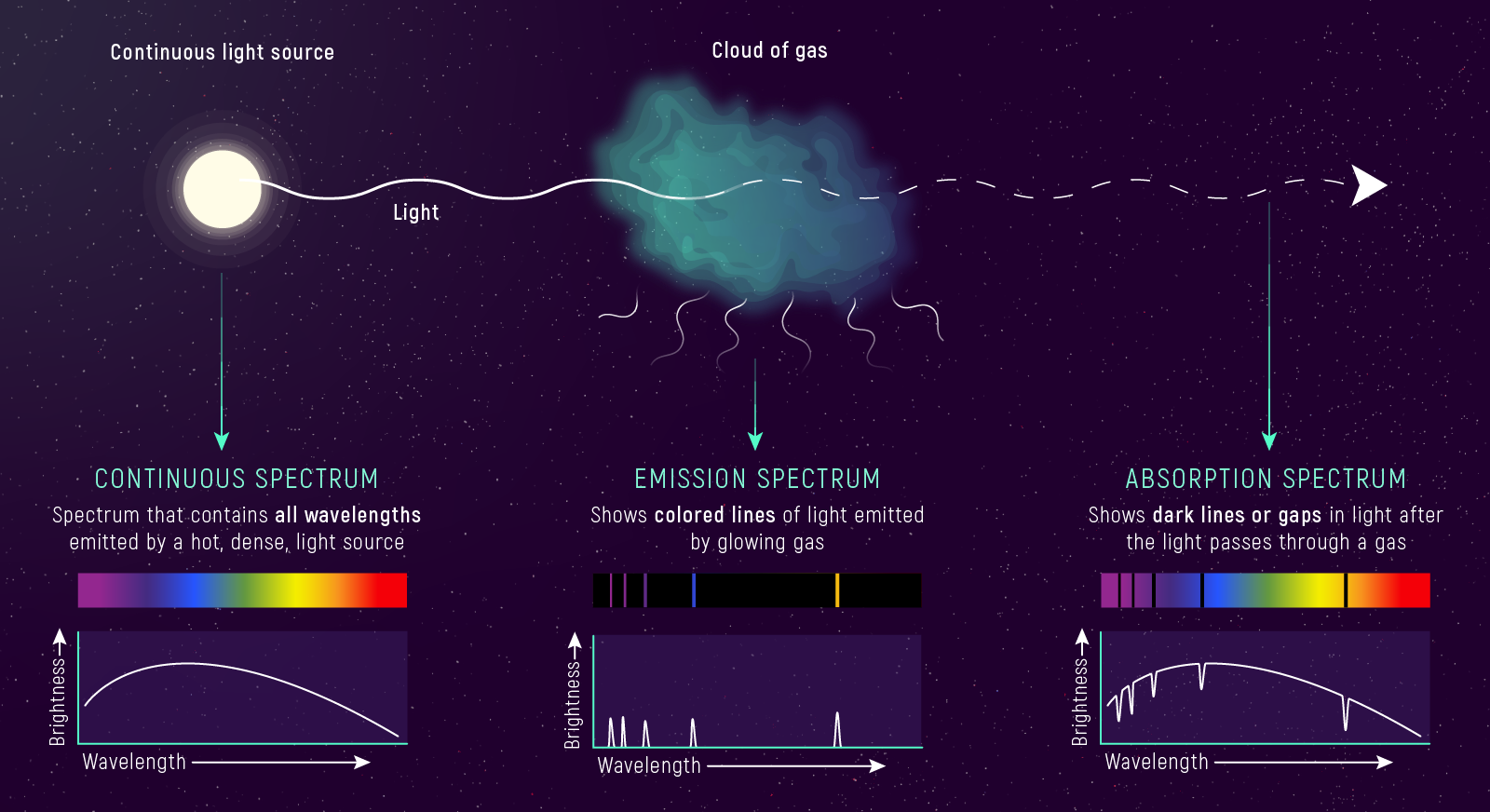

In Lecture 4 (Module 1), you saw a preview of spectral types. Now we formalize the physics. Light sources produce three distinct spectral signatures, depending on their structure:

What to notice: Three spectrum types encode different physics. Continuous = hot dense source. Absorption = cool gas in front of hot source. Emission = hot thin gas. Same atoms, different conditions, different spectra. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

Continuous spectrum (blackbody continuum): A hot, dense source — a solid, liquid, or dense gas — emits light at all wavelengths, producing a smooth rainbow. The shape follows the Planck function \(B_\lambda(T)\) you studied in Lecture 4 (Module 1). Examples: the Sun’s photosphere, an incandescent filament, the interior of a kiln.

Emission spectrum (bright lines on a dark background): A hot, low-density gas emits photons only at specific wavelengths — the wavelengths corresponding to transitions between its atoms’ energy levels. The background is dark; you see isolated bright lines. Examples: nebulae excited by nearby hot stars, neon signs, gas discharge tubes in a teaching lab.

Absorption spectrum (dark lines in a continuous rainbow): A cooler gas in front of a hotter continuum source absorbs photons from the continuum at exactly the wavelengths it would emit if heated. You see the rainbow interrupted by dark lines — a photographic negative of the emission spectrum. Examples: stellar spectra, the solar spectrum (Fraunhofer lines).

Look at the three spectrum descriptions above. For each, write down: (1) the spectrum type, and (2) the physical setup in six words or fewer. Example format: “Continuous — hot, dense source emits all wavelengths.”

Kirchhoff’s Laws of Spectroscopy

These three observations codify into Kirchhoff’s laws:

- A hot, dense object emits a continuous spectrum — all wavelengths, shaped by \(B_\lambda(T)\).

- A hot, low-density gas emits an emission-line spectrum — bright lines at wavelengths determined by its atomic composition.

- A cooler gas in front of a hot continuum source produces an absorption-line spectrum — the continuum minus specific wavelengths, at the same positions the gas would emit if heated.

In practice, you work Kirchhoff’s laws backwards: given a spectrum, infer the physical configuration. Dark lines in a rainbow? → cooler gas in front of a hotter continuum. Bright lines on a dark background? → hot, tenuous gas with no bright continuum behind it. This is the skill you’ll use for the rest of the course.

- Observable: We see dark lines at specific wavelengths in a star’s spectrum

- Model: Kirchhoff’s third law — a cooler atmosphere absorbs from a hotter photosphere

- Inference: The star has a hot dense interior (continuous source) surrounded by a cooler atmosphere (absorbing layer)

Why Stars Show Absorption Spectra: The Two-Layer Model

A star has a steep temperature gradient. Deep in the interior, temperatures reach millions of kelvin. The photosphere — the visible “surface,” meaning the depth where the star becomes opaque (optical depth \(\tau \approx 1\)) — sits at thousands of kelvin (about \(5{,}800\ \text{K}\) for the Sun). Just above the photosphere lies the stellar atmosphere, a thin layer of gas that is slightly cooler than the photosphere below it.

The light we observe is emitted by the photosphere (Kirchhoff’s law 1 → continuous spectrum). As this light travels outward through the cooler stellar atmosphere, atoms in the atmosphere absorb photons at their characteristic wavelengths (Kirchhoff’s law 3 → dark absorption lines appear). The result: a continuous spectrum scored by dark absorption lines.

What to notice: Different wavelengths form at different depths in the photosphere, so absorption lines encode atmospheric structure, not just composition. (Credit: cococubed.com)

You’ll see the evidence in Parts 3 and 4, but plant these flags now so you don’t build the wrong mental model:

Myth 1: “Spectral type tells me what a star is made of.” It doesn’t — not directly. Spectral type primarily reflects temperature. Stars of wildly different spectral types have nearly identical compositions. Part 3 explains why.

Myth 2: “A redshifted star looks red.” It doesn’t. “Redshift” means spectral lines shift to longer wavelengths — a fractional change of \({\sim}0.01\%\). A blue O star receding from you is still blue. Part 4 makes this quantitative.

The photosphere is hot enough to radiate a continuous spectrum, but it is surrounded by a cooler layer — the atmosphere — that absorbs specific colors. This is a natural consequence of stellar structure: temperature decreases outward. If a star had no atmosphere, we’d see a pure blackbody. If we observed only the atmosphere (lit from behind), we’d see emission lines. We see absorption because we look through the atmosphere at the photosphere.

Nebulae — vast clouds of gas — show bright emission lines rather than absorption lines. Why? There’s no dense, hot blackbody source sitting behind them. Instead, ultraviolet photons from a nearby hot star ionize the gas. When electrons recombine with ions and cascade down through energy levels, they emit photons at characteristic wavelengths. This is Kirchhoff’s law 2: a hot, low-density gas emitting an emission-line spectrum.

The Orion Nebula glows red from hydrogen’s Hα line (\(656.3\ \text{nm}\)) and blue-green from doubly ionized oxygen’s [O III] line (\(500.7\ \text{nm}\)). Every color in a nebula photograph encodes a specific atomic transition.

- You observe a smooth rainbow with no dark lines. What type of source are you looking at?

- You observe bright colored lines on a dark background. What produces this?

- You observe a rainbow interrupted by dark lines at specific wavelengths. What’s happening physically?

- A hot, dense source (Kirchhoff’s law 1) — like an incandescent filament or a star’s photosphere viewed without its atmosphere.

- A hot, low-density gas (Kirchhoff’s law 2) — like a nebula or gas discharge tube.

- A cooler gas absorbing from a hotter continuum (Kirchhoff’s law 3) — like a stellar atmosphere in front of its photosphere. The dark lines tell you which atoms are in the cool gas.

Part 1 takeaway: Kirchhoff’s three laws connect the appearance of a spectrum to the physical conditions of the source. Stars produce absorption spectra because their cooler atmospheres absorb from the hotter photosphere — and those dark lines are the key to everything that follows.

Clue 0: The shape of the spectrum (continuous vs. lines, absorption vs. emission) tells you the physical setup of the source — hot dense interior, cool atmosphere, or excited gas cloud.

Check Yourself

Before reading further, make sure you can answer:

- What determines whether you observe an emission or absorption spectrum from a gas? (Answer: whether the gas is viewed against a hotter continuum background or against a dark background.)

- Why does a star show dark absorption lines rather than bright emission lines?

- Would you expect a glowing neon sign to show absorption or emission lines?

Part 2: Spectral Lines as Atomic Fingerprints

The Bohr Model and Discrete Energy Levels

Why do atoms absorb and emit at specific wavelengths rather than at all wavelengths? The answer comes from quantum mechanics: electrons in an atom occupy discrete energy levels — quantized rungs on an energy ladder. They cannot hover between rungs.

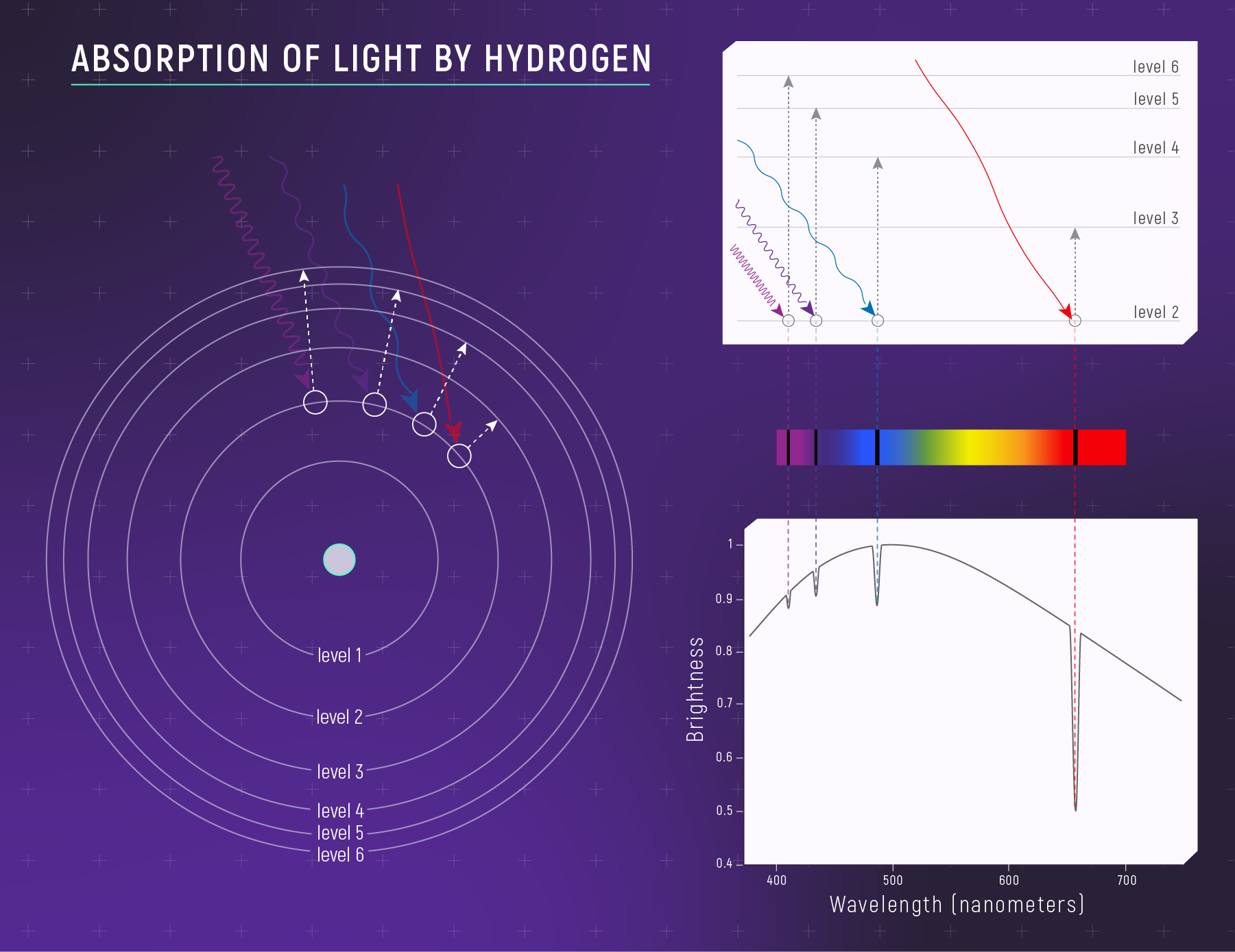

What to notice: Hydrogen absorbs specific wavelengths because electrons jump UP between quantized energy levels. Each dark line = one electron transition. E = hν determines which wavelengths. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

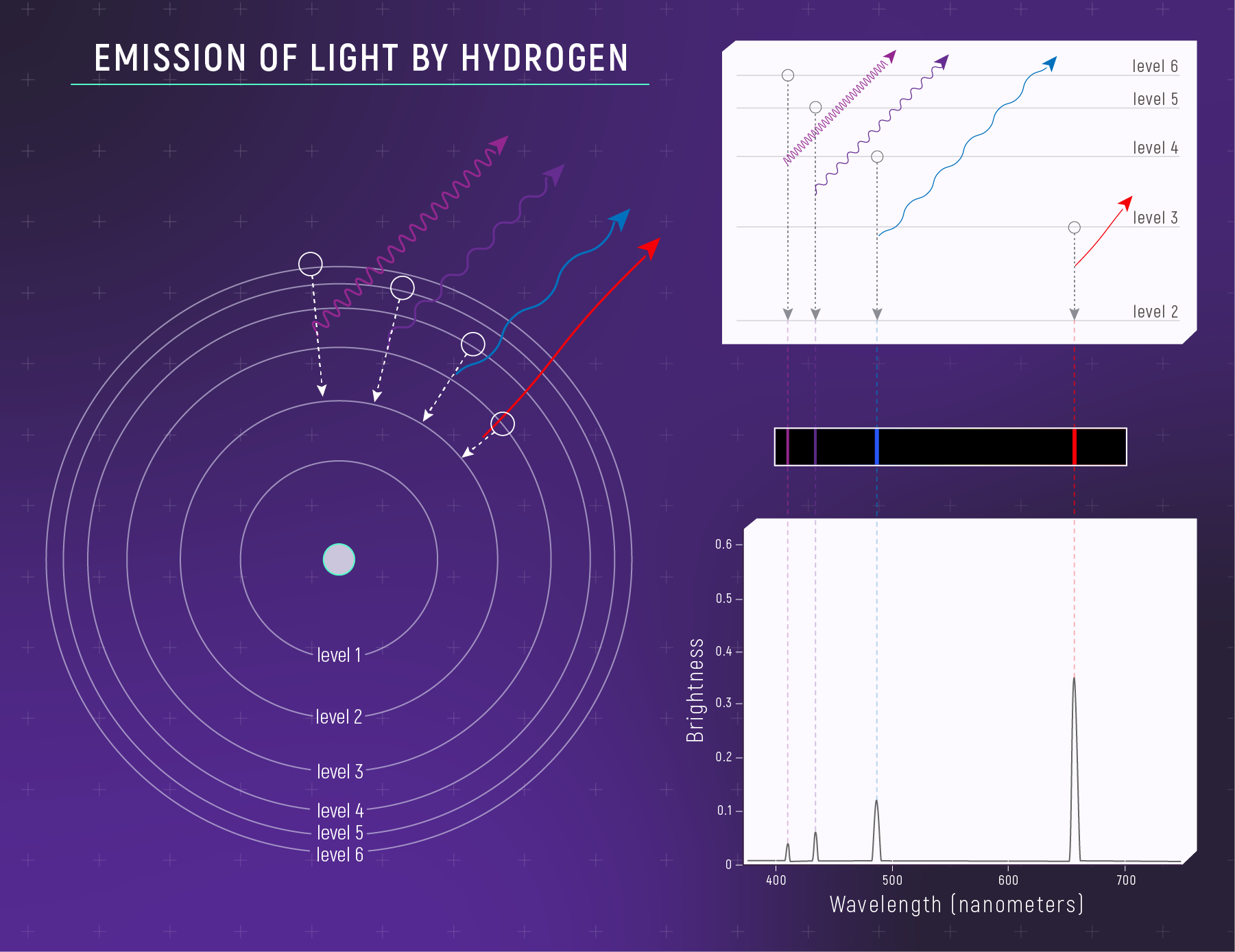

Now look at the reverse process — what happens when excited electrons fall back down through the energy levels:

What to notice: Hydrogen emits specific wavelengths because electrons fall DOWN between energy levels. Each bright line = one electron transition. The Balmer series (visible) comes from transitions to level 2. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

The same energy gaps produce the same wavelengths whether the photon is absorbed (electron jumps up) or emitted (electron falls down). This is why absorption and emission lines appear at identical wavelengths — a fact that Kirchhoff noticed empirically decades before quantum mechanics explained it.

The Bohr model (1913) captures the essential idea for hydrogen. The energy of the \(n\)-th level is:

\[ E_n = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{n^2} \tag{1}\]

where \(n = 1, 2, 3, \ldots\) is the principal quantum number and \(13.6\ \text{eV}\) is the ionization energy of hydrogen — the energy needed to completely free the electron.

Key observations from this equation:

- \(n = 1\) (ground state): \(E_1 = -13.6\ \text{eV}\) — the most tightly bound level (most negative energy)

- \(n = 2\) (first excited state): \(E_2 = \frac{-13.6\ \text{eV}}{2^2} = -3.4\ \text{eV}\) — less tightly bound

- As \(n\) increases: levels crowd together and approach \(E = 0\) (the ionization threshold, where the electron is free)

- Negative sign: means the electron is bound. You must add energy to free it.

Use \(E_n = -13.6\ \text{eV}/n^2\) to compute \(E_4\). What is the energy gap \(\Delta E\) between \(n = 4\) and \(n = 2\), in eV? Convert that energy to a wavelength using \(\lambda = hc/\Delta E\) with \(hc = 1.986 \times 10^{-16}\ \text{erg·cm}\) and \(1\ \text{eV} = 1.602 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}\). What color does that correspond to? (Check your answer against the Balmer series table below.)

When an electron transitions between levels, it either absorbs or emits a photon whose energy equals the difference between the two levels:

\[\Delta E = |E_{\text{upper}} - E_{\text{lower}}|\]

The photon’s wavelength is set by the energy-wavelength relation:

\[ E = h\nu = hc\lambda^{-1} \tag{2}\]

Rearranging for wavelength: \(\lambda = hc / \Delta E\).

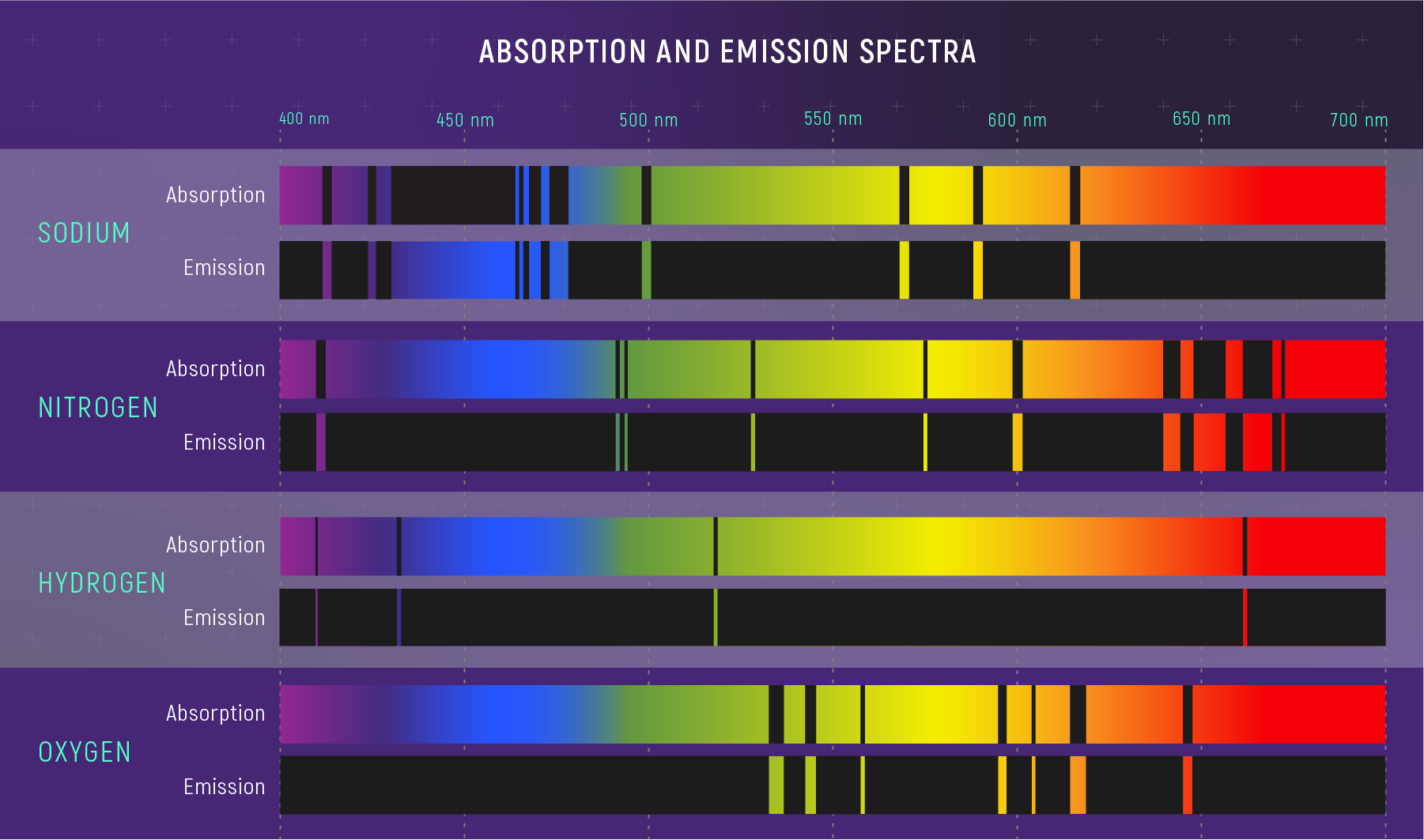

This is the key insight: each transition produces a photon at a specific wavelength, determined entirely by the energy gap between levels. Different elements have different energy-level structures (different nuclear charges, different electron configurations), so each element produces a unique set of spectral lines — a fingerprint as distinctive as DNA.

What to notice: Each element has a unique spectral fingerprint. The dark lines in absorption exactly match the bright lines in emission—same energy transitions, opposite directions. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

The Hydrogen Balmer Series: Visible Fingerprints

The most famous set of spectral lines in astronomy is the Balmer series — transitions where electrons fall to (emission) or jump from (absorption) the \(n = 2\) level in hydrogen:

| Transition | Name | Wavelength (nm) | Color |

|---|---|---|---|

| \(n = 3 \to 2\) | H\(\alpha\) | 656.3 | Deep red |

| \(n = 4 \to 2\) | H\(\beta\) | 486.1 | Blue-green |

| \(n = 5 \to 2\) | H\(\gamma\) | 434.0 | Violet |

| \(n = 6 \to 2\) | H\(\delta\) | 410.2 | Near-UV |

These four lines are the most prominent features in the visible spectra of many stars. They fall in the visible range because the energy differences (\(\sim 1.9\text{–}3.0\ \text{eV}\)) correspond to the energy of visible photons.

The \(n = 3 \to 2\) transition releases \(\Delta E = 1.89\ \text{eV}\). Using \(\lambda = hc/\Delta E\), this corresponds to \(656\ \text{nm}\) — deep red light. The energy of the transition sets the color. There’s nothing special about red — it’s just where the Bohr model’s arithmetic lands for this particular gap.

Problem: Use the Bohr model to predict the wavelength of the \(n = 3 \to 2\) transition in hydrogen. Compare to the observed H\(\alpha\) wavelength of \(656.3\ \text{nm}\).

Solution:

Step 1 — Find the energy levels. \[E_3 = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{3^2} = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{9} = -1.511\ \text{eV}\] \[E_2 = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{2^2} = -\frac{13.6\ \text{eV}}{4} = -3.400\ \text{eV}\]

Step 2 — Compute the energy difference. \[\Delta E = |E_3 - E_2| = |-1.511\ \text{eV} - (-3.400\ \text{eV})| = 1.889\ \text{eV}\]

Step 3 — Convert to CGS. (\(1\ \text{eV} = 1.602 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}\)) \[\Delta E = 1.889\ \text{eV} \times 1.602 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg/eV} = 3.026 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}\]

Step 4 — Apply \(\lambda = hc / \Delta E\). \[\lambda = \frac{(6.626 \times 10^{-27}\ \text{erg·s})(2.998 \times 10^{10}\ \text{cm/s})}{3.026 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}}\] \[\lambda = \frac{1.986 \times 10^{-16}\ \text{erg·cm}}{3.026 \times 10^{-12}\ \text{erg}} = 6.56 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{cm}\]

Step 5 — Convert to nm. (\(1\ \text{cm} = 10^7\ \text{nm}\)) \[\lambda = 6.56 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{cm} \times 10^7\ \text{nm/cm} = 656\ \text{nm}\ \checkmark\]

\[[\lambda] = \frac{[\text{erg·s}][\text{cm/s}]}{[\text{erg}]} = \frac{\text{erg·cm}}{\text{erg}} = \text{cm}\ \checkmark\]

Interpretation: The Bohr model predicts H\(\alpha\) at \(656\ \text{nm}\) — within \(0.3\ \text{nm}\) of the precise laboratory value (\(656.28\ \text{nm}\)). The small difference comes from rounding the ionization energy to \(13.6\ \text{eV}\); the exact Rydberg value is \(13.5984\ \text{eV}\). This close agreement was one of the Bohr model’s great early triumphs. The energy gap between \(n = 3\) and \(n = 2\) is \(1.89\ \text{eV}\), which corresponds to deep red visible light — the same red glow you see in photographs of emission nebulae.

The full CGS unit grind above is good practice, but there’s a faster path. The product \(hc\) in convenient units is:

\[hc \approx 1240\ \text{eV·nm}\]

So for any transition with energy gap \(\Delta E\) (in eV), the wavelength is simply \(\lambda\ (\text{nm}) \approx \frac{1240\ \text{eV·nm}}{\Delta E\ (\text{eV})}\). For H\(\alpha\): \(\lambda \approx \frac{1240\ \text{eV·nm}}{1.89\ \text{eV}} \approx 656\ \text{nm}\) — same answer, one line. Use the CGS derivation when you need to show your work; use this shortcut for quick estimates and sanity checks. For this course, \(hc \approx 1240\ \text{eV·nm}\) is your default tool — use it freely unless a problem explicitly asks for CGS.

In Lecture 4 (Module 1), you learned that blackbody radiation produces a continuous spectrum described by \(B_\lambda(T)\). Now you’re learning that atoms produce discrete lines at specific wavelengths. A real stellar spectrum is both: a continuous Planck curve (from the photosphere) with discrete absorption lines carved into it (by the atmosphere). The Planck curve gives you temperature (via Wien’s law); the lines give you composition and velocity. Two tools from one observation.

What to notice: A real stellar spectrum combines continuous (blackbody) shape with absorption lines. The overall curve gives temperature (Wien); the lines give composition (spectroscopy). Two inference tools in one observation. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

- An absorption line appears at \(486.1\ \text{nm}\) in a star’s spectrum. Which element and which transition does this correspond to?

- If a hydrogen atom’s electron jumps from \(n = 1\) to \(n = 3\), does the atom absorb or emit a photon? Is this photon in the visible range?

- Why can’t hydrogen atoms absorb photons at any arbitrary wavelength?

- Hydrogen, H\(\beta\) (\(n = 4 \to 2\) or \(n = 2 \to 4\)). The wavelength \(486.1\ \text{nm}\) is the second Balmer line.

- Absorbs — the electron moves to a higher energy level. The energy gap \(|E_3 - E_1| = |-1.51\ \text{eV} - (-13.6\ \text{eV})| = 12.09\ \text{eV}\) corresponds to \(\lambda = hc/\Delta E \approx 102.6\ \text{nm}\) — deep ultraviolet, not visible. This is the Lyman series (\(n = 1 \to 3\), Ly\(\beta\)).

- Because energy levels are quantized — the electron can only occupy specific energies. A photon must have exactly the right energy (matching a level gap) to be absorbed (absorption is upward: the electron moves to a higher level). A photon at a “wrong” wavelength passes through unabsorbed.

Part 2 takeaway: Atoms absorb and emit photons at specific wavelengths because electrons occupy discrete energy levels. Each element’s unique level structure creates a unique spectral fingerprint. By matching observed absorption lines to laboratory wavelengths, we identify which elements are present in a star’s atmosphere — without ever visiting the star.

Clue 1: The positions of absorption lines (which wavelengths are dark) tell you which elements are in the star’s atmosphere — each element’s fingerprint is unique.

Part 3: The OBAFGKM Sequence — Temperature, Not Composition

A Temperature Sequence in Disguise

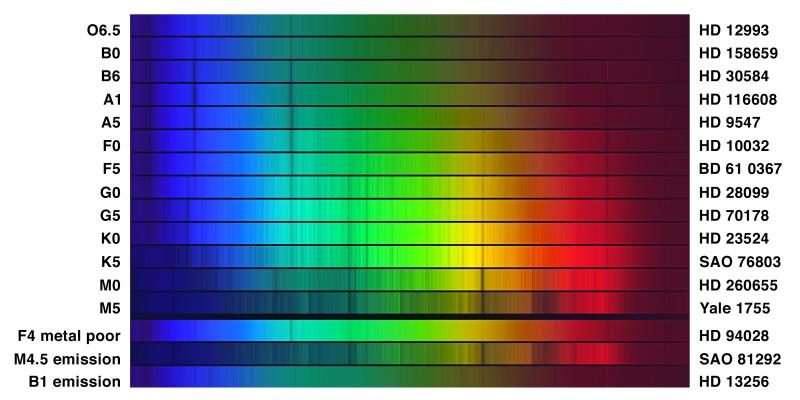

In the early 1900s, astronomers at Harvard Observatory — led by Annie Jump Cannon and Williamina Fleming — classified hundreds of thousands of stellar spectra by eye, sorting them by the appearance and strength of their spectral lines into categories labeled with letters. After much rearranging, the sequence settled into: O, B, A, F, G, K, M — from strongest helium lines to strongest molecular bands.

The classic mnemonic: “Oh Be A Fine Guy/Girl, Kiss Me.”

The breakthrough came when Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin showed in her 1925 PhD thesis — arguably the most important doctoral dissertation in the history of astronomy — that stars are overwhelmingly composed of hydrogen and helium, and that the spectral sequence is fundamentally a temperature sequence, not a composition sequence. This was so radical that her advisor, Henry Norris Russell, initially urged caution (he later acknowledged she was right). The composition of stars is remarkably uniform (about \(74\%\) hydrogen, \(25\%\) helium, \(1\text{–}2\%\) heavier elements by mass). What changes along the sequence is not what atoms are present but which quantum states those atoms occupy — and that depends on temperature.

What to notice: The spectral sequence from O (top, hottest) to M (bottom, coolest). Dark absorption lines shift across the sequence — hydrogen Balmer lines peak at A-type, helium lines dominate O and B, metal lines crowd in at G and K, and molecular bands appear at M. The bottom three rows show special cases: a metal-poor F star, an M star with emission lines, and a B star with emission. (Credit: NOAO/AURA/NSF)

| Spectral Type | Color | Temperature Range | Main-Sequence Prevalence | Dominant Spectral Features | Example |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | Blue-violet | \(\gtrsim 30{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(0.00003\%\) | He II (ionized helium), weak H | O4I (\(\zeta\) Puppis), O9.5V (10 Lac) |

| B | Blue-white | \(10{,}000\)–\(30{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(0.13\%\) | He I (neutral helium), strong H | B8Ia (Rigel), B1III (Spica) |

| A | White | \(7{,}500\)–\(10{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(0.6\%\) | Strongest H Balmer lines | A1V (Sirius), A0V (Vega) |

| F | Yellow-white | \(6{,}000\)–\(7{,}500\ \text{K}\) | \(3\%\) | Moderate H, weak metals | F5IV (Procyon A) |

| G | Yellow | \(5{,}200\)–\(6{,}000\ \text{K}\) | \(7.6\%\) | Weak H, strong metal lines (Ca, Fe) | G2V (Sun) |

| K | Orange | \(3{,}700\)–\(5{,}200\ \text{K}\) | \(12.1\%\) | Very weak H, strong metals, molecular bands appear | K1.5III (Arcturus) |

| M | Red-orange | \(\lesssim 3{,}700\ \text{K}\) | \(76.5\%\) | Molecular bands (TiO), very weak H | M2Ia (Betelgeuse), M5V (Proxima Cen) |

Several of these examples are giants or supergiants rather than main-sequence dwarfs — those are the ones bright enough to have names. The prevalence column refers to main-sequence stars only.

Look at the prevalence column: M dwarfs make up over three-quarters of all main-sequence stars, yet they’re too faint to see with the naked eye. The bright stars that fill constellations — Rigel (B supergiant), Sirius (A dwarf), Arcturus (K giant) — are the rare luminous ones. The galaxy is dominated by cool, dim, long-lived M dwarfs.

Why Temperature Controls Line Strength

This is a critical conceptual point that trips up beginners: the spectral type does NOT directly reflect composition. All main-sequence stars have roughly the same composition. What changes is which atomic transitions are active — and that depends on temperature through the Boltzmann distribution.

A stellar spectrum encodes multiple independent properties. Here’s how to read them:

| What You Measure | What It Tells You |

|---|---|

| Line positions (which wavelengths are dark) | Composition — which elements are present |

| Line strength pattern (which species dominate) | Temperature → spectral type (OBAFGKM) |

| Line widths (narrow vs. broad) | Surface gravity/rotation → luminosity class |

| Metal line forest (amplitude relative to H) | Metallicity (heavy-element abundance) |

Temperature is the dominant knob — it controls line strengths so powerfully that it can mask composition differences entirely.

For an atom to absorb a photon at a given wavelength, an electron must already be in the right starting energy level. The fraction of atoms in any given level depends on temperature through the Boltzmann distribution:

\[\text{fraction in level } n \propto e^{-\chi_n / k_B T}\]

where \(\chi_n\) is the excitation energy — the energy above the ground state needed to reach level \(n\) (always positive) — and \(k_B = 8.617 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{eV/K}\) is Boltzmann’s constant. For hydrogen, \(\chi_2 = 10.2\ \text{eV}\) (the energy to excite from \(n = 1\) to \(n = 2\)). Note that \(\chi_n\) is not the same as the Bohr energy \(E_n\) used earlier — it’s the gap \(\chi_n = E_n - E_1\), which is always positive.

The exponential is ruthless: even modest temperature changes dramatically shift which levels are populated. Higher excitation energy \(\chi_n\) demands higher temperature for significant population. As a rough guide, every factor-of-two increase in temperature can boost high-energy level populations by orders of magnitude — the exponential amplifies what a linear function would barely notice.

Temperature controls which lines you see. A cool star and a hot star can have identical compositions — but their spectra look completely different because the Boltzmann factor decides which energy levels are occupied.

(More precisely, the full Boltzmann expression includes degeneracy factors \(g_n\) and a partition function in the denominator, but the key physics — exponential sensitivity to \(\chi_n/k_BT\) — is captured by the expression above.)

All stars are \({\sim}73\%\) hydrogen. Hydrogen Balmer absorption requires electrons already in \(n = 2\), which is \(10.2\ \text{eV}\) above the ground state. At what type of star — O, A, G, or M — would you expect the strongest Balmer lines, and why? Commit to an answer before reading on.

How this creates the spectral sequence:

O stars (\(30{,}000{+}\ \text{K}\)): So hot that collisions ionize most hydrogen atoms — electrons are stripped free entirely. No neutral hydrogen means weak Balmer lines. Instead, we see lines of ionized helium (He II), which requires extreme temperatures to produce. The spectrum is dominated by ions. (The physics governing ionization is described by the Saha equation, which we won’t derive here — but the key idea is simple: at high enough temperatures, collisions have enough energy to knock electrons free entirely.)

A stars (\(7{,}500\text{–}10{,}000\ \text{K}\)): The Goldilocks temperature for hydrogen Balmer absorption. The Balmer line strength reflects a competition between excitation and ionization: the Boltzmann factor tells us what fraction of neutral atoms are in \(n = 2\), but the Saha equation tells us what fraction of atoms are neutral at all. At A-star temperatures, enough hydrogen remains neutral and enough of that neutral hydrogen is excited to \(n = 2\) that Balmer absorption is maximally efficient. H lines are at their strongest here. Helium lines are weakening (not hot enough for He excitation); metal lines are not yet prominent (too hot for many metal ions to survive un-ionized in the right states).

G stars (\(5{,}800\ \text{K}\), like the Sun): Balmer lines are visible but weaker — fewer atoms sit in \(n = 2\) at this temperature. Metal absorption lines become prominent: ionized calcium (Ca II H & K lines at \(393.4\) and \(396.8\ \text{nm}\)), neutral iron (many lines), sodium (the D lines at \(589.0\) and \(589.6\ \text{nm}\)). The spectrum looks like a forest of metallic lines.

M stars (\(< 3{,}700\ \text{K}\)): So cool that atoms remain neutral and even molecules form. Titanium oxide (TiO) produces broad absorption bands that dominate the red and infrared spectrum. Hydrogen Balmer lines are very weak because almost no atoms are in the \(n = 2\) state at these temperatures.

Do O stars have more helium than M stars? No — roughly the same composition. But the extreme temperature ionizes hydrogen and excites helium transitions.

Do A stars have more hydrogen than M stars? No — similar abundance. But A-star temperatures put a large fraction of hydrogen atoms in the \(n = 2\) state, making Balmer absorption maximally efficient.

This is why spectral type \(\approx\) effective temperature. A low-metallicity O star and a high-metallicity O star at the same temperature would have very similar spectral types.

Your lab partner claims: “M stars have weak hydrogen lines because they have less hydrogen than A stars.” Construct a counterargument using the Boltzmann distribution and the concept of energy-level populations. What fraction of hydrogen atoms are in \(n = 2\) at \(3{,}000\ \text{K}\) vs. \(10{,}000\ \text{K}\)?

Punchline (order-of-magnitude): At \(3{,}000\ \text{K}\), \(k_BT \approx 0.26\ \text{eV}\), so \(e^{-10.2\ \text{eV}/0.26\ \text{eV}} \sim 10^{-17}\) — essentially zero atoms in \(n = 2\). At \(10{,}000\ \text{K}\), \(k_BT \approx 0.86\ \text{eV}\), so \(e^{-10.2\ \text{eV}/0.86\ \text{eV}} \sim 10^{-5}\) — a tiny but significant fraction. That’s a factor of \(\sim 10^{12}\) difference in the Boltzmann factor, with zero change in hydrogen abundance.

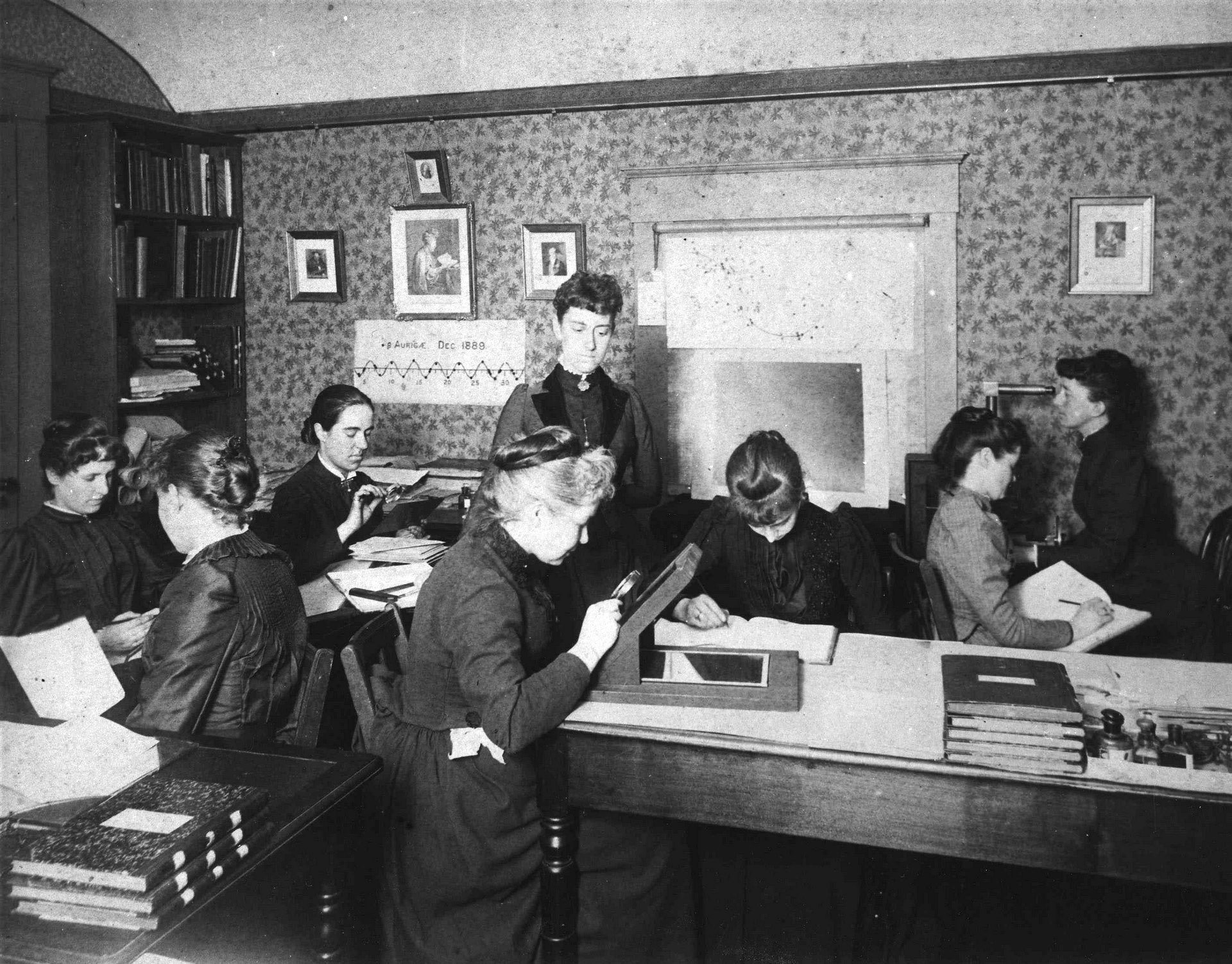

The Industrial Data Problem

The OBAFGKM sequence didn’t fall from the sky. It was built — by hand, from glass.

By the 1880s, two technologies had converged to create an unprecedented data bottleneck. Spectroscopy, pioneered by Kirchhoff and Bunsen (1859), had shown that dark lines in stellar spectra encode chemical information. Photographic plates, unlike the human eye, could accumulate photons over hours and record spectra permanently. Harvard Observatory alone amassed over 500,000 glass plates — millions of stellar spectra, frozen in silver halide, waiting to be classified. Reading them required a workforce. That workforce would come from a pool of talent that the scientific establishment had otherwise excluded.

Working Conditions and Structural Inequity

Director Edward Pickering hired women as “computers” — not out of progressive conviction, but because they were available, educated, and cheap. College-educated women, largely shut out of faculty positions, teaching appointments, and telescope time, could be hired at 25–50 cents per hour — less than Harvard paid its secretaries, and far less than male assistants earned. Pickering reportedly declared that “even my Scottish maid could do better” than his male staff, then hired that maid: Williamina Fleming.

What to notice: These women analyzed hundreds of thousands of stellar spectra from photographic plates, discovering the patterns (OBAFGKM, period-luminosity relation, luminosity classification) that transformed astronomy into astrophysics. (Credit: Harvard College Observatory / Smithsonian Institution)

The working conditions were plain. The women were classified as staff, not researchers. They were denied access to telescopes — some explicitly, others by social convention (“propriety” barred women from observing at night). They were rarely listed as authors on publications that used their work. Public credit came inconsistently, often filtered through male supervisors. They worked in a room at the observatory, hunched over glass plates with magnifying loupes, hand-recording spectral features into catalogs. There was no automation. Every classification was a human judgment.

And yet: within these constraints, they did science that redefined the field.

The Intellectual Breakthroughs

Classification was not clerical work. It required recognizing subtle differences in line patterns across noisy photographic data — detecting structure by eye that no theory yet predicted. This was statistical pattern recognition before formal statistics, physical interpretation without quantum mechanics.

- Williamina Fleming developed the first photographic spectral classification system, discovered 310 variable stars, 10 novae, and the Horsehead Nebula, and became Harvard’s Curator of Astronomical Photographs.

- Annie Jump Cannon classified over 350,000 stellar spectra — roughly three per minute — and reordered the classification letters into the OBAFGKM temperature sequence you just learned. Despite her deafness and the discrimination she faced, she became the first woman officer of the American Astronomical Society.

- Henrietta Swan Leavitt discovered the period-luminosity relation for Cepheid variable stars (1912), which became the foundation for measuring cosmic distances and enabled Hubble’s later discovery of the expanding universe.

- Antonia Maury noticed that spectral line widths varied systematically among stars of the same spectral type — later understood as luminosity classification (the Roman numeral in “G2V”). Her insistence on physical interpretation over rapid cataloging clashed with Pickering’s production-line priorities. She was right.

These women built the empirical dataset that made astrophysics possible. Their classifications were so precise that they demanded physical explanation — and that explanation came:

- 1925: Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin used the Harvard classifications to prove that stars are overwhelmingly hydrogen and helium — the result her advisor Russell initially called “clearly impossible” before later acknowledging she was correct.

- 1920s: Eddington’s stellar interior models explained the OBAFGKM sequence as a temperature progression.

- 1938: Bethe’s nuclear fusion theory completed the picture, explaining why stars at different temperatures produce different spectra.

The data came first. The theory followed. This is how science usually works, even when textbooks present it the other way around.

From Glass Plates to Algorithms

The 500,000 glass plates at Harvard were the “big data” of the 19th century. Today, spectroscopic surveys like SDSS and LAMOST classify millions of stellar spectra using automated pipelines and machine learning. CCD detectors — developed in part because astronomers needed more sensitive light collectors than photographic emulsions — replaced glass plates in the 1980s. Signal-processing techniques refined for extracting faint spectral features from noise now underpin applications from radio astronomy to medical imaging.

But the core intellectual act is unchanged: detecting meaningful patterns in noisy spectral data. What Cannon did by eye at three spectra per minute, a modern pipeline does at thousands per second. The speed changed. The science didn’t.

The Societal Return

Astronomy doesn’t happen in a vacuum. The demand to measure faint, distant signals under extreme conditions has repeatedly driven tool development that finds applications far beyond the observatory.

The need for more sensitive detectors pushed CCD technology forward in the 1970s–80s, accelerating the digital imaging revolution that produced modern camera sensors. Signal-processing techniques developed to extract faint spectral features from noisy radio data influenced broader developments in wireless communications and data processing. The radiative transfer equations that model how photons travel through stellar atmospheres are the same equations used today to model Earth’s climate, optimize solar cell efficiency, and plan radiation therapy for cancer treatment. And the general relativity you’ll encounter later in this course — the physics that bends light around black holes — is the same physics that GPS satellites use to keep your position accurate to within meters.

World War II accelerated this exchange. Radar technology became radio astronomy, revealing neutral hydrogen’s 21 cm emission line (1951). Electronic detectors from military applications replaced photographic plates, increasing sensitivity a hundredfold. Rockets designed for warfare carried the first ultraviolet and X-ray spectrographs above Earth’s atmosphere, opening spectral windows that the ground could never access.

The pattern is consistent: astronomers build mathematical and instrumental tools to solve extreme measurement problems, and those tools turn out to be what engineers and physicians need in completely different contexts. The spectroscopy you’re learning in this reading has a direct line from Kirchhoff’s 1859 laboratory through the Harvard Computers’ glass plates to the JWST spectra of exoplanet atmospheres — and outward to climate models, medical imaging, and satellite navigation.

Why This Matters in This Course

The OBAFGKM sequence you just learned was not derived from theory. It was built from data — by women working under conditions of structural inequity, using tools no more sophisticated than magnifying glasses and hand-written catalogs. The Boltzmann distribution and Saha equation you studied above came later, explaining why their empirical temperature sequence exists. This is Observable → Model → Inference in its purest historical form: the pattern was observed first, and the physics was built to explain it.

Metallicity: A Secondary Effect

Metallicity (\(Z\)) is the mass fraction of elements heavier than helium. The Sun has \(Z_\odot \approx 0.014\) — about \(1.4\%\) of its mass is “metals” (everything heavier than He, in astronomical parlance; older references cite \(Z_\odot \approx 0.02\), but modern measurements have revised this downward). High-metallicity stars show more and stronger metal absorption lines; low-metallicity stars appear “cleaner.” But metallicity is a second-order effect for classification. Two stars at the same temperature with different metallicities have the same spectral type — the metal line strengths differ, but the overall pattern (which species dominates) is set by temperature.

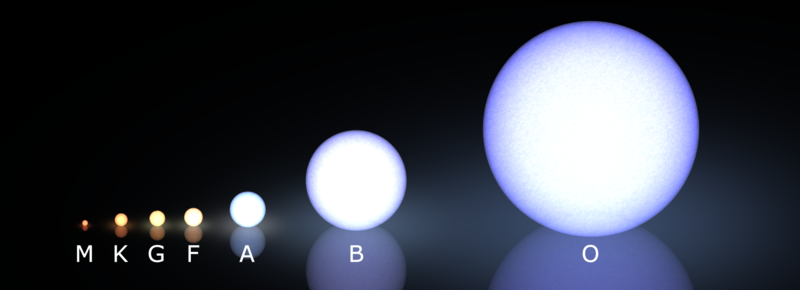

The spectral type (OBAFGKM) tells you temperature. But stars of the same temperature can have wildly different luminosities — a G2 main-sequence star like the Sun (\(L \approx 1\,L_\odot\)) and a G2 supergiant (\(L \approx 10{,}000\,L_\odot\)) look very different despite having similar surface temperatures. The missing piece is luminosity class, which encodes surface gravity and therefore evolutionary state.

The Morgan–Keenan (MK) system combines both into a compact label: spectral type + luminosity class. A star labeled G2V is not just “yellow” — it has a specific effective temperature (\({\sim}5{,}770\ \text{K}\)) and a main-sequence surface gravity (\(\log g \approx 4.4\)).

What to notice: Main-sequence stars span a huge range of size and color. M dwarfs (left) are small and red-orange; O stars (right) are large and blue-white. But size on the main sequence is just one dimension — a red supergiant can dwarf an O star despite being cooler. (Credit: Wikimedia Commons (after Morgan & Keenan))

| Luminosity Class | Description | Physical Meaning |

|---|---|---|

| 0 / Ia+ | Hypergiant | Most extreme supergiants; very rare |

| Ia | Luminous supergiant | Massive evolved stars; low surface gravity |

| Ib | Less-luminous supergiant | Evolved, but less extreme than Ia |

| II | Bright giant | Intermediate between supergiants and giants |

| III | Giant | Evolved off main sequence; expanded envelope |

| IV | Subgiant | Transitioning from main sequence to giant branch |

| V | Main-sequence (dwarf) | Core hydrogen burning; where stars spend most of their lives |

| VI | Subdwarf | Below main sequence; typically metal-poor |

| VII | White dwarf | Stellar remnant (rarely used in MK; usually classified separately) |

How is luminosity class determined? From spectral line widths. Giant and supergiant stars have extended, low-density atmospheres, so their spectral lines are narrow (little pressure broadening). Dwarfs have compact, dense atmospheres, so their lines are broader. The same absorption line in a K1III giant (Arcturus) and a K1V dwarf looks noticeably different in width — a trained spectroscopist can read the luminosity class directly from the line profile.

The key insight: You can have an M supergiant (M2Ia, like Betelgeuse) that is far more luminous than a hot O dwarf. Temperature \(\neq\) luminosity. The H–R diagram is a 2D space, and the MK system encodes both axes — spectral type maps to the horizontal axis (temperature), luminosity class maps to the vertical axis (luminosity). It’s a compressed astrophysical state vector.

We’ll use MK classifications extensively when we build the full H–R diagram in Lecture 6.

- Which spectral type has the strongest hydrogen Balmer lines?

- Why are H lines weak in O stars — lack of hydrogen, or something else?

- Two stars have the same spectral type (G5). Must they have the same luminosity?

- A star’s spectrum shows strong TiO molecular bands. Is it hot or cool?

- A — the temperature (\({\sim}8{,}000\text{–}10{,}000\ \text{K}\)) maximally populates the \(n = 2\) level.

- Something else — O stars have plenty of hydrogen, but it’s mostly ionized at \(30{,}000{+}\ \text{K}\). No neutral hydrogen means no Balmer absorption.

- No — same spectral type means similar temperature, but they could be a dwarf (V) or a giant (III) with luminosities that differ by orders of magnitude. That’s why luminosity class exists.

- Cool — molecular bands form only at low temperatures (\(\lesssim 3{,}700\ \text{K}\)), characteristic of M-type stars.

Part 3 takeaway: OBAFGKM is a temperature sequence. Composition is nearly uniform across stars — what changes is which energy levels are populated, and that depends exponentially on temperature. The spectral type of a star tells you its temperature; metallicity and luminosity class add refinement.

Clue 2: The pattern of line strengths — which species dominate and which are absent — tells you temperature (spectral type). Strong Balmer lines? \({\sim}10{,}000\ \text{K}\). TiO bands? Below \({\sim}3{,}700\ \text{K}\). The same element can look invisible or overwhelming depending on temperature alone.

Check Yourself

- State Kirchhoff’s three laws in your own words.

- Why do A stars have the strongest hydrogen Balmer lines? (Your answer should mention the \(n = 2\) energy level and temperature.)

- If you observe a stellar spectrum dominated by molecular TiO bands, what is the approximate spectral type and temperature range?

- A star shows very weak hydrogen Balmer lines. Give two physically distinct reasons (other than “less hydrogen”) why the Balmer lines could be weak.

- Two reasons besides “less hydrogen”: (1) the star is too hot — hydrogen is ionized, so no neutral atoms exist for Balmer absorption (O stars); (2) the star is too cool — almost no hydrogen atoms are excited to the \(n = 2\) level needed for Balmer transitions (M stars). Both are temperature effects, not composition effects.

Part 4: The Doppler Shift — Reading Stellar Motion from Light

The Doppler Effect for Light

You’ve experienced the Doppler effect with sound: an ambulance siren rises in pitch as it approaches and drops as it recedes. Light does the same thing. When a light source moves toward or away from an observer, the observed wavelength shifts.

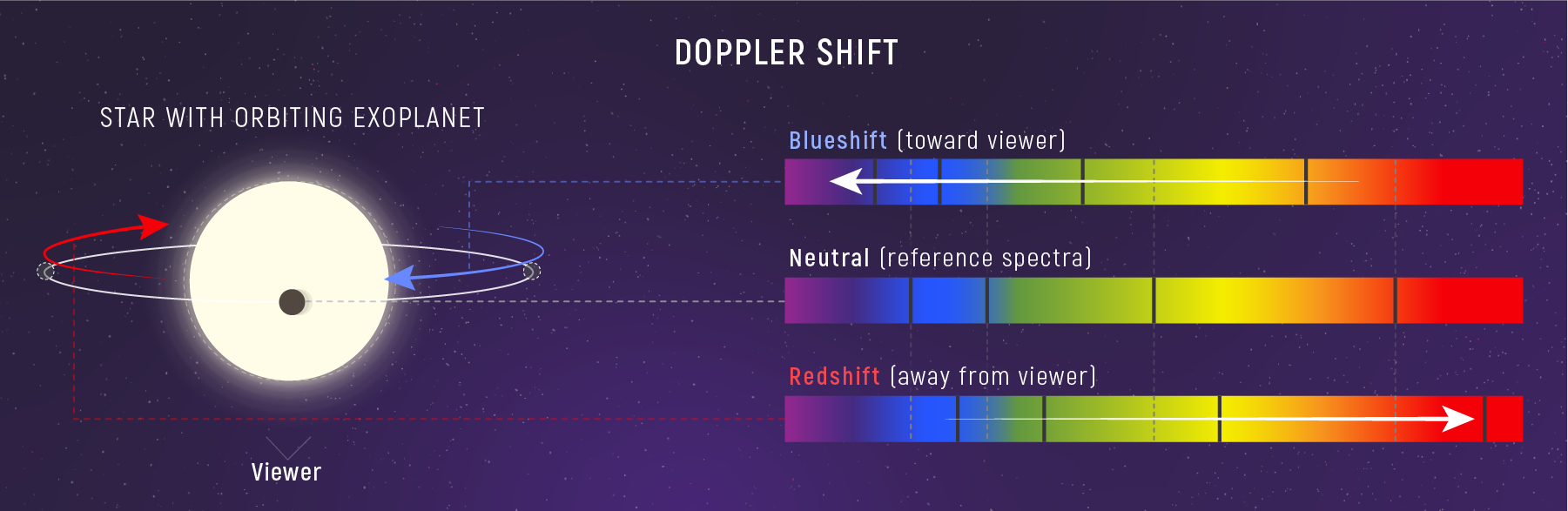

What to notice: Motion toward us compresses wavelengths (blueshift); motion away stretches them (redshift). This lets us measure stellar velocities—and detect exoplanets via the star’s wobble. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

If a source has radial velocity \(v_r\) (positive = receding, negative = approaching), the observed wavelength \(\lambda_{\text{obs}}\) relates to the laboratory rest wavelength \(\lambda_0\) by:

\[ \frac{\Delta \lambda}{\lambda_0} = \frac{v_r}{c} \tag{3}\]

where \(\Delta \lambda = \lambda_{\text{obs}} - \lambda_0\).

Interpretation — shifts tell you direction:

- Redshift (\(\Delta \lambda > 0\), \(\lambda_{\text{obs}} > \lambda_0\)): source receding, \(v_r > 0\)

- Blueshift (\(\Delta \lambda < 0\), \(\lambda_{\text{obs}} < \lambda_0\)): source approaching, \(v_r < 0\)

This formula is valid for \(v_r \ll c\) (the non-relativistic limit), which covers virtually all stellar velocities in our galaxy. Typical stellar radial velocities are \(10\text{–}100\ \text{km/s}\); the speed of light is \(300{,}000\ \text{km/s}\). The ratio \(v_r/c \sim 10^{-4}\) to \(10^{-3}\) — tiny shifts, but measurable with precision spectrographs. For relativistic speeds (galaxies, jets, cosmology), a full relativistic Doppler formula is needed, and for the expanding universe the interpretation becomes cosmological redshift — a stretch of space itself, not simple motion. We’ll revisit this distinction if it arises later in the course. One crucial diagnostic: a real Doppler shift moves all lines by the same fractional amount \(\Delta\lambda/\lambda_0\). If only one line is shifted, it’s not motion — it’s a misidentification.

\[\left[\frac{\Delta\lambda}{\lambda_0}\right] = \frac{\text{nm}}{\text{nm}} = \text{dimensionless} \quad;\quad \left[\frac{v_r}{c}\right] = \frac{\text{km/s}}{\text{km/s}} = \text{dimensionless}\ \checkmark\]

Both sides are dimensionless ratios. The units of \(\Delta\lambda\) and \(\lambda_0\) must match (both nm, or both cm), and \(v_r\) and \(c\) must match (both km/s, or both cm/s).

Problem: A nearby star’s H\(\alpha\) absorption line is observed at \(\lambda_{\text{obs}} = 656.5\ \text{nm}\). The laboratory rest wavelength is \(\lambda_0 = 656.3\ \text{nm}\). Is the star approaching or receding, and at what speed?

Solution:

Step 1 — Determine direction.

Since \(\lambda_{\text{obs}} = 656.5\ \text{nm} > \lambda_0 = 656.3\ \text{nm}\), the line is redshifted. The star is receding.

Step 2 — Calculate the wavelength shift. \[\Delta\lambda = \lambda_{\text{obs}} - \lambda_0 = 656.5\ \text{nm} - 656.3\ \text{nm} = 0.2\ \text{nm}\]

Step 3 — Apply the Doppler formula, solved for \(v_r\). \[v_r = c \times \frac{\Delta\lambda}{\lambda_0}\]

Step 4 — Plug in numbers. \[v_r = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times \frac{0.2\ \text{nm}}{656.3\ \text{nm}}\] \[v_r = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times (3.05 \times 10^{-4}) = 91\ \text{km/s}\]

Unit check: (km/s) × (nm/nm) = km/s \(\checkmark\)

Interpretation: The star recedes at about \(91\ \text{km/s}\) — typical for a star in the galactic disk. A shift of only \(0.2\ \text{nm}\) out of \(656.3\ \text{nm}\) (\(0.03\%\)) translates to nearly \(100\ \text{km/s}\) because light is so fast. Modern spectrographs can detect shifts \(1{,}000\) times smaller than this, measuring velocities down to \({\sim}1\ \text{m/s}\) — precise enough to detect the gravitational tug of an orbiting exoplanet.

Observable → Model → Inference

Observable: Absorption lines in a stellar spectrum appear at slightly different wavelengths than laboratory measurements.

Model: The Doppler effect — motion along the line of sight shifts wavelengths.

Inference: The measured shift gives the radial velocity — the component of the star’s motion directly toward or away from us.

Radial velocities are not just curiosities. If a star is in a binary system — orbiting a companion — its radial velocity oscillates periodically as it moves toward and away from us during its orbit. By measuring how fast and how often the velocity oscillates, we can determine the orbital period and velocity amplitude, which give us the companion’s mass through Kepler’s laws.

This is the main topic of Lecture 4 — and it’s the most direct way we have to measure stellar masses. Spectroscopy doesn’t just tell us what stars are made of; it tells us how much they weigh.

What Doppler Shifts Cannot Tell Us

The Doppler effect measures only the radial component of velocity — motion along the line of sight. A star moving sideways across the sky (transverse velocity, or “proper motion”) doesn’t shift its spectral lines at all. To get the full 3D velocity, we need both Doppler (radial) and astrometric (transverse) measurements — the latter requires tracking the star’s position over years.

Also, if a star is rotating, one limb moves toward you and the other moves away. This doesn’t shift the line center — it broadens the line symmetrically. Line broadening tells us about rotation speed and atmospheric turbulence, but it’s a separate measurement from the Doppler shift of the line center.

- A star’s H\(\beta\) line (rest wavelength \(486.1\ \text{nm}\)) is observed at \(485.9\ \text{nm}\). Is the star approaching or receding?

- Calculate the radial velocity for the star in question 1.

- Can we determine a star’s rotation rate from a single Doppler shift measurement? Why or why not?

- Approaching — \(\lambda_{\text{obs}} < \lambda_0\), so the light is blueshifted.

- \(v_r = c \times \Delta\lambda / \lambda_0 = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times (485.9\ \text{nm} - 486.1\ \text{nm})/486.1\ \text{nm} = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times (-0.2\ \text{nm}/486.1\ \text{nm}) = -123\ \text{km/s}\). The negative sign confirms approach. The speed is \(|v_r| \approx 123\ \text{km/s}\).

- No — rotation broadens spectral lines symmetrically (one limb approaches, the other recedes). We can measure rotational broadening from the width of the line, but a single Doppler shift of the line center tells us only the bulk radial motion.

Doppler Applied: Detecting an Unseen Companion

So far we’ve measured a single Doppler shift — one velocity at one moment. But suppose you observe the same star night after night and find that its radial velocity changes periodically. The H\(\alpha\) line doesn’t just sit at one wavelength — it oscillates back and forth around the rest wavelength on a regular cycle. What could cause that?

If the star has an orbiting companion — another star or a planet — gravitational tugs pull the star toward us during part of the orbit and away during the other part. The result is a periodic Doppler oscillation whose amplitude tells you how fast the star moves and whose period tells you the orbital period.

Problem: You monitor a star over several weeks. Its H\(\alpha\) line (\(\lambda_0 = 656.3\ \text{nm}\)) oscillates between \(656.25\ \text{nm}\) and \(656.35\ \text{nm}\) with a period of \(4.0\ \text{days}\).

(a) What is the velocity amplitude of the star’s wobble?

(b) What does the periodicity tell you about the system?

Solution:

(a) The line oscillates by \(\pm 0.05\ \text{nm}\) around the rest wavelength:

\[\Delta\lambda = \pm 0.05\ \text{nm}\]

Apply the Doppler formula:

\[v_r = c \times \frac{\Delta\lambda}{\lambda_0} = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times \frac{0.05\ \text{nm}}{656.3\ \text{nm}} = \pm 23\ \text{km/s}\]

Unit check: \((\text{km/s}) \times (\text{nm}/\text{nm}) = \text{km/s}\) \(\checkmark\)

The star’s radial velocity oscillates between \(+23\ \text{km/s}\) (receding) and \(-23\ \text{km/s}\) (approaching) — a velocity amplitude of \(23\ \text{km/s}\).

(b) A periodic Doppler oscillation means the star is orbiting something — an unseen companion. The \(4.0\ \text{day}\) period is the orbital period. The companion could be another star (a spectroscopic binary) or a planet. This is exactly how the first exoplanet around a Sun-like star — 51 Pegasi b — was discovered in 1995: its host star wobbled with a velocity amplitude of about \(56\ \text{m/s}\) and a period of \(4.23\ \text{days}\). That wobble is 400 times smaller than our worked example — detecting it required extraordinary spectrograph precision.

Key insight: A single Doppler shift gives one velocity. Repeated Doppler measurements over time reveal orbits — and orbits, through Kepler’s laws, give masses. This is the bridge to Lecture 4.

Part 4 takeaway: The Doppler shift formula \(\Delta\lambda/\lambda_0 = v_r/c\) converts tiny wavelength shifts into stellar velocities. Blueshifts mean approach; redshifts mean recession. This tool unlocks binary star masses in Lecture 4 and, on cosmological scales, reveals the expansion of the universe.

Clue 3: The shifts of line positions — every line offset by the same fractional amount — tell you the star’s radial velocity. Blueshifted lines mean the star approaches; redshifted lines mean it recedes.

Part 5: Putting It Together — Reading a Real Stellar Spectrum

You now have a complete spectroscopic toolkit. Before applying it, take stock of what a single stellar spectrum gives you — three independent pieces of information:

| Observable | What we measure | What we infer |

|---|---|---|

| Which lines appear (wavelength positions) | Line wavelengths matched to lab data | Composition — which elements are present |

| How strong lines are (depth and pattern) | Relative strengths of different species’ lines | Temperature (spectral type) — which quantum states are populated |

| Where lines are shifted (offset from lab wavelengths) | Doppler shift \(\Delta\lambda\) | Radial velocity — motion toward/away from us |

Additional information can be extracted from line widths (broadening from pressure, rotation, turbulence) and line splitting (Zeeman effect from magnetic fields), but the three inferences above are the workhorses.

Open the SDSS SkyServer spectrum viewer. Enter any plate/MJD/fiber combination (try Plate 285, MJD 51930, Fiber 164 for a classic A-star). Look at the spectrum and identify:

- Continuum shape — does it rise toward blue or red?

- Absorption lines — can you spot the Balmer series (H\(\alpha\) at \(656\ \text{nm}\), H\(\beta\) at \(486\ \text{nm}\))?

- Line shifts — are the lines exactly at their rest wavelengths, or slightly offset?

You’ve just done real spectroscopy. Every line you spotted encodes the same physics you learned in Parts 1–4.

Spectra are powerful, but they have limits. Spectroscopy alone does not directly give luminosity (you need distance + photometry), mass (you need binary orbits or asteroseismology), radius (you need Stefan-Boltzmann with \(L\) and \(T\)), distance (you need parallax or standard candles), or transverse velocity (you need astrometric tracking over years).

Each lecture in Module 2 adds one link:

| Lecture | New Tool | What It Unlocks |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Parallax → distance | Distance, then luminosity (\(L = 4\pi d^2 F\)) |

| 2 | Color → temperature; Stefan-Boltzmann | Radius (\(R\) from \(L\) and \(T\)) |

| 3 | Spectral lines → composition, \(T\), \(v_r\) | Chemical inventory; refined temperature; radial velocity |

| 4 | Binary orbits + Doppler | Mass |

| 5–6 | Magnitudes + HR diagram | Full stellar classification |

Combined with distance (Lecture 1) and Stefan-Boltzmann (Lecture 2), we can now characterize five fundamental stellar properties — distance, luminosity, temperature, radius, and composition — from photons alone. Mass requires one more tool: binary orbits (Lecture 4).

All clues collected. From a single stellar spectrum you can now read: composition (which lines), temperature (line-strength pattern), and radial velocity (line shifts). Three independent measurements from one observation — the power of spectroscopy.

Check Yourself

- List three things a stellar spectrum tells you directly.

- List two things a stellar spectrum does not tell you directly.

- How does Lecture 3’s toolkit (spectroscopy) complement Lecture 1’s toolkit (parallax + inverse-square law)?

Now let’s use all three clues simultaneously on a real problem.

Worked Example 3: Diagnosing a Mystery Star

Problem: You observe a star and measure the following:

- Blackbody fit to the continuum gives \(T_{\text{eff}} \approx 9{,}500\ \text{K}\)

- Strong H\(\alpha\), H\(\beta\), H\(\gamma\) absorption lines (hydrogen Balmer series)

- Weak metal lines

- H\(\alpha\) line center observed at \(656.1\ \text{nm}\) (rest wavelength: \(656.3\ \text{nm}\))

What can you infer about this star?

Solution:

(a) Spectral type: The temperature (\({\sim}9{,}500\ \text{K}\)) and strong Balmer lines point to spectral type A — the Goldilocks temperature for hydrogen absorption. Weak metal lines are consistent: at this temperature, metals aren’t prominent.

(b) Radial velocity: \[\Delta\lambda = 656.1 - 656.3 = -0.2\ \text{nm}\]

The line is blueshifted (shorter wavelength), so the star is approaching.

\[v_r = c \times \frac{\Delta\lambda}{\lambda_0} = (3.0 \times 10^5\ \text{km/s}) \times \frac{-0.2\ \text{nm}}{656.3\ \text{nm}} \approx -91\ \text{km/s}\]

The star approaches at about \(91\ \text{km/s}\).

(c) What else would we need? To complete the picture:

- Distance (from parallax) → luminosity from flux + distance

- Luminosity + temperature → radius via Stefan-Boltzmann

- Time-series Doppler measurements → check for binary companion → mass

Interpretation: From a single spectrum, we know this is a hot A-type star made mostly of hydrogen (like all stars), approaching us at \({\sim}91\ \text{km/s}\). The strong Balmer lines and weak metals are exactly what the Boltzmann distribution predicts at \({\sim}9{,}500\ \text{K}\). Spectroscopy confirms and sharpens what color alone suggested.

“O stars have more helium than M stars.” Wrong. Composition is similar across spectral types. O stars show helium lines because the extreme temperature excites helium transitions; M stars don’t because they’re too cool.

“Spectral type tells me composition.” Not directly. Spectral type primarily tells you temperature. Composition requires careful analysis of individual line strengths relative to models.

“Redshift means the star is red.” No. A redshifted star could be blue, white, yellow — any color. “Redshift” means its spectral lines are shifted to longer wavelengths. A blue O star receding from us is still blue — its lines are just \(0.01\%\) longer than in the lab.

“Stronger lines mean more of that element.” Not necessarily. As you learned in Part 3, line strength depends primarily on temperature — which quantum states are populated — not on how much of that element is present. A star with strong hydrogen Balmer lines (spectral type A) doesn’t have more hydrogen than a star with weak Balmer lines (spectral type M). It just has the right temperature to populate the \(n = 2\) level. Abundance matters, but it’s a secondary effect that requires careful modeling to extract.

“Absorption lines make a star dimmer.” Negligibly. When an atom absorbs a photon at a line wavelength, it re-emits a photon in a random direction — this is resonant scattering. Because re-emission goes in all directions (not just toward us), the line appears dark along our line of sight. More precisely, the higher opacity at line wavelengths means the photons we receive at those wavelengths emerge from higher, cooler atmospheric layers, so they carry less intensity. The total luminosity of the star is conserved; the spectrum just has narrow dark features carved into it.

Part 6: Spectroscopy Meets Climate — Why CO\(_2\) Warms Planets

Everything you’ve learned about spectral absorption applies not only to stars but to planetary atmospheres. The same quantum physics that creates stellar absorption lines also creates the greenhouse effect — one of the most consequential applications of spectroscopy in all of science.

Planetary Energy Balance: Stefan-Boltzmann Applied to Planets

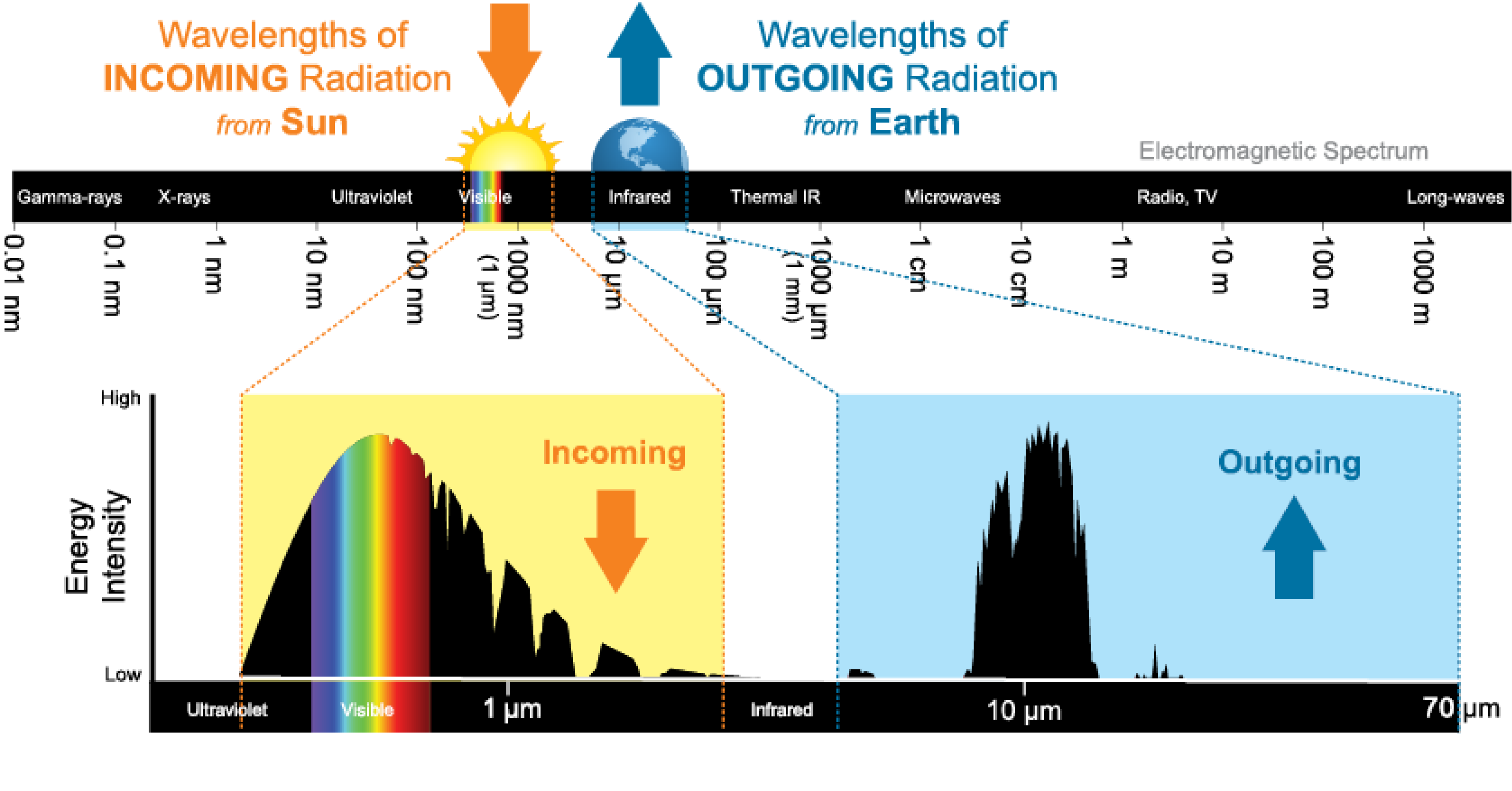

In Lecture 2, you learned the Stefan-Boltzmann law: \(L = 4\pi R^2 \sigma T^4\). That law applies to any blackbody — and to first approximation, a planet is one. A planet doesn’t generate its own luminosity — it absorbs sunlight and re-radiates that energy as thermal (blackbody) radiation at infrared wavelengths. The key insight is that the Sun and Earth are both approximate blackbodies, but at very different temperatures: the Sun’s Planck curve peaks in visible light (~0.5 \(\mu\text{m}\)), while Earth’s peaks in the thermal infrared (~10 \(\mu\text{m}\)). These two blackbody spectra barely overlap — and that spectral separation is what makes the greenhouse effect possible.

At energy balance, the planet radiates exactly as much as it absorbs:

\[\text{Power absorbed from star} = \text{Power radiated by planet}\]

The power absorbed from the star is built from three factors:

- Stellar flux at the planet’s distance: \(L_\star / 4\pi d^2\) — the luminosity spread over a sphere of radius \(d\).

- Intercepted cross-section: \(\pi R_p^2\) — this is the area of the shadow the planet casts, not the planet’s total surface area. Think of how the full Moon looks from Earth: you see a flat disk, not a sphere. Starlight “sees” the planet the same way — as a circular disk of area \(\pi R_p^2\). (The planet’s full surface area is \(4\pi R_p^2\), four times larger, which matters on the re-radiation side.)

- Albedo correction: \((1 - A)\), where the albedo \(A\) is the fraction of incoming light a planet reflects back to space without absorbing it. A perfectly absorbing body has \(A = 0\); a perfect mirror has \(A = 1\). Real solar-system values span a wide range: the Moon’s surface is dark rock (\(A \approx 0.12\)), Earth’s clouds, ice, and oceans give \(A \approx 0.30\), and Venus’s thick sulfuric-acid clouds make it almost mirror-like (\(A \approx 0.75\)). Higher albedo means less energy absorbed and a cooler equilibrium temperature.

Putting these together:

\[\text{Absorbed} = \frac{L_\star}{4\pi d^2} \times \pi R_p^2 \times (1 - A)\]

The power radiated by the planet (modeled as a blackbody radiating isotropically from its full surface — now we use the full \(4\pi R_p^2\), because the planet re-radiates in all directions, not just toward the star) is:

\[\text{Radiated} = 4\pi R_p^2 \sigma T_{\text{eq}}^4\]

Setting these equal and solving for the equilibrium temperature \(T_{\text{eq}}\) — the blackbody temperature the planet would have if it had no atmosphere:

\[T_{\text{eq}} = \left(\frac{L_\star (1-A)}{16\pi\sigma d^2}\right)^{1/4}\]

The general equilibrium-temperature formula contains five quantities — \(L_\star\), \(A\), \(\sigma\), \(d\), and \(T_{\text{eq}}\) — three of which are fundamental constants or stellar properties. The ratio method strategy is: evaluate the messy constants once for a convenient reference case, then express every new problem as dimensionless ratios multiplied by that reference value.

Step 1 — Pick a reference case. Choose a zero-albedo planet orbiting the Sun at 1 AU. Set \(L_\star = L_\odot\), \(A = 0\), \(d = 1\ \text{AU}\):

\[T_{\text{ref}} = \left(\frac{L_\odot}{16\pi\sigma\, (1\ \text{AU})^2}\right)^{1/4}\]

Step 2 — Evaluate \(T_{\text{ref}}\) once and for all. Plug in CGS values:

\[T_{\text{ref}}^{\,4} = \frac{3.828 \times 10^{33}\ \text{erg s}^{-1}}{16\pi\,(5.670 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{erg\,cm}^{-2}\text{s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4})\,(1.496 \times 10^{13}\ \text{cm})^2}\]

Working the denominator: \(16\pi \times 5.670 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{erg\,cm}^{-2}\text{s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4} \times 2.238 \times 10^{26}\ \text{cm}^2 = 6.38 \times 10^{23}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}\), so

\[T_{\text{ref}}^{\,4} = \frac{3.828 \times 10^{33}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}}{6.38 \times 10^{23}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}} = 6.00 \times 10^{9}\ \text{K}^4 \quad\Longrightarrow\quad T_{\text{ref}} = 278\ \text{K}\]

(Rounding to three significant figures: \(T_{\text{ref}} \approx 279\ \text{K}\).)

Step 3 — Write the general formula as ratios. For any planet with albedo \(A\) at distance \(d\) from the Sun, divide the general formula by the reference case. The \(\sigma\) and \(16\pi\) cancel, leaving:

\[\frac{T_{\text{eq}}^{\,4}}{T_{\text{ref}}^{\,4}} = \frac{L_\star}{L_\odot}\,(1 - A)\,\left(\frac{d}{1\ \text{AU}}\right)^{-2}\]

Take the fourth root of both sides:

\[\boxed{T_{\text{eq}} = 279\ \text{K} \times \left(\frac{L_\star}{L_\odot}\right)^{1/4} \times (1-A)^{1/4} \times \left(\frac{d}{1\ \text{AU}}\right)^{-1/2}}\]

Every factor is a dimensionless ratio raised to a simple power. No unit conversions, no \(\sigma\), no powers of ten — just the reference value times knobs you can turn by inspection.

Step 4 — Apply. For Earth orbiting the Sun (\(L_\star/L_\odot = 1\), \(d = 1\ \text{AU}\), \(A \approx 0.3\)):

\[T_{\text{eq}} = 279\ \text{K} \times 1 \times (0.7)^{1/4} \times 1 = 279\ \text{K} \times 0.915 = 255\ \text{K} = -18°\text{C}\]

That’s well below freezing — colder than Earth’s actual average surface temperature of about \(288\ \text{K}\) (\(+15°\text{C}\)). Something is warming Earth by about \(33\ \text{K}\) beyond the bare equilibrium. That something is the greenhouse effect.

Why this works so well: Once you have the reference value memorized (\(279\ \text{K}\)), you can estimate any planet’s equilibrium temperature in your head. Mars at \(1.52\ \text{AU}\) with \(A \approx 0.25\)? \(T_{\text{eq}} \approx 279\ \text{K} \times (0.75)^{1/4} \times (1.52)^{-1/2} \approx 279\ \text{K} \times 0.93 \times 0.81 \approx 210\ \text{K}\). No calculator needed — just ratios and intuition.

The Greenhouse Effect: Absorption Lines in the Atmosphere

Here’s where spectroscopy — and the blackbody model — become essential. Earth’s surface radiates as an approximate blackbody at \(288\ \text{K}\). Wien’s law gives the peak wavelength:

\[\lambda_{\text{peak}} = \frac{b}{T} = \frac{2.898 \times 10^6\ \text{nm·K}}{288\ \text{K}} \approx 10{,}000\ \text{nm} = 10\ \mu\text{m}\]

This is deep in the thermal infrared — far from the visible band where sunlight arrives. The figure below makes this separation vivid: the Sun’s incoming Planck curve (left, peaking at ~0.5 \(\mu\text{m}\)) and Earth’s outgoing Planck curve (right, peaking at ~10 \(\mu\text{m}\)) barely overlap. Earth absorbs energy in the visible and must re-radiate it in the infrared.

What to notice: Two blackbodies, two very different temperatures. The Sun (~5,800 K) radiates a Planck curve peaking in visible light (~0.5 \(\\mu\\text{m}\)). Earth (~288 K) re-radiates a Planck curve peaking in thermal infrared (~10 \(\\mu\\text{m}\)). Greenhouse gases absorb in the infrared window where Earth is trying to radiate — not where the Sun’s energy arrives. The sharp absorption features in the outgoing spectrum are the molecular fingerprints of CO\(_2\), H\(_2\)O, and O\(_3\). (Credit: NOAA JetStream)

For Earth to maintain energy balance, this outgoing infrared radiation must escape to space. But greenhouse gases — CO\(_2\), H\(_2\)O, CH\(_4\), N\(_2\)O, and others — have molecular absorption lines and bands in the infrared, precisely where Earth’s blackbody curve is trying to radiate. Look at the sharp absorption features carved into the outgoing spectrum in the figure — those are the molecular fingerprints of greenhouse gases. These molecules absorb outgoing infrared photons and re-emit them in random directions — some back downward toward the surface. The surface receives extra energy and warms until it radiates enough to compensate.

This is Kirchhoff’s law 3 applied to a planet: the atmosphere is the “cool gas” absorbing from the “hot continuum” (Earth’s surface thermal emission). The physics is identical to stellar absorption lines — the only difference is that the relevant wavelengths are in the infrared rather than the visible.

Stellar absorption lines: cool atmosphere absorbs visible/UV photons from hot photosphere → tells us composition and temperature.

Planetary absorption bands: atmospheric molecules absorb infrared photons from warm surface → traps heat and raises temperature.

The governing physics is the same. Kirchhoff’s laws and quantum energy levels explain both phenomena. Spectroscopy is not just a tool for studying distant stars — it is the fundamental science behind Earth’s habitability.

A Tale of Three Planets

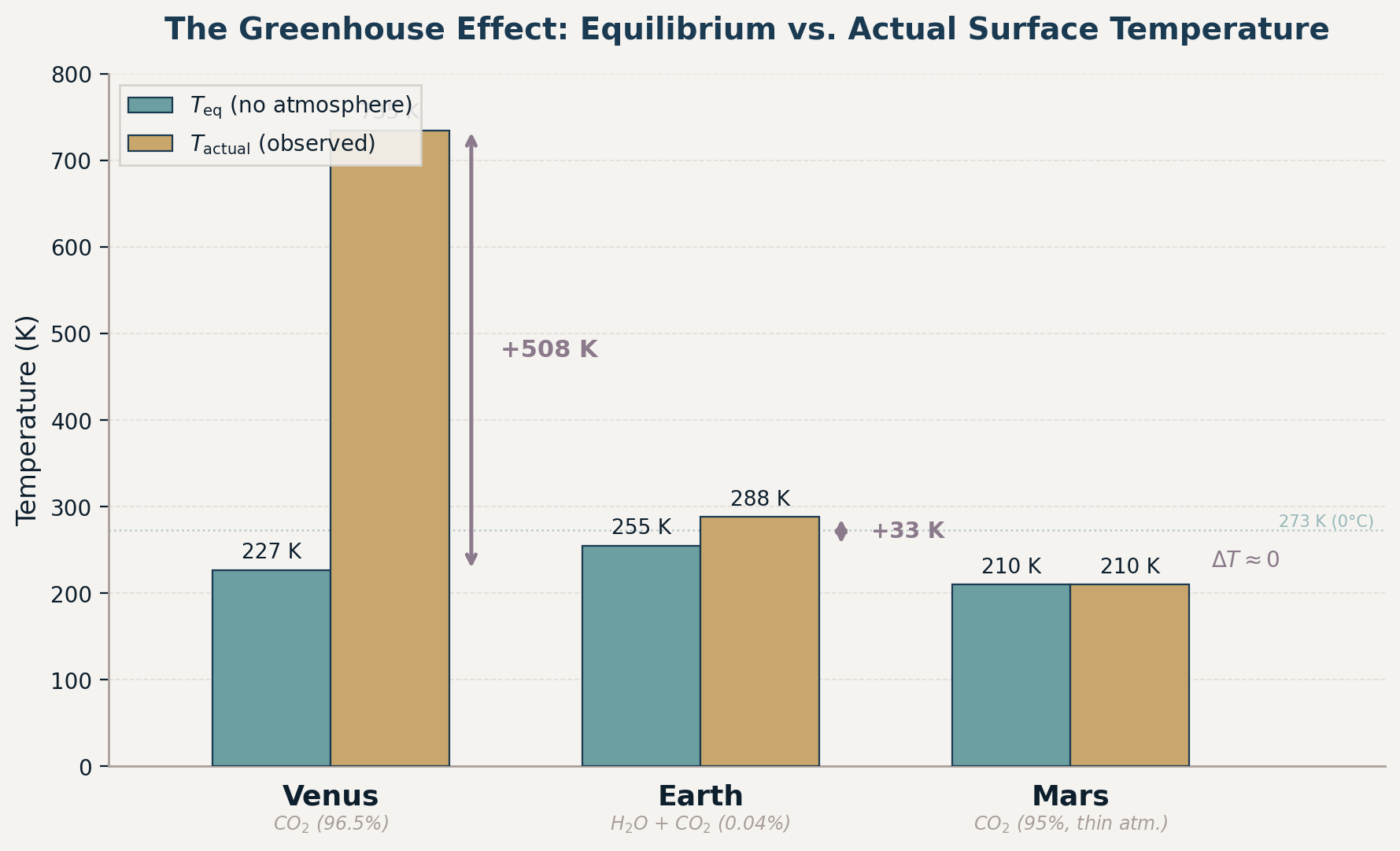

Venus, Earth, and Mars orbit the same star and formed from the same protoplanetary disk — yet their surface temperatures are wildly different. Spectroscopy tells us why:

| Planet | Distance (AU) | Albedo | \(T_{\text{eq}}\) (K) | Actual \(T_{\text{surface}}\) (K) | Greenhouse warming (K) | Dominant greenhouse gas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus | \(0.72\) | \(0.77\) | \(227\) | \(735\) | \(+508\ \text{K}\) | CO\(_2\) (\(96.5\%\) of atmosphere) |

| Earth | \(1.00\) | \(0.30\) | \(255\) | \(288\) | \(+33\ \text{K}\) | H\(_2\)O + CO\(_2\) (\(0.04\%\)) |

| Mars | \(1.52\) | \(0.25\) | \(210\) | \(210\) | \({\sim}0\ \text{K}\) | CO\(_2\) (\(95\%\), but atmosphere very thin) |

What to notice: Venus is closer to the Sun yet has a lower equilibrium temperature than Earth because its high albedo reflects 77% of sunlight. The greenhouse warming (mauve arrows) is what separates \(T_{\\text{eq}}\) from \(T_{\\text{actual}}\) — Venus’s massive CO\(_2\) atmosphere adds 508 K, Earth’s adds 33 K, and Mars’s thin atmosphere adds essentially nothing. (Credit: ASTR 201 (generated))

Look carefully at the table and figure: Venus is closer to the Sun than Earth, yet its equilibrium temperature is lower (\(227\ \text{K}\) vs. \(255\ \text{K}\)). How? Albedo. Venus’s thick sulfuric acid clouds reflect \(77\%\) of incoming sunlight back to space before it can be absorbed. The \((1-A)^{1/4}\) factor in the equilibrium temperature formula means that only the absorbed fraction of sunlight matters. Venus absorbs just \(23\%\) of its incoming flux, while Earth absorbs \(70\%\). The higher albedo more than compensates for the shorter distance — making the \(+508\ \text{K}\) greenhouse warming even more staggering.

Venus is an extreme case: its massive CO\(_2\) atmosphere creates a runaway greenhouse effect — surface temperatures hot enough to melt lead (\(735\ \text{K} = 462°\text{C}\)). Mars has a CO\(_2\)-dominated atmosphere too, but it’s so thin (surface pressure only \(0.6\%\) of Earth’s) that the greenhouse effect is negligible. Earth sits in between — a modest greenhouse effect that makes the planet habitable.

Use the ratio method to verify Mars’s entry in the table above. With \(d = 1.52\ \text{AU}\) and \(A = 0.25\):

\[T_{\text{eq}} = 279\ \text{K} \times (1-0.25)^{1/4} \times \left(\frac{1.52\ \text{AU}}{1\ \text{AU}}\right)^{-1/2}\]

Work through the arithmetic: \((0.75)^{1/4} \approx 0.930\) and \((1.52)^{-1/2} \approx 0.811\). Multiply these together with \(279\ \text{K}\). Do you get close to \(210\ \text{K}\)? What does the fact that \(T_{\text{eq}} \approx T_{\text{surface}}\) tell you about Mars’s atmosphere?

Problem: Calculate Earth’s equilibrium temperature assuming no atmosphere (no greenhouse effect). Use \(L_\odot = 3.828 \times 10^{33}\ \text{erg/s}\), \(d = 1\ \text{AU} = 1.496 \times 10^{13}\ \text{cm}\), and albedo \(A = 0.30\).

Solution:

\[T_{\text{eq}} = \left(\frac{L_\odot (1 - A)}{16\pi\sigma d^2}\right)^{1/4}\]

Step 1 — Compute the numerator. \[L_\odot(1-A) = (3.828 \times 10^{33}\ \text{erg/s}) \times 0.70 = 2.680 \times 10^{33}\ \text{erg/s}\]

Step 2 — Compute the denominator. \[16\pi\sigma d^2 = 16\pi \times (5.67 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{erg\,cm}^{-2}\text{s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}) \times (1.496 \times 10^{13}\ \text{cm})^2\] \[= 16\pi \times (5.67 \times 10^{-5}\ \text{erg\,cm}^{-2}\text{s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}) \times (2.238 \times 10^{26}\ \text{cm}^2)\] \[= 16\pi \times 1.269 \times 10^{22}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}\] \[= 6.376 \times 10^{23}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}\]

Step 3 — Compute \(T_{\text{eq}}^4\). \[T_{\text{eq}}^4 = \frac{2.680 \times 10^{33}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}}{6.376 \times 10^{23}\ \text{erg\,s}^{-1}\text{K}^{-4}} = 4.203 \times 10^9\ \text{K}^4\]

Step 4 — Raise to the \(1/4\) power. \[T_{\text{eq}} = (4.203 \times 10^9\ \text{K}^4)^{1/4}\]

Separate the numerical and unit parts: \((10^9)^{1/4} = 10^{2.25} \approx 177.8\), and \((4.203)^{1/4} \approx (4.203)^{0.5\times0.5} = (2.050)^{0.5} \approx 1.432\), while \((\text{K}^4)^{1/4} = \text{K}\). Combining:

\[T_{\text{eq}} \approx 1.432 \times 177.8\ \text{K} = 255\ \text{K}\]

\[[T_{\text{eq}}] = \left(\frac{[\text{erg/s}]}{[\text{erg cm}^{-2}\ \text{s}^{-1}\ \text{K}^{-4}][\text{cm}^2]}\right)^{1/4} = \left(\text{K}^4\right)^{1/4} = \text{K}\ \checkmark\]

Interpretation: \(255\ \text{K} = -18°\text{C}\). Without an atmosphere, Earth would be a frozen world. The observed average of \(288\ \text{K}\) (\(+15°\text{C}\)) means the greenhouse effect warms Earth by \(33\ \text{K}\) — the difference between a habitable planet and an ice ball. That \(33\ \text{K}\) comes from the infrared absorption bands of water vapor, CO\(_2\), and other trace gases.

Earth’s equilibrium temperature without an atmosphere is \(255\ \text{K}\) — well below freezing. The observed average is \(288\ \text{K}\). What must the atmosphere be doing to account for that \(33\ \text{K}\) difference, and which molecules could be responsible? Think about Kirchhoff’s third law applied to a planet instead of a star.

Why CO\(_2\) Matters: The 15-Micron Band

Carbon dioxide has a particularly strong absorption band centered at \(\lambda \approx 15\ \mu\text{m}\) (\(15{,}000\ \text{nm}\)). This happens to sit right near the peak of Earth’s outgoing thermal radiation. When CO\(_2\) concentration increases, this absorption band deepens and broadens — blocking more outgoing infrared and forcing the surface to warm until the planet radiates enough energy from the remaining transparent wavelength windows.

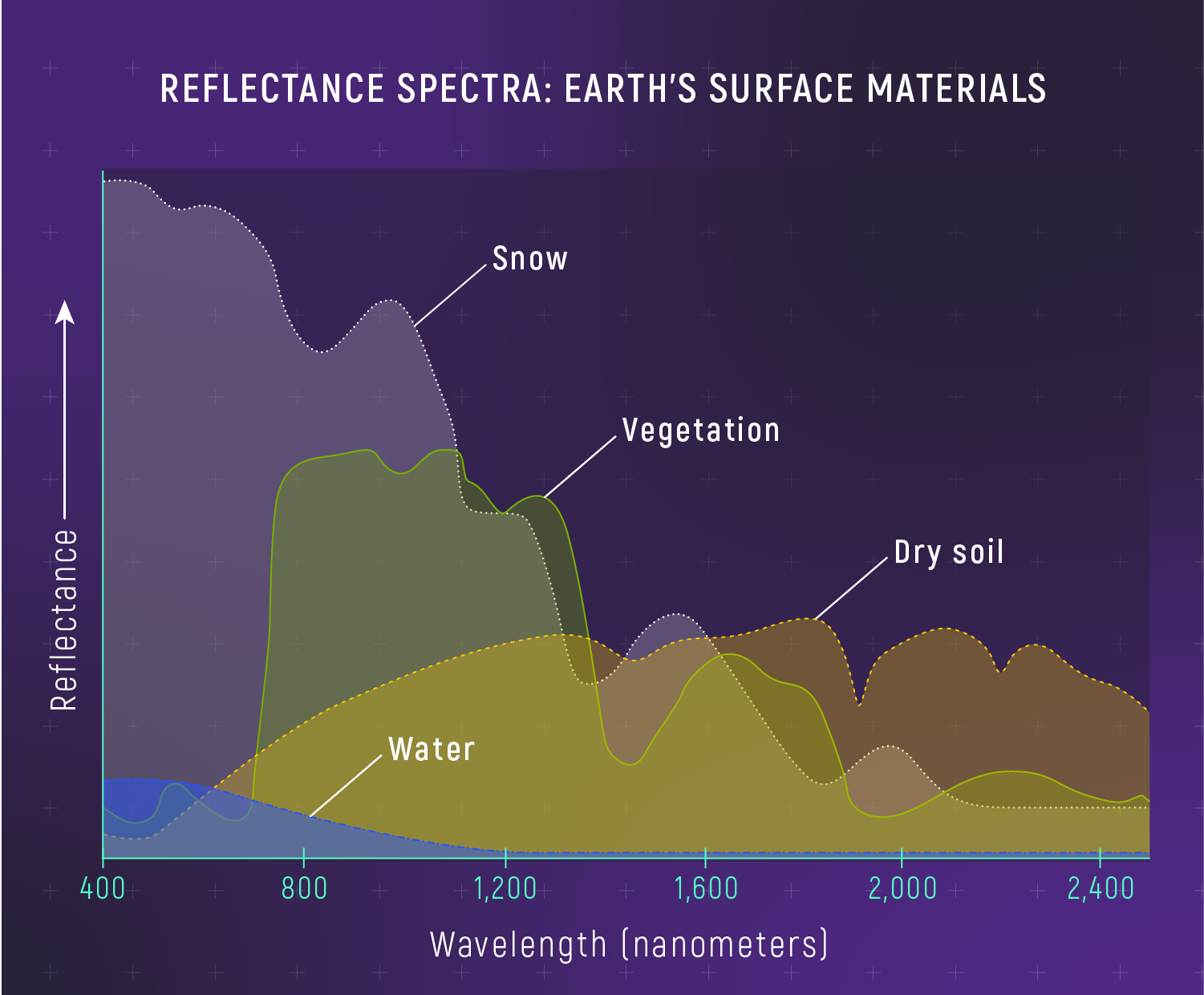

What to notice: Different materials reflect different wavelengths. Snow reflects broadly; water absorbs IR; vegetation has a sharp ‘red edge’ at 700 nm. Spectra can identify surface composition—even on exoplanets. (Credit: JWST/STScI)

The physics is straightforward and has been understood since John Tyndall’s laboratory experiments in 1861 and Svante Arrhenius’s calculations in 1896: CO\(_2\) absorbs infrared radiation at specific wavelengths determined by its molecular energy levels — the same quantum mechanics that produces hydrogen Balmer lines. Adding CO\(_2\) to the atmosphere is, spectroscopically, equivalent to adding more absorbing atoms to a stellar atmosphere — the absorption features deepen.

Earth’s atmosphere is \(78\%\) N\(_2\) and \(21\%\) O\(_2\). Why don’t these dominant gases trap heat?

The answer is spectroscopic. Infrared absorption requires a molecule to change its electric dipole moment when it vibrates — that’s how the molecule couples to the electromagnetic field. The rule is: no change in dipole, no absorption.

N\(_2\) and O\(_2\) are homonuclear diatomic molecules — both atoms are identical. Their only vibrational mode (stretching) doesn’t change the dipole moment because the charge distribution remains symmetric throughout the vibration. They are essentially invisible to infrared radiation.

H\(_2\)O and CH\(_4\) are asymmetric molecules with permanent electric dipole moments. Their vibrations modulate this dipole strongly, making them efficient infrared absorbers.

CO\(_2\) is an interesting intermediate case. It is a symmetric linear molecule (O=C=O) with no permanent dipole moment — in that sense, it’s like N\(_2\). But CO\(_2\) has a bending vibrational mode (the molecule flexes into a V shape) that breaks the symmetry and creates a transient oscillating dipole. This bending mode is what produces the strong 15 \(\mu\text{m}\) absorption band. The asymmetric stretch mode (one C=O bond compresses while the other extends) also changes the dipole and absorbs near 4.3 \(\mu\text{m}\). So CO\(_2\) absorbs IR not because it’s permanently asymmetric, but because some of its vibrations are.

This is why trace gases (CO\(_2\) at only \(0.04\%\) of the atmosphere!) can dominate the greenhouse effect: they interact with infrared light while the dominant gases do not. It’s a beautiful example of quantum selection rules — the same principles that determine which spectral transitions are “allowed” in atoms also determine which molecules can absorb infrared radiation. The universe is consistent.

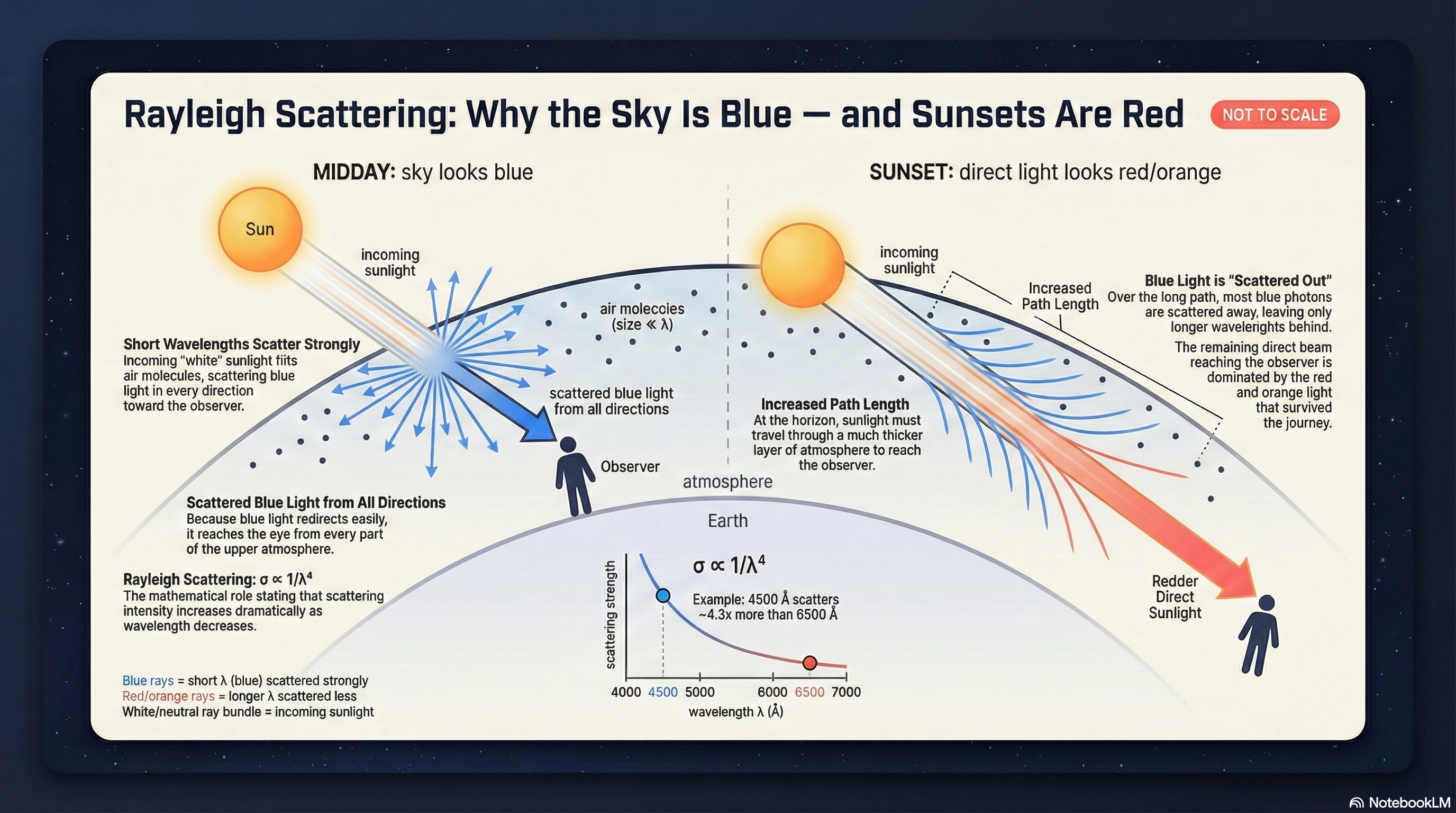

The same physics that governs which molecules absorb infrared radiation also explains something you see every day: the color of the sky.

The scatterers. Earth’s atmosphere is mostly N\(_2\) and O\(_2\) molecules, with sizes around \(\sim 10^{-4}\ \mu\text{m}\) — roughly 5,000 times smaller than visible light wavelengths (\(0.4\)–\(0.7\ \mu\text{m}\)). When a scattering particle is much smaller than the wavelength, we are in the Rayleigh scattering regime, and the scattering cross-section scales as:

\[\sigma_{\text{Rayleigh}} \propto \lambda^{-4}\]

What to notice: Rayleigh scattering explains both the blue sky (scattered short wavelengths) and red sunsets (transmitted long wavelengths). Same physics, different viewing geometry. (Credit: NotebookLM)

That \(\lambda^{-4}\) is steep. Blue light (\(\lambda \approx 450\ \text{nm}\)) scatters about \((650/450)^4 \approx 4.4\) times more efficiently than red light (\(\lambda \approx 650\ \text{nm}\)). Sunlight enters the atmosphere as a roughly continuous spectrum; blue photons scatter out of the direct beam in all directions, filling the entire sky dome with blue light. Red photons, barely deflected, continue straight through. Look at the Sun directly (don’t) and it appears slightly yellow — missing some blue. Look away from the Sun and you see scattered blue light from every direction.

Why sunsets are red. At noon the Sun is overhead and sunlight traverses a relatively short path through the atmosphere. Enough blue light scatters to make the sky blue, but plenty of blue still reaches you directly — the Sun appears white or pale yellow. At sunset the Sun is near the horizon and its light travels through roughly ten times more atmosphere (a longer “column” of air). Over this extended path, most blue photons scatter away before reaching your eye. The surviving photons are overwhelmingly red and orange — hence the deep colors of a sunset.