Tools of the Trade: Math Survival Kit

Lecture 2 Reading Companion

Math isn’t decoration — it’s how we turn points of light into physical understanding.

This page is both (1) the assigned reading and (2) your reference manual for math tools. You should expect to come back to it multiple times — before lecture, after lecture, and while doing practice problems.

Default expectation (best): Read the whole page before class (including Check Yourself). Then return to it later when you work the Practice Problems.

If you’re short on time before class (~15 min): Do the Musts for today so you can participate now — then come back and finish the rest.

- Musts for today: The Big Idea • Scientific Notation basics • Unit Conversions (factor-label method) • The Ratio Method

- Non-negotiable: Stop and answer every Check Yourself question you encounter in these sections (don’t just read past them).

Skim now, read carefully later: Rate Problems, Reference Tables. Skimming is a preview — you’ll get much more from it after lecture.

Reference mode (always): Use the Reference Tables while you work: physical constants, astronomical constants, distance conversions.

Reassurance: This is a toolkit, not a memorization test. You’ll internalize these methods through practice, not cramming.

The Universe Refuses to Be Written in Longhand

If the Sun were a cantaloupe sitting in San Francisco, Earth would be a pinhead 15 meters away. The nearest star? Another cantaloupe in Hawaii.

That’s the scale problem astronomy faces. The numbers are so large (or so small) that ordinary notation fails. Writing out the mass of the Sun — 2,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000,000 kg — is tedious, error-prone, and hides the essential information.

This lecture introduces four tools that professional astronomers use every day:

- Scientific notation & SI prefixes — speak “cosmic scale”

- Unit conversions — translate between measurement systems

- The ratio method — compare without drowning in zeros

- Rate problems — connect distance, time, and speed

These aren’t abstract math exercises. They’re the language physics uses to describe reality.

The Universe’s Phone Number

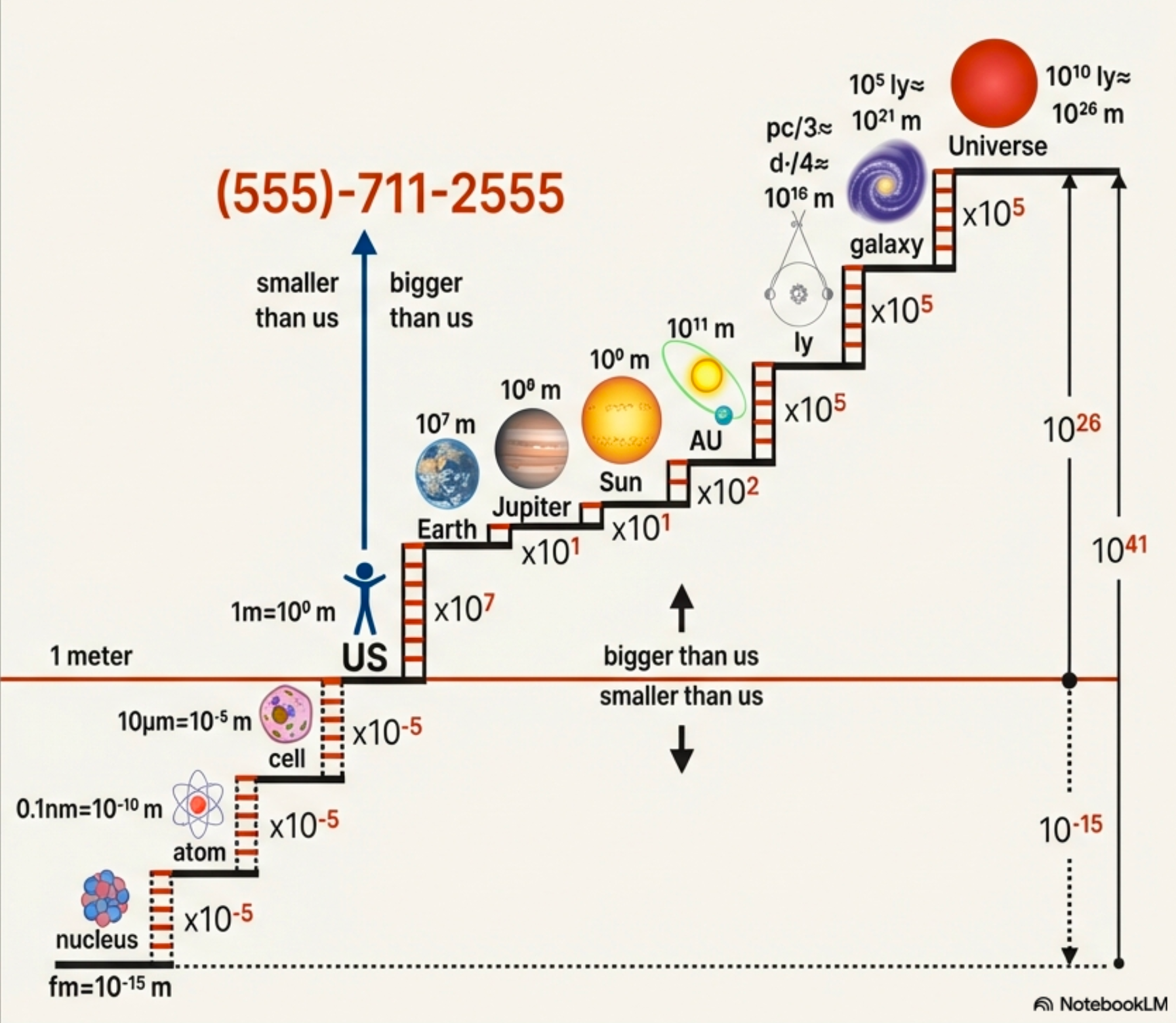

The Universe’s Phone Number: (555)-711-2555 maps cosmic scales (Credit: Adapted from Owocki (course illustration))

The mnemonic: (555)-711-2555 encodes the scale jumps from human to cosmos. Each digit tells you the power of ten between landmarks.

Here’s a mnemonic for navigating cosmic scales, using human scale (~1 m) as the starting point:

Area code (555) — Going small: - First 5: → cells (~\(10^{-5}\) m) - Second 5: → atoms (~\(10^{-10}\) m) - Third 5: → nucleus (~\(10^{-15}\) m)

Exchange (711) — Solar system: - 7: → Earth radius (~\(10^{7}\) m) - 1: → Jupiter radius (~\(10^{8}\) m) - 1: → Sun radius (~\(10^{9}\) m)

Subscriber (2555) — The cosmos: - 2: → Earth-Sun distance, 1 AU (~\(10^{11}\) m) - 5: → nearest stars (~\(10^{16}\) m ≈ 1 parsec) - 5: → Milky Way diameter (~\(10^{21}\) m) - 5: → observable universe (~\(10^{26}\) m)

If your calculation gives a stellar distance of \(10^{9}\) m, the phone number tells you that’s Sun-sized, not star-distance. Immediate red flag!

Light takes about 8.3 minutes to travel 1 AU. How long would it take light to reach something at 2 AU? At 0.5 AU?

Light-travel time scales linearly with distance.

- 2 AU: \(2 \times 8.3\) min = 16.6 minutes

- 0.5 AU: \(0.5 \times 8.3\) min = 4.15 minutes

Tool 1: Scientific Notation & SI Prefixes

Compressing Cosmic Numbers

Scientific notation writes any number as:

\[a \times 10^n\]

where: - \(a\) is the coefficient (usually between 1 and 10) - \(10^n\) is the power of ten - \(n\) is the exponent (tells you the scale)

Examples: - \(300{,}000{,}000\) m/s = \(3.0 \times 10^8\) m/s - \(0.000000001\) s = \(1.0 \times 10^{-9}\) s

Direction rule: - \(n > 0\) → move decimal right (bigger) - \(n < 0\) → move decimal left (smaller)

Operations with Powers of Ten

The algebra of exponents makes cosmic calculations manageable:

| Operation | Rule | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Multiply | Add exponents | \(10^3 \times 10^5 = 10^{8}\) |

| Divide | Subtract exponents | \(10^{33}/10^{27} = 10^{6}\) |

| Powers | Multiply exponents | \((10^3)^2 = 10^{6}\) |

Full example: \((3 \times 10^5)(4 \times 10^3) = (3 \times 4) \times 10^{5+3} = 12 \times 10^8\)

But wait — 12 isn’t between 1 and 10. Normalize by rewriting: \(12 = 1.2 \times 10^1\)

Final answer: \(1.2 \times 10^9\)

SI Prefixes: Naming the Scales

SI prefixes attach to units to indicate powers of ten:

| Prefix | Symbol | Factor | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| tera | T | \(10^{12}\) | THz (far-infrared frequencies) |

| giga | G | \(10^{9}\) | GHz (radio astronomy) |

| mega | M | \(10^{6}\) | Mpc (megaparsec — galaxy distances) |

| kilo | k | \(10^{3}\) | km (planetary scales) |

| \(10^{0}\) | meter, gram, second (human scale) | ||

| milli | m | \(10^{-3}\) | mm (submillimeter astronomy) |

| micro | μ | \(10^{-6}\) | μm (infrared wavelengths) |

| nano | n | \(10^{-9}\) | nm (visible light: 400–700 nm) |

Example: Visible light spans 400–700 nm. The prefix “nano” (\(10^{-9}\)) tells you immediately these are very short wavelengths — about 1000× smaller than a human hair.

What is \((3 \times 10^5)(4 \times 10^3)\) in proper scientific notation?

- Multiply coefficients: \(3 \times 4 = 12\)

- Add exponents: \(10^5 \times 10^3 = 10^{8}\)

- Combine: \(12 \times 10^8\)

- Normalize: \(12 = 1.2 \times 10^1\), so \(12 \times 10^8 = 1.2 \times 10^9\)

Answer: \(1.2 \times 10^9\)

Tool 2: Unit Conversions

Physical Quantities = Number + Unit

A physical quantity is a number attached to a unit. The unit carries meaning.

Physical quantities: - 3 meters - \(5.9 \times 10^{24}\) kg - 300,000 km/s

Not physical quantities: - “3” (three what?) - “really far” - “super hot”

The unit is not optional. Without it, the number is meaningless — like a sentence without a verb.

Physical constant: A number that nature gives us — it doesn’t change. Examples: speed of light \(c\), gravitational constant \(G\).

Conversion Factors = “Multiply by 1”

Since \(1 \text{ m} = 100 \text{ cm}\), we can write:

\[\frac{100 \text{ cm}}{1 \text{ m}} = 1 \quad \text{or} \quad \frac{1 \text{ m}}{100 \text{ cm}} = 1\]

Multiplying by 1 doesn’t change the physical quantity — it only changes the label.

The Factor-Label Method

- Write what you’re given (with units)

- Multiply by conversion factors arranged so units cancel

- Check that final units match what you wanted

Selection rule: Put the unit you want to remove in the denominator.

Example: Convert 60 mph to m/s

\[60 \frac{\text{mile}}{\text{hr}} \times \frac{1.6 \text{ km}}{1 \text{ mile}} \times \frac{1000 \text{ m}}{1 \text{ km}} \times \frac{1 \text{ hr}}{3600 \text{ s}}\]

Watch the units cancel: mile cancels mile, km cancels km, hr cancels hr. What remains is m/s.

\[= \frac{60 \times 1.6 \times 1000}{3600} \frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}} = 26.7 \text{ m/s}\]

Sanity check: 60 mph is highway speed. 27 m/s is about 30 meters per second — roughly 100 feet per second. That feels right for highway driving.

Watch the Exponents!

When a unit is squared or cubed, the conversion factor gets that power too.

The trap: \[1 \text{ km}^3 = 1000 \text{ m}^3\] ❌ WRONG

The right way: \[1 \text{ km}^3 = (1 \text{ km})^3 = (1000 \text{ m})^3 = 1000^3 \text{ m}^3 = 10^9 \text{ m}^3\] ✓

Pro tip: Use parentheses: \((1000 \text{ m})^3\), not \(1000 \text{ m}^3\).

Astronomy’s Distance Units

Astronomers use specialized distance units because cosmic scales span many orders of magnitude:

| Unit | Definition | Value in meters |

|---|---|---|

| AU | Earth-Sun distance | \(1.50 \times 10^{11}\) m |

| light-year (ly) | Distance light travels in one year | \(9.46 \times 10^{15}\) m |

| parsec (pc) | Distance at which 1 AU subtends 1 arcsecond | \(3.09 \times 10^{16}\) m ≈ 3.26 ly |

A light-year is a unit of distance, not time — even though “year” is in the name. It’s how far light travels in one year.

Convert 1 parsec to light-years using the values in the table.

\[1 \text{ pc} = 3.09 \times 10^{16} \text{ m}\] \[1 \text{ ly} = 9.46 \times 10^{15} \text{ m}\]

\[1 \text{ pc} \times \frac{1 \text{ ly}}{9.46 \times 10^{15} \text{ m}} = \frac{3.09 \times 10^{16}}{9.46 \times 10^{15}} \text{ ly}\]

\[= \frac{3.09}{9.46} \times 10^{16-15} \text{ ly} = 0.327 \times 10^1 \text{ ly} = 3.27 \text{ ly}\]

Answer: 1 parsec ≈ 3.26 light-years

Tool 3: The Ratio Method

Escaping the “Big Number” Trap

The mass of the Sun is approximately \(2 \times 10^{30}\) kg. The mass of Earth is roughly \(6 \times 10^{24}\) kg. Subtracting them gives a number that’s still impossibly large to interpret.

But dividing reveals something meaningful:

\[\frac{M_\odot}{M_\oplus} = \frac{2 \times 10^{30}}{6 \times 10^{24}} = \frac{2}{6} \times 10^{30-24} = 0.33 \times 10^6 \approx 330{,}000\]

The Sun is about 330,000 times more massive than Earth. Now we have intuition.

Ratio method: Compare quantities by dividing rather than subtracting. Constants cancel and relative scales become clear.

When comparing two astronomical quantities, which approach gives you more useful insight?

- Subtract them to find the difference

- Divide them to find the ratio

- Add them together

- It doesn’t matter — both give the same information

(b) Divide them to find the ratio. Subtracting cosmic numbers like \(2 \times 10^{30} - 6 \times 10^{24}\) still gives an impossibly large number with no intuitive meaning. But the ratio \(330,000\) tells you immediately that the Sun is 330,000 times more massive than Earth — that’s useful!

The Cancellation Trick

Most astrophysical laws are proportionality relationships. Consider a general power law:

\[A = k B^n\]

where \(k\) is some constant and \(n\) is the scaling power. When we compare two systems:

\[\frac{A_2}{A_1} = \frac{k B_2^n}{k B_1^n} = \left(\frac{B_2}{B_1}\right)^n\]

The constant \(k\) cancels completely! The relative change depends only on the relative input, raised to power \(n\).

Scaling Patterns

The power \(n\) tells the physical story:

| Scaling | Meaning | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| \(\propto R^2\) | Area grows with square | Telescope collecting area, surface area |

| \(\propto R^3\) | Volume grows with cube | Planet volumes, “how many Earths” |

| \(\propto 1/r^2\) | Inverse-square falloff | Brightness, gravity, light intensity |

Small changes in input lead to big changes in output when \(|n| > 1\).

Worked Example: Telescope Collecting Area

Problem: The Keck telescope has a 10-meter diameter mirror. The Hubble Space Telescope has a 2.4-meter diameter mirror. How much more light can Keck collect?

Setup: Light-collecting area scales as \(A \propto D^2\) (area of a circle).

Ratio method: \[\frac{A_\text{Keck}}{A_\text{Hubble}} = \left(\frac{D_\text{Keck}}{D_\text{Hubble}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{10}{2.4}\right)^2 \approx (4.2)^2 \approx 17\]

Answer: Keck collects about 17× more light than Hubble.

Notice: We never calculated actual areas in square meters. The ratio method eliminated that need.

Worked Example: How Many Earths Fit in the Sun?

Problem: The Sun’s radius is about 109× Earth’s radius. How many Earths could fit inside the Sun?

Setup: Volume scales as \(V \propto R^3\).

Ratio method: \[\frac{V_\odot}{V_\oplus} = \left(\frac{R_\odot}{R_\oplus}\right)^3 = (109)^3 \approx 1.3 \times 10^6\]

Answer: About 1.3 million Earths could fit inside the Sun.

The key insight: Radius ratio of 109 becomes volume ratio of 1.3 million. Volume grows fast!

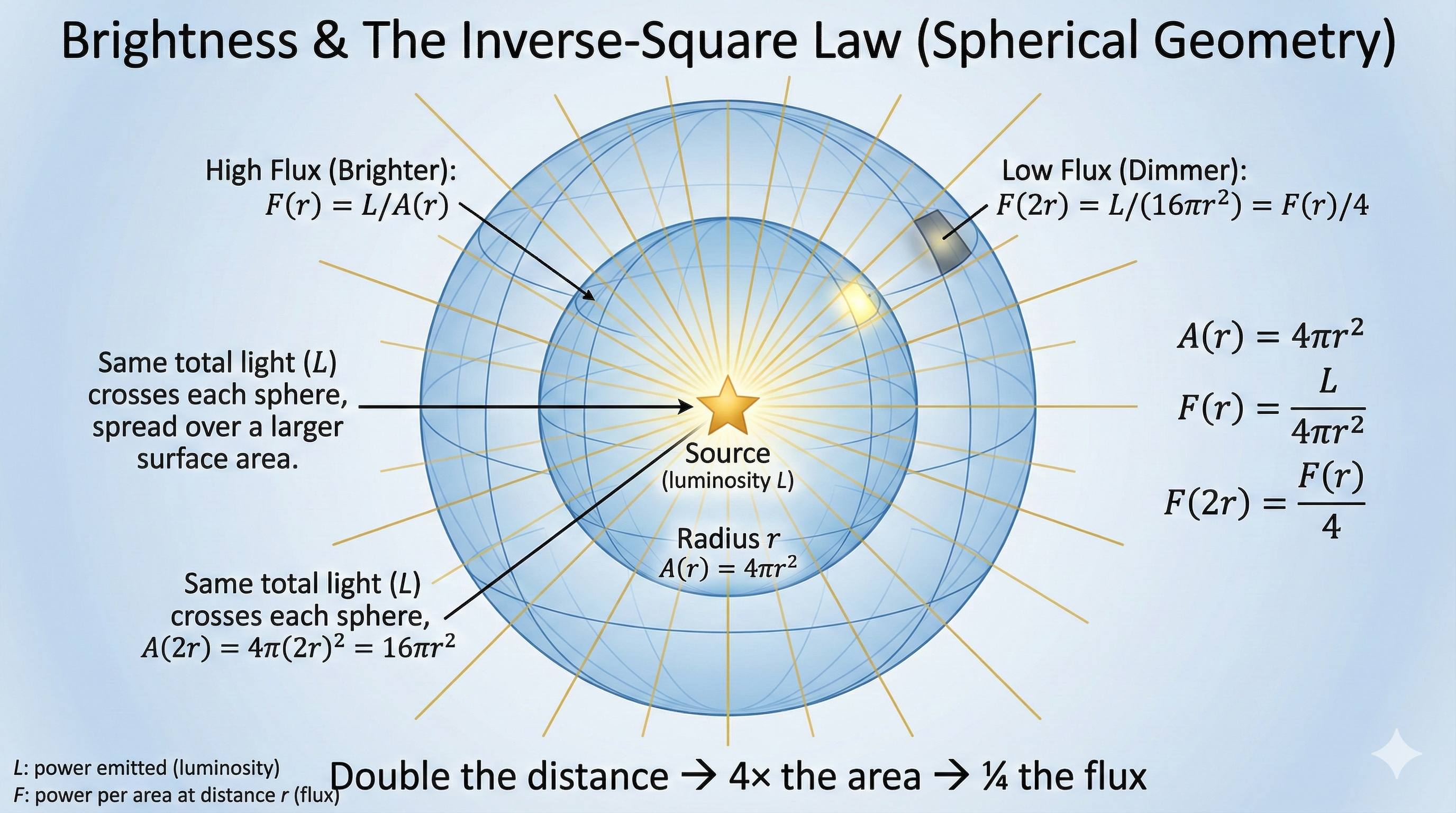

The Inverse-Square Law

Brightness (flux) follows an inverse-square relationship:

\[\text{brightness} \propto \frac{1}{d^2}\]

If you move twice as far from a light source, brightness drops to 1/4 (not 1/2).

Brightness & the Inverse-Square Law: Double the distance → 4× the area → ¼ the flux (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini))

Flux: Energy per second per area reaching your detector (W/m²). Astronomers use flux and brightness interchangeably in this context.

Watch the flip! Because brightness is inversely proportional to \(d^2\), the distance ratio inverts:

\[\frac{B_2}{B_1} = \left(\frac{d_1}{d_2}\right)^2\]

Example: Mars orbits at 1.5 AU. How does sunlight intensity on Mars compare to Earth?

\[\frac{I_\text{Mars}}{I_\text{Earth}} = \left(\frac{d_\text{Earth}}{d_\text{Mars}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{1}{1.5}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{2}{3}\right)^2 = \frac{4}{9} \approx 0.44\]

Mars receives only 44% as much sunlight as Earth.

The Sun’s radius is about 109× Earth’s radius. Using \(V \propto R^3\), what is \(V_\odot / V_\oplus\)?

\((109)^3 \approx 1.3 \times 10^6\). The Sun’s volume is about 1.3 million times Earth’s volume.

Tool 4: Rate Problems & Dimensional Reasoning

The Rate Template

Most rate problems follow one equation with three rearrangements:

\[\text{amount} = \text{rate} \times \text{time}\]

| Find | Formula | Question it answers |

|---|---|---|

| Rate | \(\text{rate} = \frac{\text{amount}}{\text{time}}\) | “How fast?” |

| Time | \(\text{time} = \frac{\text{amount}}{\text{rate}}\) | “How long?” |

| Amount | \(\text{amount} = \text{rate} \times \text{time}\) | “How much/far?” |

Astronomy examples: - Distance = speed × time - Energy = power × time - Mass loss = rate × time

Worked Example: Building a Light-Year

Problem: How far does light travel in one year?

Step 1: Identify the rate equation \[\text{distance} = \text{speed} \times \text{time}\]

Step 2: Gather values - Speed of light: \(c = 3 \times 10^8\) m/s - Time: 1 year

But the units don’t match! We need time in seconds.

Step 3: Convert 1 year to seconds \[1 \text{ yr} \times \frac{365 \text{ days}}{1 \text{ yr}} \times \frac{24 \text{ hr}}{1 \text{ day}} \times \frac{3600 \text{ s}}{1 \text{ hr}} \approx 3.15 \times 10^7 \text{ s}\]

Step 4: Calculate \[d = c \times t = (3 \times 10^8 \text{ m/s})(3.15 \times 10^7 \text{ s})\]

Multiply coefficients, add exponents: \[d = (3 \times 3.15) \times 10^{8+7} \text{ m} = 9.45 \times 10^{15} \text{ m}\]

Answer: 1 light-year ≈ \(9.5 \times 10^{15}\) m (about 9.5 trillion kilometers).

Unit check: \(\frac{\text{m}}{\text{s}} \times \text{s} = \text{m}\) ✓

Dimensional Analysis as “Smoke Detector”

Every equation in physics must be dimensionally consistent. If the dimensions on both sides don’t match, the physics is guaranteed to be wrong — no calculation needed.

The three fundamental dimensions:

| Dimension | Symbol | What it represents |

|---|---|---|

| Length | \([L]\) | Spatial extent |

| Mass | \([M]\) | Amount of matter |

| Time | \([T]\) | Duration |

Example: Checking velocity

Velocity has dimensions \([L]/[T]\) (length per time). If an equation claims:

\[v = \frac{d}{t^2}\]

Check the dimensions: \(\frac{[L]}{[T]^2} = [L T^{-2}]\)

That’s acceleration, not velocity! The equation is dimensionally wrong — don’t bother calculating.

The smoke detector principle: Before plugging in numbers, check that dimensions match your target. Wrong dimensions = guaranteed wrong physics.

Earth moves around the Sun at about 29.8 km/s. How far does Earth travel in one minute?

- Speed: \(v = 29.8\) km/s \(= 2.98 \times 10^4\) m/s

- Time: \(t = 60\) s

\[d = v \times t = (2.98 \times 10^4 \text{ m/s})(60 \text{ s}) = 1.79 \times 10^6 \text{ m}\]

Answer: About 1,800 km in one minute. Earth covers almost 2000 km every minute — cosmic speeds are fast!

Putting It Together

The Problem-Solving Checklist

For any quantitative astronomy problem:

- What am I finding? Write the target with units

- What am I given? Write givens with units

- Pick the tool: Conversion, ratio, or rate

- Do the calculation: Make sure units cancel correctly

- Sanity check: Right power of ten? Right direction (bigger/smaller)?

Recognition, Not Retention

You don’t need to memorize formulas. You need to recognize patterns:

- Powers of ten compress cosmic scales

- Ratios reveal relationships without messy constants

- Units keep your equations honest

- Rates connect distance, time, and speed

When you see a big number or a scaling question, you’ll know which tool to reach for.

Next time: We’ll apply these tools to our first real inference problem — measuring the distance to stars we can never visit.

Coming soon: The cosmic distance ladder, parallax, and standard candles. The math toolkit you just learned makes it all possible.

Reference Tables

Key Physical Constants (SI)

| Constant | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Speed of light | \(c\) | \(3.00 \times 10^8\) m/s |

| Gravitational constant | \(G\) | \(6.67 \times 10^{-11}\) m³/(kg·s²) |

| Stefan-Boltzmann constant | \(\sigma\) | \(5.67 \times 10^{-8}\) W/(m²·K⁴) |

Astronomical Constants (SI)

| Quantity | Symbol | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Solar mass | \(M_\odot\) | \(2.0 \times 10^{30}\) kg |

| Solar radius | \(R_\odot\) | \(7.0 \times 10^{8}\) m |

| Solar luminosity | \(L_\odot\) | \(3.8 \times 10^{26}\) W |

| Astronomical unit | AU | \(1.50 \times 10^{11}\) m |

| Parsec | pc | \(3.09 \times 10^{16}\) m |

| Light-year | ly | \(9.46 \times 10^{15}\) m |

Distance Unit Conversions

| Conversion | Value |

|---|---|

| 1 AU | \(1.50 \times 10^{11}\) m |

| 1 ly | \(9.46 \times 10^{15}\) m |

| 1 pc | \(3.09 \times 10^{16}\) m ≈ 3.26 ly |

| 1 pc | \(2.06 \times 10^{5}\) AU |

Practice Problems

Scientific Notation & Prefixes

1. Express in scientific notation:

- 4,500,000,000 years (age of the solar system)

- 0.00000000656 m (wavelength of H-alpha)

2. Calculate (express answer in proper scientific notation):

- \((2 \times 10^{30})(3 \times 10^8)\)

- \(\frac{9 \times 10^{15}}{3 \times 10^7}\)

- \((4 \times 10^3)^2\)

3. SI Prefixes. A radio telescope observes at a frequency of 1.4 GHz. Express this frequency in Hz using scientific notation.

Unit Conversions

4. Speed of light. Convert the speed of light from m/s to km/hr.

- \(c = 3 \times 10^8\) m/s

5. Wavelength conversion. Red light has a wavelength of 700 nm. Express this in:

- meters

- micrometers (μm)

6. Distance to Proxima Centauri. Proxima Centauri is 4.2 light-years away.

- Convert this to parsecs

- Convert this to meters

Ratio Method

7. Telescope comparison. A new telescope has a mirror diameter of 30 meters. The Hubble Space Telescope has a diameter of 2.4 meters. How much more light can the new telescope collect?

8. Planet volumes. Jupiter’s radius is about 11× Earth’s radius. How many Earths could fit inside Jupiter?

9. Inverse-square brightness. Two identical stars are observed. Star X appears 16× fainter than Star Y. How many times farther away is Star X?

Rate Problems

10. Light travel time. How long does light take to travel from the Sun to Neptune, which orbits at about 30 AU? Give your answer in hours.

11. Earth’s orbital speed. Earth orbits the Sun at about 30 km/s. How far does Earth travel in one day? Express your answer in AU.

12. Signal delay. The Mars rover is 1.5 AU from Earth. How long does a radio signal take to reach the rover? (Radio waves travel at the speed of light.)

Synthesis & Conceptual

13. Putting it together. The star Betelgeuse is about 700 light-years away. A supernova occurred there in the year 1300 CE.

- When will we see it on Earth?

- If we observe the supernova, what is the lookback time?

14. Dimensional check. A student writes the equation \(v = d \cdot t\) for velocity. Is this dimensionally correct? Explain using \([L]\), \([M]\), \([T]\) notation.

15. Why Ratios? The Sun’s mass is \(2 \times 10^{30}\) kg and Earth’s mass is \(6 \times 10^{24}\) kg. Why is calculating the ratio of these masses more useful than calculating their difference? What does the ratio tell you that the difference doesn’t?

16. Sanity Check. A student calculates the distance to a nearby star and gets \(10^9\) m. Using the “Universe’s Phone Number” from this reading, explain why this answer must be wrong. What order of magnitude should a stellar distance be?

Glossary

No glossary terms for lecture 2.