Our Cosmic Backyard — Solar System Architecture & Formation

Lecture 11 Reading Companion

We can measure worlds we will never stand on — masses from orbits, temperatures from infrared glow, compositions from spectral fingerprints. The solar system is where we apply every tool from Module 1. Understanding how it formed explains why rocky planets huddle close to the Sun while gas giants rule the outer reaches.

This reading tours the solar system while reinforcing Module 1 concepts. Think of it as a capstone: we’re applying Kepler, Newton, blackbody, and spectroscopy to our cosmic neighborhood.

Structure:

- Part 1: Solar system architecture — what’s out there?

- Part 2: Applying our toolkit — how do we know what we know?

- Part 3: Formation — why does it look this way?

Reading time: ~25-30 min

Exam connection: This week (L11-L13) is designed to reinforce all Module 1 concepts before the exam. Pay attention to how prior tools get applied!

What’s next: L12 compares planetary climates (Venus vs. Earth vs. Mars) and covers exoplanet detection. L13 tackles the big question: Are we alone?

If you only remember three things:

Architecture: Rocky planets inside (~0.4-1.5 AU), gas giants in the middle (~5-10 AU), ice giants farther out (~19-30 AU), icy debris beyond (Kuiper Belt, Oort Cloud).

We know all this remotely: Masses from moon orbits (Newton), temperatures from infrared (Wien), compositions from spectra (L9). Same toolkit as stars!

Formation explains the pattern: The frost line (~3 AU) separated where ices could form from where they couldn’t. More solid material beyond the frost line → bigger cores → gas giants.

Now for the details…

In L10, we finished building your toolkit: Kepler, Newton, blackbody, spectroscopy, Doppler, telescopes. Now we need something to point that toolkit at.

The solar system is the perfect target. It’s close enough that we have ground truth (spacecraft have visited every planet). It’s diverse enough to test every tool. And its architecture tells a story about how planetary systems form — knowledge we’ll need when we hunt for exoplanets in L12.

Think of L11–L13 as the final exam prep you didn’t know you wanted: applying everything in context.

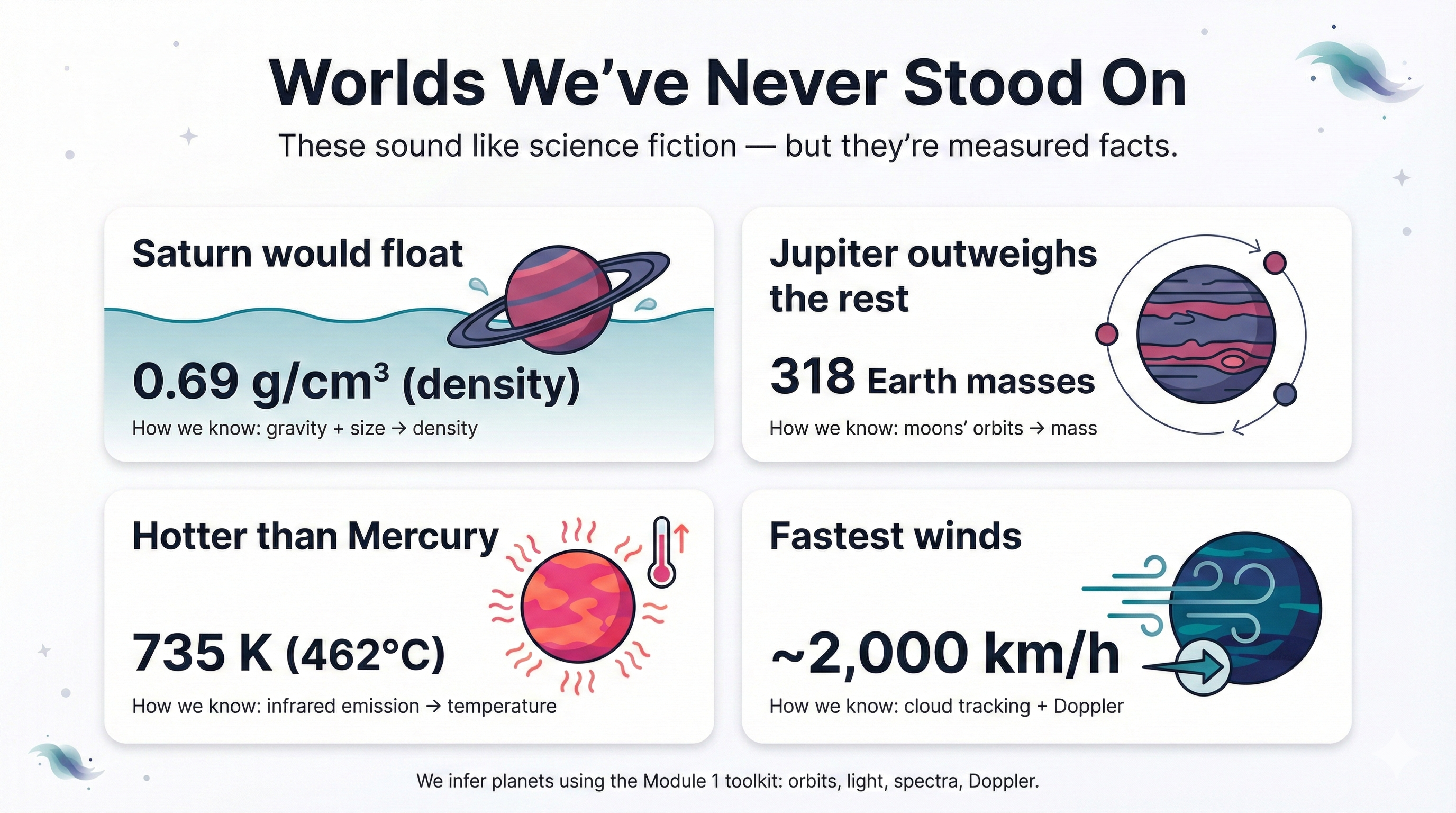

Worlds We’ve Never Stood On

We know the mass of Jupiter — and we didn’t learn it by “weighing” a planet. We learned it by watching how other things move around it.

That’s the superpower of astronomy: we can measure worlds we will never stand on. A planet’s mass from orbits. Its temperature from infrared glow. Its composition from spectral fingerprints. All from billions of kilometers away.

Here are facts that sound like science fiction but aren’t:

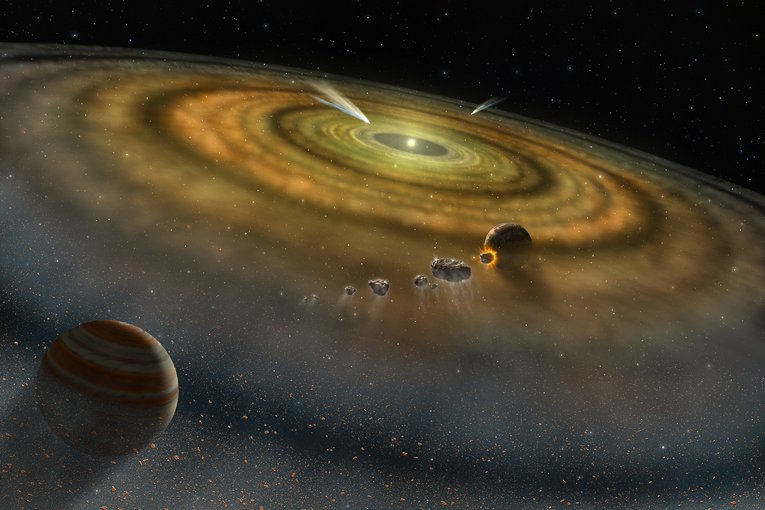

What to notice: we can infer basic planet properties (mass, density, temperature, winds) without visiting — by combining orbits, light, spectra, and Doppler. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — illustrative))

Saturn would float in water — its density is about 0.69 g/cm³, less than water’s 1.0 g/cm³.

Jupiter outweighs all the other planets combined — about 318 Earth masses.

Venus is hotter than Mercury, even though it’s farther from the Sun — about 460°C at the surface, hot enough to melt lead.

Neptune has the fastest winds in the solar system — roughly 2,000 km/h, several times faster than the strongest hurricanes on Earth.

How do we know these are true? That’s what this lecture is about.

Over the past weeks, you’ve assembled a powerful toolkit: Kepler’s Laws describe orbits. Newton’s gravity reveals mass. Blackbody radiation encodes temperature. Spectral lines fingerprint composition. The Doppler effect measures motion.

Now we apply these tools to our own solar system — the best practice ground we have.

Take 2 minutes to answer these from memory (no peeking!):

- Kepler’s Third Law relates which two quantities?

- Doppler effect measures which component of velocity — radial or transverse?

- Wien’s Law lets you infer what property from a spectrum?

If you struggled, review the relevant lecture before continuing. This reading assumes you have these tools ready to apply.

- Period and semi-major axis (\(P^2 \propto a^3\))

- Radial (line-of-sight)

- Temperature from peak wavelength

| Tool | From Lecture | Solar System Application |

|---|---|---|

| Kepler’s Laws | L5 | Orbital distances, periods, predicting positions |

| Newton’s Gravity | L6 | Planetary and moon masses from orbits |

| EM Spectrum | L7 | Observing planets at IR, radio, UV |

| Blackbody/Wien | L8 | Surface and atmospheric temperatures |

| Spectroscopy | L9 | Atmospheric compositions |

| Doppler Effect | L10 | Rotation rates, wind speeds |

This week: We apply ALL of these to planets, climate, exoplanets, and the search for life.

Part 1: Solar System Architecture

The Grand Tour

Our solar system has a clear structure, organized by distance from the Sun. Let’s take a tour from the scorching inner regions to the frozen outer reaches.

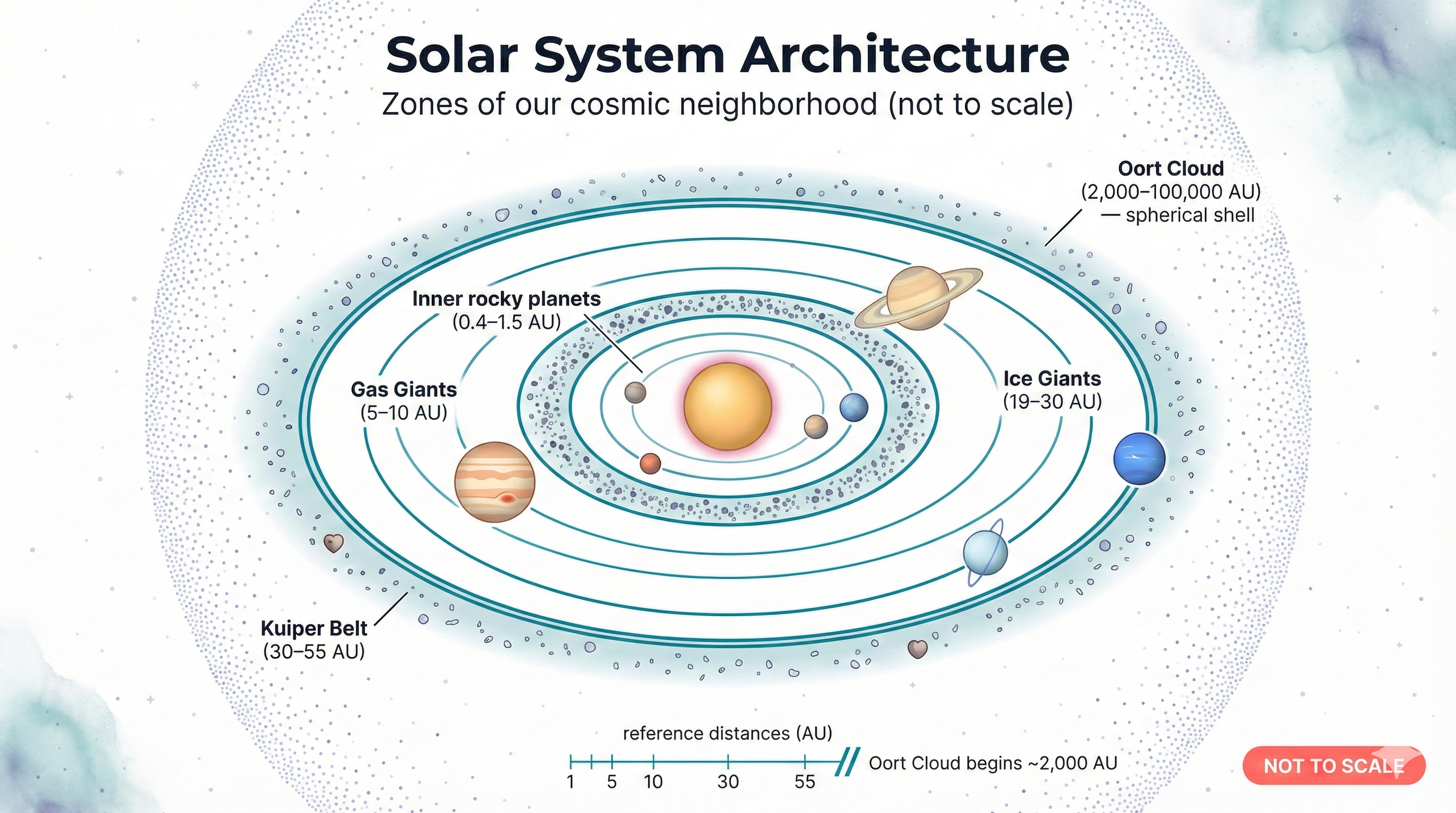

What to notice: the solar system is structured in zones (not to scale) — rocky planets inside, giant planets farther out, then icy small-body reservoirs (Kuiper Belt, Oort Cloud). (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — illustrative))

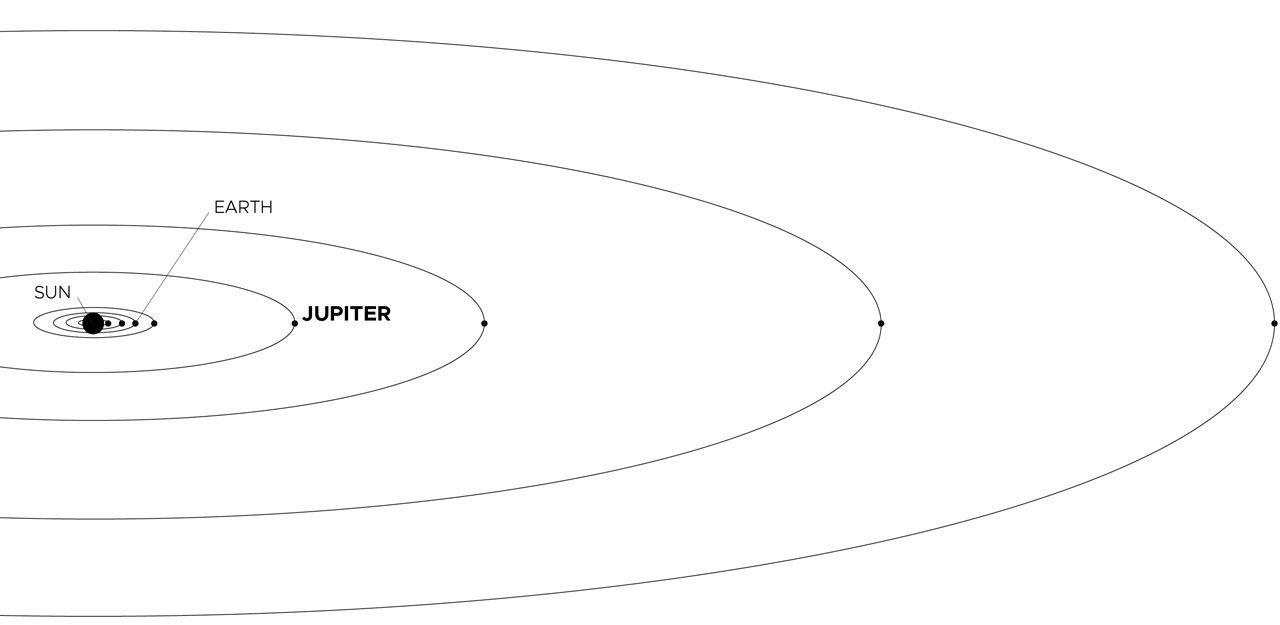

What to notice: Distances in the solar system are easiest to compare in AU — the inner planets are packed close together compared to the giant-planet region. (Credit: NASA)

The Zones

Think of the solar system as organized into distinct zones, each with characteristic objects:

The Inner Solar System (0.4–1.5 AU): This is the realm of the rocky planets — Mercury, Venus, Earth, and Mars. These worlds are small, dense, and have solid surfaces you could (in principle) stand on. They’re close enough to the Sun that temperatures would have been too high for ices to form when the solar system was young.

The Asteroid Belt (2–4 AU): Between Mars and Jupiter lies a ring of millions of rocky and metallic bodies — the asteroids. These are planetesimals that never accreted into a planet. Jupiter’s gravitational influence (especially through orbital resonances) kept collisions destructive rather than constructive, preventing a fifth rocky planet from forming.

The Gas Giants (5–10 AU): Jupiter and Saturn dominate this region. These massive worlds are composed primarily of hydrogen and helium — the same elements that make up the Sun. They have no solid surface; if you tried to land, you’d sink through increasingly dense gas until pressure and temperature crushed you. Jupiter alone contains more mass than all other planets combined.

The Ice Giants (19–30 AU): Uranus and Neptune are often grouped with Jupiter and Saturn as “giant planets,” but they’re fundamentally different. They’re smaller, and instead of being hydrogen-dominated, they contain substantial amounts of water, ammonia, and methane ices. Their blue-green colors come from methane absorbing red light.

The Kuiper Belt (30–55 AU): Beyond Neptune lies a disk of icy bodies left over from the solar system’s formation. Pluto lives here, along with other dwarf planets like Makemake and Haumea. The Kuiper Belt is the source of many short-period comets. Scattered disk objects (like Eris) occupy even more eccentric and inclined orbits beyond the classical Kuiper Belt.

The Oort Cloud (~2,000–100,000 AU): At the outer edges of the Sun’s gravitational influence lies a vast spherical shell of icy bodies. The inner Oort Cloud extends from roughly 2,000-5,000 AU; the outer cloud reaches from ~10,000 to perhaps 100,000 AU. Objects here are so loosely bound that passing stars and the Milky Way’s gravity can nudge them into the inner solar system as long-period comets.

Astronomical Unit (AU): The average Earth-Sun distance, ~150 million km. A convenient unit for solar system distances.

The Key Pattern

Notice something striking: rocky planets are close to the Sun; gas giants are far away. This isn’t random — it’s a direct consequence of how the solar system formed. We’ll explain why in Part 3.

| Zone | Distance | Objects | Key Properties |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rocky planets | 0.4–1.5 AU | Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars | Small, dense, solid surfaces |

| Asteroid belt | 2–4 AU | Millions of rocky/metallic bodies | Planetesimals that never formed a planet |

| Gas giants | 5–10 AU | Jupiter, Saturn | Massive, H/He dominated, no solid surface |

| Ice giants | 19–30 AU | Uranus, Neptune | Smaller, more ices (water, ammonia, methane) |

| Kuiper Belt | 30–55 AU | Pluto, dwarf planets, icy bodies | Source of short-period comets |

| Oort Cloud | ~2,000–100,000 AU | Long-period comets | Spherical halo, barely bound to Sun |

Rocky vs. Giant Planets: Two Families

The planets divide neatly into two families with dramatically different properties:

| Property | Rocky (Terrestrial) | Giants |

|---|---|---|

| Size | Small (0.4–1 R⊕) | Large (4–11 R⊕) |

| Mass | Low (0.06–1 M⊕) | High (15–318 M⊕) |

| Density | High (4–5 g/cm³) | Low (0.7–1.6 g/cm³) |

| Composition | Rock, metal | H, He, ices |

| Surface | Solid | None (gas/liquid) |

| Moons | Few (0–2) | Many (dozens) |

| Rings | None | Yes |

The density difference is particularly striking. Earth’s density is 5.5 g/cm³ — about five times denser than water. Saturn’s density is just 0.69 g/cm³ — less than water. If you could find an ocean big enough, Saturn would float!

Students learn patterns faster through paired comparisons. As you read, think about these contrasts:

Mercury vs. Venus: Both inner planets, but Mercury has no atmosphere (extreme temperature swings: 430°C day, -180°C night) while Venus has a thick atmosphere (constant 460°C everywhere). Same region, different fates.

Venus vs. Earth: Nearly the same size, but Venus receives ~2× Earth’s sunlight (0.72 AU vs. 1.0 AU) and is 450°C hotter. Why so extreme? (Answer in L12: runaway greenhouse effect.)

Jupiter vs. Saturn: Both gas giants with similar composition, but Saturn’s density (0.69 g/cm³) is lower than water’s. Why? Saturn is less massive, so less compressed.

These comparisons reveal what physics is doing.

Saturn has a density of 0.69 g/cm³ — less than water. What does this tell you about its composition?

- It must be made of rock and metal

- It must be made primarily of lightweight gases (hydrogen, helium)

- It has no atmosphere

- It’s the same composition as Earth

B) It must be made primarily of lightweight gases (hydrogen, helium). Rocky planets have densities of 4-5 g/cm³. Saturn’s low density tells us it’s dominated by hydrogen and helium, the lightest elements. If you could find a big enough ocean, Saturn would float!

A Quick Photo Tour (One World at a Time)

Pictures help your intuition. As you read the rest of this lecture, keep asking the same question: What does this world look like, and what physics makes it that way?

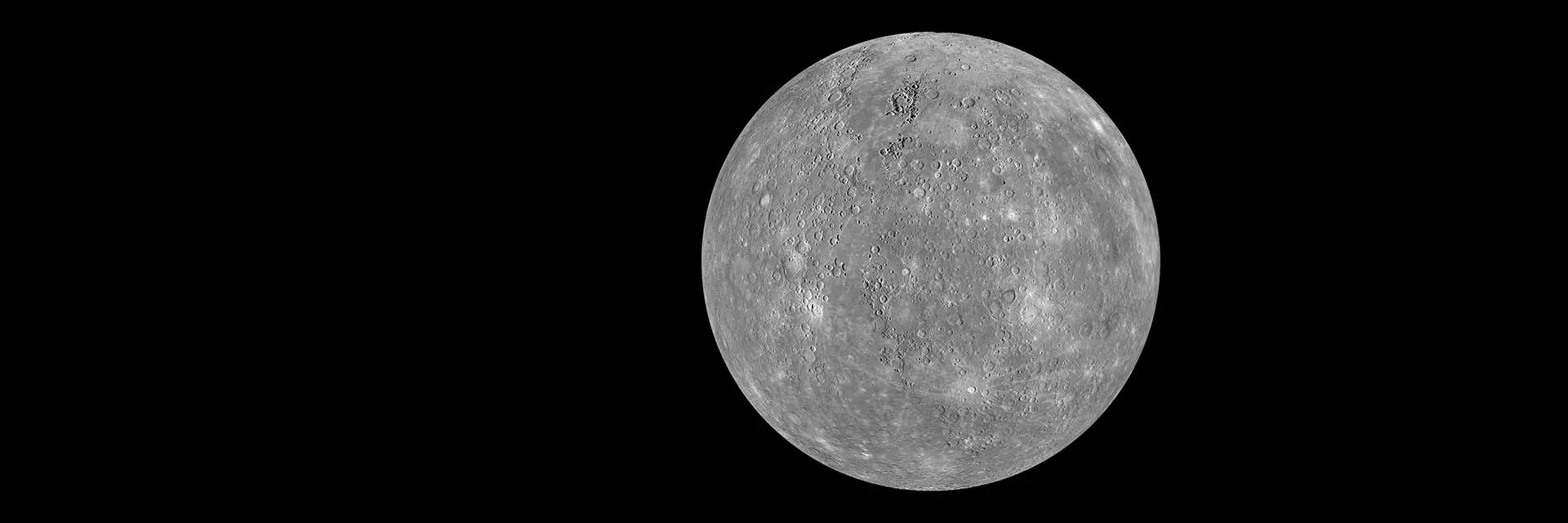

Rocky planets: solid surfaces, big contrasts

Mercury is the endmember for “no atmosphere.” Its surface is a cratered record of early impacts, and its temperature swings are extreme because there’s essentially no air to move heat around.

What to notice: Mercury’s surface is heavily cratered and airless — a record of early impacts with little erosion. (Credit: NASA)

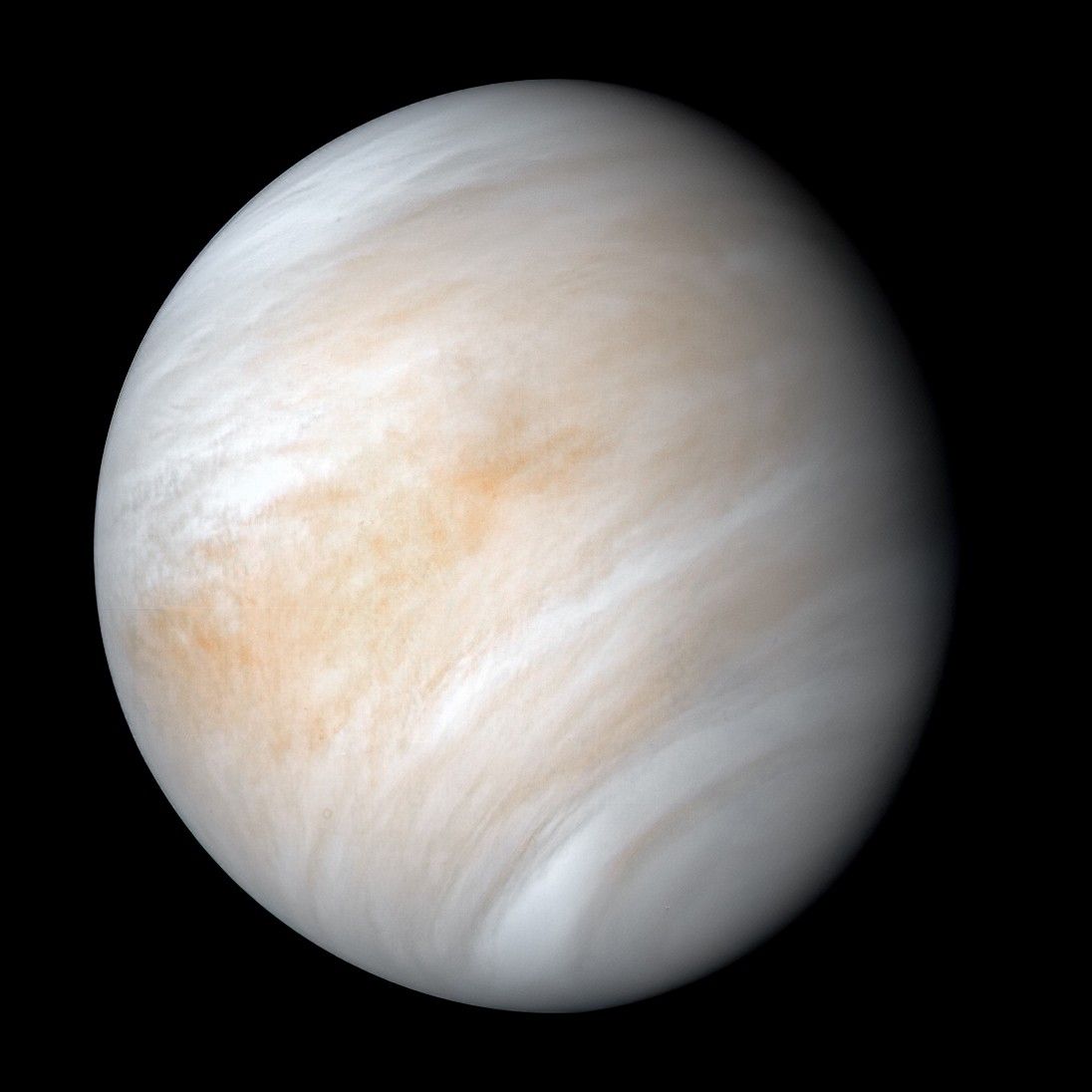

Venus is the opposite: in visible light we don’t see a rocky surface at all, just a bright, global cloud deck. The climate physics lives in the atmosphere.

What to notice: Venus is completely cloud-covered in visible light — we do not see the surface directly without using other wavelengths or radar. (Credit: NASA)

Earth is our control case — oceans, clouds, and an atmosphere thick enough to matter.

What to notice: Earth’s oceans and atmosphere matter — they shape temperature, weather, and habitability. (Credit: NASA)

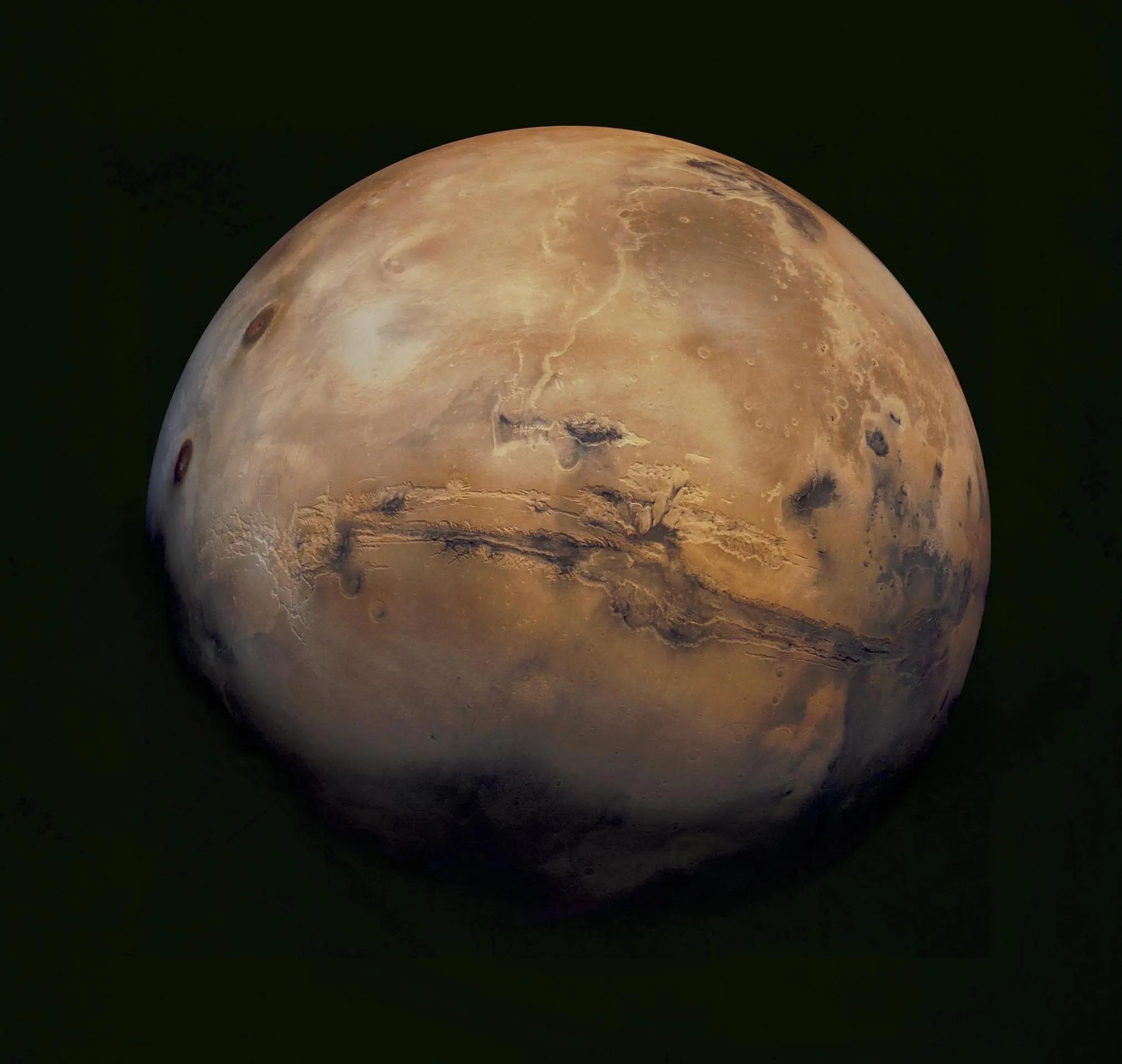

Mars is a reminder that “rocky” doesn’t mean “Earth-like.” A thin atmosphere changes the climate story.

What to notice: Mars is a cold, rocky world with a thin atmosphere — a contrast case for climate and habitability. (Credit: NASA)

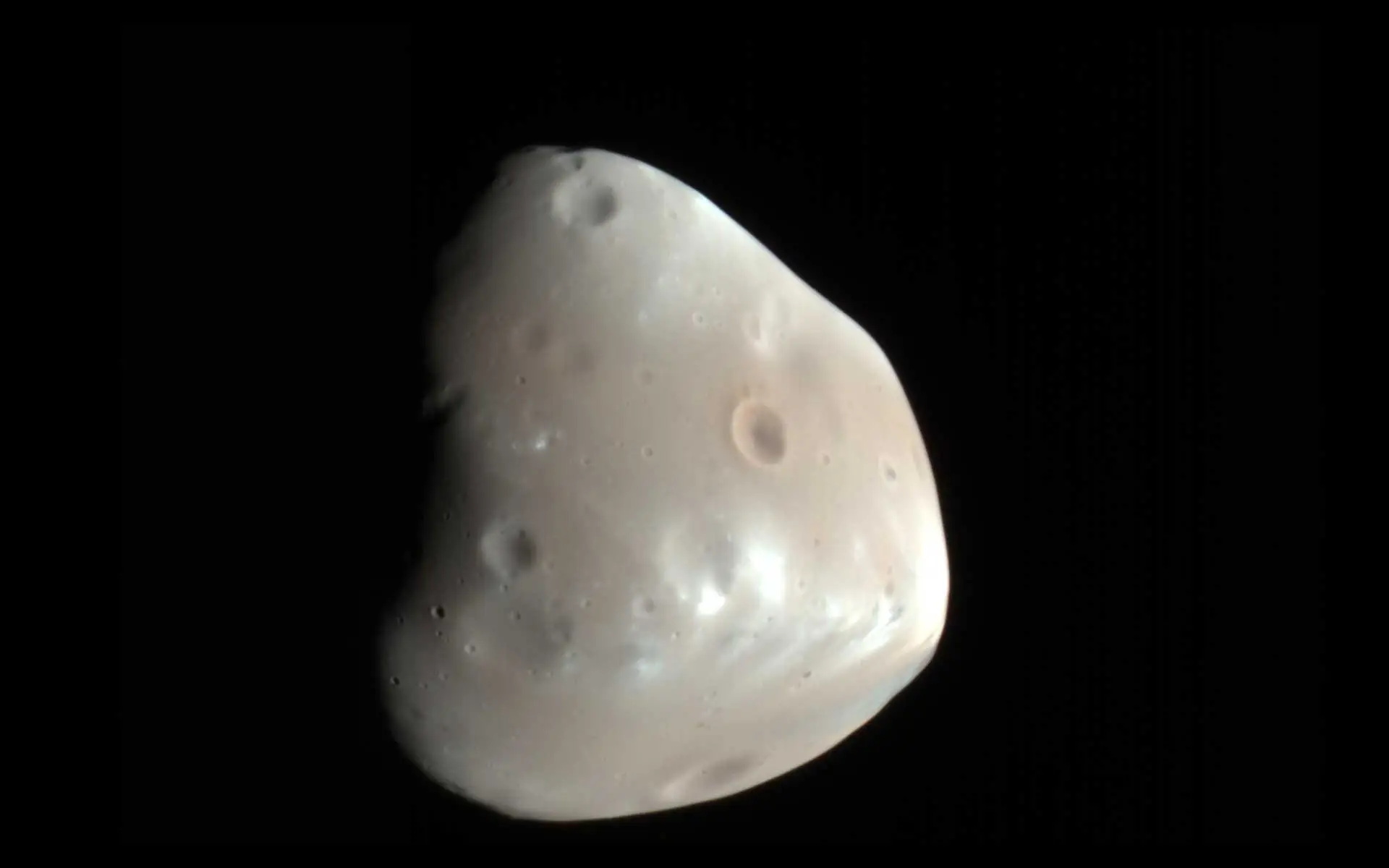

Mars also has two tiny, irregular moons — more like captured asteroids than scaled-down versions of our Moon.

What to notice: Small moons can be irregular and heavily cratered — they look more like asteroids than planets. (Credit: NASA)

What to notice: Deimos is tiny and irregular — evidence that not all moons form the same way.

The asteroid belt: leftovers and building blocks

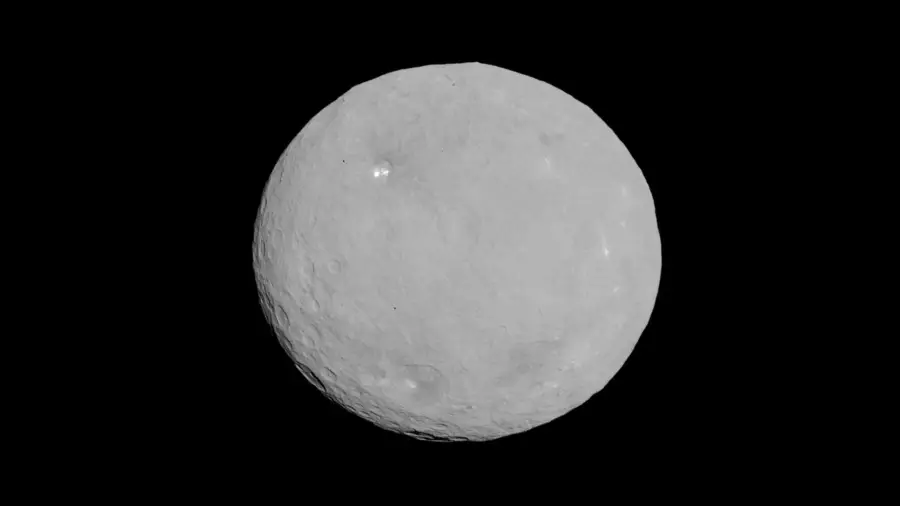

The asteroid belt is made of leftovers, not “mini-planets.” But it still contains large bodies — including the dwarf planet Ceres.

What to notice: The asteroid belt contains large bodies too — Ceres is a dwarf planet with its own geology. (Credit: NASA)

Giant planets: atmospheres without a surface

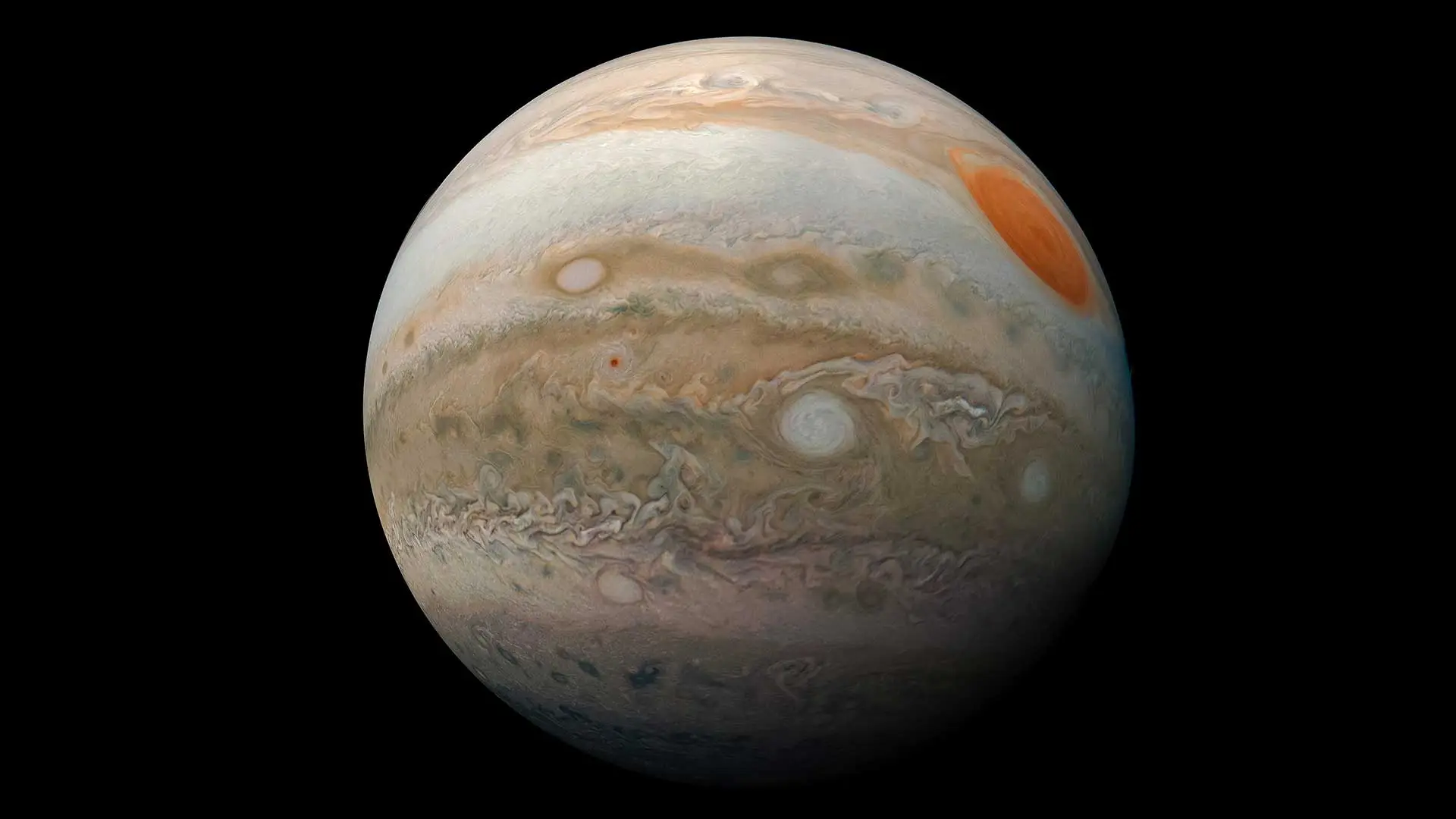

Jupiter and Saturn are dominated by atmosphere: bands, storms, and deep fluid layers. The familiar “surface” is actually cloud tops.

What to notice: Jupiter is a gas giant with banded cloud layers — atmosphere, not a solid surface, dominates what we see. (Credit: NASA)

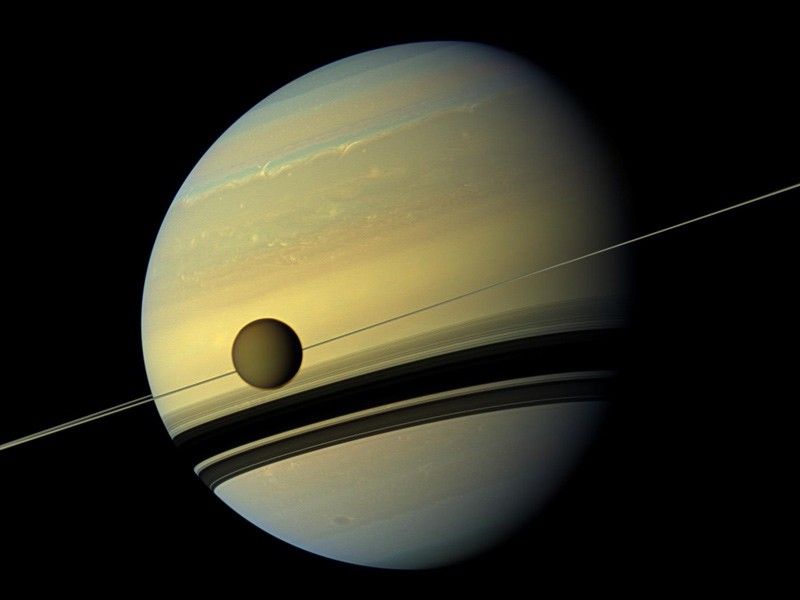

Saturn adds the most obvious disk in the solar system: its rings.

What to notice: Saturn’s rings make its structure obvious: a planet plus a disk of countless small particles. (Credit: NASA)

And moons can be worlds too — Titan has a thick atmosphere that hides its surface in visible light.

What to notice: Titan is a moon with a thick atmosphere — moons can have their own ‘planet-like’ complexity. (Credit: NASA)

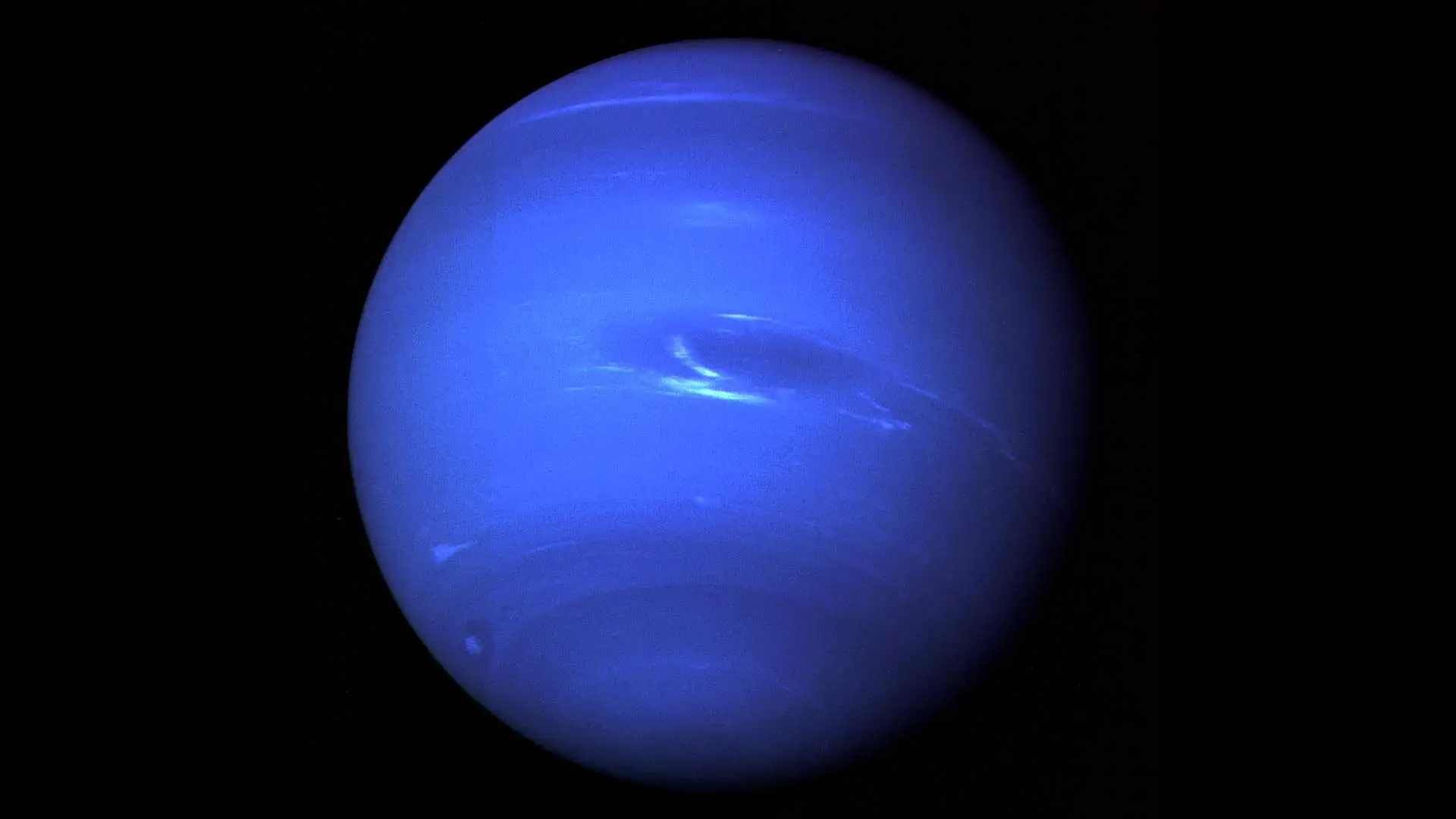

Ice giants and beyond: cold, distant, and still active

Uranus and Neptune are colder and smaller than Jupiter and Saturn, with different compositions and atmospheric chemistry.

What to notice: The ice giants are distant and cold — their atmospheres and compositions differ from Jupiter and Saturn. (Credit: NASA)

What to notice: Neptune’s deep blue color and storms emphasize that ice giant atmospheres can be active. (Credit: NASA)

Pluto is a signpost: the outer solar system contains many icy worlds and dwarf planets beyond the eight planets.

What to notice: Pluto lives in the Kuiper Belt — the outer solar system includes dwarf planets and icy worlds, not just the eight planets. (Credit: NASA)

Part 2: Applying Our Toolkit

How Do We Know What We Know?

We’ve never brought back samples from Jupiter. We’ve never landed on Neptune. Yet we know their masses, compositions, temperatures, and rotation rates. How?

Everything comes from the physics of Module 1.

This is the power of remote sensing. Light carries information across billions of kilometers, and our toolkit lets us decode it.

| What We Measure | The Tool | The Physics |

|---|---|---|

| Distance from Earth | Radar ranging | Round-trip light travel time |

| Distance from Sun (a) | Kepler III (once P known) | \(P^2 \propto a^3\) |

| Orbital period | Observation over time | Track position against stars |

| Mass (with moons) | Moon orbits + Newton | \(M = \frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{GP^2}\) |

| Mass (no moons) | Spacecraft tracking | Gravity bends spacecraft path |

| Temperature | IR spectrum + Wien | Peak wavelength → temperature |

| Composition | Spectral lines | Absorption/emission fingerprints |

| Rotation rate | Repeated imaging + Doppler | Track patterns; measure broadening |

| Wind speeds | Doppler + cloud tracking | Line-of-sight speeds; pattern motion |

Worked Example: Jupiter’s Mass from Io’s Orbit

Let’s apply Newton’s form of Kepler’s Third Law to measure Jupiter’s mass.

Problem: Jupiter’s moon Io orbits at a = 422,000 km with period P = 1.77 days. Find Jupiter’s mass.

Solution:

Step 1: Convert units to SI

- a = 422,000 km = 4.22 × 10⁸ m

- P = 1.77 days × 86,400 s/day = 1.53 × 10⁵ s

Step 2: Apply Newton’s version of Kepler III

\[M = \frac{4\pi^2 a^3}{GP^2}\]

Step 3: Plug in numbers

\[M = \frac{4\pi^2 (4.22 \times 10^8)^3}{(6.67 \times 10^{-11})(1.53 \times 10^5)^2}\]

\[M = \frac{4\pi^2 \times 7.51 \times 10^{25}}{6.67 \times 10^{-11} \times 2.34 \times 10^{10}}\]

\[M = \frac{2.97 \times 10^{27}}{1.56} = 1.9 \times 10^{27} \text{ kg}\]

This is 318 Earth masses — determined entirely by watching Io orbit! We never touched Jupiter. We just measured Io’s orbit and applied Newton’s gravity.

Observable: Io orbits Jupiter at 422,000 km with period 1.77 days. (Position + Timing)

Model: Newton’s form of Kepler III: \(M = 4\pi^2 a^3 / (GP^2)\)

Inference: Jupiter’s mass is \(1.9 \times 10^{27}\) kg = 318 Earth masses.

Same pattern as always: measurement → physics → knowledge.

If a planet has a moon orbiting at twice the distance but with the same orbital period, what can you conclude about the planet’s mass compared to another planet with the original moon orbit?

- The same mass

- 2× the mass

- 4× the mass

- 8× the mass

D) 8× the mass. From \(M = 4\pi^2 a^3 / (GP^2)\), if \(a\) doubles and \(P\) stays the same, \(M\) must increase by \(2^3 = 8\) times. Larger orbits at the same period require stronger gravity → more mass.

Which tool would you use to measure Jupiter’s mass if it had NO moons?

- Wien’s Law

- Spectroscopy

- Track a spacecraft’s path as it flies by

- Doppler effect on Jupiter’s light

C) Track a spacecraft’s path as it flies by. Without moons, we can’t use Newton’s form of Kepler III. But a spacecraft passing Jupiter gets deflected by gravity — by measuring how much the path bends, we can calculate Jupiter’s mass. This is how we measure masses of moonless asteroids and comets.

Temperature from Wien’s Law

Planets Glow in the Infrared

Every planet emits thermal radiation. Using Wien’s Law from L8:

\[\lambda_{\text{peak}} = \frac{2.9 \times 10^6 \text{ nm}}{T}\]

We can measure a planet’s peak emission wavelength and calculate its temperature. For most planets, this peak is in the infrared — invisible to our eyes but detectable by IR telescopes.

Equilibrium Temperature: A Baseline Prediction

Equilibrium temperature is what a planet’s temperature would be if:

- It absorbed sunlight and re-radiated as a blackbody

- It had no atmosphere (no greenhouse effect)

- Temperature was averaged over the whole surface

It’s a baseline prediction from Stefan-Boltzmann. When the observed temperature differs from equilibrium, something interesting is happening.

Equilibrium temperature is a prediction — what physics says “should” happen with just sunlight in, thermal radiation out.

Observed temperature is what we measure.

When they differ, something interesting is happening:

- Venus: Observed >> Equilibrium → massive greenhouse effect

- Jupiter: Observed > Equilibrium → internal heat source

- Mercury: Observed ≈ Equilibrium (on average) → no atmosphere

Always compare the two to diagnose what’s going on!

Planetary Temperature Comparison

| Planet | Distance (AU) | T_equilibrium (K) | T_observed (K) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mercury | 0.39 | ~440 | ~90–700 | No atmosphere → extreme day/night swing |

| Venus | 0.72 | ~230 | 735 | Runaway greenhouse! |

| Earth | 1.0 | ~255 | 288 | Moderate greenhouse (+33 K) |

| Mars | 1.52 | ~210 | 218 | Thin atmosphere (+8 K) |

| Jupiter | 5.2 | ~110 | ~165 | Internal heat source adds ~55 K |

Mercury’s extremes illustrate what happens without an atmosphere: daytime reaches 700 K (430°C), but nighttime plunges to 90 K (-180°C). That 600°C swing would be impossible with an atmosphere to redistribute heat.

Technically, Mercury has an exosphere — an extremely thin envelope of atoms (sodium, potassium, oxygen, hydrogen) that are constantly escaping to space and being replenished by solar wind bombardment, micrometeorite impacts, and outgassing from the surface.

The exosphere is so thin (surface pressure < ~10⁻¹² bar, compared to Earth’s 1 bar) that atoms rarely collide with each other. It provides essentially no insulation, no heat redistribution, no greenhouse effect — which is why Mercury’s temperature swings are so extreme.

For our purposes: Mercury effectively has “no atmosphere” in the thermodynamic sense that matters for climate.

Venus stands out: its actual temperature is 500 K hotter than equilibrium! This is the greenhouse effect at its most extreme — and we’ll explore it in L12.

Venus is nearly Earth’s twin in size and mass. Scientists believe it may have had Earth-like conditions early in its history — possibly even liquid water oceans. So what went wrong?

In L12, we’ll trace Venus’s transformation from potentially habitable world to 735 K hellscape. The culprit: a runaway greenhouse effect triggered by Venus being slightly too close to the Sun. It’s a story with implications for understanding climate here on Earth.

Jupiter is warmer than equilibrium because it has an internal heat source — leftover heat from its formation, still slowly radiating away after 4.6 billion years.

Mercury and Venus are both “hot” planets. Which tool would help you distinguish “hot because close to Sun” from “hot because greenhouse effect”?

- Compare observed temperature to equilibrium temperature

- Measure the planet’s mass

- Count the planet’s moons

- Measure the planet’s orbital period

A) Compare observed temperature to equilibrium temperature. Mercury’s temperature roughly matches what you’d expect from its distance (equilibrium). Venus is 500 K hotter than equilibrium — that huge gap reveals the greenhouse effect is doing something extreme. This is exactly how we diagnosed Venus’s climate.

Compositions from Spectroscopy

Atmospheric Fingerprints

By observing planets at different wavelengths and looking for spectral lines (L9), we determine atmospheric compositions. Each molecule absorbs at specific wavelengths — its spectral fingerprint.

- Venus: CO₂ (96%), N₂ (3.5%), sulfuric acid clouds

- Earth: N₂ (78%), O₂ (21%), trace CO₂, H₂O

- Mars: CO₂ (95%), N₂ (2.7%), thin atmosphere

- Jupiter: H₂ (~90%), He (~10%), traces of CH₄, NH₃, H₂O

The same spectroscopy that identifies elements in stars identifies molecules in planetary atmospheres! The physics is identical — just applied to different objects.

Color as a Clue

Sometimes a planet’s color hints at its composition. Neptune and Uranus appear blue-green because methane (CH₄) in their atmospheres absorbs red light, leaving the blue to be reflected back to us.

Mars appears red for a different reason — not atmospheric absorption, but iron oxide (rust!) on its surface.

Mars appears red to our eyes. Neptune appears blue. Using concepts from L7-L9, which planet likely has methane (CH₄) in its atmosphere?

- Mars — red color means methane

- Neptune — methane absorbs red light, leaving blue

- Both have methane

- Neither has methane

B) Neptune — methane absorbs red light, leaving blue. Spectroscopy confirms that Neptune (and Uranus) have methane in their atmospheres. Methane absorbs red wavelengths, so the reflected sunlight appears blue. Mars is red because of iron oxide (rust) on its surface, not atmospheric absorption.

Part 3: Solar System Formation

The solar system’s layout is fossil evidence. Rocky worlds huddle inside. Gas giants patrol the outer system. A belt of rubble sits where a fifth rocky planet might have formed. Icy debris extends to the edge of the Sun’s gravitational influence.

This isn’t random. It’s the preserved record of what happened 4.6 billion years ago. If we can read the pattern, we can reconstruct the story.

The Nebular Hypothesis

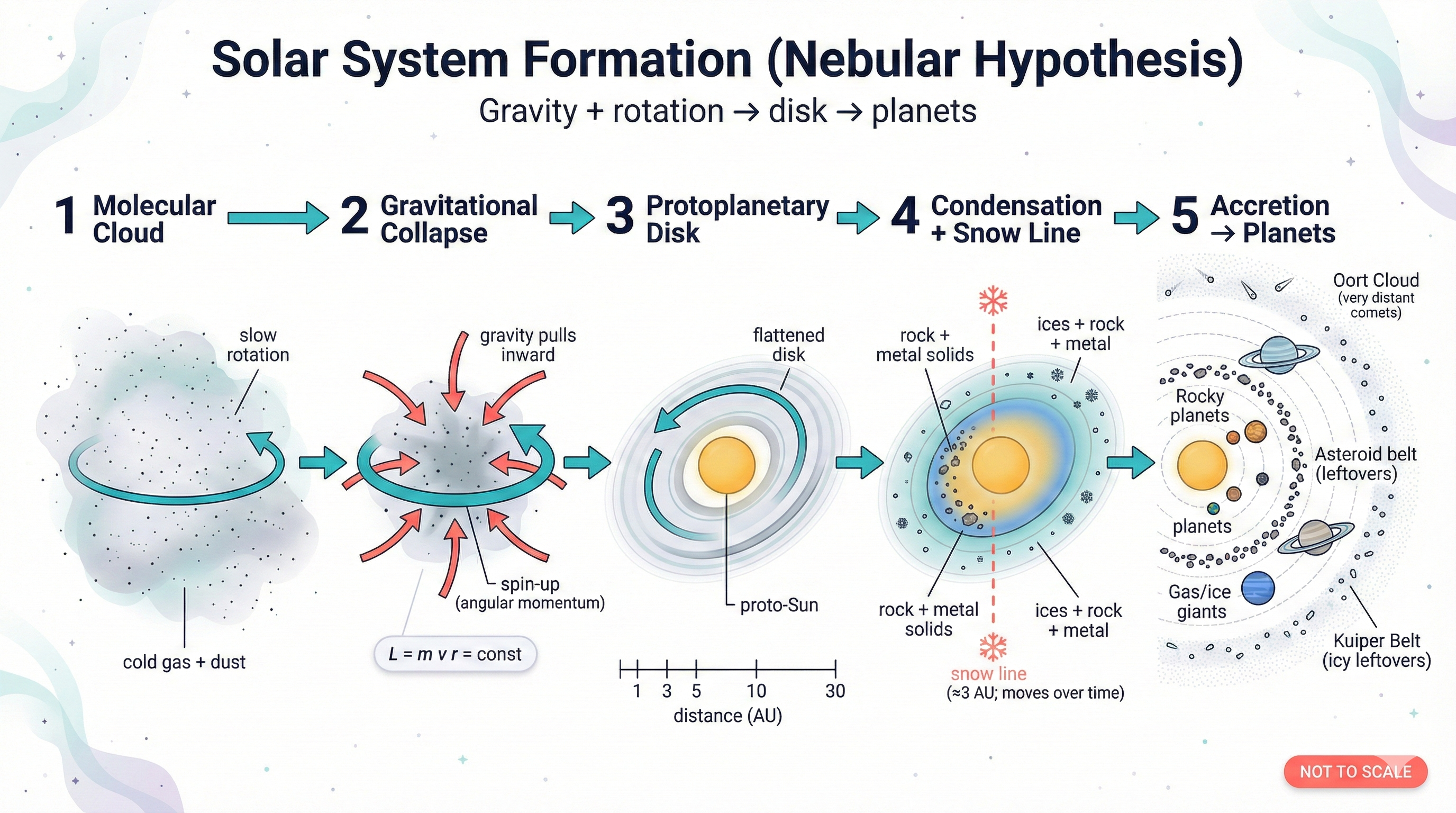

How did the solar system form? The leading model — the nebular hypothesis — explains why the solar system looks the way it does.

The solar system formed ~4.6 billion years ago from a collapsing cloud of gas and dust called the solar nebula. Here’s the cause → effect chain:

What to notice: The nebular hypothesis starts with a rotating disk of gas and dust. Collisions and gravity flatten the system into a plane, which is why most planets end up orbiting in nearly the same plane and direction.

1. Gravity → Collapse

A region of a molecular cloud becomes dense enough to collapse under its own gravity.

2. Collapse → Spin-up (Angular momentum conservation)

As the cloud shrinks, it spins faster — just like a figure skater pulling in their arms.

3. Spin-up + Collisions → Disk

Rotation + collisions damp vertical motions, so material settles into a thin disk while continuing to orbit the center.

4. Temperature gradient → Condensation sequence

Inner disk is hot (only rock/metal condenses); outer disk is cold (ices also condense).

5. Core growth outside snow line → Gas capture

More solid material → bigger cores → gravitational capture of H/He → gas giants.

Memorize this ladder. You can reconstruct the whole story from these five steps.

What to notice: formation as a causal chain — collapse spins up a rotating disk, temperature sets a condensation sequence, and the snow line separates rocky from ice-rich building blocks. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — illustrative))

Angular Momentum: The L5-L6 Connection

Remember the figure skater from L5? Arms out = slow spin; arms in = fast spin.

The same physics explains why the solar nebula spun up as it collapsed:

\[L = mvr = \text{constant}\]

As \(r\) decreases (cloud shrinks), \(v\) must increase (faster rotation).

This is why:

- The Sun rotates (slowly — most angular momentum went to planets)

- All planets orbit in the same direction

- All planets orbit in nearly the same plane

- The disk formed in the first place!

The Frost Line: Rocky vs. Gas Giants

Why Rocky Inside, Gas Outside?

The frost line (or snow line) is the distance from the young Sun where it was cold enough for water and other volatiles to freeze into solid ice.

- Inside the frost line (~3 AU): Too hot for ices; only rock and metal could condense

- Outside the frost line: Ices could form, providing much more solid material

The ~3 AU value is a useful order-of-magnitude for the early solar nebula, but the snow line isn’t a fixed wall. It moves over time as the disk evolves and the young Sun’s luminosity changes. Early on, when the Sun was dimmer, the frost line may have been closer; as the disk heated up during active accretion, it moved outward.

For ASTR 101: ~3 AU captures the essential physics. Just don’t think of it as a permanent, sharp boundary.

The Consequence

Rocky planets formed close to the Sun because only rock/metal was available as solid building blocks.

Beyond the frost line, ices added to the solids, allowing larger cores to form. These massive cores could gravitationally capture hydrogen and helium from the nebula → gas giants!

| Region | Solid Material Available | Result |

|---|---|---|

| Inside frost line | Rock, metal only | Small rocky planets |

| Outside frost line | Rock + metal + ices | Large cores → capture H/He → gas giants |

Why didn’t Earth become a gas giant like Jupiter?

- Earth formed before Jupiter

- There wasn’t enough hydrogen near Earth

- Earth was inside the frost line, so its core stayed small

- Jupiter stole all the gas

C) Earth was inside the frost line, so its core stayed small. Inside the frost line, only rock and metal could form solid particles. Without the extra mass from ices, Earth’s core never grew large enough to gravitationally capture the abundant hydrogen and helium gas.

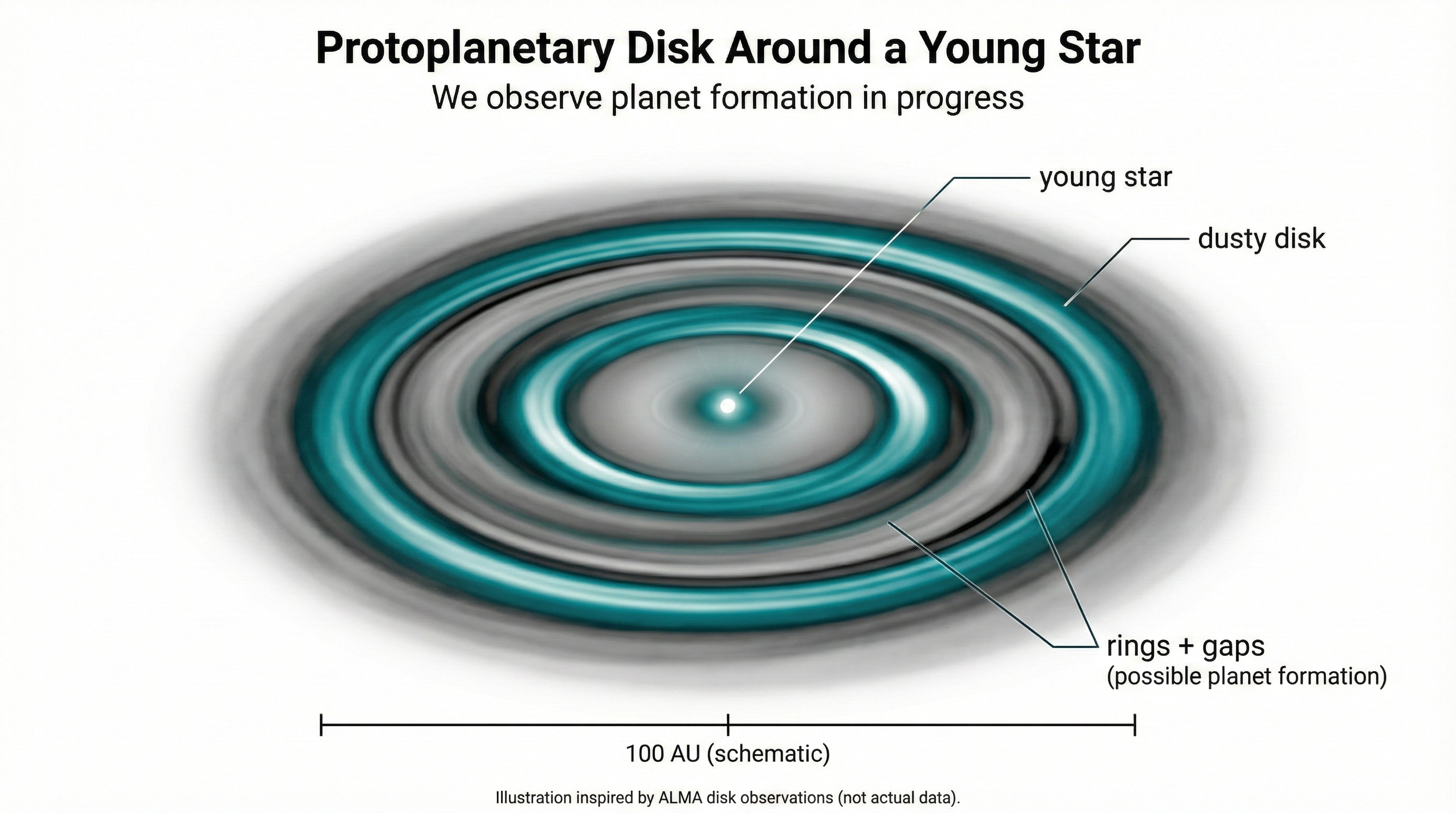

Evidence for the Nebular Hypothesis

How do we know this model is correct? The solar system shows clear signatures:

All planets orbit in the same direction — inherited from the disk’s rotation

All planets orbit in nearly the same plane — the disk was flat

Rocky planets inside, giants outside — explained by the frost line

Asteroid belt — Jupiter’s gravity and resonances inhibited planet formation

Meteorites — pristine samples from early solar system, dated to 4.6 billion years

We observe protoplanetary disks around other young stars!

What to notice: we observe planet formation in progress — rings and gaps in young-star disks can be signatures of emerging planets. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — illustrative))

Most planets orbit in the same plane and direction — but many moons are exceptions. Some moons are captured asteroids orbiting at odd angles (like Triton, which orbits Neptune backwards). Some moons formed from giant impacts (like Earth’s Moon).

The planet pattern supports the disk story. Moon orbits are messier because moons have additional formation pathways beyond the original disk.

Solar System Architecture:

- Rocky planets (Mercury–Mars) inside ~1.5 AU

- Gas giants (Jupiter, Saturn) at 5–10 AU

- Ice giants (Uranus, Neptune) at 19–30 AU

- Small bodies: asteroid belt, Kuiper Belt, Oort Cloud

Applying Our Toolkit:

- Masses from moon/spacecraft orbits (Newton’s gravity, L6)

- Temperatures from IR observations (Wien’s Law, L8)

- Compositions from spectral lines (L9)

- Everything connects back to Module 1!

Formation (The Causal Chain):

- Collapse → spin-up → disk → temperature gradient → condensation

- Angular momentum conservation explains disk formation and orbital patterns

- Frost line (~3 AU, model-dependent) explains rocky vs. gas giant distribution

Practice Problems

Core (do these first)

1. Kepler Application: Mars orbits the Sun at 1.52 AU. Using Kepler’s Third Law (\(P^2 = a^3\) in Earth years and AU), calculate Mars’s orbital period.

2. Newton Application: Saturn’s moon Titan orbits at 1.22 million km with a period of 16 days. Estimate Saturn’s mass. (Compare to Jupiter’s mass from the worked example.)

3. Wien Application: Neptune’s thermal emission peaks at about 50 μm (50,000 nm). Estimate Neptune’s temperature using Wien’s Law.

4. Formation Concept: Explain why all the planets orbit the Sun in the same direction and in nearly the same plane.

Challenge

5. Frost Line Reasoning: If the Sun had been twice as luminous when the solar system formed, how would the frost line have been different? What consequences might this have for the distribution of planet types?

6. Integration Problem: You discover an exoplanet system where rocky planets extend out to 5 AU. What might this tell you about the host star compared to our Sun?

7. Tool Choice: You want to determine whether a newly discovered exoplanet is rocky or gaseous. What two measurements would you need, and which tools from Module 1 would provide them?

Glossary

No glossary terms for lecture 11.