Planetary Climates & Finding Other Worlds

Lecture 12 Reading Companion

Planet climates are an energy-balance problem. Sunlight in, infrared out. Equilibrium temperature is the baseline; atmospheres (greenhouse gases, clouds, pressure) push real surface temperatures above or below that baseline. The same physics that explains Venus, Earth, and Mars is what we use to judge exoplanet habitability — after we find those planets using transits and radial velocity.

This reading has two main parts:

Part 1: Planetary Climates (~25 min)

- Why planetary temperatures differ from simple predictions

- The greenhouse effect explained

- Venus vs. Earth vs. Mars: what went wrong/right

- Climate change connection

Part 2: Exoplanet Detection (~20 min)

- Transit method (geometry callback to L4!)

- Combining with radial velocity (L10)

- The habitable zone

Exam connection: This lecture reinforces L8 (blackbody/Stefan-Boltzmann) and L10 (Doppler). Climate physics applies thermal equilibrium. Transit detection applies geometry from L4.

What’s next: L13 asks the big question: Are we alone? We’ll use the Drake Equation to estimate how many civilizations might exist.

If you only remember three things:

Greenhouse effect: Atmospheres absorb some outgoing infrared, warming the surface above equilibrium. Venus = extreme (+500 K), Earth = moderate (+33 K), Mars = minimal (+8 K).

Transits detect exoplanets: When a planet crosses its star, brightness dips by \((R_p/R_*)^2\). Combined with radial velocity → mass + radius → density → rocky or gaseous?

Habitable zone: Where liquid water could exist. Depends on stellar luminosity and planetary atmosphere. Zone ≠ guarantee!

Now for the details…

Three Worlds, Three Fates

Venus, Earth, and Mars are siblings — rocky planets that formed from the same solar nebula about 4.6 billion years ago. You might expect similar conditions. Instead, we find three radically different worlds:

Venus: Surface temperature 735 K (462°C) — hot enough to melt lead. Crushing atmospheric pressure 90× Earth’s. Sulfuric acid clouds. No liquid water. A hellscape.

Earth: Surface temperature 288 K (15°C). Moderate atmosphere. Liquid water oceans covering 70% of the surface. Life everywhere, from deep ocean vents to Antarctic ice.

Mars: Surface temperature 218 K (-55°C). Atmospheric pressure less than 1% of Earth’s. Frozen polar caps. Ancient river channels, but no liquid water today. A cold desert.

What explains these vastly different outcomes? The answer involves physics we’ve already learned: blackbody radiation, thermal equilibrium, and atmospheric absorption. Today we’ll see how the greenhouse effect creates these different climates — and why adding CO₂ to Earth’s atmosphere shifts the same energy balance (though in a vastly different regime than Venus).

Then we’ll turn to the search for other worlds. We’ve found thousands of exoplanets, some in “habitable zones” where liquid water could exist. How do we find them? And what determines if they’re actually habitable?

Before we dive in, see if you can answer these from memory:

- L8: What law relates an object’s temperature to the total power it radiates per unit area?

- L8: If an object’s temperature doubles, by what factor does its radiated power increase?

- L10: When a star moves toward us, are its spectral lines blueshifted or redshifted?

- L4: Why don’t we see a solar eclipse every month?

- Stefan-Boltzmann Law

- 16× (since P ∝ T⁴)

- Blueshifted

- Moon’s orbit is tilted ~5° relative to the ecliptic — alignment is rare

Part 1: Planetary Climates

Equilibrium Temperature — A First Guess

In L8, we learned that objects in thermal equilibrium absorb and emit energy at equal rates. For a planet absorbing sunlight:

\[\text{Energy absorbed} = \text{Energy emitted}\]

This gives an equilibrium temperature — what the planet’s temperature should be if it’s just balancing incoming sunlight against outgoing thermal radiation.

Equilibrium temperature: The temperature a planet would have if it only balanced absorbed sunlight against blackbody emission, with no atmospheric effects.

Deep Dive: Deriving Equilibrium Temperature

Let’s work through the calculation step by step.

Step 1: Energy Balance

At equilibrium, energy in equals energy out:

\[\text{Power absorbed from Sun} = \text{Power radiated to space}\]

We already know the right side from L8: a blackbody radiates power according to the Stefan-Boltzmann Law:

\[P_{out} = \sigma T^4 \times (\text{surface area})\]

This is the key connection! The Stefan-Boltzmann Law from L8 tells us how much power a planet radiates at temperature T. Setting this equal to absorbed sunlight gives us the equilibrium temperature.

But how much solar power does a planet actually intercept?

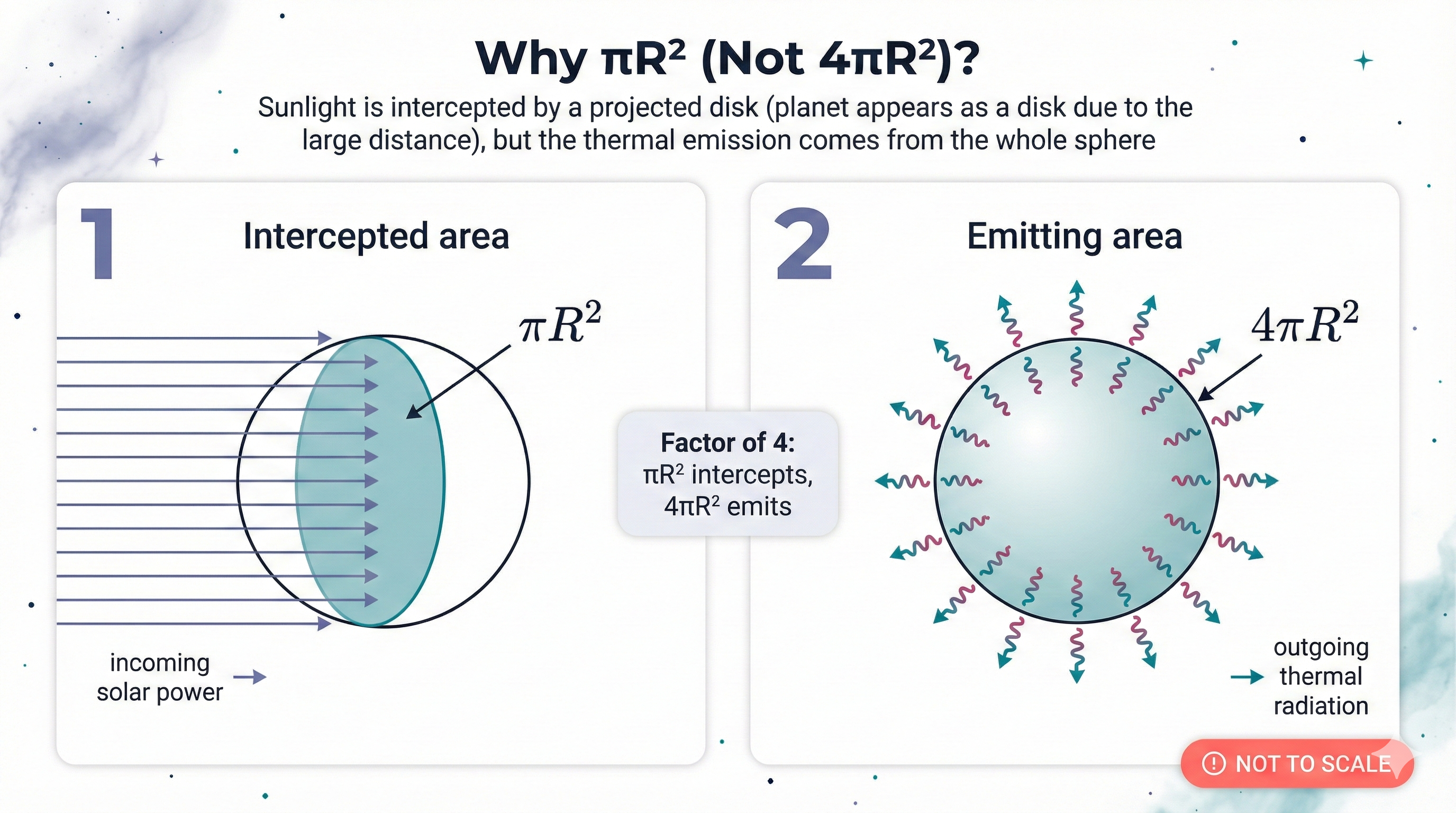

Step 2: Why πR², Not 4πR²? — The Disk Approximation

Here’s a key insight: A planet doesn’t absorb sunlight over its entire spherical surface. Sunlight comes from one direction (the Sun), so the planet only intercepts light across its cross-sectional area — the area of the “shadow” it would cast.

During a total solar eclipse, the Moon blocks the Sun. But the Moon’s shadow on Earth isn’t sphere-shaped — it’s a disk. That’s because sunlight travels in parallel rays from the distant Sun, and the Moon intercepts them with its cross-sectional area.

Cross-section of a sphere = πR² (the area of a circle with the same radius)

The planet intercepts sunlight like a disk (πR²) but radiates from its entire spherical surface (4πR²). This factor of 4 difference is crucial for the calculation!

What to notice: a planet intercepts sunlight over its projected disk (πR²) but emits thermal radiation from its whole surface (4πR²) — that factor of 4 is why equilibrium temperatures use 16π in the denominator. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

Step 3: What Is Albedo?

Not all sunlight that hits a planet gets absorbed — some reflects back into space. Albedo (A) is the fraction of incoming light that reflects away.

- Albedo = 0 → perfectly absorbing (all light absorbed)

- Albedo = 1 → perfectly reflecting (all light bounces off)

- Real planets: somewhere in between

These are Bond albedos — the fraction of total incoming energy reflected, averaged over all wavelengths and angles. (Geometric albedo, which you may see elsewhere, measures reflectivity at a single viewing angle.)

| Body | Bond Albedo | Why? |

|---|---|---|

| Venus | ~0.76 | Thick, bright sulfuric-acid clouds reflect most light |

| Earth | ~0.30 | Mix of clouds, oceans (dark), ice (bright) |

| Mars | ~0.25 | Dusty, rocky surface with thin atmosphere |

| Moon | ~0.11 | Dark basalt surface, no atmosphere |

Albedo (Bond): The fraction of total incoming energy reflected back to space, averaged over all wavelengths and angles. Used for energy-balance calculations.

If a planet reflects fraction A, it absorbs fraction (1 - A).

- Venus absorbs only 25% of incoming sunlight

- Earth absorbs 70%

- Mars absorbs 75%

Venus has the highest albedo of these planets — it reflects most of its sunlight! This should make it cooler than Earth. The fact that Venus is instead the hottest planet in the solar system (even hotter than Mercury) tells you how powerful its greenhouse effect is.

Step 4: Putting It All Together

Now we can set up the full energy balance:

Power absorbed:

\[P_{in} = (\text{Solar flux at planet}) \times (\text{cross-section}) \times (1 - A)\]

The solar flux at distance \(d\) from the Sun is:

\[F = \frac{L_\odot}{4\pi d^2}\]

So:

\[P_{in} = \frac{L_\odot}{4\pi d^2} \times \pi R^2 \times (1 - A)\]

Power radiated:

\[P_{out} = \sigma T_{eq}^4 \times 4\pi R^2\]

Setting them equal:

\[\frac{L_\odot}{4\pi d^2} \times \pi R^2 \times (1 - A) = \sigma T_{eq}^4 \times 4\pi R^2\]

Notice that \(\pi R^2\) appears on both sides — the planet’s size cancels out! This is why equilibrium temperature doesn’t depend on planet size.

Solving for \(T_{eq}\):

\[T_{eq} = \left[ \frac{(1-A) L_\odot}{16\pi \sigma d^2} \right]^{1/4}\]

Looking at the formula:

\[T_{eq} = \left[ \frac{(1-A) L_\odot}{16\pi \sigma d^2} \right]^{1/4}\]

The equilibrium temperature depends on:

- Distance (d): Farther → lower T_eq (goes as \(d^{-1/2}\))

- Albedo (A): Higher albedo → lower T_eq (absorbs less)

- Stellar luminosity (L): Brighter star → higher T_eq

It does NOT depend on:

- Planet radius (canceled out!)

- Planet mass

- Whether the planet has an atmosphere (that comes later!)

Equilibrium temperature is a model, not a measurement.

\(T_{eq}\) is what a bare, airless sphere would have if it only balanced absorbed sunlight against blackbody emission. Real surface temperatures differ because:

- Atmospheres trap heat (greenhouse effect)

- Planets rotate, redistributing heat

- Internal heat sources (e.g., Jupiter radiates more than it absorbs)

When you see a planet’s “temperature” in the news, ask: equilibrium, effective, or surface? They’re different numbers.

Simplified Formula for Quick Estimates

For a perfectly absorbing planet (A = 0) orbiting the Sun:

\[T_{eq} \approx 279\text{ K} \times \left(\frac{1\text{ AU}}{d}\right)^{1/2}\]

To correct for albedo, multiply by \((1-A)^{1/4}\):

\[T_{eq} \approx 279\text{ K} \times (1-A)^{1/4} \times \left(\frac{1\text{ AU}}{d}\right)^{1/2}\]

Sanity check for Earth (d = 1 AU, A ≈ 0.30):

\[T_{eq} \approx 279 \times (0.70)^{1/4} \approx 279 \times 0.91 \approx 255\text{ K}\]

That matches the table below — and it’s about 33 K colder than Earth’s actual surface temperature. The difference? The greenhouse effect.

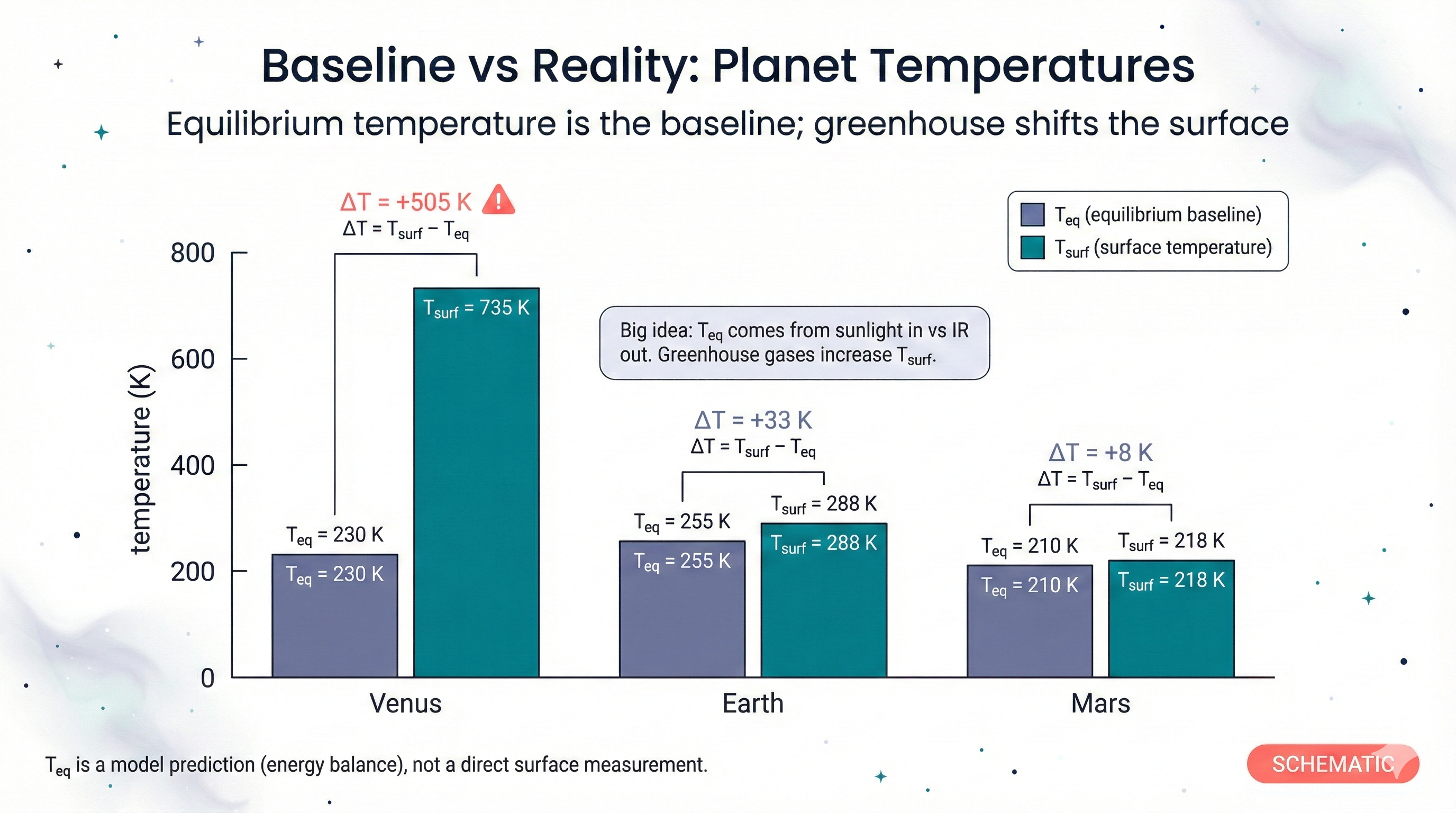

The Predictions vs. Reality

| Planet | Distance (AU) | T_equilibrium (K) | T_actual (K) | Difference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Venus | 0.72 | ~230 | 735 | +505 K ⚠️ |

| Earth | 1.00 | ~255 | 288 | +33 K |

| Mars | 1.52 | ~210 | 218 | +8 K |

Something is very wrong with our prediction for Venus. It’s 500 degrees hotter than equilibrium! Earth is also warmer than expected, but by a modest 33 K. What’s going on?

What to notice: equilibrium temperature is a baseline from sunlight-in vs IR-out; greenhouse physics shifts the real surface temperature above that baseline by different amounts on Venus, Earth, and Mars. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

Based only on distance from the Sun, which planet should be warmest?

- Venus

- Earth

- Mars

- They should all be the same temperature

A) Venus. Closer to the Sun means more intense sunlight, so a higher equilibrium temperature. But Venus’s actual temperature is even higher than this prediction — that’s where the greenhouse effect comes in.

The Greenhouse Effect

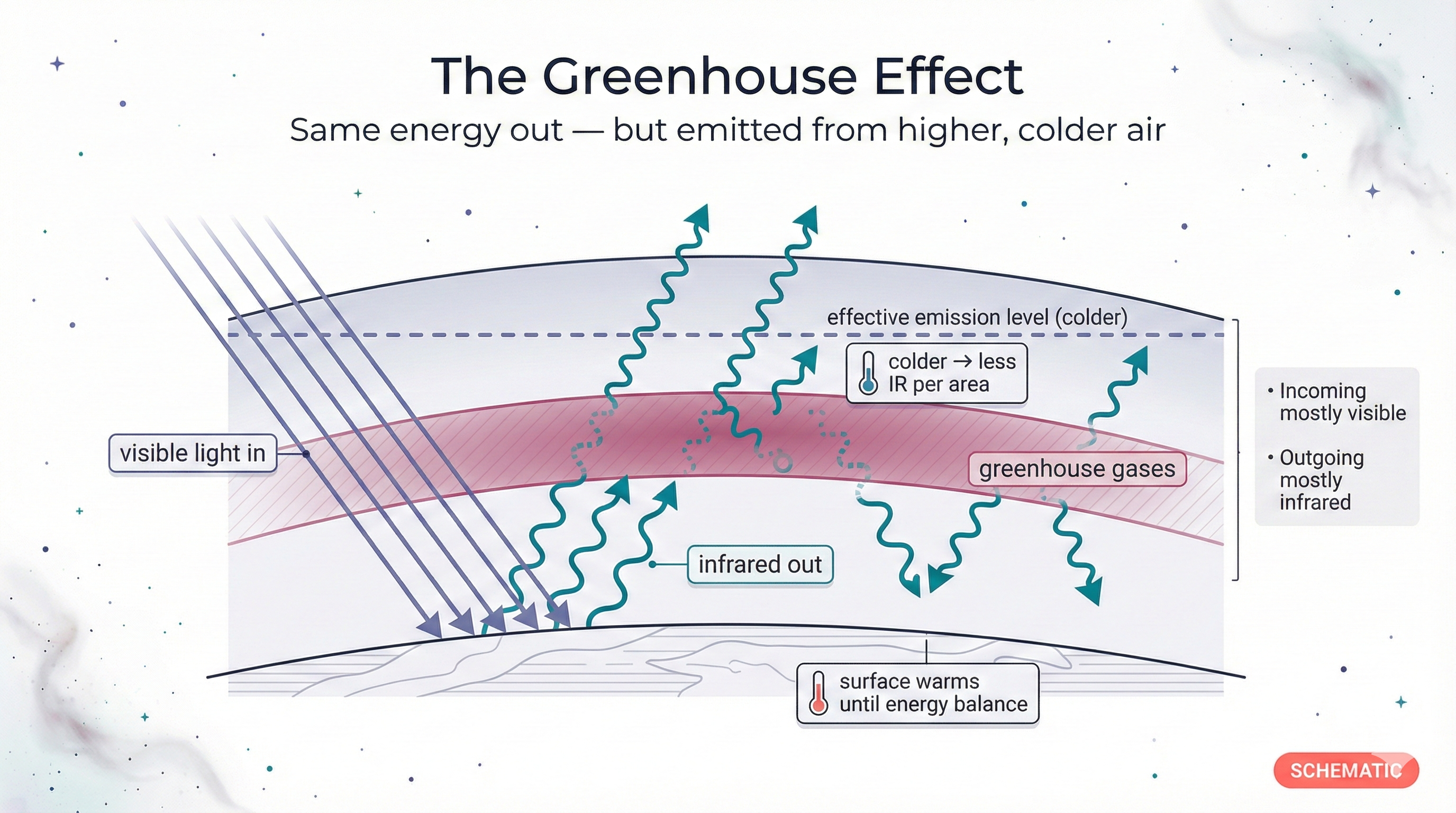

The Basic Mechanism

The equilibrium calculation assumes the planet radiates directly to space. But if the planet has an atmosphere containing greenhouse gases, something different happens:

Sunlight (visible) passes through the atmosphere and heats the surface

The surface emits infrared radiation (thermal, from Wien’s Law)

Greenhouse gases selectively absorb infrared — they’re transparent to visible light but absorb in key IR wavelength bands

The atmosphere re-radiates — some back down to the surface

The effective emission level moves higher in the atmosphere — where it’s colder. To radiate the same total power to space, the surface must warm up to compensate. (Think of it this way: the atmosphere acts like a blanket, so the skin under the blanket has to be warmer to maintain the same heat flow outward.)

What to notice: the same energy must leave to space, but greenhouse gases shift the effective emission level upward to colder air, so the surface warms until energy balance is restored. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

Key Greenhouse Gases

| Gas | Chemical Formula | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Water vapor | H₂O | Strong absorber; amplifies other effects |

| Carbon dioxide | CO₂ | Primary driver; very long-lived |

| Methane | CH₄ | Potent but shorter-lived |

| Nitrous oxide | N₂O | Long-lived, potent |

Why do greenhouse gases absorb infrared specifically?

From Wien’s Law: \(\lambda_{\text{peak}} = 2.9 \times 10^6 / T\) nm

- Sun (5800 K): Peak at ~500 nm (visible) → passes through atmosphere

- Earth (288 K): Peak at ~10,000 nm (infrared) → absorbed by greenhouse gases

The atmosphere is largely transparent to incoming visible light but selectively absorbs outgoing infrared in key wavelength bands. That’s the essence of the greenhouse effect!

Venus — Runaway Greenhouse

What Went Wrong on Venus?

Venus may have started with conditions similar to Earth — perhaps even with liquid water oceans. But it was closer to the Sun, so it was warmer. Here’s what may have happened:

Higher temperature → more water evaporates

Water vapor is a greenhouse gas → temperature rises further

More evaporation → more water vapor → more warming (positive feedback!)

Eventually: oceans boil completely

UV light breaks apart water vapor → hydrogen escapes to space

CO₂ from volcanoes accumulates (no oceans to dissolve it, no life to sequester it)

Result: 96% CO₂ atmosphere, 735 K surface

The Runaway Greenhouse

This is a runaway greenhouse effect — a positive feedback loop where warming causes more warming until a new, much hotter equilibrium is reached.

Venus’s atmosphere is now 96% CO₂ with 90× Earth’s surface pressure. The greenhouse effect adds over 500 K to its temperature.

Venus shows what happens when the greenhouse effect runs away.

The same radiative physics governs all planetary climates — but Earth and Venus occupy vastly different regimes. Earth is not on a trajectory toward Venus-style runaway; our solar flux is too low and our oceans act as a CO₂ buffer. What is happening: adding greenhouse gases shifts Earth’s energy balance, raising surface temperatures by degrees, not hundreds of degrees. Small shifts still have large consequences.

Venus is hotter than Mercury, even though Mercury is closer to the Sun. Why?

- Venus has a stronger magnetic field

- Venus has a thick CO₂ atmosphere causing a strong greenhouse effect

- Venus rotates more slowly

- Venus has active volcanoes

B) Venus has a thick CO₂ atmosphere causing a strong greenhouse effect. Mercury has almost no atmosphere, so it experiences huge day–night temperature swings (~700 K dayside, ~100 K nightside) with no greenhouse warming. Venus’s thick CO₂ atmosphere traps heat uniformly, raising the surface to ~735 K everywhere — hotter than Mercury’s dayside despite being farther from the Sun.

Mars — Too Little Atmosphere

Why Mars Is Cold

Mars has the opposite problem: its atmosphere is too thin to trap much heat.

- Surface pressure: 0.6% of Earth’s

- Composition: 95% CO₂, but so thin it barely matters

- Result: Only ~8 K of greenhouse warming

Mars also lost much of its early atmosphere. With weak gravity (38% of Earth’s) and no global magnetic field, the solar wind stripped away atmospheric gases over billions of years.

Evidence of Past Water

Mars wasn’t always this way. We see:

- Ancient river channels and lake beds

- Minerals that only form in liquid water

- Polar ice caps (CO₂ and water ice)

Early Mars may have had a thicker atmosphere and liquid water. Climate change — going the opposite direction from Venus — froze and dried the planet.

Earth — The Goldilocks Planet

Why Earth Works

Earth sits in a sweet spot:

Right distance: Warm enough for liquid water, cool enough to avoid runaway greenhouse

Right atmosphere: Enough greenhouse effect (~33 K) to avoid freezing, not too much

Carbon cycle: CO₂ dissolves in oceans, gets locked in rocks, volcanoes release it — a natural thermostat

Plate tectonics: Recycles carbon, renews atmosphere

Magnetic field: Protects atmosphere from solar wind stripping

The Climate Change Connection

Here’s where this matters for us today:

Burning fossil fuels releases CO₂ that was locked in rocks for millions of years. Humanity currently emits ~40 GtCO₂/yr (order-of-magnitude; exact values vary by year and accounting method); about half is absorbed by the ocean and biosphere, with the rest accumulating in the atmosphere.

The physics is exactly what we discussed:

- More CO₂ → more infrared absorption → less heat escapes → surface warms

- This is not speculation; it’s the same physics that explains Venus

Earth isn’t becoming Venus — we’re much too far from the Sun. But shifting Earth’s temperature by even a few degrees has major consequences: sea level rise, extreme weather, ecosystem disruption.

Climate science isn’t about politics — it’s about radiative transfer.

The greenhouse effect is the same physics that explains:

- Why Venus is hotter than Mercury

- Why Earth is 33 K warmer than its equilibrium temperature

- Why Mars is a frozen desert

Adding greenhouse gases changes the energy balance. That’s Stefan-Boltzmann and Kirchhoff’s Laws at work. The only question is how much and how fast.

Earth’s greenhouse effect raises the surface temperature about 33 K above equilibrium. If CO₂ levels increase, what happens?

- Temperature decreases because CO₂ reflects sunlight

- Temperature stays the same because equilibrium is fixed

- Temperature increases because more infrared is absorbed

- Temperature increases only at night

C) Temperature increases because more infrared is absorbed. More CO₂ means the atmosphere absorbs more outgoing infrared radiation. To restore energy balance, the surface must warm up to radiate more energy. This is the basic physics of climate change.

Part 2: Exoplanet Detection

Finding Other Worlds

The Challenge

Planets are tiny compared to stars and don’t produce their own visible light — they only reflect starlight. Trying to see an exoplanet directly is like trying to see a firefly next to a searchlight from miles away.

Instead of looking for planets directly, we look for their effects on their host stars.

Two Main Methods

We’ll focus on the two most successful techniques:

Radial velocity (Doppler): Planet’s gravity makes star wobble; we see periodic Doppler shifts (L10 recap)

Transit method: Planet crosses in front of star; we see periodic brightness dips

Radial Velocity — Recap from L10

The Stellar Wobble

From L10: A planet orbiting a star causes the star to wobble around the system’s center of mass. This wobble creates a periodic Doppler shift in the star’s spectral lines.

- Star moves toward us → blueshift

- Star moves away → redshift

- Pattern repeats with planet’s orbital period

What We Learn

| Observable | What It Tells Us |

|---|---|

| Period of velocity variation | Orbital period (→ distance via Kepler III) |

| Amplitude of velocity variation | Minimum planet mass |

| Shape of velocity curve | Orbital eccentricity |

Limitation: We measure only minimum mass. If the orbit is tilted relative to our line of sight, some of the motion is transverse and doesn’t create Doppler shift. We see \(M_{\text{planet}} \sin i\), where \(i\) is the orbital inclination.

Transit Method — New Technique

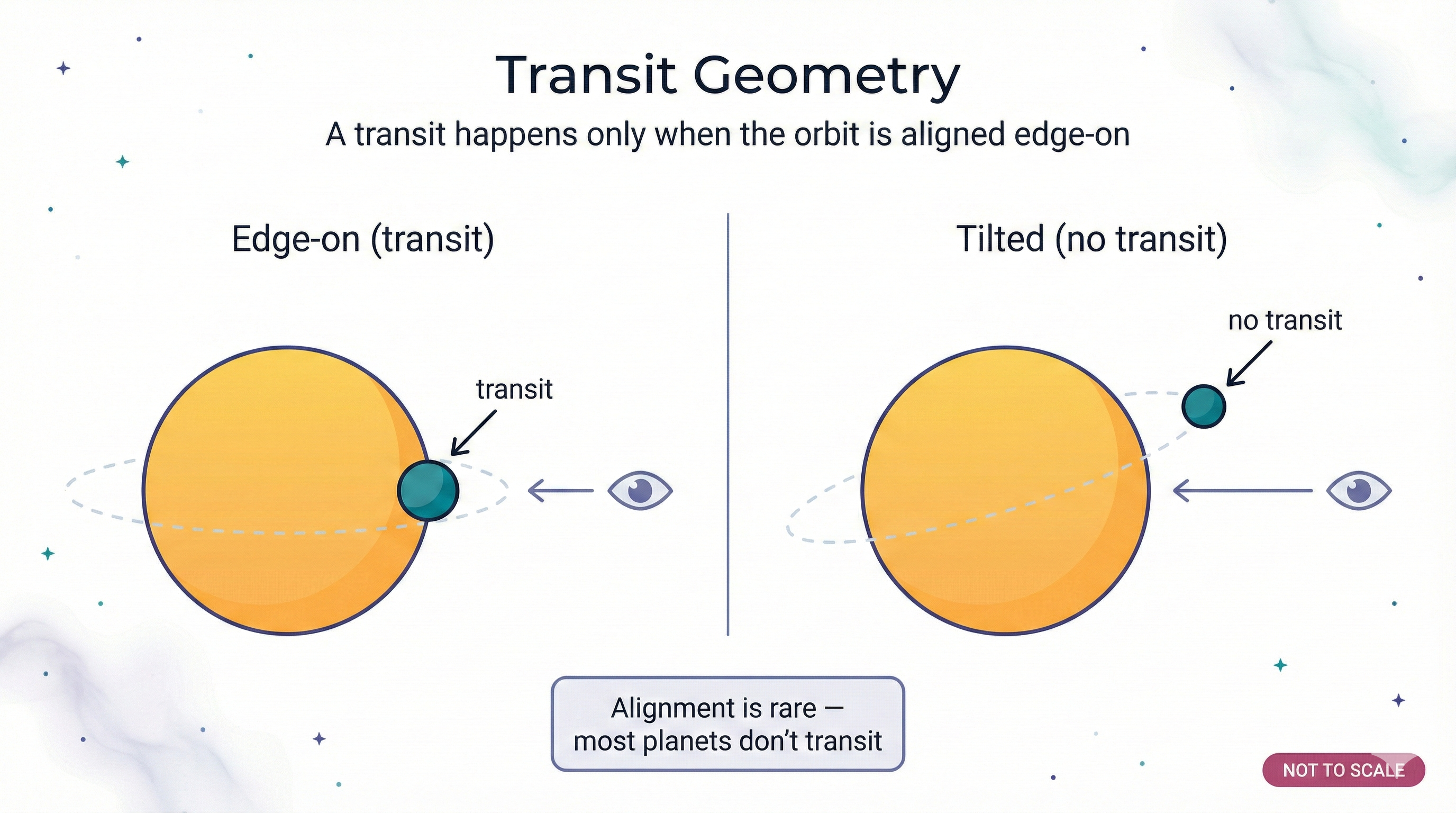

The Basic Idea

When a planet passes in front of its star (from our perspective), it blocks a tiny fraction of the starlight. This creates a dip in brightness that repeats each orbit.

What to notice: transits require a lucky alignment — we only see a transit when the orbit is edge-on, so most planets do not transit from our viewpoint. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

Remember from L4: Eclipses only happen when the Moon crosses the plane of Earth’s orbit (the ecliptic). Most months, the Moon passes above or below the Sun and no eclipse occurs.

The same geometry applies to exoplanet transits:

- We only see a transit if the planet’s orbit is edge-on to our line of sight

- Most exoplanets DON’T transit — their orbits are tilted relative to us

- Transit probability: roughly \(R_{\text{star}}/a\) (larger star or closer planet → more likely)

This means transit surveys miss most planets, but the ones they find are gold: we know exactly how the orbit is tilted (edge-on)!

Selection effect: Because transit probability scales as \(R_*/a\), transit surveys are biased toward close-in planets with short orbital periods. Hot Jupiters were the first transiting exoplanets discovered for exactly this reason — they’re big and close to their stars.

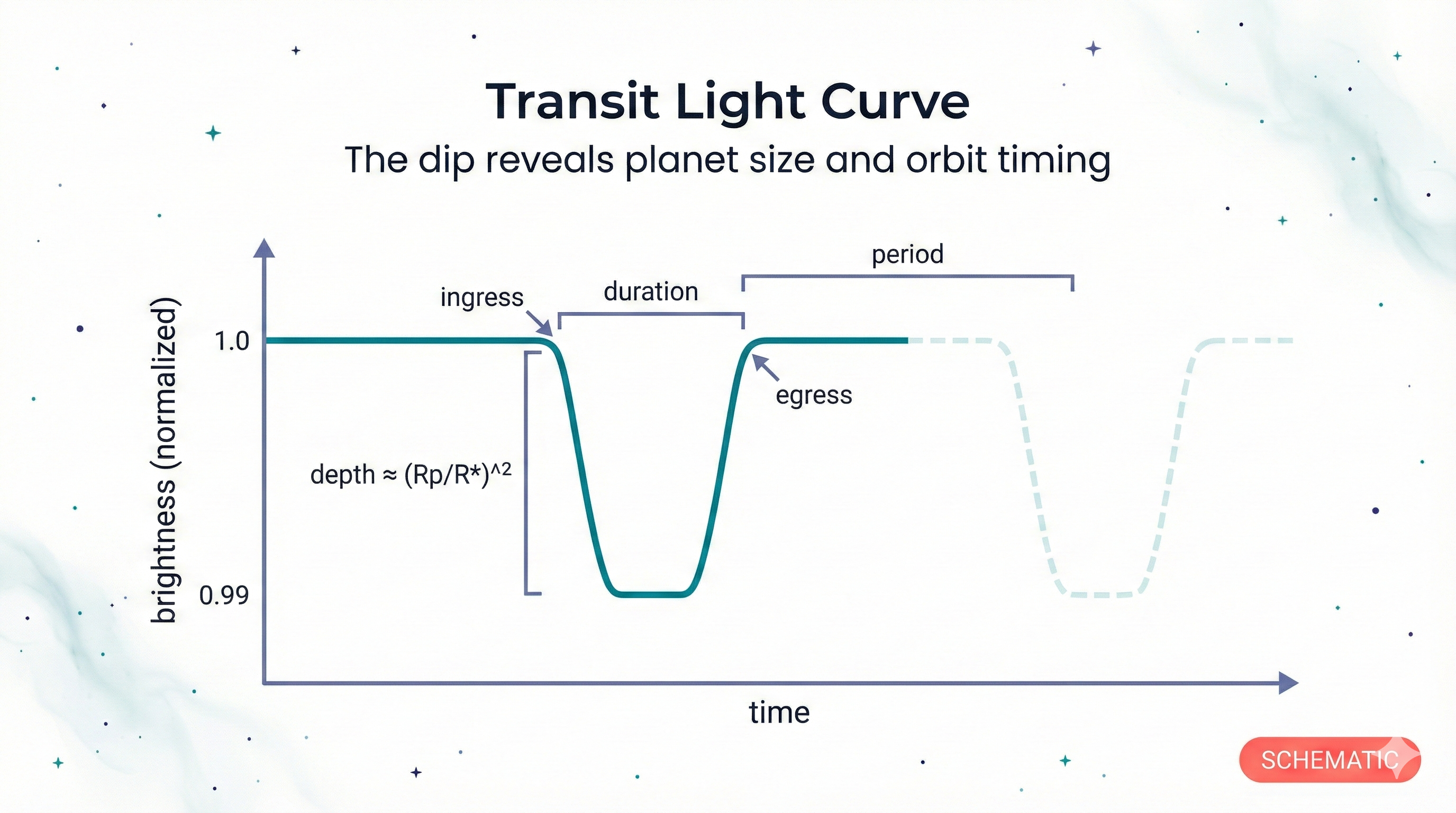

The Transit Light Curve

What to notice: the dip depth sets planet size (≈ (Rp/R*)²) and the timing between dips sets the orbital period. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

What We Learn from Transits

| Observable | What It Tells Us |

|---|---|

| Transit depth | Planet radius: depth ≈ \((R_p/R_*)^2\) |

| Transit duration | Orbital distance (combined with period, stellar mass, and transit geometry) |

| Orbital period | Time between transits |

| Orbital inclination | Must be nearly edge-on (~90°) to transit |

Worked Example: How Big Is the Planet?

Problem: A star’s brightness drops by 1% during transit. If the star is Sun-sized (\(R_* = R_☉\)), how big is the planet?

Solution:

The transit depth is the fraction of starlight blocked:

\[\text{depth} = \left(\frac{R_p}{R_*}\right)^2 = 0.01\]

Solving for planet radius:

\[\frac{R_p}{R_*} = \sqrt{0.01} = 0.1\]

\[R_p = 0.1 \times R_☉ = 0.1 \times 696{,}000 \text{ km} = 69{,}600 \text{ km}\]

This is almost exactly Jupiter’s radius (71,500 km). A 1% dip indicates a Jupiter-sized planet!

An Earth-sized planet transiting a Sun-sized star would produce what transit depth? (Earth’s radius is ~1% of the Sun’s radius)

- 1%

- 0.1%

- 0.01%

- 0.001%

C) 0.01%. Transit depth = \((R_p/R_*)^2 = (0.01)^2 = 0.0001 = 0.01\%\). Earth-sized planets are MUCH harder to detect than Jupiter-sized planets! The Kepler and TESS missions had to achieve incredible photometric precision to find them.

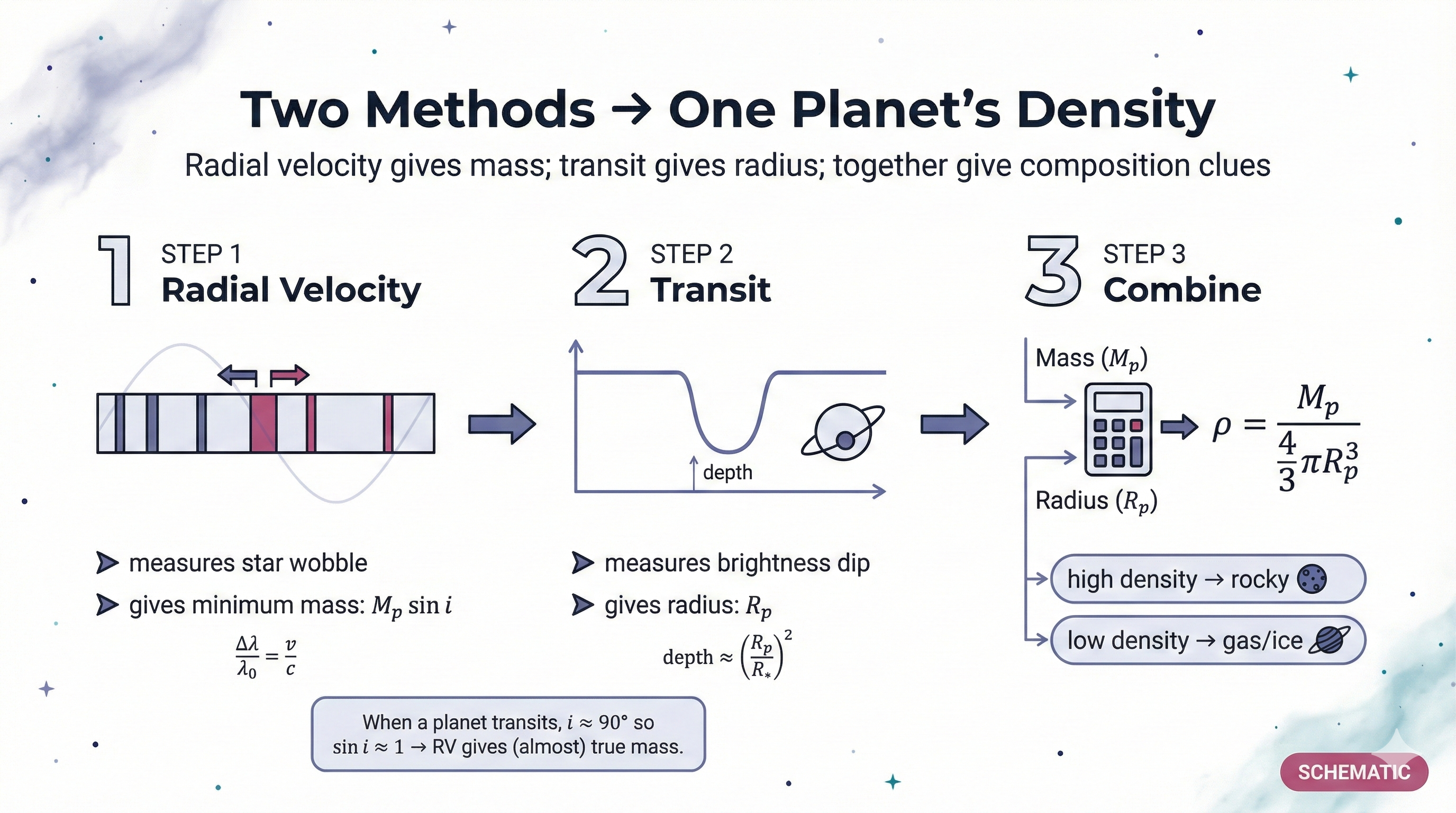

Combining Methods — Density and Composition

The Power of Combining RV + Transit

When a planet both transits and shows radial velocity variations, we hit the jackpot:

| Method | What It Gives Us |

|---|---|

| Transit | Planet radius (\(R_p\)) |

| Radial velocity | Planet mass (\(M_p\)) — and since it transits, \(\sin i \approx 1\), so we get TRUE mass |

What to notice: radial velocity gives planet mass (or minimum mass), transit gives radius; together they give density — a first clue to rocky vs gas/ice composition. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

With both mass and radius:

\[\text{Density} = \frac{M_p}{\frac{4}{3}\pi R_p^3}\]

What Density Tells Us

| Density | Composition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| ~5.5 g/cm³ | Rocky (iron + silicate) | Earth |

| ~1.3 g/cm³ | Gas giant (H/He) | Jupiter |

| ~2-3 g/cm³ | Water world? Mini-Neptune? | Some super-Earths |

Intermediate densities (2–4 g/cm³) can be degenerate: different mixtures of rock, water, and gas can produce the same bulk density. Density is a strong clue to composition, but not a complete answer — additional constraints (atmospheric spectra, formation models) help break the degeneracy.

Density distinguishes rocky planets (potential for habitability) from gas/ice worlds (probably not habitable at the surface).

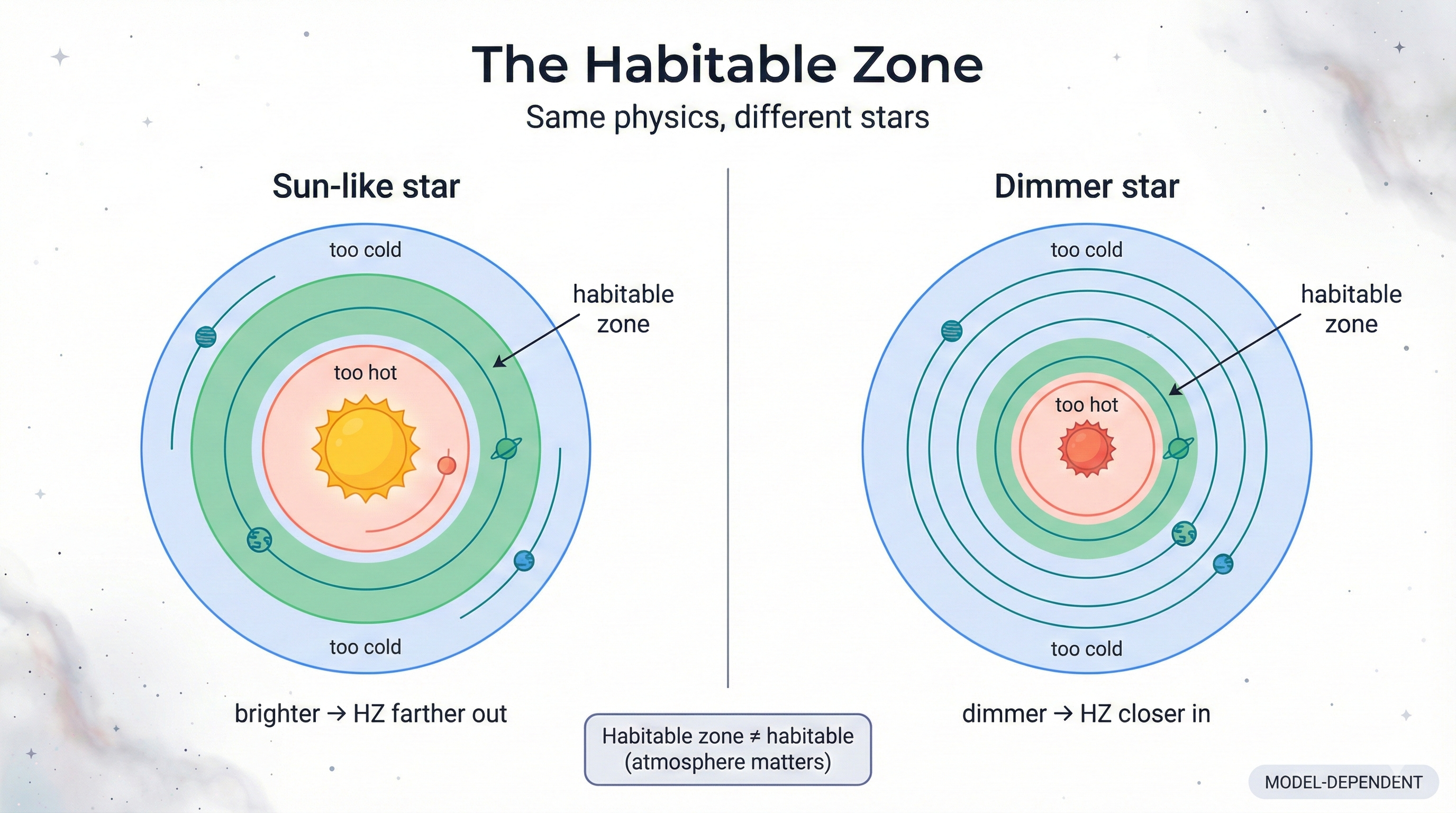

The Habitable Zone

The Goldilocks Zone

The habitable zone is the range of distances from a star where liquid water could exist on a planet’s surface — not too hot (water boils), not too cold (water freezes).

What to notice: habitable zone distance depends on stellar luminosity — brighter stars push the zone outward, dimmer stars pull it inward — and the zone is not a guarantee of habitability. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini — schematic))

What Determines the Habitable Zone?

The habitable zone depends on:

Stellar luminosity: More luminous star → HZ is farther out (Stefan-Boltzmann callback!)

Atmospheric greenhouse effect: Strong greenhouse → HZ extends farther out

Planetary albedo: More reflective → needs to be closer to absorb enough heat

For the Sun (approximate, model-dependent):

- Inner edge: ~0.95–0.99 AU (Venus is just inside — but runaway greenhouse happened)

- Outer edge: ~1.4–1.7 AU (Mars is near the edge — and had liquid water with a thicker early atmosphere)

These boundaries depend on assumptions about atmospheric composition, cloud feedbacks, and planetary rotation. Different climate models give different estimates — the numbers above span “conservative” to “optimistic” 1-D models.

Habitable Zone ≠ Habitable

Being in the habitable zone doesn’t guarantee a planet is habitable!

Venus is near the inner edge and is a 735 K hellscape. Mars is near the outer edge and is a frozen desert.

Habitability depends on:

- Having an atmosphere (and keeping it)

- The right greenhouse effect

- Liquid water on the surface

- Perhaps: magnetic field, plate tectonics, and more

The habitable zone is a starting point, not a guarantee.

If a star is 4× as luminous as the Sun, how does its habitable zone compare?

- Same location as the Sun’s

- Closer to the star

- Farther from the star

- There is no habitable zone

C) Farther from the star. A more luminous star delivers more energy, so planets at Earth’s distance would be too hot. The habitable zone moves outward by a factor of \(\sqrt{4} = 2\). If the Sun’s HZ is at ~1 AU, this star’s HZ would be at ~2 AU.

Planetary Climates:

- Equilibrium temperature depends on distance from Sun and albedo

- Greenhouse effect: Atmosphere absorbs IR → surface warms above equilibrium

- Venus: Runaway greenhouse → 735 K hellscape

- Mars: Too little atmosphere → 218 K frozen desert

- Earth: Moderate greenhouse, liquid water, life — adding CO₂ shifts the balance

Exoplanet Detection:

- Radial velocity: Star wobble → minimum planet mass

- Transit: Brightness dip → planet radius (depth = \((R_p/R_*)^2\))

- Combined: Mass + radius → density → rocky vs. gaseous

- Habitable zone: Where liquid water could exist (depends on stellar luminosity)

Practice Problems

Core (do these first)

1. Greenhouse Calculation: Earth’s equilibrium temperature is ~255 K, but its actual surface temperature is ~288 K. Calculate the greenhouse warming effect in Kelvin. Compare to Venus (T_eq ≈ 230 K, T_actual = 735 K).

2. Transit Depth: A planet with radius 2× Earth’s transits a Sun-like star. What is the transit depth? By what factor is this easier to detect than an Earth-sized planet?

3. Habitable Zone Scaling: A star has luminosity 1/4 that of the Sun. Where is its habitable zone compared to the Sun’s? (Hint: Consider the Stefan-Boltzmann law and equilibrium temperature.)

4. Detection Methods: You detect a planet via both radial velocity (star wobbles at 100 m/s) and transit (1% depth). What two properties can you now calculate that you couldn’t with just one method?

Challenge

5. Venus’s History: Explain in your own words how Venus went from possibly habitable to its current state. Include the role of distance from Sun, water vapor feedback, and CO₂ accumulation.

6. Density Interpretation: You discover a planet with the same mass as Neptune but the same radius as Earth. Calculate its density and compare to Earth (5.5 g/cm³) and Neptune (1.6 g/cm³). What might this planet be made of?

Glossary

No glossary terms for lecture 12.