The Sky Is a Map

Lecture 3 Reading Companion

The sky is a direction-finder, not a depth-gauge. Every position on the sky is an angle, not a distance — and understanding this geometric framework unlocks seasons, eclipses, and the entire toolbox of positional astronomy.

This page is both (1) the assigned reading and (2) your reference manual for celestial geometry. You should expect to come back to it multiple times — before lecture, after lecture, while doing practice problems and assignments, and studying for exams.

Default expectation (best): Read the whole page before class (including Check Yourself). Then return to it later when you work the Practice Problems.

If you’re short on time before class (~15 min): Do the Musts for today so you can participate now — then come back and finish the rest.

- Musts for today: The Big Idea • The Celestial Sphere • Seasons: Tilt, Not Distance • Angular Size Basics

- Non-negotiable: Stop and answer every Check Yourself question you encounter in these sections (don’t just read past them).

Skim now, read carefully later: The Deep Dives and Demo Explorations. Skimming is a preview — you’ll get much more from it after lecture.

Demo Explorations (do these!): This reading integrates two interactive demos. Work through them at your own pace — they’re designed to build intuition that words alone can’t provide.

Reassurance: This is geometry, not memorization. If you can draw it, you can understand it. Your goal is building mental models, not cramming vocabulary. Look for the ✏️ Sketch It prompts throughout — they’ll help you lock in the geometry.

The Problem: Astronomy Without Depth Perception

Look up at the night sky. You see points of light scattered across a dark dome. Some are brighter, some dimmer. Some cluster together in familiar patterns we call constellations.

Here’s the fundamental problem: you have no depth perception.

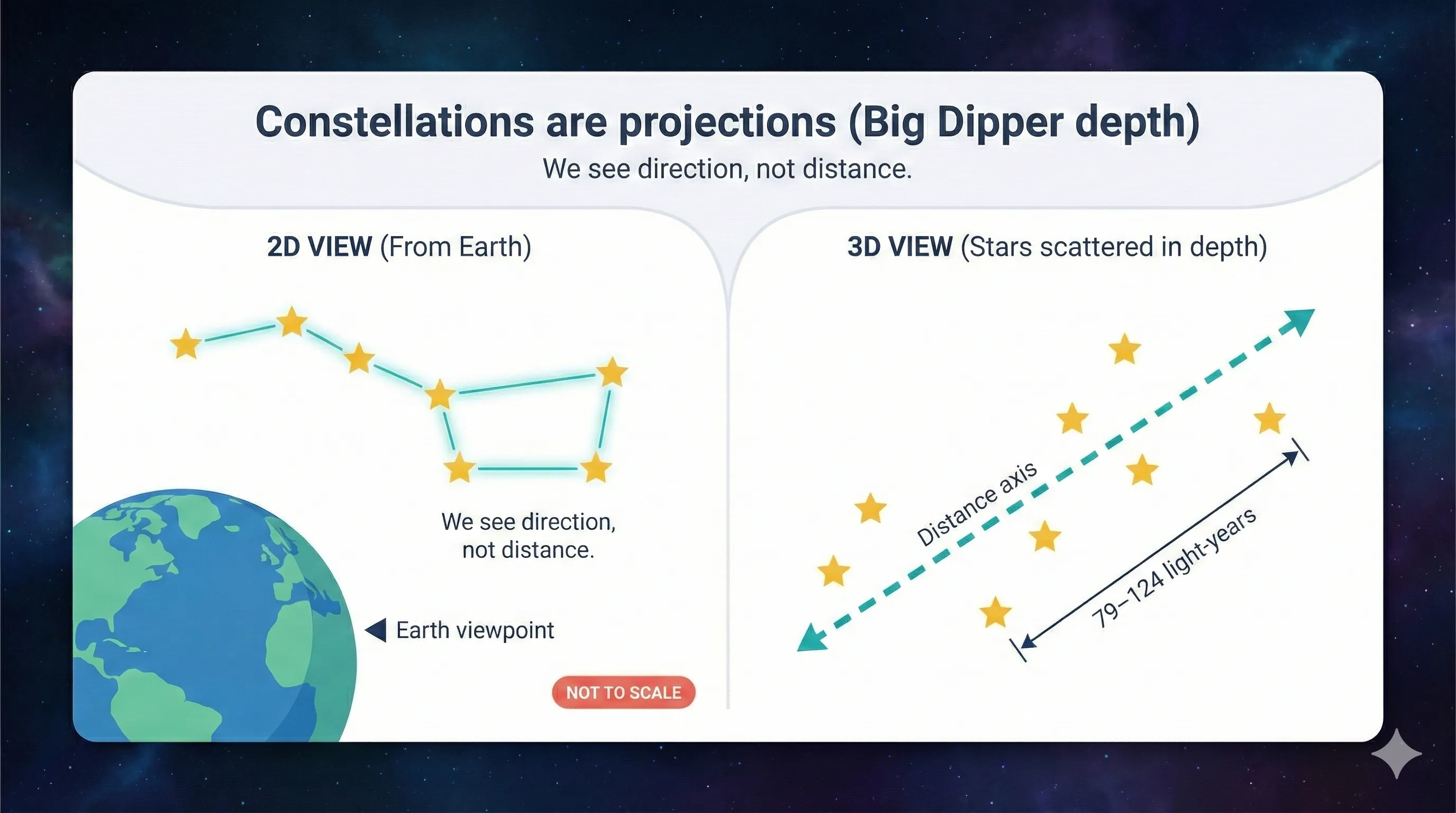

Your eyes can’t tell you whether a star is close and dim or far and luminous. The Big Dipper’s seven stars look like they belong together — like friends sitting around a cosmic campfire. But they’re not. They’re scattered at wildly different distances, from 79 to 124 light-years away. They just happen to lie along similar directions as seen from Earth.

What to notice: Constellations are patterns on the sky, not physical groupings; stars can be at very different distances. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini))

Several Big Dipper stars actually share a common motion through space (a “moving group”), suggesting they formed together. But the dipper pattern is still a projection — from a different vantage point in the galaxy, those same stars would form a completely different shape.

This isn’t a limitation — it’s a starting point. The sky gives us directions by default. Measuring distances requires extra work (remember the cosmic distance ladder from Lecture 1). Today, we embrace what the sky naturally provides: a coordinate system for pointing at things.

Stars in a constellation are physically close together in space.

- True

- False

B) False. Stars in a constellation appear close together on the sky because they lie along similar directions as seen from Earth not because they’re physically near each other. The stars of Orion, for example, range from about 250 to over 2,000 light-years away. Constellations are patterns of projection, not physical associations.

Constellation: A named pattern of stars on the sky. A constellation is defined by directions (angles), not by stars being physically close together in space.

The Celestial Sphere: A Map of Directions

Why a Sphere?

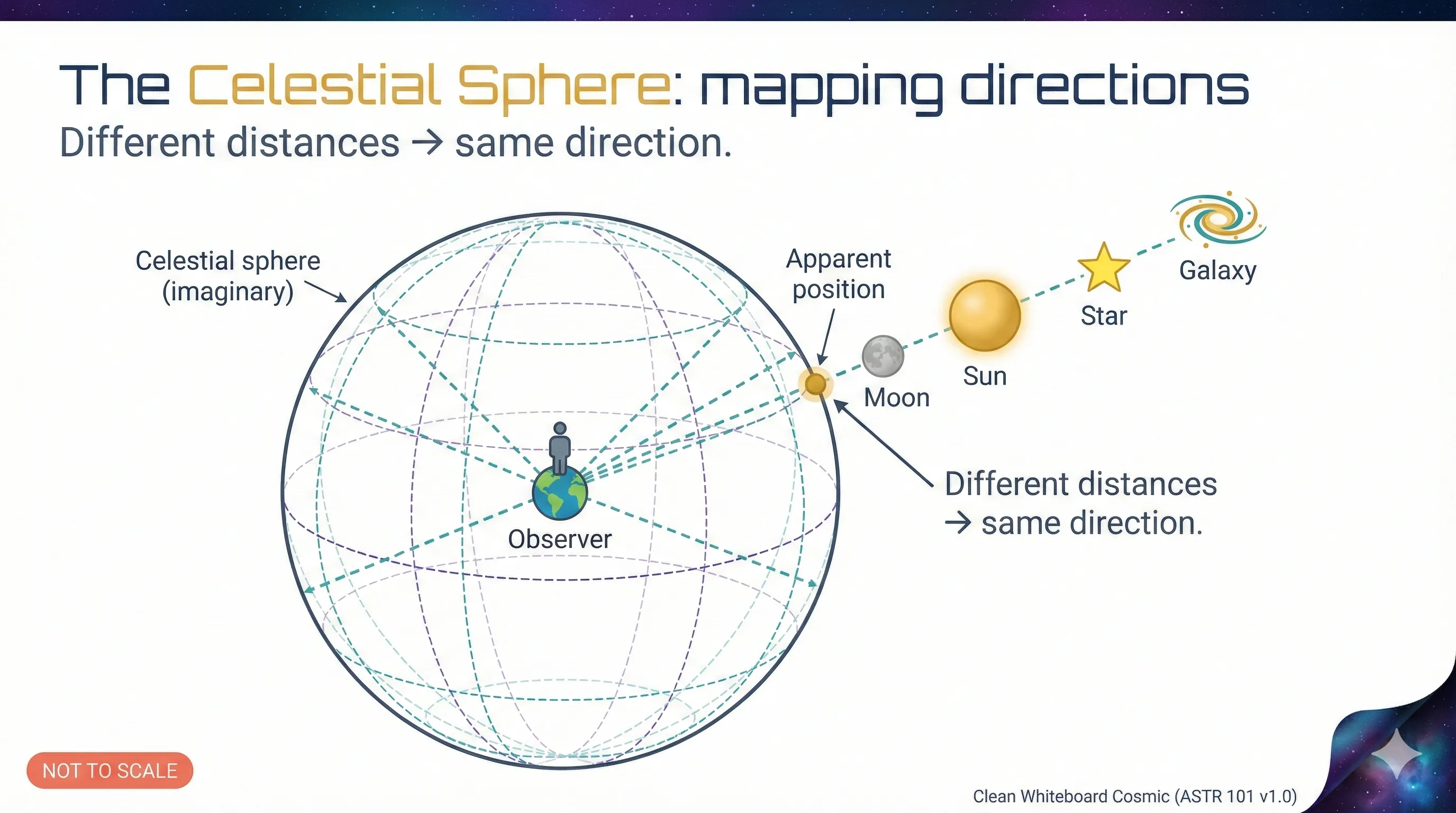

Imagine you’re standing at the center of a vast, transparent globe. Every star, planet, and galaxy can be located by pointing in some direction from where you stand. Those directions can be mapped onto the inside surface of the sphere.

This imaginary sphere is the celestial sphere — and it’s one of astronomy’s oldest and most useful conceptual tools.

Celestial sphere: An imaginary sphere of arbitrary radius centered on the observer, onto which all celestial objects are projected. It’s a coordinate system for directions, not a claim about where things actually are.

Celestial sphere directions and local sky coordinates (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini))

Key insight: The celestial sphere doesn’t represent where things are — it represents where to look. It’s a direction-finder, not a distance-finder.

The celestial sphere tells us:

- How far away celestial objects are

- What direction to look to find celestial objects

- The physical size of stars

- The age of the universe

B) What direction to look to find celestial objects. The celestial sphere is purely a coordinate system for directions. Distance, size, and age must be inferred through other methods (remember: those aren’t direct observables!).

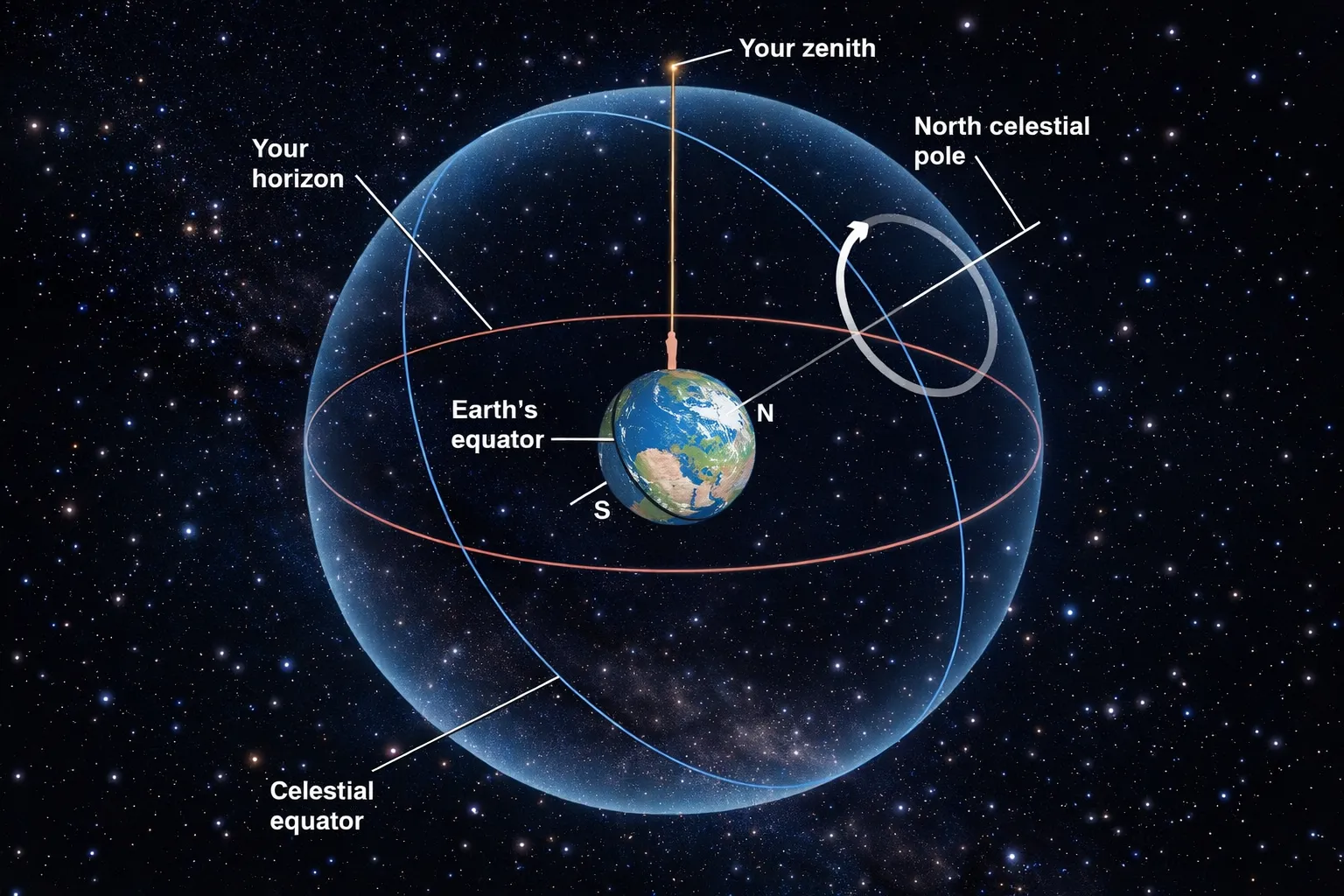

Key Reference Points and Circles

The celestial sphere has special points and circles that help us navigate. Here are the essentials for this course:

Essential Reference Points:

| Point | Definition | What It Corresponds To |

|---|---|---|

| Celestial poles | Points where Earth’s rotation axis, extended, pierces the celestial sphere | Earth’s geographic poles projected onto the sky |

| Zenith | The point directly overhead for any observer | Your local “up” direction |

Essential Reference Circles:

| Circle | Definition | What It Corresponds To |

|---|---|---|

| Celestial equator | Earth’s equator projected onto the celestial sphere | Divides northern and southern celestial hemispheres |

| Horizon | The circle where sky meets ground for an observer | Depends on your location |

| Ecliptic | The Sun’s apparent yearly path across the sky | Earth’s orbital plane projected onto the sky |

Essential Coordinates (for this course):

| Coordinate | What It Means | Earth Analog |

|---|---|---|

| Declination (Dec) | Celestial latitude: angle north/south of the celestial equator (−90° to +90°) | Latitude |

| Right ascension (RA) | Celestial longitude: position along the celestial equator measured from a fixed zero point; often given in hours (0–24h) | Longitude |

RA in hours: 24 hours = 360°, so 1 hour = 15°. Astronomers often use hours for RA because the sky appears to rotate once per day.

Great circle: Any circle on a sphere whose center coincides with the center of the sphere. The celestial equator, ecliptic, and horizon are all great circles. They divide the celestial sphere into equal halves.

Reference points and great circles on the celestial sphere (Credit: (A. Rosen/ChatGPT))

Key geometry clarification: Zenith is a direction (straight up from where you stand). North is a compass direction along your local horizon. They are not the same axis — you can point north while looking straight ahead, but zenith is straight up.

Draw Earth as a circle. Put a stick-figure observer on Earth’s surface.

- Draw Earth’s rotation axis through the globe and label North Pole and South Pole.

- Around Earth, draw a larger circle representing the celestial sphere.

- Extend the rotation axis until it hits the celestial sphere in two points. Label them north celestial pole and south celestial pole.

- At the observer, draw an arrow straight out from Earth’s surface and label it zenith (your local “up”).

- Through the observer, draw a line tangent to Earth (your local “flat ground” direction) and sketch the horizon circle on the celestial sphere.

- Finally, mark north on the horizon: it is a direction along the horizon (toward Earth’s geographic north), not the same as zenith.

If you can draw this, you can keep “up,” “north,” and “celestial poles” straight in your head.

If you want to do serious sky navigation or use star charts, these additional terms are useful:

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Nadir | The point directly below the observer (opposite the zenith) |

| Meridian | The great circle passing through zenith, nadir, and celestial poles — your local north-south line |

| Hour angle | How far west an object is from the meridian |

These won’t appear on exams, but they’re the full toolkit for positional astronomy.

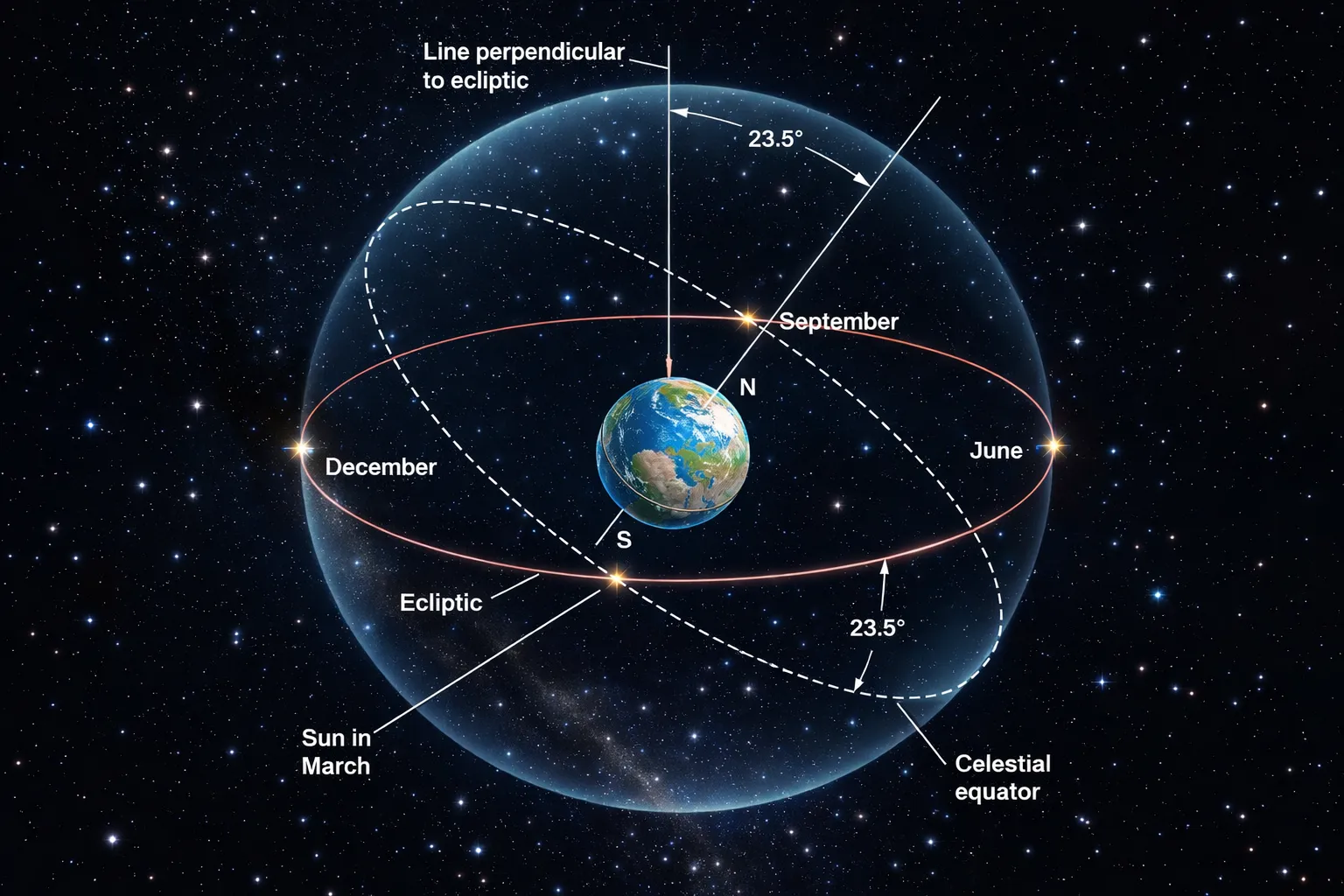

Two Circles That Matter: Celestial Equator vs. Ecliptic

For understanding seasons and eclipses, two circles are essential:

The Celestial Equator is Earth’s equator projected onto the sky. If you stood on Earth’s equator, your zenith would lie on the celestial equator. This circle is defined by Earth’s rotation — it’s perpendicular to Earth’s spin axis.

The Ecliptic is the Sun’s apparent yearly path across the sky. As Earth orbits the Sun, the Sun appears to drift eastward against the background stars, completing one full circuit per year. This path is the ecliptic — and it’s defined by Earth’s orbit.

The ecliptic on the celestial sphere (Credit: (A. Rosen/ChatGPT))

The crucial point: These two circles are not aligned. They’re tilted relative to each other by about 23.5° — and this tilt is the entire reason we have seasons.

Ecliptic: The apparent path of the Sun across the celestial sphere over the course of a year, corresponding to the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun.

Draw a circle (the celestial equator). Now draw another circle tilted 23.5° relative to the first (the ecliptic). Mark the two points where they intersect.

Label: What happens at those intersection points? (Hint: The Sun is on the celestial equator at these moments.)

The ecliptic is:

- The path the Moon takes across the sky each night

- The Sun’s apparent path across the sky over the course of a year

- The same as the celestial equator

- The edge of Earth’s shadow

B) The Sun’s apparent path across the sky over the course of a year. As Earth orbits the Sun, the Sun appears to move against the background stars, tracing out a great circle called the ecliptic. This corresponds to the plane of Earth’s orbit. The ecliptic is tilted 23.5° relative to the celestial equator — that’s why seasons exist.

The celestial equator and ecliptic are tilted relative to each other because:

- The Moon pulls on Earth

- Earth’s rotation axis is tilted relative to its orbital plane

- The Sun wobbles

- Stars aren’t evenly distributed

B) Earth’s rotation axis is tilted relative to its orbital plane. Earth’s equator is perpendicular to its rotation axis. Earth’s orbit defines the ecliptic plane. Since the rotation axis is tilted 23.5° from the perpendicular to the orbital plane, the celestial equator and ecliptic are tilted by the same amount.

Two Motions, Two Time Scales

A common source of confusion: the Sun moves across the sky in two different ways, on two different time scales.

| Motion | Cause | Time Scale | What You See |

|---|---|---|---|

| Daily arc | Earth’s rotation | 24 hours | Sun rises in east, arcs across sky, sets in west* |

| Yearly drift | Earth’s orbit | 365.25 days | Sun slowly slides eastward along the ecliptic, visiting different constellations |

(Near the poles, there are parts of the year when the Sun doesn’t rise or doesn’t set.)

The daily arc is why the Sun is up during the day. The yearly drift is why the Sun’s noon altitude changes with the seasons.

This distinction matters: when we talk about the Sun’s position “changing with the seasons,” we mean its position along the ecliptic (the yearly drift), not its daily east-to-west motion.

The time it takes Earth to orbit the Sun (the year that keeps the seasons lined up) is not an exact whole number of days. If our calendar always had exactly 365 days, the dates of the solstices and equinoxes would slowly drift through the calendar.

The fix: We add leap days to keep the calendar aligned with Earth’s orbit and the seasons.

The rule (Gregorian calendar): - Most years divisible by 4 are leap years (we add February 29). - Century years (divisible by 100) are not leap years… - …unless they are also divisible by 400 (then they are leap years).

This keeps the calendar much better synchronized with Earth’s seasonal cycle over long times.

Seasons: Tilt, Not Distance

The Misconception That Won’t Die

Quick — what causes the seasons?

If you said “Earth is closer to the Sun in summer,” you’re in good company. This is one of the most persistent misconceptions in astronomy education. Surveys consistently show that many adults, including college students, hold this belief.

It’s a common and very reasonable first guess — but it doesn’t match what we observe.

Here’s the proof: When it’s summer in the Northern Hemisphere, it’s winter in the Southern Hemisphere. If distance caused seasons, both hemispheres would experience summer at the same time — when Earth is closest to the Sun.

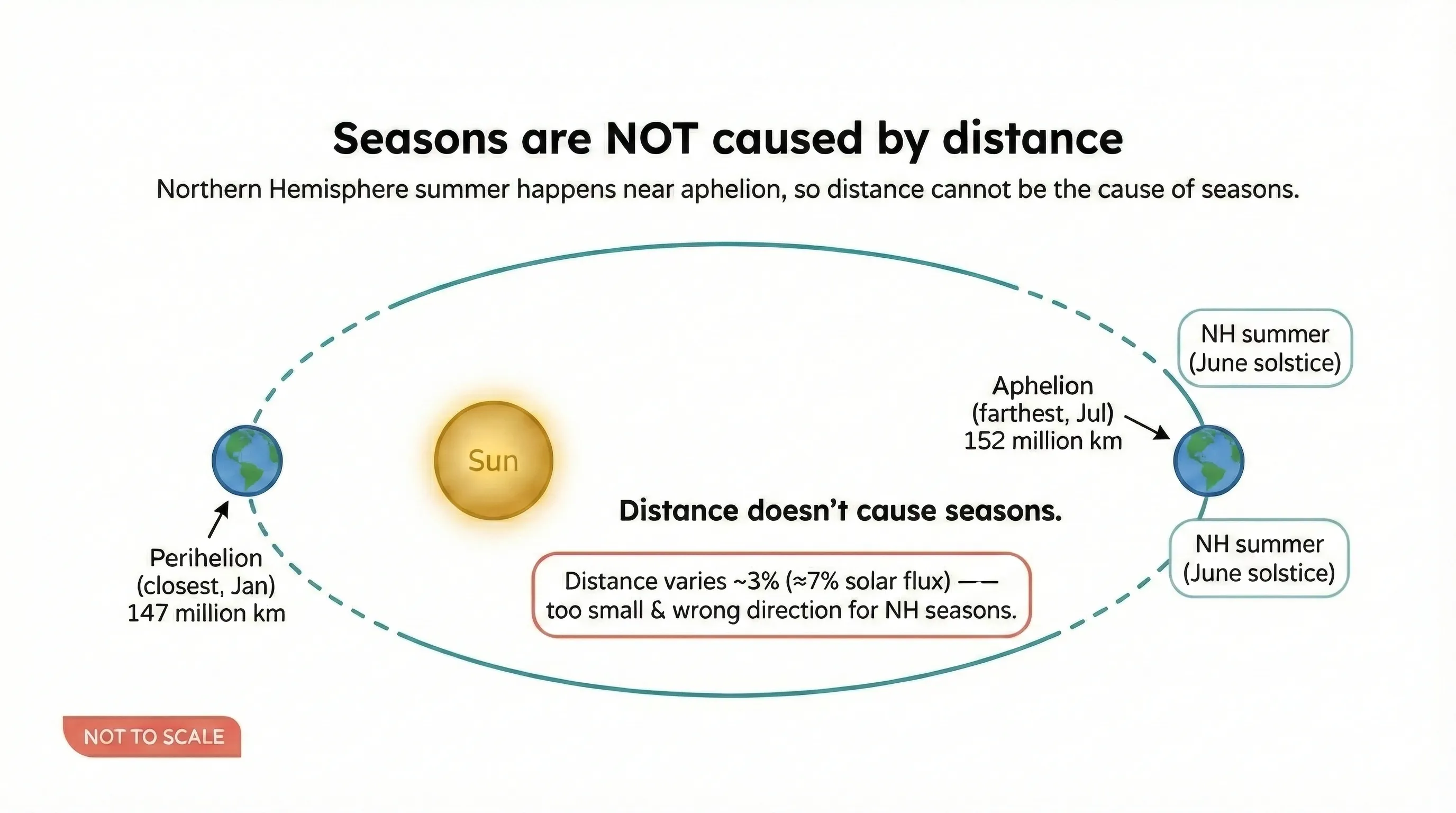

What to notice: Seasons are not caused by Earth–Sun distance; tilt changes the Sun’s angle and day length. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Gemini))

The numbers: Earth’s distance from the Sun varies by only about 3% over the year — from 147 million km at perihelion (closest, in January) to 152 million km at aphelion (farthest, in July). This 3% variation affects how much total energy Earth receives by about 7% — far too small to explain the dramatic temperature swings of seasons, and in the wrong direction for the Northern Hemisphere anyway.

Because perihelion happens during Southern Hemisphere summer, the SH receives slightly higher solar flux then. In an Earth-without-oceans thought experiment, that would make SH summers a bit more intense. On real Earth, the distribution of oceans and land dominates regional climate patterns, so this effect is subtle. The 7% difference is real — it just isn’t what causes seasons.

If Earth’s distance from the Sun caused the seasons, what would we observe?

- The Northern and Southern Hemispheres would have opposite seasons

- Both hemispheres would have summer at the same time

- There would be no seasons at all

- Seasons would depend on altitude, not latitude

B) Both hemispheres would have summer at the same time. If distance were the cause, then when Earth was closest to the Sun, the entire planet would receive more energy and both hemispheres would warm up together. The fact that hemispheres have opposite seasons proves distance isn’t the mechanism.

The Real Mechanism: Geometry of Illumination

Seasons result from two geometric effects, both caused by Earth’s 23.5° axial tilt:

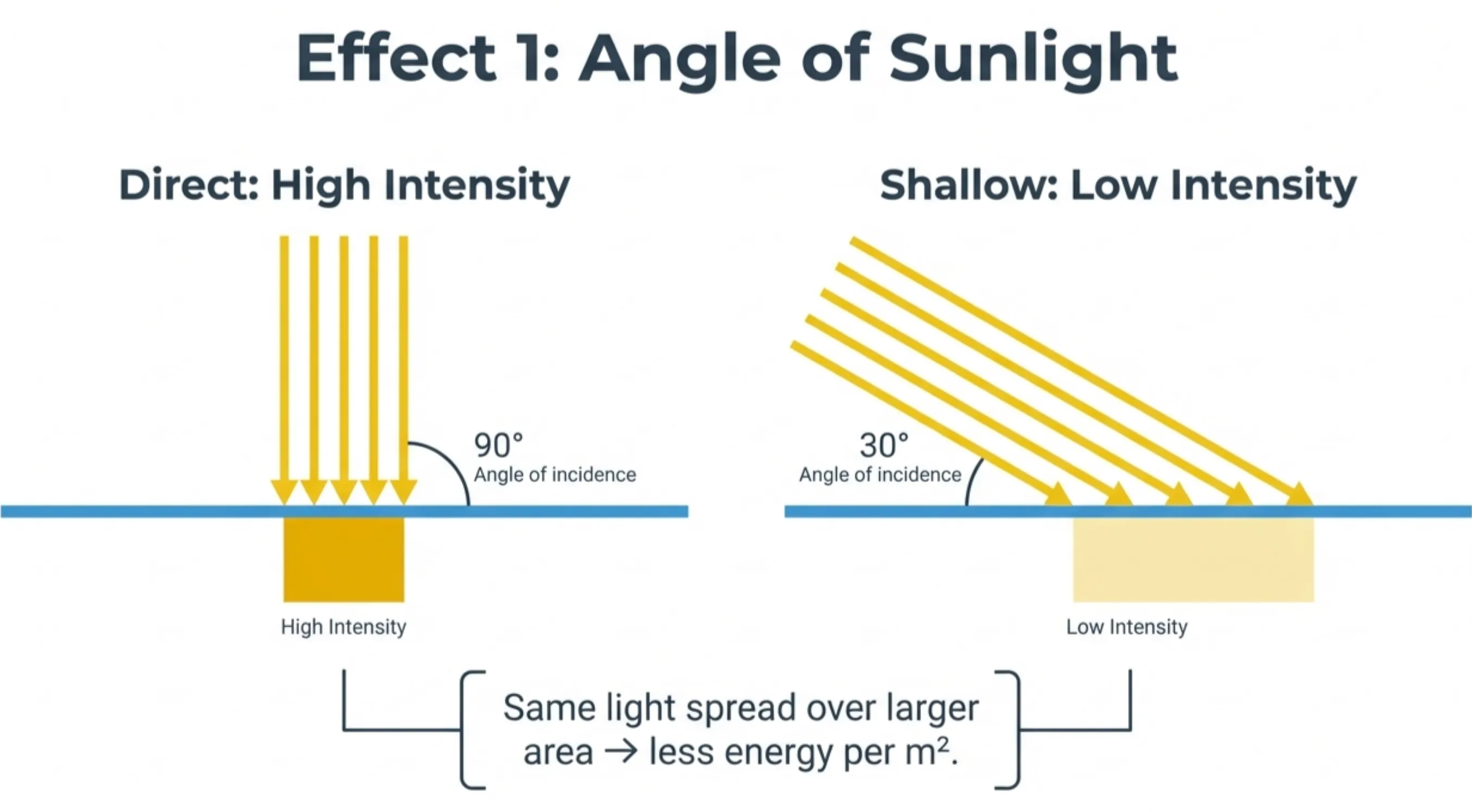

Effect 1: Sunlight Angle

When the Sun is higher in the sky, its rays hit the ground more directly. When the Sun is lower, the same amount of light spreads over a larger area.

Think of it this way: shine a flashlight straight down on a table — you get a bright circle. Now tilt the flashlight at an angle — the same light spreads into an oval, covering more area but with less intensity per square meter.

Effect 1: Sunlight angle changes energy per area (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

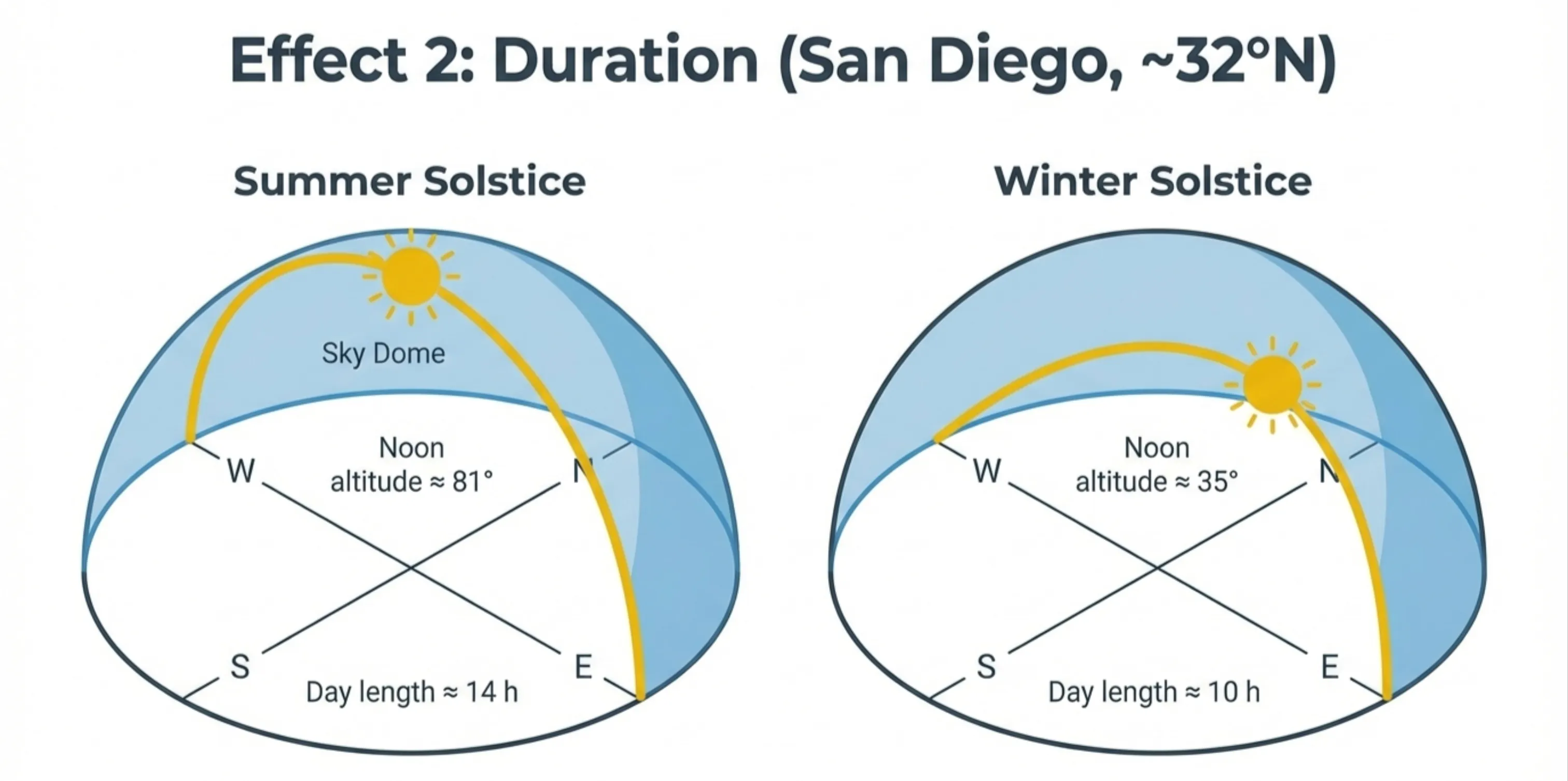

Effect 2: Day Length

When your hemisphere is tilted toward the Sun, the Sun takes a longer path across your sky. More hours of daylight means more hours of heating.

At the summer solstice in San Diego (~32°N latitude): - The Sun is up for about 14 hours - It reaches a maximum altitude of about 81° above the southern horizon

At the winter solstice: - The Sun is up for only about 10 hours - It reaches a maximum altitude of only about 35°

That’s 4 extra hours of daylight AND much more direct sunlight. The combination is powerful.

Effect 2: Day length and Sun path change seasonally (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Seasons are fundamentally about how much solar energy per square meter your location receives over a day. Tilt changes that through sun angle (how concentrated the rays are) and day length (how many hours of heating).

The hottest and coldest temperatures usually occur weeks after the solstices because Earth’s surface and oceans take time to warm up and cool down (“thermal inertia”).

Draw Earth with its tilted axis. Add parallel rays of sunlight coming from the right. Show how the Northern Hemisphere receives more direct sunlight when tilted toward the Sun, and less direct sunlight when tilted away.

Label: Where is the terminator (day/night boundary)? How does its position explain different day lengths?

During summer in your hemisphere, the Sun:

- Is closer to Earth and appears larger

- Rises and sets at the same points as in winter, just brighter

- Takes a higher, longer path across the sky

- Moves faster across the sky

C) Takes a higher, longer path across the sky. The two effects that cause warmer summers are: (1) higher Sun angle, concentrating energy on less surface area, and (2) longer day length, providing more hours of heating. Both result from your hemisphere being tilted toward the Sun.

🔭 Demo Exploration: Seasons

Open the Seasons Demo: astrobytes-edu.github.io/astr101-sp26/demos/seasons/

This interactive demo lets you see why tilt — not distance — causes seasons. You’ll observe how day length, Sun altitude, and Earth-Sun distance change throughout the year.

What you’ll see in the demo: - Season Presets: Jump to solstices and equinoxes - Readouts: Day Length, Sun Altitude, Earth-Sun Distance for the selected date - Display Overlays: Celestial Equator, Ecliptic, Day/Night Terminator - Observer Latitude: See how seasons differ at different latitudes

Demo Mission 1: Testing the Distance Hypothesis

Predict before you explore: If distance caused seasons, what would you expect to see in the Earth-Sun Distance reading during Northern Hemisphere summer (June)?

Write your prediction here before continuing: _______________

Do this: 1. Click Season Presets and select each season in order: March Equinox → June Solstice → September Equinox → December Solstice 2. For each, record the Earth-Sun Distance reading

| Season | Earth-Sun Distance |

|---|---|

| March Equinox | |

| June Solstice (N. Summer) | |

| September Equinox | |

| December Solstice (N. Winter) |

What did you find? Is Earth closer to the Sun during Northern summer or Northern winter?

Earth is actually farthest from the Sun (aphelion) in early July — during Northern Hemisphere summer! Earth is closest (perihelion) in early January — during Northern winter. This directly contradicts the “distance causes seasons” hypothesis.

The distance varies by only about 3%, which creates about a 7% difference in total solar energy received — nowhere near enough to explain the large temperature differences between seasons.

Claim: Distance cannot be the primary cause of seasons.

Evidence: The demo’s Earth-Sun Distance readout shows Earth is farthest from the Sun during Northern summer, the opposite of what the distance hypothesis predicts.

Demo Mission 2: The Real Mechanism

Do this: 1. Turn on Display Overlays: Celestial Equator, Ecliptic, and Day/Night Terminator 2. Go to June Solstice and observe the Day/Night Terminator position 3. Go to December Solstice and observe how it changes 4. Record the Day Length and Sun Altitude for both

| Season | Day Length | Sun Altitude |

|---|---|---|

| June Solstice | ||

| December Solstice |

The key question: What changes between June and December that could explain the temperature difference?

In June (Northern summer): - Day length is much longer (more hours of heating) - Sun altitude is much higher (more concentrated energy per square meter)

In December (Northern winter): - Day length is much shorter - Sun altitude is much lower (energy spread over larger area)

Claim: Seasons are caused by the combined effect of changing day length and Sun angle.

Evidence: The demo’s Day Length and Sun Altitude readouts both change dramatically between solstices, while distance barely changes. These geometric effects — not distance — explain seasonal temperature variation.

Demo Mission 3: Latitude Matters

Do this: 1. Stay on June Solstice 2. Change Observer Latitude from the Equator (0°) to mid-latitudes (40°N) to near the pole (66.5°N, the Arctic Circle) 3. Watch what happens to Day Length

| Latitude | Day Length (June Solstice) |

|---|---|

| 0° (Equator) | |

| 40°N | |

| 66.5°N (Arctic Circle) |

What pattern do you see? Why do high-latitude regions experience such extreme seasons?

At higher latitudes, the seasonal variation in day length becomes more extreme: - At the Equator: Day length is nearly 12 hours year-round - At 40°N: Day length varies from about 9 hours (winter) to 15 hours (summer) - At the Arctic Circle: On the summer solstice, the Sun never sets (24-hour day!)

Claim: Higher latitudes experience more extreme seasons because day length variation is greater.

Evidence: The demo’s Day Length readout shows equatorial regions have ~12 hours year-round, while polar regions swing from 0 to 24 hours. This geometric effect of tilt is amplified at high latitudes.

You’ve just demonstrated with the Seasons demo that:

- Earth is closest to the Sun in June, causing Northern summer

- The Sun moves faster in summer, causing longer days

- Axial tilt causes variations in day length and Sun angle that explain seasons

- Distance from the Sun is the primary cause of seasonal temperature changes

C) Axial tilt causes variations in day length and Sun angle that explain seasons. The demo shows that Earth-Sun distance is actually largest during Northern summer, ruling out distance as the cause. Instead, the tilt of Earth’s axis creates two effects: (1) the Sun appears higher in the sky (more concentrated energy), and (2) days are longer (more total hours of heating).

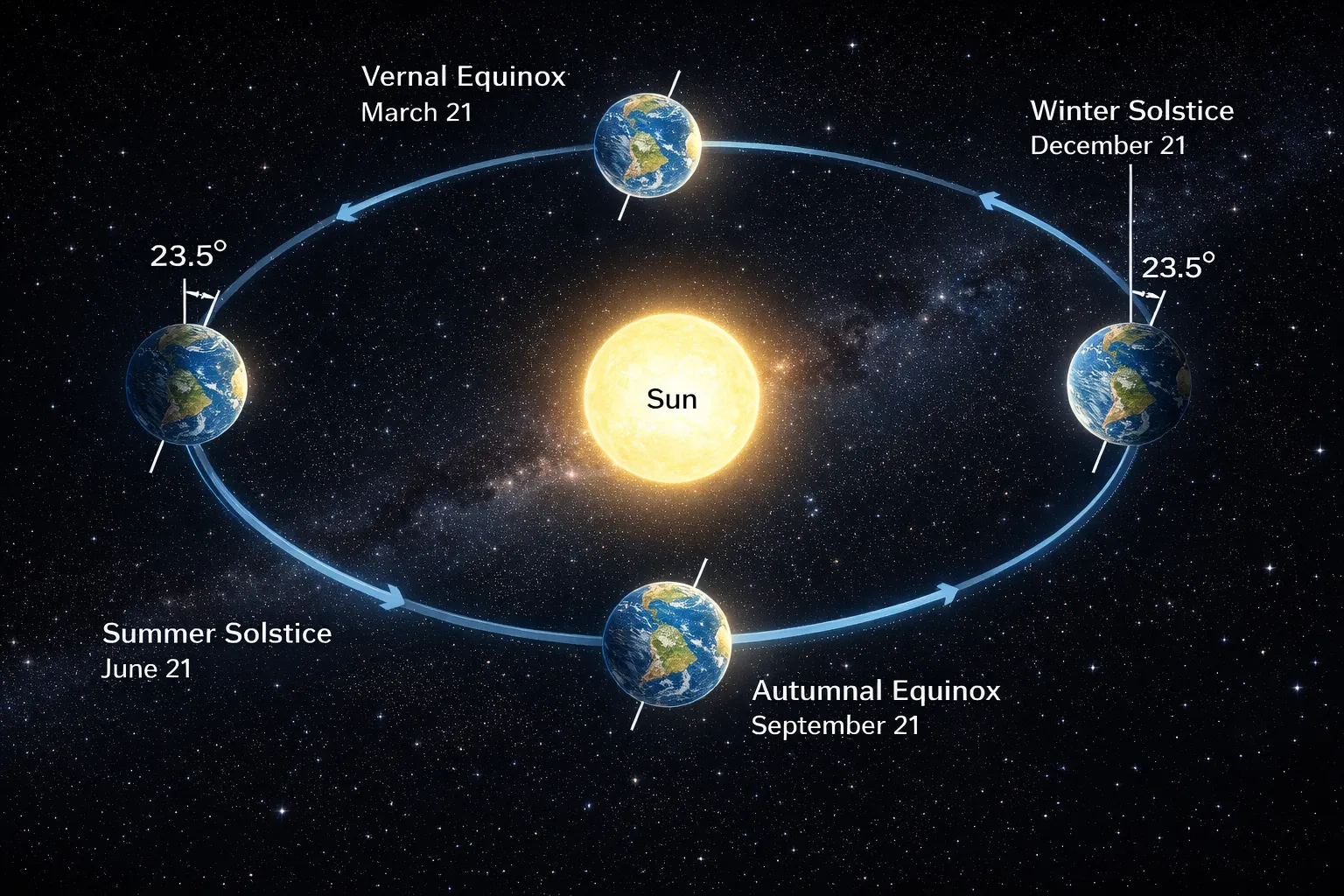

Solstices and Equinoxes: Special Geometry Days

The seasons are marked by four special configurations:

| Event | Date (approx.) | What’s Special |

|---|---|---|

| March Equinox | March 20 | Sun crosses celestial equator going north; day ≈ night everywhere* |

| June Solstice | June 21 | Sun reaches farthest north; longest day in N. Hemisphere |

| September Equinox | Sept. 22 | Sun crosses celestial equator going south; day ≈ night everywhere* |

| December Solstice | Dec. 21 | Sun reaches farthest south; shortest day in N. Hemisphere |

*“Day ≈ night” is approximate. Atmospheric refraction bends sunlight, making the Sun visible slightly before it geometrically rises and after it geometrically sets. This adds a few minutes of daylight. The Sun’s finite angular size also contributes — sunrise is defined as when the Sun’s edge (not center) crosses the horizon.

Solstice: From Latin sol (sun) + sistere (to stand still). The Sun reaches its most extreme northern or southern position and appears to “pause” before reversing direction.

Equinox: From Latin aequus (equal) + nox (night). Day and night are approximately equal in length worldwide.

Earth’s orbit and axial tilt: the seasons story (Credit: (A. Rosen/ChatGPT))

On the equinoxes, the Sun is located:

- Directly over the North Pole

- On the celestial equator

- At its closest point to Earth

- At its farthest point from Earth

B) On the celestial equator. At the equinoxes, the Sun crosses the celestial equator (the intersection of the ecliptic and celestial equator). This means the Sun appears directly overhead at noon for observers on Earth’s equator, and day length approximately equals night length for all latitudes (with small deviations due to atmospheric refraction and the Sun’s finite size).

Angular Size: How Big Things Look

The Fundamental Insight

Here’s a question that seems simple but isn’t: How big is the Moon?

Your instinct might be to answer in kilometers (the Moon’s diameter is about 3,474 km). But that’s not what you see. What you see is how much of your field of view the Moon occupies — its angular size.

The Moon’s angular size is about 0.5° (half a degree). Hand-based “sky ruler” estimates vary by person, so treat them as rough: the Moon is about half the width of your pinky finger at arm’s length (approximately).

These are approximate (your mileage will vary depending on hand size and arm length):

- Pinky width at arm’s length: ~1–1.5°

- Thumb width at arm’s length: ~2°

- Fist width at arm’s length: ~10°

- Thumb-to-pinky span (outstretched hand): ~20–25°

Use these as order-of-magnitude checks, not precision tools.

Angular size: The angle an object subtends (spans) as seen from the observer. Measured in degrees, arcminutes (1° = 60’), or arcseconds (1’ = 60”).

| Unit | Relation | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 degree (°) | Base unit | Thumb width at arm’s length ≈ 2° |

| 1 arcminute (’) | 1° = 60’ | Human eye resolution ≈ 1’ |

| 1 arcsecond (“) | 1’ = 60” (so 1° = 3600”) | Telescope resolution territory |

Useful conversion: 0.5° = 30’ = 1800”

Worked example: Convert 0.5° into arcminutes and arcseconds.

- \(0.5^\circ \times \frac{60\ \text{arcmin}}{1^\circ} = 30\ \text{arcmin}\)

- \(30\ \text{arcmin} \times \frac{60\ \text{arcsec}}{1\ \text{arcmin}} = 1800\ \text{arcsec}\)

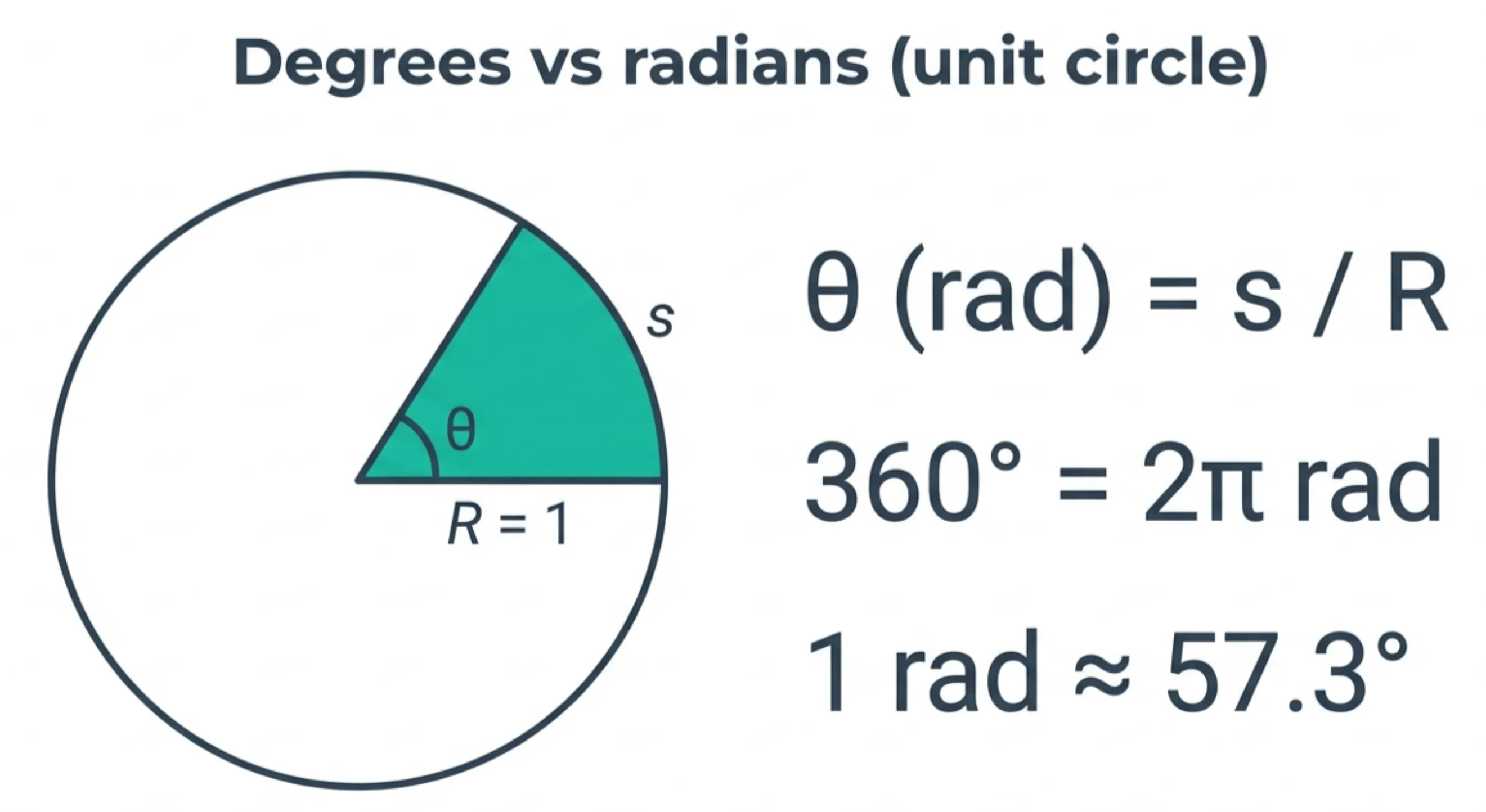

Radians (why they show up in formulas): A radian is defined so that

\[\theta\ (\text{radians}) = \frac{\text{arc length}}{\text{radius}}\]

That’s why radians are sometimes described as “unitless” — it’s a length ratio. In degrees, a full circle is \(360^\circ\); in radians, a full circle is \(2\pi\):

\[360^\circ = 2\pi\ \text{rad} \quad \text{and} \quad 1\ \text{rad} \approx 57.3^\circ\]

Degrees versus radians on the unit circle (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Why we’ll use arcseconds later (spoiler): When we measure tiny angles for very distant stars (parallax), degrees are too coarse. Arcseconds are a convenient unit at that scale.

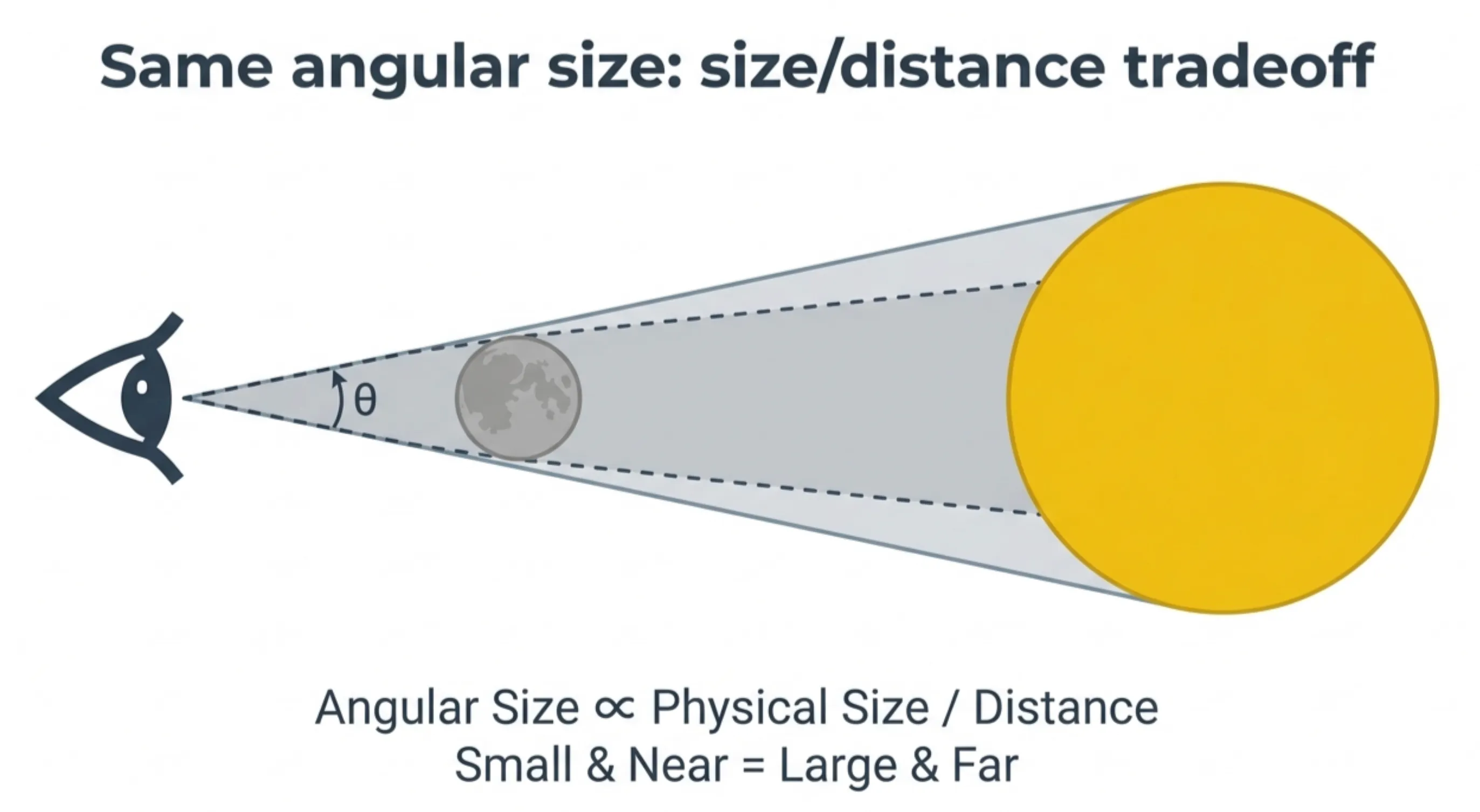

The key insight: Angular size depends on both physical size and distance.

A large object far away can have the same angular size as a small object nearby. This is why the Sun and Moon appear nearly the same size in our sky — despite the Sun being about 400× larger. The Sun is also about 400× farther away, and the two effects almost perfectly cancel.

Angular size: the distance–size ambiguity (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Two planets have the same angular size as seen from Earth. This means:

- They have the same physical diameter

- They are at the same distance

- The ratio of their diameters equals the ratio of their distances

- They have the same luminosity

C) The ratio of their diameters equals the ratio of their distances. If Planet A has twice the diameter of Planet B but is also twice as far away, they’ll have the same angular size. Angular size = physical size / distance (for small angles). Same angular size means the size-to-distance ratio is the same.

🔭 Demo Exploration: Angular Size

Open the Angular Size Demo: astrobytes-edu.github.io/astr101-sp26/demos/angular-size/

This demo lets you explore how angular size depends on both physical size and distance.

What you’ll see in the demo: - Angular Size readout (auto units: ° / ′ / ″) - Physical Size and Distance sliders/values - Presets: Everyday Objects and Astronomical Objects - Time Evolution (for Moon): See how the Moon’s angular size changes as its distance varies - (Note: the angular-size readout may automatically switch units as the angle gets smaller.)

Demo Mission 1: Building Intuition

Do this: 1. In Presets, choose Everyday Objects 2. Select an object (like a basketball) 3. Change the Distance slider and watch the Angular Size change

Questions to answer: - When you double the distance, what happens to angular size? (Halves? Doubles? Stays same?) - When you double the physical size at the same distance, what happens to angular size?

- Doubling distance → halves angular size (inverse relationship)

- Doubling physical size → doubles angular size (direct relationship)

Claim: Angular size is proportional to physical size and inversely proportional to distance.

Evidence: The demo’s Angular Size readout halves when you double distance, and doubles when you double physical size. This confirms the small-angle formula: Angular size \(\propto\) (Physical size / Distance).

Demo Mission 2: Astronomical Objects

Do this: 1. Switch to Astronomical Objects presets 2. Select Sun and note its angular size 3. Select Moon (Today) and note its angular size

The key observation: How do the angular sizes compare?

Both the Sun and Moon have angular sizes of approximately 0.5° (half a degree). This is a remarkable cosmic coincidence! The Sun is about 400× larger than the Moon but also about 400× farther away, so they appear almost exactly the same size.

Claim: The Sun and Moon have nearly identical angular sizes despite vastly different physical sizes.

Evidence: The demo’s Angular Size readout shows ~0.5° for both objects. This coincidence is why we can have total solar eclipses — the Moon can just barely cover the Sun completely.

Demo Mission 3: The Moon’s Changing Angular Size

Do this: 1. Keep Moon selected 2. Use the Time Evolution feature to see how the Moon’s distance (and therefore angular size) changes over its orbit 3. Note the range of angular sizes

Why this matters: The Moon’s orbit is elliptical, so its distance from Earth varies. When the Moon is closer (perigee), it appears larger. When it’s farther (apogee), it appears smaller.

The Moon’s angular size varies from about 0.49° (at apogee, farthest) to about 0.56° (at perigee, closest). The Sun’s angular size also varies slightly (about 0.52° to 0.54°).

Claim: The Moon’s angular size varies enough to determine whether a solar eclipse is total or annular.

Evidence: The demo’s Time Evolution shows the Moon’s angular size ranging from smaller than the Sun’s (~0.49°) to larger than the Sun’s (~0.56°). When the Moon appears larger, total eclipses are possible; when smaller, only annular eclipses occur. We’ll explore this more in Lecture 4!

The Moon appears about the same angular size as the Sun because:

- They are the same physical size

- They are at the same distance from Earth

- The Moon is ~400× smaller but also ~400× closer

- The Moon is ~400× larger but also ~400× farther

C) The Moon is ~400× smaller but also ~400× closer. The Sun’s diameter is about 1.4 million km; the Moon’s is about 3,500 km — a ratio of 400:1. The Sun is about 150 million km away; the Moon is about 380,000 km away — also a ratio of roughly 400:1. These factors cancel, giving nearly equal angular sizes.

For objects whose angular size is small (less than a few degrees), there’s a simple relationship:

Why radians first? The small-angle relationship comes from basic circle geometry (arc length = radius × angle) and trigonometry, and those relationships are simplest and most “natural” when the angle is measured in radians. We often report angles in degrees/arcminutes/arcseconds because they’re easier to interpret, so we convert at the end.

\[\theta = \frac{D}{d}\]

where: - \(\theta\) is the angular size in radians - \(D\) is the object’s physical diameter - \(d\) is the distance to the object

To convert to degrees, multiply by 57.3 (since 1 radian ≈ 57.3°):

\[\theta_{\text{degrees}} = 57.3^\circ \times \frac{D}{d}\]

Example: What’s the angular size of the Moon? - Moon’s diameter: \(D = 3474\) km - Moon’s distance: \(d = 384000\) km

\[\theta = 57.3^\circ \times \frac{3474~\text{km}}{384000~\text{km}} = 57.3^\circ \times 0.00905 = 0.52^\circ\]

That’s about half a degree — roughly ¼ of your thumb width at arm’s length.

Draw an observer (you), an object, and the angle formed by lines from your eye to the object’s edges. This angle is the angular size.

Now draw the same object at twice the distance. What happens to the angle?

The Sun-Moon Coincidence

It’s worth pausing to appreciate how remarkable the Sun-Moon angular size match is.

The Sun is a star — a ball of plasma 1.4 million kilometers across, located 150 million kilometers away.

The Moon is a small rocky body 3,474 kilometers across, located a mere 384,000 kilometers away.

There’s no fundamental requirement that these two appear the same size — it’s a coincidence of our particular moment in cosmic history.

And it wasn’t always this way. The Moon is slowly drifting away from Earth (about 3.8 cm per year — we can measure this with lasers!). Billions of years ago, the Moon appeared much larger. In a few hundred million years (on the order of ~600 million), the Moon will appear too small to ever fully cover the Sun. We live in a privileged cosmic moment: in the distant past, annular solar eclipses weren’t possible because the Moon appeared larger than the Sun; in the far future, total solar eclipses won’t be possible because the Moon will appear smaller than the Sun.

In several hundred million years, total solar eclipses will:

- Be more common because the Moon will be closer

- Be impossible because the Moon will appear smaller than the Sun

- Last longer because the Sun will be dimmer

- Occur at the same rate as today

B) Be impossible because the Moon will appear smaller than the Sun. The Moon is receding from Earth at about 3.8 cm/year. Over hundreds of millions of years, this adds up. Eventually, the Moon’s angular size will always be smaller than the Sun’s, meaning it can never fully cover the Sun. Only annular eclipses (with a visible ring of sunlight) and partial eclipses will be possible.

Connecting the Concepts

Let’s step back and see how today’s concepts fit together:

The celestial sphere is our map for tracking directions in the sky. It’s defined by projecting Earth’s features (equator, poles) outward and tracking the Sun’s apparent motion (the ecliptic).

Seasons result from the 23.5° tilt between Earth’s rotation axis and its orbital plane. This tilt causes the Sun’s path across the sky to change throughout the year, varying both the directness of sunlight and the length of each day. Seasons are ultimately about solar energy per square meter per day.

Angular size reminds us that what we see depends on geometry — both the object’s true size and its distance. The Sun and Moon having nearly equal angular sizes is a coincidence that enables total solar eclipses.

The through-line: All of today’s concepts are about geometry — the geometry of directions (celestial sphere), illumination (seasons), and apparent size (angular size). This geometric thinking will serve you throughout astronomy.

Next time: We’ll apply angular size to understand Moon phases and eclipses. The geometry you’ve learned today is the foundation for explaining why the Moon appears to change shape each month, and why eclipses don’t happen every month.

This same geometry returns later in the semester:

- Exoplanet transits: A planet crosses in front of a star, blocking a tiny fraction of its light. The depth of the dip depends on the area ratio (planet disk vs. star disk).

- Eclipsing binary stars: Two stars orbit each other and periodically eclipse, producing a repeating brightness pattern.

- Stellar/planet sizes from light curves: With good geometry and timing, eclipses/transits let us infer physical sizes and orbits from how the brightness changes.

Here’s a preview of what’s coming in Lecture 4:

Moon phases are NOT caused by Earth’s shadow. They’re a consequence of seeing different portions of the Moon’s lit half as the Moon orbits Earth. The geometry is similar to how a ball appears to “change shape” as you walk around it under a single light source.

Eclipses require a special alignment — the Moon must be near the points where its orbit crosses the ecliptic. This happens only about twice a year, which is why eclipses are relatively rare events.

Why not monthly? The Moon’s orbit is tilted about 5° relative to the ecliptic. Usually, the Moon passes above or below the Sun (at new moon) or above or below Earth’s shadow (at full moon). Only when the Moon is near a “node” — where its orbit crosses the ecliptic — can eclipses occur.

Practice Problems

Core Problems (Everyone Should Do These)

1. Observable vs. Inferred. When you look at the Moon in the sky, which quantity are you directly observing?

- The Moon’s distance

- The Moon’s angular size

- The Moon’s physical diameter

- The Moon’s mass

2. Constellation Depth. Explain in 2-3 sentences why the stars in a constellation don’t represent a physical group of stars.

3. Seasons Logic. Australia experiences summer in December. How does this observation refute the “distance causes seasons” hypothesis?

4. Equinox Geometry. On the equinoxes, the Sun rises approximately due east and sets approximately due west for most locations on Earth. Why is this related to the Sun being on the celestial equator? (Note: Atmospheric refraction and local horizon effects cause small deviations from exactly due east/west.)

5. Arctic Extremes. Explain why the Arctic has 24-hour daylight in June but 24-hour darkness in December, using the concept of Earth’s axial tilt.

6. Why Geometry? This lecture emphasized geometric reasoning. In 3-4 sentences, explain why astronomers need to think about the sky as a geometric system of directions rather than just a collection of pretty lights.

7. Demo Integration. Describe one misconception that the Seasons demo helped you correct, and explain how the demo’s specific features (readouts, overlays, etc.) provided the evidence.

Challenge Problems

8. Angular Size Practice. Mars has a diameter of \(D=6,792\) km. When Mars is at its closest approach to Earth (about \(d=55\) million km), what is its angular size in arcseconds? (Use the small-angle formula: \(\theta = 57.3^{\circ} \times D/d\), then convert to arcseconds using 1° = 3600”.)

9. Angular Size Scaling. A satellite appears to have an angular size of 2 arcminutes when at 400 km altitude. What would its angular size be if it moved to 800 km altitude? Hint: Use the ratio method.

10. Day Length. At a latitude of 45°N, the day length on the summer solstice is about 15.5 hours. How many more hours of sunlight does this provide compared to a 12-hour equinox day? Over a 90-day summer, approximately how many extra hours of sunlight does this location receive compared to the equator (assuming 12-hour days at the equator year-round)?

11. Sun Altitude (Noon Altitude Formula). At local noon, the Sun reaches its maximum altitude for the day. Use:

\[h_{\text{noon}} = 90^\circ - \left|\phi - \delta\right|\]

where \(\phi\) is your latitude and \(\delta\) is the Sun’s declination (both in degrees). Absolute value just means “take the positive angular separation” between \(\phi\) and \(\delta\).

For San Diego, \(\phi = 32^\circ\) N. Complete the table and show your work for each row:

| Date | \(\delta\) (Sun declination) | \(h_{\text{noon}}\) (degrees above S horizon) |

|---|---|---|

| Summer solstice | \(+23.5^\circ\) | |

| Winter solstice | \(-23.5^\circ\) |

Then, in 1–2 sentences: which noon altitude is higher, and what geometric reason explains the difference?

Bridge Problems (Connects to Future Topics)

12. Observable → Model → Inference. An astronomer measures that a star’s position in the sky shifts by 0.5 arcseconds over 6 months. Following the Observable → Model → Inference pattern from Lecture 1:

- What is being measured? (Which of the four observables?)

- What physical model connects this measurement to distance?

- What could you infer about this star?

Glossary

No glossary terms for lecture 3.