From Ancient Skies to Kepler’s Laws

Lecture 5 Reading Companion

For 2,000 years, astronomers tried to explain why planets wander across the sky. Kepler finally cracked the code: planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, following three elegant mathematical rules. These laws describe what planets do with stunning precision — but they don’t explain why. That’s Newton’s job.

This page is both your assigned reading and your reference guide for celestial mechanics. Come back to it while doing practice problems.

Musts for today (~20 min):

- The Big Idea

- Retrograde Motion explanation

- All three of Kepler’s Laws (especially the one-sentence statements)

- Stop at every Check Yourself question — don’t just read past them

Skim now, read carefully later:

- Part 1 (historical overview) — context, not content you’ll be tested on

- Deep Dives and worked examples

Key skill: By the end, you should be able to use Kepler’s Third Law (\(P^2 \propto a^3\)) — especially the ratio method — to connect orbital periods and semi-major axes.

Reassurance: The history sets the scene but isn’t the exam focus. Kepler’s three laws are the core — make sure you can state and apply them.

If you only remember three things from Part 1:

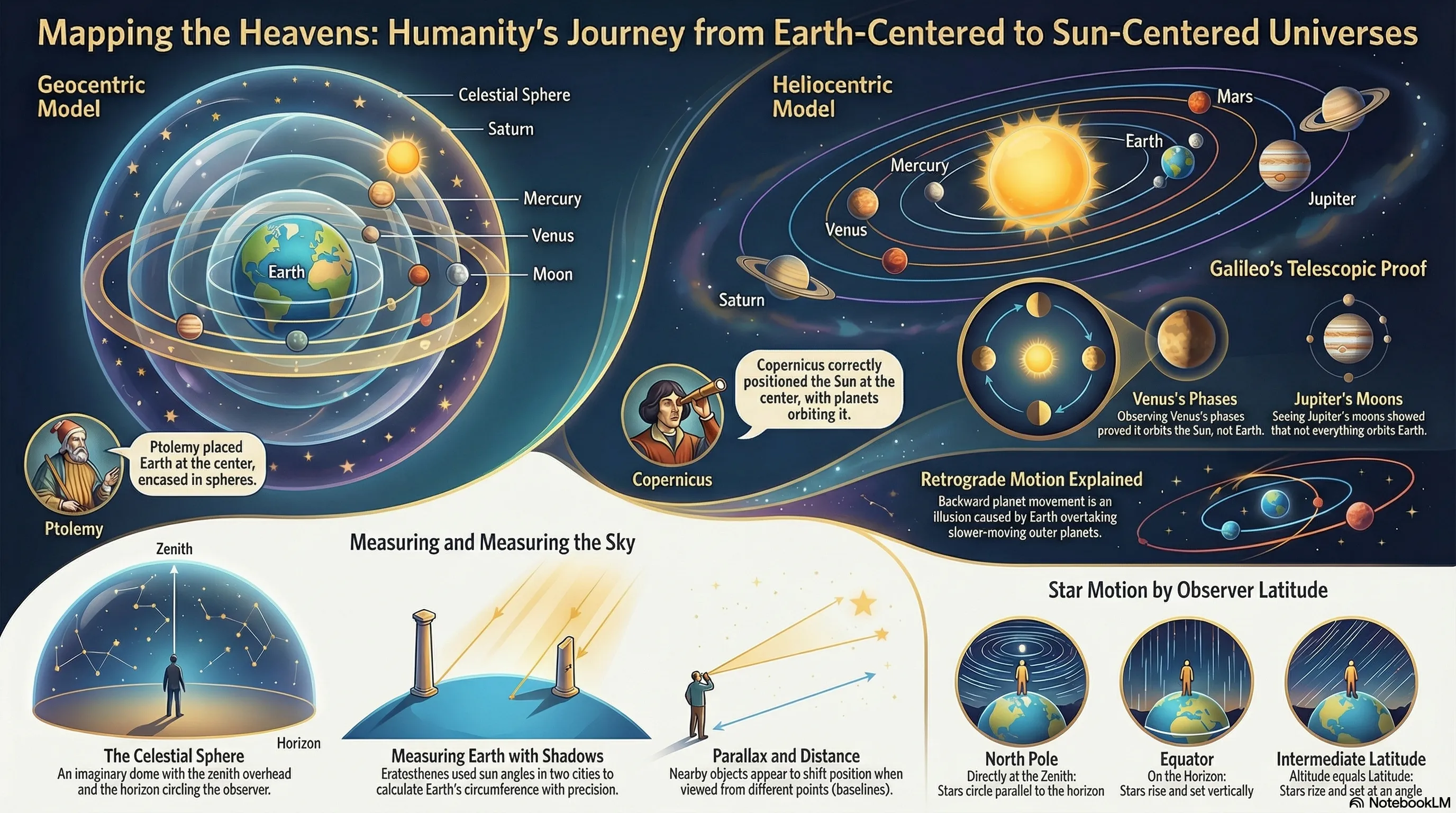

The problem: Planets appear to move backward sometimes (retrograde). The geocentric model “solved” this with dozens of circles-on-circles.

The shift: Copernicus proposed the Sun at center. Suddenly retrograde was just Earth passing outer planets — no epicycles needed.

The breakthrough: Kepler ditched circles for ellipses, and everything finally fit. Simpler model, better predictions.

Now on to the laws themselves…

The Wanderers

Look up at the night sky, and you’ll see a reassuring predictability. Stars rise in the east, arc overhead, and set in the west. The same constellations return each season, unchanged for millennia. But ancient observers noticed something troubling: a handful of bright lights didn’t follow the rules. They wandered among the fixed stars, drifting slowly from night to night. The Greeks called them planetes — wanderers. And they did something even stranger: sometimes they appeared to stop, reverse direction for weeks, then resume their forward journey.

What could possibly cause a celestial body to move backward?

Planets never actually reverse their orbital direction. Retrograde motion is an apparent reversal caused by changing viewing geometry as Earth and other planets move at different speeds around the Sun. It’s an illusion of perspective — like when you pass a slower car on the highway and it seems to drift backward relative to distant mountains.

This puzzle — explaining retrograde motion — drove astronomical thinking for two millennia. The answers people proposed reveal how science works: assumptions get built into models, and sometimes the right answer requires abandoning assumptions everyone took for granted.

Observable: Mars appears to reverse direction against the background stars for several weeks each year. (Position observation)

Model: Earth and Mars both orbit the Sun; Earth orbits faster. When Earth “passes” Mars, Mars appears to drift backward — like passing a car on the highway.

Inference: Retrograde is an apparent motion caused by geometry, not a real reversal. This supports the heliocentric model.

What to notice: apparent retrograde motion comes from Earth overtaking Mars in their heliocentric orbits. (Credit: cococubed.com)

Part 1: The Cosmic Puzzle

The Ancient Answer

Earth at the center felt obvious. We don’t feel Earth moving. Stars appear to rotate around us. The intuition matched everyday experience.

Geocentric model: A model with Earth at the center of the universe.

Around 150 CE, the astronomer Claudius Ptolemy codified this into a complete mathematical system. In his model, Earth sat stationary at the center while the Sun, Moon, and planets orbited around it on circular paths. But there was a problem: circles alone couldn’t explain retrograde motion.

Ptolemy’s solution was ingenious. He proposed that planets move on small circles called epicycles, whose centers travel along larger circles called deferents. When a planet is on the “backward” part of its epicycle, it appears to reverse direction against the background stars. It worked! Predictions matched observations reasonably well.

Epicycle: A small circle on which a planet moves, whose center travels along a larger circle (deferent).

But at what cost? By medieval times, the model required dozens of circles — epicycles on epicycles — to match increasingly precise observations. The system was accurate but ugly, a baroque machinery of nested circles.

What to notice: epicycle + deferent can reproduce retrograde-like backtracking while preserving the assumption of circular motion around Earth. (Credit: Illustration: A. Rosen (SVG))

The geocentric model protected two assumptions:

- Earth is stationary and central — we don’t feel motion, so we must not be moving

- Circular motion is natural and perfect — orbits must be circles because circles are geometrically “perfect”

What happens when we challenge these?

During Mars retrograde, Mars is actually moving:

- Backward in its orbit

- Forward in its orbit

- Stopped in space

- Falling toward the Sun

B) Forward in its orbit. Mars never reverses direction. Retrograde is an apparent motion caused by Earth (which orbits faster) passing Mars. It’s like passing a slower car — the car seems to drift backward against the distant background, even though it’s still moving forward.

The Revolution Begins

Copernicus — A Simpler Idea

In 1543, Nicolaus Copernicus proposed something radical: the Sun sits at the center, and Earth is just another planet orbiting around it.

Heliocentric model: A model with the Sun at the center, planets orbiting it.

This seemingly simple change had a profound consequence for retrograde motion. If both Earth and Mars orbit the Sun, and Earth orbits faster (being closer to the Sun), then when Earth “passes” Mars, Mars appears to drift backward against the distant stars — just like passing a car on the highway. No epicycles needed to explain retrograde.

Copernicus knew his idea was controversial. Placing Earth among the planets — rather than at the center of creation — challenged centuries of philosophical and theological tradition. He delayed publication for decades, and his complete work, De revolutionibus, appeared in 1543 — the year of his death.

But Copernicus’s model wasn’t perfect. He still believed in circular orbits, so he still needed some epicycles to match observations. The model was conceptually simpler but not yet mathematically elegant. The assumption of circular motion remained protected.

When two models fit the data equally well, prefer the one that makes fewer assumptions.

Named after 14th-century philosopher William of Ockham, this principle is a heuristic — a useful guide, not a guarantee of truth. Simpler isn’t always right, but unnecessary complexity is a warning sign.

Copernicus’s model was conceptually simpler: no epicycles needed just to explain retrograde. But he still assumed circular orbits, so some complexity remained. The full simplification would come with Kepler.

What was the key advantage of Copernicus’s heliocentric model over Ptolemy’s geocentric model?

- It was more accurate at predicting planetary positions

- It explained retrograde motion as geometry rather than requiring epicycles

- It was immediately accepted by the Church

- It used ellipses instead of circles

B) It explained retrograde motion as geometry. In the heliocentric model, retrograde is just Earth passing an outer planet — no epicycles needed for this phenomenon. (Accuracy wasn’t dramatically better since Copernicus still used circles. Ellipses came later, with Kepler.)

The Evidence Mounts

Giordano Bruno (1548–1600) embraced and extended Copernican ideas, proposing an infinite universe filled with countless worlds. In 1600, the Roman Inquisition executed him for heresy. His cosmological views were part of the context, but his execution was for broader theological heresies — denying core Church doctrines — not simply for supporting heliocentrism. Still, his fate sent a clear message about the risks of challenging established worldviews.

Galileo Galilei (1564–1642) provided actual evidence. In 1610, using a telescope he’d refined, he discovered four moons orbiting Jupiter. This proved that not everything orbited Earth. He also observed that Venus showed a full range of phases — from crescent to full — which was impossible in the classic Ptolemaic model where Venus always stayed between Earth and Sun.

Venus’s phases showed that Venus must orbit the Sun — ruling out the simplest version of Ptolemy’s model, where Venus always stays between Earth and the Sun. However, the phases didn’t uniquely prove Copernicus: a “hybrid” Tychonic system (Earth-centered but with planets orbiting the Sun) could also explain them. The evidence was mounting, but not yet decisive.

Despite the evidence, Galileo faced the Inquisition in 1633 and was forced to publicly renounce his support for heliocentrism. He spent his remaining years under house arrest. The scientific evidence eventually won — but it took courage to follow it.

When Galileo pointed his telescope at Jupiter in January 1610, he saw something no human had ever seen: four tiny points of light arranged in a line near the planet. Over several nights, he watched them shift position — clearly orbiting Jupiter, not Earth.

These moons (now called Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto — the “Galilean moons”) provided direct evidence that not everything orbited Earth. Here was a miniature planetary system, visible to anyone with a telescope.

Today, Europa is one of the most promising places to search for extraterrestrial life — its icy surface hides a vast liquid ocean that may harbor conditions suitable for biology.

Islamic Astronomy — Preserving and Advancing the Flame

While medieval Europe largely set aside the Greek astronomical tradition, scholars in the Islamic world preserved, translated, and advanced it. Astronomers like Al-Battani (858–929 CE) refined Ptolemy’s measurements and corrected errors. Al-Tusi (1201–1274) developed mathematical tools that would later influence Copernicus. When European scholars eventually rediscovered Greek astronomy, it was often through Arabic translations and Islamic commentaries. The scientific revolution didn’t emerge from nowhere — it built on a millennium of scholarship across cultures.

Tycho Brahe — The Master Observer

Tycho Brahe (1546–1601) was a Danish nobleman and the greatest naked-eye observer in history. He built Uraniborg, a state-of-the-art observatory, and collected more than twenty years of planetary position data with unprecedented precision.

Ironically, Tycho proposed his own hybrid model: Earth-centered, but with planets orbiting the Sun. But his data would prove something else entirely — in the hands of his young assistant.

When Tycho died in 1601, his decades of meticulous observations passed to Johannes Kepler. Kepler would spend the next twenty years wrestling with this data, trying to find the mathematical pattern hidden within. The answer would require abandoning yet another assumption — and it would transform astronomy forever.

Each model so far has protected certain assumptions:

- Ptolemy: Earth at center, circular motion is natural

- Copernicus: Circular motion is natural (even if Sun is at center)

- Tycho: Earth is stationary (even if planets orbit Sun)

What assumption will Kepler finally abandon?

What to notice: each revolution in astronomical thinking required abandoning an assumption — from Earth-centered (Ptolemy) to Sun-centered (Copernicus) to elliptical (Kepler). (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Part 2: Kepler’s Laws — The Main Event

Kepler’s Struggle

Johannes Kepler (1571–1630) inherited Tycho’s data — the best observations ever collected. His task: find the mathematical pattern behind Mars’s orbit. Kepler believed in mathematical harmony — surely the answer would be beautiful.

For years, Kepler tried to fit Mars’s orbit to a circle. He tried offset circles, varying speeds, combinations of circles. Nothing worked. The errors were small — about 8 arcminutes, a quarter of the Moon’s width — but they were consistent. Tycho’s data was too good to ignore.

Finally, Kepler tried something radical: an ellipse. And suddenly, everything fit. The data that had resisted circles for twenty years surrendered immediately to this humble oval. Kepler later wrote that he felt like he had “awoken from a sleep.”

“I was almost driven to madness in considering and calculating this matter. I could not find out why the planet would rather go on an elliptical orbit… With reasoning derived from physical principles, agreeing with experience, there is no figure left for the orbit of the planet but a perfect ellipse.”

— Johannes Kepler, Astronomia Nova (1609)

Kepler’s breakthrough wasn’t a flash of insight — it was twenty years of grueling calculation. He tried circles, offset circles, ovals, and dozens of variations before the ellipse finally fit.

This was Occam’s Razor vindicated. For centuries, astronomers had added complexity — epicycle upon epicycle — to preserve the “perfection” of circles. Kepler let go of that assumption. One ellipse replaced dozens of circles. The math became cleaner, the predictions more accurate.

Kepler’s First Law — The Shape of Orbits

Planets orbit the Sun in ellipses, with the Sun at one focus.

What’s an Ellipse?

An ellipse is an oval shape with a precise mathematical definition. It has two special points inside called foci (singular: focus). The defining property: the sum of distances from any point on the ellipse to both foci is constant.

Ellipse: An oval-shaped curve where the sum of distances from any point to two fixed points (foci) is constant.

Focus (plural: foci): One of two special points inside an ellipse; the Sun sits at one focus of each planetary orbit.

What to notice: eccentricity e controls how stretched an orbit is—and how far the focus (where the Sun sits) is from the center. (Credit: (A. Rosen/Codex))

Here’s how to draw an ellipse with household items:

- Put two thumbtacks in a piece of cardboard (these are the foci)

- Tie a loose loop of string around both tacks

- Put a pencil inside the loop and pull it taut

- Move the pencil around, keeping the string taut

- The shape you trace is an ellipse!

The string ensures that the total distance to both foci stays constant — that’s the defining property of an ellipse.

Key Orbital Terms

| Term | Symbol | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Semi-major axis | \(a\) | Half the longest diameter; the “average” orbital distance |

| Eccentricity | \(e\) | How “squashed” the ellipse is (0 = circle, approaching 1 = very elongated) |

| Perihelion | \(r_p\) | Closest point to the Sun; \(r_p = a(1-e)\) |

| Aphelion | \(r_a\) | Farthest point from the Sun; \(r_a = a(1+e)\) |

What to notice: an orbit is an ellipse with the Sun at one focus; the semimajor axis sets the size. (Credit: cococubed.com)

Notice that the Sun is at one focus, not the center of the ellipse. The other focus is empty — nothing sits there. This offset is why the planet’s distance from the Sun varies throughout its orbit.

Real Planetary Eccentricities

| Planet | Eccentricity | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Venus | 0.007 | Nearly circular |

| Earth | 0.017 | Nearly circular |

| Mars | 0.093 | Noticeably elliptical |

| Mercury | 0.206 | Most eccentric planet |

| Pluto (dwarf) | 0.25 | Highly elliptical |

| Halley’s Comet | 0.97 | Extremely elongated |

Most planets have nearly circular orbits (low eccentricity). This is why Ptolemy and Copernicus got reasonably good results with circles — they were approximately correct. But “approximately” wasn’t good enough for Tycho’s precise data, which revealed the subtle elliptical truth.

Quick calculation: Earth’s eccentricity is 0.017 and its semi-major axis is 1 AU. What are its perihelion and aphelion distances?

\[r_p = a(1-e) = 1 \times (1-0.017) = 0.983 \text{ AU}\] \[r_a = a(1+e) = 1 \times (1+0.017) = 1.017 \text{ AU}\]

Earth’s distance from the Sun varies by about 3.4% over the year — a small effect, but real.

An orbit with eccentricity \(e = 0\) would be:

- A very elongated ellipse

- A perfect circle

- A parabola

- Impossible for a planet

B) A perfect circle. When eccentricity equals zero, the two foci merge into a single point at the center, and the ellipse becomes a circle. A circle is just a special case of an ellipse.

In a planetary orbit, the Sun is located:

- At the center of the ellipse

- At one focus of the ellipse

- At both foci of the ellipse

- Outside the ellipse

B) At one focus of the ellipse. This is Kepler’s First Law. The other focus is empty. Because the Sun is offset from center, the planet’s distance from the Sun changes as it orbits.

🔭 Try It: First Law in the Demo

See the First Law in action! Open the interactive simulation and explore how the Sun’s position relates to the ellipse.

Open the Kepler’s Laws Demo: ../../../demos/keplers-laws/

Demo Mission: The Sun Is Not at the Center

Predict before you explore: If you make an orbit highly elliptical (high eccentricity), where will the Sun be relative to the orbit’s center?

Write your prediction here before continuing: _______________

Do this:

- Set Eccentricity to about 0.6 (fairly elliptical)

- Check the Foci and Apsides boxes (in the overlays row below the presets)

- Observe where the Sun sits relative to the ellipse’s geometric center

Key question: Is the Sun at the center of the ellipse?

The Sun sits at one focus, not at the center. The higher the eccentricity, the more offset the Sun is from center. The other focus is empty — nothing sits there.

Claim: Kepler’s First Law says orbits are ellipses with the Sun at one focus, not at the center.

Evidence: With eccentricity ~0.6, the Sun is clearly offset from the ellipse’s geometric center. The distance from perihelion (closest point) to the Sun is much shorter than from aphelion (farthest point) to the Sun.

Kepler’s Second Law — Orbital Speed

A line connecting a planet to the Sun sweeps out equal areas in equal times.

What This Means

Imagine a line from the Sun to a planet. As the planet moves, this line sweeps out a wedge-shaped area. Kepler discovered: the area swept in any given time interval is always the same, regardless of where the planet is in its orbit.

The consequence: near perihelion (close to Sun), the planet moves faster — it must cover more arc length to sweep the same area with a shorter radius. Near aphelion (far from Sun), the planet moves slower — it covers less arc length to sweep the same area with a longer radius.

What to notice: equal areas are swept in equal times even though the shape of the swept region changes. (Credit: cococubed.com)

What Does “Area” Even Mean Here?

Students sometimes nod at “equal areas” without really understanding what area represents. Here’s the intuition:

The wedge area depends on two things: how far the planet is from the Sun (radius) and how much angle it sweeps (arc). These combine multiplicatively — a bigger radius makes a bigger wedge, and a bigger angle makes a bigger wedge.

So if the radius is smaller (planet near perihelion), the angle must be larger to keep the area the same. Larger angle in the same time = faster motion.

No calculus needed — just geometry. Imagine cutting each wedge out of paper: near perihelion, your paper wedge is short and fat; near aphelion, it’s long and thin. Both pieces weigh the same (same area).

Physical Intuition: The Ice Skater Analogy

Think of an ice skater spinning with arms extended. When they pull their arms in, they spin faster. When they extend arms out, they spin slower.

This is conservation of angular momentum. The same principle applies to planets: closer to Sun means faster; farther from Sun means slower. Kepler described the pattern; Newton would later explain why (angular momentum conservation under central forces).

Angular momentum: A measure of rotational motion. For orbits, it stays constant when only gravity acts — which is why planets speed up when closer to the Sun.

Real-World Example: Earth’s Orbit

| Position | Date | Distance from Sun | Earth’s Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perihelion | ~Jan 3 | 147.1 million km | 30.3 km/s |

| Aphelion | ~Jul 4 | 152.1 million km | 29.3 km/s |

Earth moves about 3% faster in January than in July! This also means Northern Hemisphere winter is slightly shorter than summer — we move through that part of our orbit faster.

A planet is moving fastest when it is at:

- Aphelion (farthest from the Sun)

- Perihelion (closest to the Sun)

- Halfway between perihelion and aphelion

- The planet moves at constant speed

B) Perihelion. By Kepler’s Second Law, planets sweep equal areas in equal times. When closer to the Sun (smaller radius), the planet must move faster (larger angle) to sweep the same area.

According to Kepler’s Second Law, if a planet takes 30 days to sweep a certain area near aphelion, how long will it take to sweep an equal area near perihelion?

- It depends on exactly where in the orbit

- Less than 30 days (it’s moving faster there)

- Exactly 30 days (equal areas require equal times)

- More than 30 days (it has less distance to cover)

C) Exactly 30 days. Equal areas in equal times means the time depends only on the area, not on position. The planet adjusts its speed to compensate for changing distance.

🔭 Try It: Second Law in the Demo

Now explore the Second Law in the simulation. Watch how orbital speed changes with distance from the Sun.

Open the Kepler’s Laws Demo: ../../../demos/keplers-laws/

Demo Mission: Faster When Closer

Predict before you explore: As you drag the planet from aphelion to perihelion, what will happen to its speed?

Write your prediction here before continuing: _______________

Do this:

- Keep eccentricity at ~0.5 so speed differences are visible

- Check the Equal Areas box (in the overlays row below the presets)

- Click ▶ Play and watch the animation

- Observe the wedge-shaped areas being swept out

Key observations:

- How does the planet’s speed change as it moves around the orbit?

- Are the area wedges all the same size?

The planet moves faster near perihelion and slower near aphelion. The equal-area wedges show this clearly: near perihelion the wedges are short and wide (fast motion, short radius), while near aphelion they’re long and narrow (slow motion, long radius).

Claim: Kepler’s Second Law — equal areas in equal times — means planets speed up when closer to the Sun.

Evidence: The animation shows visibly faster motion at perihelion. The “Show Equal Areas” overlay confirms that despite the speed change, each time interval sweeps the same area.

What to notice: the planets share nearly coplanar orbits, and the outer planets occupy much larger scales. (Credit: cococubed.com)

Kepler’s Third Law — The Period-Distance Relation

The square of a planet’s orbital period is proportional to the cube of its semi-major axis.

\[P^2 \propto a^3\]

In plain English: planets farther from the Sun take disproportionately longer to orbit — not just because they have farther to travel, but because they also move slower.

What This Means

- Period (\(P\)): Time to complete one orbit

- Semi-major axis (\(a\)): Average distance from Sun

Planets farther from the Sun take longer to orbit — but not linearly. The relationship is precise: \(P^2 \propto a^3\).

Why do outer planets take longer to orbit? Two effects compound:

- They have farther to travel (larger orbit circumference)

- They move slower (farther from the Sun means weaker gravitational pull)

These effects combine to give the \(P^2 \propto a^3\) relationship.

How to Use Kepler’s Third Law

You may see the shorthand \(P^2 = a^3\) in some sources. We won’t use that form in this course because it hides the units and quietly bakes in the Sun’s mass. Instead, use one of these unit-safe forms:

Form 1: Proportionality (most general)

\[P^2 \propto a^3\]

This tells you the relationship but not the numbers.

Form 2: Ratio method (recommended default)

If two objects orbit the same central body:

\[\left(\frac{P_2}{P_1}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a_2}{a_1}\right)^3\]

This is the safest approach — the constants cancel, and you don’t need to worry about units as long as you’re consistent.

Form 3: Sun-only scaling (Solar System convenience)

For objects orbiting the Sun, with \(P\) in years and \(a\) in AU:

\[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\]

This works because we’re implicitly comparing to Earth (\(P = 1\) yr, \(a = 1\) AU). But remember: this form only works for the Sun, in these specific units.

Worked Examples

Example 1: A planet orbits the Sun at \(a = 4\) AU. What’s its period?

Using the Sun-only scaling: \[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{4\,\text{AU}}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3 = 64\] \[P = \sqrt{64} \times 1\,\text{yr} = 8 \text{ years}\]

Example 2: A comet has orbital period \(P = 27\) years. What’s its semi-major axis?

\[\left(\frac{27\,\text{yr}}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\] \[729 = \left(\frac{a}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3\] \[a = \sqrt[3]{729} \times 1\,\text{AU} = 9 \text{ AU}\]

(The symbol \(\sqrt[3]{\phantom{x}}\) means “cube root” — the number that, when multiplied by itself three times, gives 729. Since \(9 \times 9 \times 9 = 729\), the cube root of 729 is 9.)

Solar System Examples

| Planet | \(a\) (AU) | \(a^3\) | \(P^2\) | \(P\) (years) | Actual \(P\) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 |

| Mars | 1.52 | 3.51 | 3.51 | 1.87 | 1.88 |

| Jupiter | 5.20 | 141 | 141 | 11.9 | 11.86 |

| Saturn | 9.54 | 868 | 868 | 29.5 | 29.46 |

| Neptune | 30.1 | 27,300 | 27,300 | 165 | 165 |

Notice that \(a^3 \approx P^2\) in every row — that’s the Third Law in action. The agreement is remarkable; Kepler’s pattern fits perfectly.

What to notice: on linear axes, Kepler’s Third Law looks curved — and the inner planets bunch up near the origin. (Credit: Illustration: A. Rosen (SVG))

What to notice: on a log–log plot, Kepler’s Third Law becomes a straight line — the slope (3/2) encodes the exponent. (Credit: Illustration: A. Rosen (SVG))

The same data can look totally different depending on how you scale the axes. On linear axes, the inner planets bunch up; on a log–log plot, the power law becomes a straight line whose slope tells you the exponent.

An asteroid orbits the Sun at a distance of 4 AU. What is its orbital period?

- 4 years

- 8 years

- 16 years

- 64 years

B) 8 years. Using the Sun-only scaling: \[\left(\frac{P}{1\,\text{yr}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{4\,\text{AU}}{1\,\text{AU}}\right)^3 = 64\] So \(P = \sqrt{64}\,\text{yr} = 8\) years.

If a planet’s orbital distance \(a\) increases by a factor of 4, its orbital period \(P\) increases by a factor of:

- 4

- 8

- 16

- 64

B) 8. From \(P^2 \propto a^3\), we get \(P \propto a^{3/2}\). If \(a\) increases by factor 4, then \(P\) increases by factor \(4^{3/2} = (4^3)^{1/2} = 64^{1/2} = 8\).

Alternatively, using the ratio form: \[\left(\frac{P_\text{new}}{P_\text{old}}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a_\text{new}}{a_\text{old}}\right)^3 = 4^3 = 64\] so \(P_\text{new} = 8 \times P_\text{old}\).

Does It Work Elsewhere?

Here’s a question Kepler couldn’t answer: Does the same \(P^2 \propto a^3\) pattern work for Jupiter’s moons? For exoplanets orbiting other stars?

The answer is: yes — same pattern, different constant.

The relationship \(P^2 \propto a^3\) holds for any gravitational two-body orbit. But the constant of proportionality depends on the mass of the central object. Around a more massive star, planets orbit faster at the same distance. Newton would explain why — and turn this into a tool for measuring mass.

Newton showed that Kepler’s Third Law actually comes from gravity:

\[P^2 = \frac{4\pi^2}{G(M + m)} a^3 \approx \frac{4\pi^2}{GM} a^3\]

where \(M\) is the central mass and \(m\) is the orbiting mass (usually negligible).

What’s new compared to Kepler:

- The constant includes \(G\) and the mass of the central object

- The relationship applies to any gravitational system, not just our Solar System

- We can solve for mass! Measure period and distance, then calculate central mass

This is why the “Kepler constant” isn’t really constant — it depends on what you’re orbiting. The Sun-only shorthand hides this by baking in \(M = M_\odot\).

In Lecture 6, we’ll see how this transforms Kepler’s pattern into a mass-measuring tool.

🔭 Demo Exploration: Kepler’s Third Law

You’ve already explored the First and Second Laws in the demo above. Now let’s test the Third Law and preview Newton.

Open the Kepler’s Laws Demo: ../../../demos/keplers-laws/

Demo Mission: Testing \(P^2 \propto a^3\)

Predict before you explore: Earth (at 1 AU) takes 1 year to orbit. If you select a preset with a = 4 AU, what period should you see?

Calculate first: Using \((P/1\,\text{yr})^2 = (a/1\,\text{AU})^3\), if \(a = 4\) AU, then $P = $ _____ years.

Do this:

- Click the Jupiter preset button (~5.2 AU) — the Period readout updates automatically

- Note the Period (P) value shown in the readout panel

- Check: Does \(P^2\) approximately equal \(a^3\)?

- Click Saturn (~9.5 AU) and repeat the check

| Preset | Semi-major Axis (AU) | \(a^3\) | Period (years) | \(P^2\) | Match? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Earth | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | 1.0 | ✓ |

| Jupiter | ~5.2 | ||||

| Saturn | ~9.5 |

Jupiter: \(a \approx 5.2\) AU, so \(a^3 \approx 141\). The demo should show \(P \approx 11.9\) years, and \(P^2 \approx 141\). Match!

Saturn: \(a \approx 9.5\) AU, so \(a^3 \approx 857\). The demo should show \(P \approx 29.5\) years, and \(P^2 \approx 870\). Match!

Claim: Kepler’s Third Law (\(P^2 \propto a^3\)) works precisely across the entire Solar System.

Evidence: The demo’s period readouts for multiple planets match the prediction from the Third Law. This pattern holds from Mercury to Neptune and beyond.

Demo Mission: What Changes With Star Mass? (Preview of Newton)

Predict before you explore: If you switch to Newton Mode and double the star’s mass, what will happen to the orbital period at the same distance?

Write your prediction here before continuing: _______________

Do this:

- Click NEWTON MODE at the top of the demo

- Note the current period at \(a = 1\) AU with Star Mass (M★) = 1.0 M☉

- Drag the Star Mass (M★) slider to 2.0 M☉

- Observe what happens to the period

Doubling the star mass makes the planet orbit faster (shorter period) at the same distance. With \(M = 2\,M_\odot\), the period at 1 AU is about 0.71 years instead of 1 year.

Claim: The “constant” in Kepler’s Third Law depends on the central mass. More massive star means faster orbits at the same distance.

Evidence: The demo shows that \(P^2 = a^3\) only works for a 1 solar mass star. Change the mass, and the relationship changes. This is the preview of Newton: the full law is \(P^2 \propto a^3/M\).

This is why we’ll be able to “weigh” stars and planets in Lecture 6!

Part 3: The Limits of Patterns

What Kepler Could Do

Kepler’s laws provided unprecedented predictive power. Given a planet’s orbital parameters, you could calculate its position at any time. Astronomers could predict eclipses, conjunctions, and planetary positions for centuries. This was a triumph of pattern recognition.

For the first time in history, humanity had a precise mathematical description of planetary motion. No more epicycles. Three elegant laws. Kepler had done what no one before him could: extract the pattern from the noise.

What Kepler Couldn’t Explain

But patterns aren’t explanations. Kepler could tell you that planets follow ellipses and that \(P^2 \propto a^3\), but he couldn’t tell you why.

The unanswered questions:

Why ellipses? Why not circles, or spirals, or some other curve? Kepler couldn’t explain why nature chose this particular shape.

Why do planets speed up near the Sun? Kepler described the pattern (equal areas) but not the physical mechanism causing the speed change.

Why \(P^2 \propto a^3\)? Why this precise mathematical relationship? Why not \(P \propto a\), or \(P^2 \propto a^2\)?

Does this work everywhere? Are Kepler’s laws universal, or specific to our Solar System? Would they apply to planets around other stars?

Empirical law: A pattern or relationship discovered through observation. Describes what happens but doesn’t explain why.

Kepler’s laws are empirical — patterns extracted from data. They describe what happens, beautifully and precisely. But they don’t explain why it happens. Empirical laws are powerful within their domain, but they can’t confidently predict what happens in new situations.

Kepler’s laws are considered “empirical” rather than “physical” because:

- They are approximately true, not exactly true

- They describe patterns without explaining the underlying mechanism

- They only apply to the Solar System

- They were discovered before telescopes existed

B) They describe patterns without explaining the underlying mechanism. Kepler could tell you that planets follow ellipses and that \(P^2 \propto a^3\), but he couldn’t tell you why. The deeper explanation — a physical law — would come from Newton.

The Setup for Newton

For sixty years after Kepler published his laws, the “why” questions remained unanswered. Then, in 1687, Isaac Newton published the Principia Mathematica, and everything changed.

Newton showed that all three of Kepler’s laws are consequences of a single, deeper principle: the law of universal gravitation. Ellipses, equal areas, the period-distance relation — all of them emerge naturally from one equation:

\[F = \frac{Gm_1m_2}{r^2}\]

Kepler gave us a rulebook. Newton will give us the reason the rulebook exists.

In the next lecture, we’ll see how Newton transformed patterns into physics — and in doing so, created a tool that lets astronomers “weigh” objects billions of kilometers away.

Part 4: How Science Evolves

The Power of Simplicity

| Era | Model | Complexity |

|---|---|---|

| Ptolemy (~150 CE) | Geocentric with epicycles | Dozens of circles |

| Copernicus (1543) | Heliocentric with epicycles | Fewer circles, still complex |

| Kepler (1609–1619) | Heliocentric with ellipses | 3 laws, no epicycles |

Each step toward truth was also a step toward simplicity. The pattern isn’t guaranteed — nature doesn’t owe us elegance — but it’s striking how often correct theories turn out to be simpler than their predecessors.

When you find yourself adding complexity upon complexity to save a theory, it might be time to question the theory’s core assumptions.

Building on Predecessors

The chain of discovery:

- Islamic scholars preserved and refined Greek astronomy

- Copernicus proposed the heliocentric framework

- Tycho gathered unprecedented precision data

- Kepler found the patterns in that data

- Newton (next lecture) explained why those patterns exist

No one worked in isolation. Each scientist built on what came before. This is how science progresses — not through lone geniuses having sudden revelations, but through communities of scholars, across cultures and centuries, gradually approaching truth.

And the process continues. Newton’s laws would eventually be refined by Einstein. Our best current theories will someday be refined by discoveries we can’t yet imagine.

Which best describes how Kepler made his discoveries?

- He had a sudden flash of insight while observing the planets

- He analyzed decades of precise data collected by Tycho Brahe

- He derived the laws purely from philosophical reasoning

- He used a telescope to make new observations

B) He analyzed decades of precise data collected by Tycho Brahe. Kepler didn’t collect the data himself — he inherited Tycho’s observations. His contribution was mathematical analysis: finding patterns in the numbers. This illustrates how science often involves collaboration across time, with observers and theorists playing complementary roles.

Retrograde motion is an apparent backward motion caused by Earth passing outer planets. Planets never actually reverse.

Kepler’s First Law: Orbits are ellipses with the Sun at one focus.

Kepler’s Second Law: Planets sweep equal areas in equal times, so faster when closer to the Sun.

Kepler’s Third Law: \(P^2 \propto a^3\). Use the ratio form or Sun-only scaling (years/AU) — not the bare “\(P^2 = a^3\)” shorthand. Equivalently, \(P \propto a^{3/2}\).

Empirical vs. Physical: Kepler’s laws describe patterns but don’t explain why. That explanation comes from Newton (Lecture 6).

Occam’s Razor: When models fit equally well, prefer simplicity. Kepler’s 3 laws replaced dozens of epicycles.

Practice Problems

Conceptual Questions

Kepler I (shape): What does it mean to say planets move in elliptical orbits with the Sun at one focus? In your own words, what is the difference between “focus” and “center”?

Kepler II (speed): At what point in an elliptical orbit is a planet moving fastest: perihelion or aphelion? Explain using Kepler’s Second Law.

Kepler II (common misconception): True or False (and explain): “Equal areas swept out in equal times means the planet travels equal distances in equal times.”

Retrograde motion (model-based explanation): Mars appears to move eastward against the stars, then westward for a few weeks, then eastward again. What changes in our viewing geometry makes this happen without Mars actually reversing direction?

Calculations

Kepler I (perihelion/aphelion): Mars has semi-major axis (\(a = 1.52\) AU) and eccentricity (\(e = 0.093\)). Calculate its perihelion distance and aphelion distance.

Kepler III (period): Jupiter’s semi-major axis is (\(a = 5.2\) AU). Use Kepler’s Third Law (in Sun–planet units) to estimate Jupiter’s orbital period (\(P\)) in years.

Kepler III (scaling): A planet has a semi-major axis 4 times larger than Earth’s. By what factor is its orbital period larger than Earth’s? (You can answer with a factor; no need for a full number.)

Ratio method (same central body): Io orbits Jupiter at (\(a_1 = 422{,}000\) km) with period (\(P_1 = 1.77\) days). Callisto orbits at (\(a_2 = 1{,}883{,}000\) km). Estimate Callisto’s period (\(P_2\)) using:

\[\left(\frac{P_2}{P_1}\right)^2 = \left(\frac{a_2}{a_1}\right)^3\]

Synthesis

Observable \(\to\) Model \(\to\) Inference (Kepler III as a tool): You observe a repeating transit-like dip in a star’s brightness every 8 days.

- Observable: What quantity did you measure directly?

- Model: What assumption(s) let you apply Kepler’s Third Law?

- Inference: Estimate the orbital distance (\(a\)) (in AU) assuming a Sun-like star.

Empirical laws and the process of science (Kepler \(\to\) Newton): Kepler found patterns that matched observations, but he could not explain why planets obeyed those patterns. In 3–5 sentences:

- What does it mean for a law to be empirical?

- Why are empirical laws still powerful and “real science” even without a mechanism?

- What did Newton add that changed the story from “what happens” to “why it happens”?

Glossary

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Retrograde motion | The apparent backward motion of a planet against background stars (not an actual reversal) |

| Geocentric model | A model with Earth at the center of the universe |

| Heliocentric model | A model with the Sun at the center, planets orbiting it |

| Epicycle | A circle-on-circle mechanism used in geocentric models to explain retrograde |

| Occam’s Razor | The heuristic that simpler explanations should be preferred, all else equal |

| Ellipse | An oval curve with two foci; planetary orbits are ellipses |

| Semi-major axis (\(a\)) | Half the longest diameter of an ellipse; average orbital distance |

| Eccentricity (\(e\)) | How stretched an ellipse is (0 = perfect circle, close to 1 = very elongated) |

| Perihelion | The point in an orbit closest to the Sun |

| Aphelion | The point in an orbit farthest from the Sun |

| Angular momentum | A measure of rotational motion; conserved under gravity |

| Empirical law | A pattern from data; describes what without explaining why |

No glossary terms for lecture 5.