Moon Geometry

Lecture 4 Reading Companion

Moon phases and eclipses are geometry problems, not mysteries. Once you see them as different viewing angles of illuminated spheres, you can predict what the Moon will look like — and when rare alignments will produce eclipses.

This page is both (1) the assigned reading and (2) your reference manual for lunar geometry. You should expect to come back to it multiple times — before lecture, after lecture, and while doing practice problems.

Default expectation (best): Read the whole page before class (including Check Yourself). Then return to it later when you work the Practice Problems.

If you’re short on time before class (~15 min): Do the Musts for today so you can participate now — then come back and finish the rest.

- Musts for today: The Big Idea • Phases Are NOT Shadows • The Geometry of Illumination • Why Not Monthly?

- Non-negotiable: Stop and answer every Check Yourself question you encounter in these sections (don’t just read past them).

Skim now, read carefully later: Eclipse types, the Deep Dives. Skimming is a preview — you’ll get much more from it after lecture.

Demo Explorations (do these!): This reading integrates two interactive demos. The Moon Phases demo is especially powerful — spend time with it to build intuition.

Reassurance: If phases feel confusing at first, that’s normal. The key is connecting position (where the Moon is in its orbit) to appearance (what it looks like from Earth). The demos make this connection visible. Look for the ✏️ Sketch It prompts throughout — if you can draw it, you understand it.

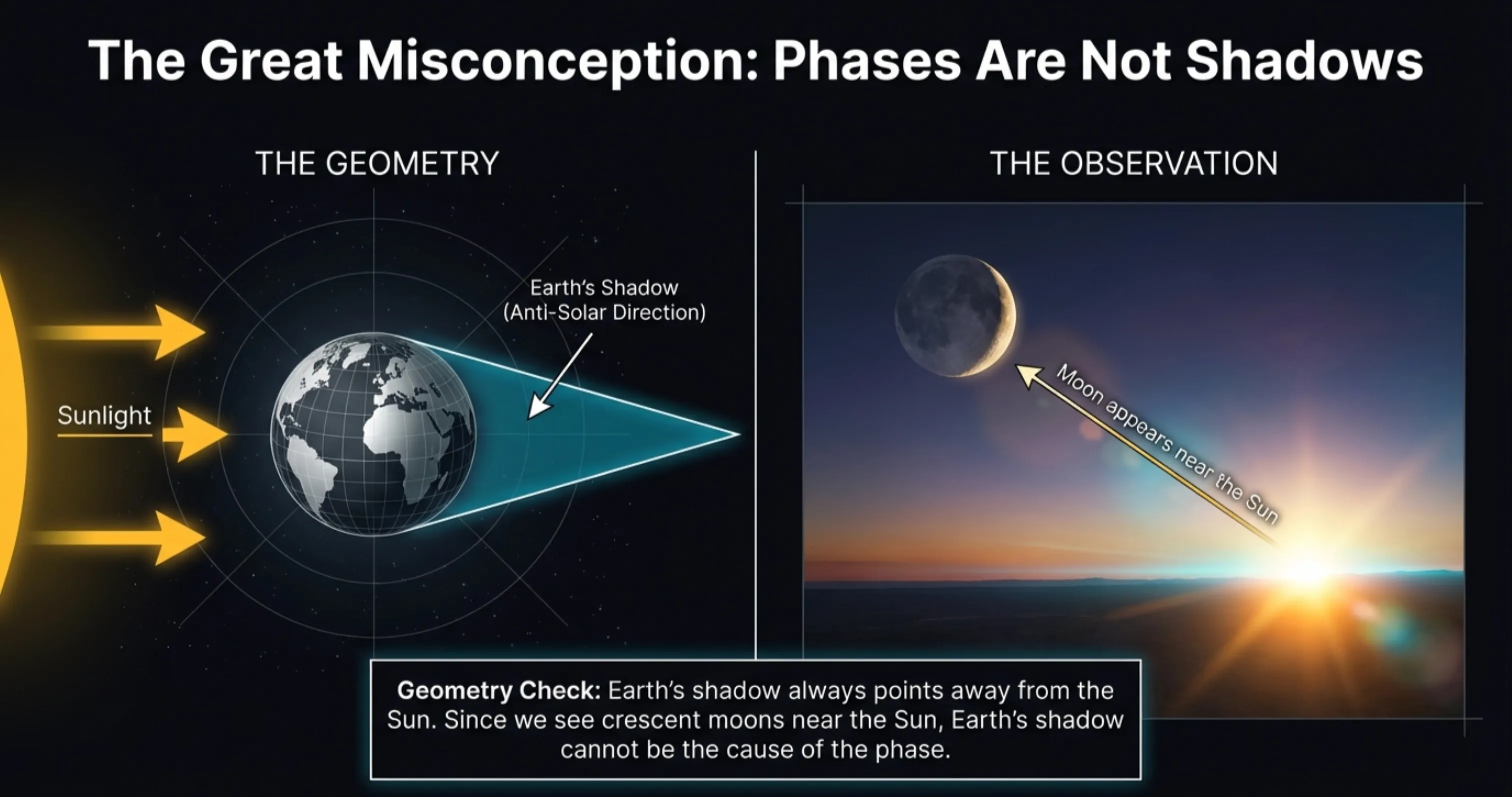

The Misconception: It’s Not Earth’s Shadow

Quick quiz: What causes the Moon’s phases?

If you answered “Earth’s shadow,” you’re not alone — this is one of the most common misconceptions about the Moon. Surveys consistently show that many adults, including college students, believe phases are caused by Earth casting its shadow on the Moon.

It’s a common and very reasonable first guess — but it doesn’t match what we observe.

Here’s the geometry check: Earth’s shadow always points directly away from the Sun. But crescent Moons appear near the Sun in the sky — meaning the Moon is nowhere near the anti-solar direction where Earth’s shadow lives. So Earth’s shadow can’t be causing crescent (or quarter, or gibbous) phases. Earth’s shadow only matters during a lunar eclipse, when the Moon is near the anti-solar direction and near the orbital plane.

What to notice: Moon phases are not caused by Earth’s shadow; phases are about which half of the Moon is lit and what part you can see. (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Earth’s shadow only touches the Moon during a lunar eclipse — which happens a few times per year globally (often around ~2), not every month. If phases were caused by Earth’s shadow, we’d have an eclipse every single night that wasn’t a full moon. That’s obviously not what we observe.

So what does cause phases? Geometry. Pure, beautiful geometry. At all times, the Sun illuminates half of the Moon. Moon phases happen because we see different fractions of that lit half as the Moon orbits Earth.

Moon phases are caused by:

- Earth’s shadow falling on the Moon

- The Moon passing through different parts of Earth’s atmosphere

- The geometry of viewing the Moon’s lit half from different angles

- Clouds on the Moon blocking sunlight

C) The geometry of viewing the Moon’s lit half from different angles. The Sun always illuminates half of the Moon (the half facing the Sun). As the Moon orbits Earth, we see different portions of this lit half — that’s what creates the phases. Earth’s shadow is irrelevant except during the rare occasions of a lunar eclipse.

Moon Phases: The Geometry of Illumination

The Setup: Sun, Earth, Moon

Let’s establish the basic geometry:

- The Sun is far away (about 150 million km) and provides essentially parallel rays of light

- Earth is orbited by the Moon

- The Moon takes about 29.5 days to complete one cycle of phases (new moon to new moon). This is called the synodic month.

The Moon doesn’t produce its own light. It shines by reflecting sunlight. At any moment, exactly half of the Moon — the half facing the Sun — is illuminated.

The Earth-Moon system: orbital geometry that creates phases and eclipses (Credit: Cococubed)

Synodic month: The time from new moon to new moon (one full cycle of phases), about 29.5 days.

There are two useful “months”:

- Sidereal month: the Moon’s orbital period relative to the distant stars, about 27.3 days

- Synodic month: the phase cycle (new moon → new moon), about 29.5 days

Here’s the geometric reason the synodic month is longer:

Earth moves around the Sun by about 1° per day, so during ~27.3 days Earth moves about 27° along its orbit. That changes the Sun-direction. To get back to new moon (Moon lined up with the Sun again), the Moon has to go a little farther than 360° around Earth.

The Moon moves about (360/27.3)/day, so catching up ~27° takes about (27/(13.2/)) days.

So (27.3 + 2.1 ), which is why the synodic month is about 29.5 days.

Compact form (same idea): if (P_{}) is the synodic month, (P_{}) is the sidereal month, and (P_{}) is 1 year, then [ =-. ] You do not need to memorize this equation — use it only if you like it as a clean “motion accounting” statement.

What to notice: At any moment, half of the Moon is illuminated by the Sun; the phase is the fraction of that lit half you can see from Earth. (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

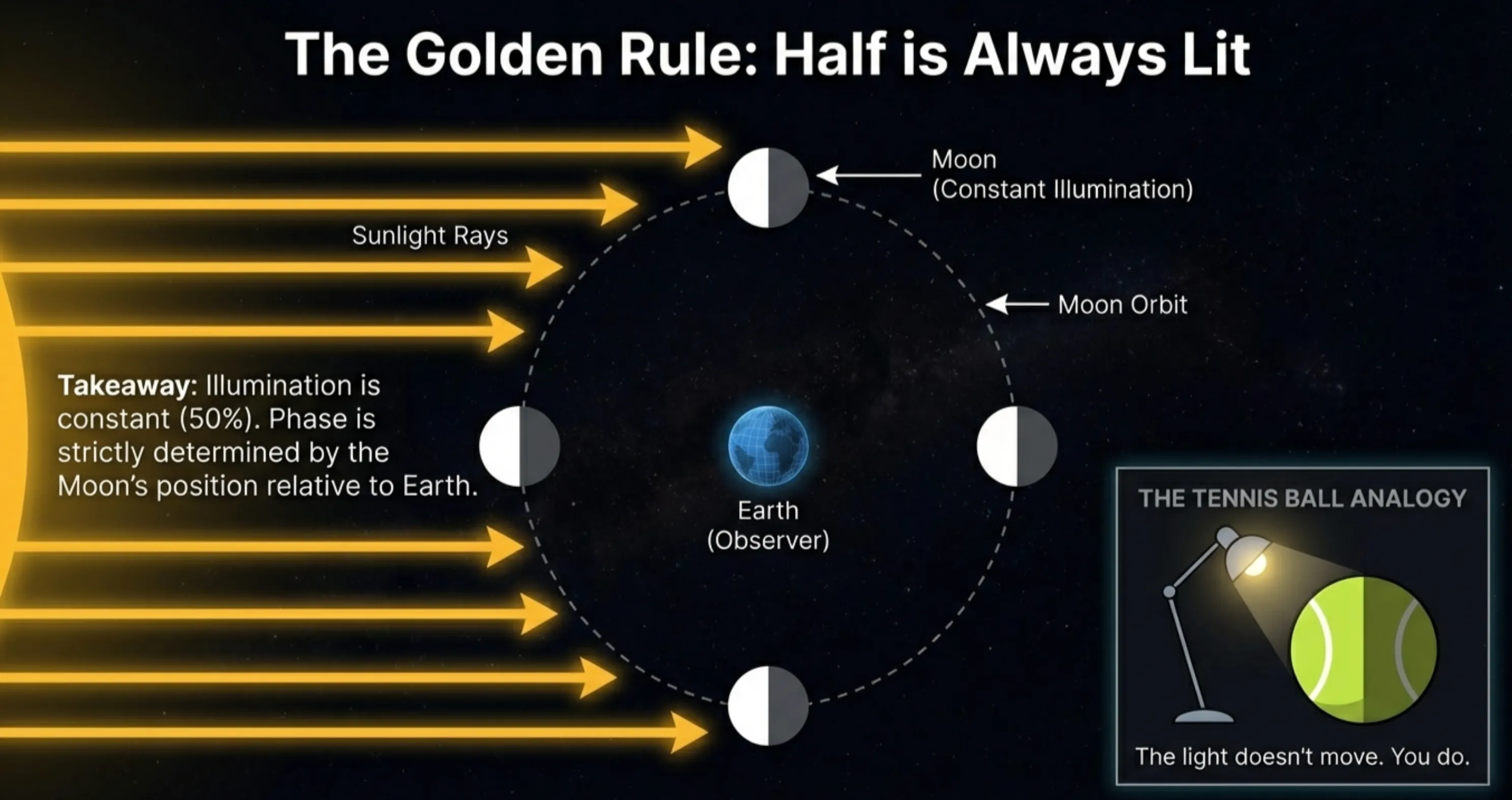

The Key Insight: Half Is Always Lit

The Sun always illuminates exactly half of the Moon.

This is the crucial insight. The amount of the Moon that’s lit doesn’t change. What changes is how much of that lit half we can see from Earth.

Think of it this way: Imagine a tennis ball under a single lamp. The lamp illuminates one hemisphere of the ball. Now walk around the ball:

- When you’re on the same side as the lamp, you see mostly the dark side (new moon equivalent)

- When you’re opposite the lamp, you see the fully lit side (full moon equivalent)

- At intermediate angles, you see a crescent, quarter, or gibbous view

During a full moon, the portion of the Moon that is illuminated by the Sun is:

- 100% (the entire Moon)

- 50% (half the Moon)

- More than 50% because the Sun is very bright

- It varies depending on the season

B) 50% (half the Moon). The Sun ALWAYS illuminates exactly half of any sphere. During a full moon, we see essentially all of that lit half because the Moon is opposite the Sun from our perspective. The amount of the Moon that’s lit by the Sun (50%) never changes — only how much of that lit half we can see from Earth changes.

Draw the Sun on the left side of your page (or just an arrow showing sunlight direction). Draw Earth in the center. Now draw the Moon in four positions: 1. Between Earth and Sun (New Moon) 2. To the right of Earth (First Quarter) 3. Opposite the Sun from Earth (Full Moon) 4. To the left of Earth (Third Quarter)

For each Moon position, shade the half facing away from the Sun. Then ask: from Earth’s perspective, how much of the lit half can I see?

🔭 Demo Exploration: Moon Phases

Open the Moon Phases Demo: astrobytes-edu.github.io/astr101-sp26/demos/moon-phases/

This interactive demo lets you connect the Moon’s position in its orbit to what it looks like from Earth. You can drag the Moon and watch the phase change in real-time.

What you’ll see in the demo: - Draggable Moon that you can move around Earth - Phase readout showing the current phase name - Illumination percentage showing how much of the Moon’s face is lit (from Earth’s perspective) - Days Since New Moon showing where you are in the lunar cycle - 🎯 Challenges for testing your understanding - Show Earth’s Shadow toggle to address the misconception

Demo Mission 1: Killing the Shadow Misconception

Predict before you explore: If phases were caused by Earth’s shadow, where would you expect to see the shadow for a first quarter moon?

Write your prediction here before continuing: _______________

Do this: 1. Turn on Show Earth’s Shadow 2. Drag the Moon to create a First Quarter phase 3. Observe where Earth’s shadow is located

Key question: Is Earth’s shadow anywhere near the Moon during first quarter?

Earth’s shadow is nowhere near the Moon during first quarter (or crescent, or gibbous phases). The shadow points directly away from the Sun — and during first quarter, the Moon is 90° away from that shadow line.

Claim: Phases have nothing to do with Earth’s shadow.

Evidence: The demo’s shadow overlay shows Earth’s shadow pointing in the anti-solar direction, while the Moon at first quarter is 90° away from that line. The shadow and Moon don’t even come close during normal phases.

The shadow only matters during the rare alignment of a lunar eclipse.

Demo Mission 2: Position → Appearance

Do this: 1. Drag the Moon to the position directly between Earth and Sun 2. Note the Phase reading 3. Drag the Moon to the position directly opposite the Sun from Earth 4. Note the Phase reading 5. Drag to intermediate positions and observe how phase changes smoothly

| Moon Position | Phase |

|---|---|

| Between Earth and Sun | |

| Opposite Sun from Earth | |

| 90° east of Sun | |

| 90° west of Sun |

The pattern: How does the Moon’s position in its orbit determine what we see?

- Between Earth and Sun (conjunction): We see the Moon’s unlit side → New Moon

- Opposite Sun from Earth (opposition): We see the Moon’s fully lit side → Full Moon

- 90° east of Sun: Half lit, growing → First Quarter

- 90° west of Sun: Half lit, shrinking → Third Quarter

Claim: The Moon’s position in its orbit completely determines its phase.

Evidence: As you drag the Moon in the demo, the Phase readout changes predictably with position. The angular separation from the Sun (as seen from Earth) directly controls what phase we see — no other factors needed.

Conjunction: Two objects appear in the same direction on the sky; here, the Moon is (nearly) in the same direction as the Sun.

Opposition: Two objects appear 180° apart on the sky; here, the Moon is opposite the Sun.

Demo Mission 3: Challenge Mode

Do this: 1. Open the 🎯 Challenges panel 2. Try to create each of these phases: - New Moon - First Quarter - Full Moon - Third Quarter

For each challenge, position the Moon correctly, then check your answer.

Why this matters: If you can create a phase by positioning the Moon, you understand the geometry. You’re not memorizing — you’re reasoning.

- New Moon: Moon between Earth and Sun (sunward side)

- First Quarter: Moon 90° east of Sun (right side if Sun is up)

- Full Moon: Moon opposite from Sun (anti-sunward side)

- Third Quarter: Moon 90° west of Sun (left side if Sun is down)

The “quarter” in quarter moon refers to the orbital position (¼ of the way around), not the illumination (which is half).

To go from new moon to full moon, the Moon must:

- Move closer to Earth

- Move about 180° around its orbit

- Enter Earth’s shadow

- Wait for the Sun to move

B) Move about 180° around its orbit. At new moon, the Moon is on the sunward side of Earth. At full moon, it’s on the anti-sunward side — exactly opposite. That’s a 180° journey around the orbit. Since the full lunar cycle takes about 29.5 days, this journey from new to full takes about 14.75 days (approximately two weeks).

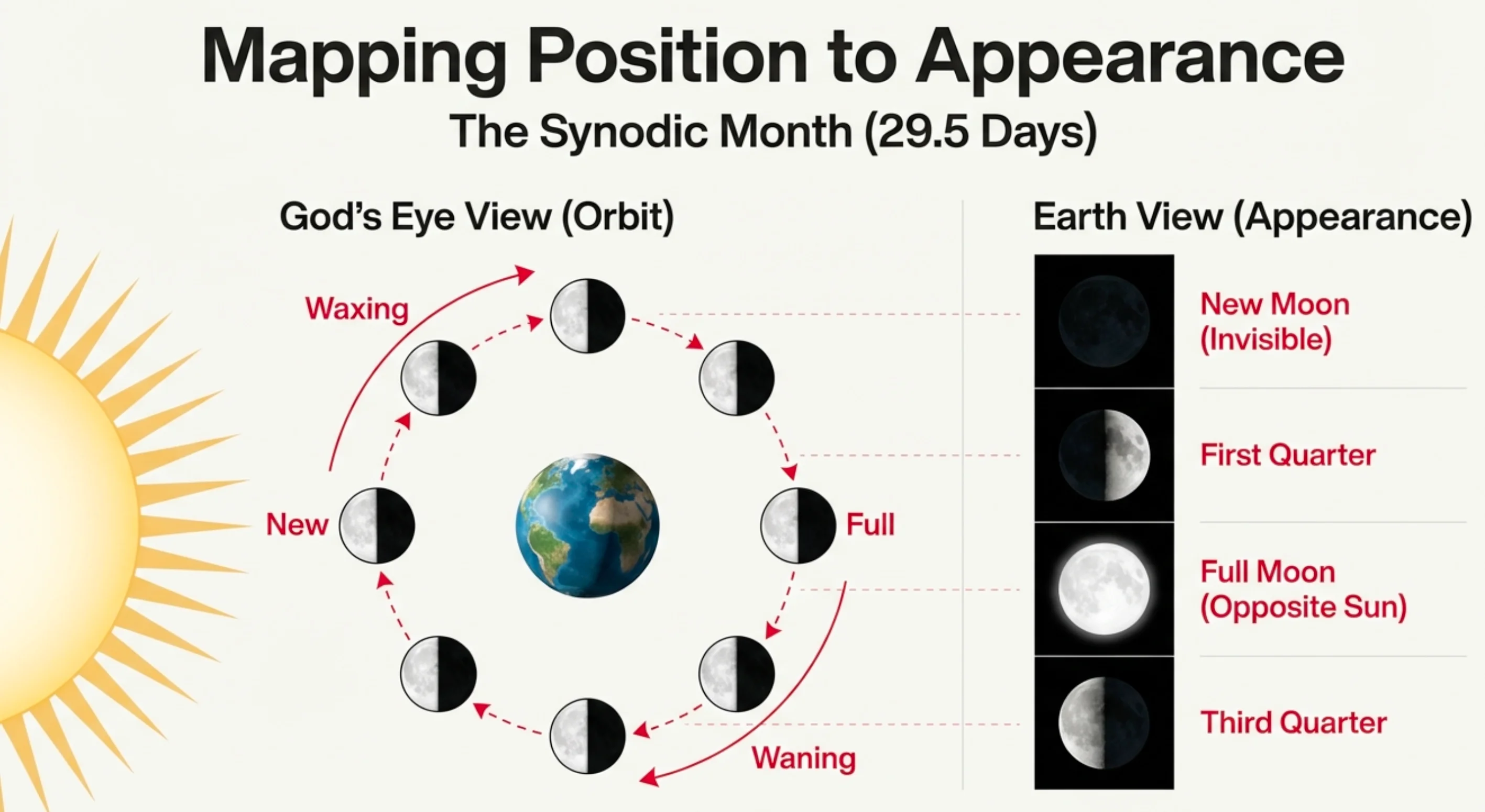

The Eight Phases

The lunar cycle is traditionally divided into eight named phases:

Note on “illumination”: In the table below, the percentage refers to how much of the Moon’s Earth-facing disk looks lit, not how much of the Moon the Sun is lighting (which is always 50%).

Phase vocabulary (decode the name):

- Waxing = getting brighter (new → full)

- Waning = getting dimmer (full → new)

- Crescent = less than half of the visible disk looks lit

- Gibbous = more than half (but not full) looks lit

- Quarter = about half looks lit (the “quarter” refers to the Moon being about ¼ or ¾ of the way around its orbit)

| Phase | Visible Disk Illuminated (%) | Position | Moon Rising | Moon Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| New Moon | ~0% | Between Earth & Sun | ~Sunrise | ~Sunset |

| Waxing Crescent | 1-49% | Moving toward first quarter | Morning | Evening |

| First Quarter | ~50% (right half*) | 90° from Sun, ~1 week after new | ~Noon | ~Midnight |

| Waxing Gibbous | 51-99% | Moving toward full | Afternoon | After midnight |

| Full Moon | ~100% of visible disk | Opposite the Sun | ~Sunset | ~Sunrise |

| Waning Gibbous | 99-51% | Moving toward third quarter | Evening | Morning |

| Third Quarter | ~50% (left half*) | 90° from Sun, ~1 week after full | ~Midnight | ~Noon |

| Waning Crescent | 49-1% | Moving toward new | After midnight | Afternoon |

(*As seen from the Northern Hemisphere; reversed in the Southern Hemisphere.)

The moon phase cycle around Earth (Credit: Cococubed)

Synodic month: why the phase cycle is not the same as the Moon’s orbital period (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Waxing: Growing in illumination (new → full). From Old English weaxan, “to grow.”

Waning: Shrinking in illumination (full → new). From Old English wanian, “to lessen.”

Gibbous: More than half but less than fully illuminated. From Latin gibbosus, “humpbacked.”

A “waxing gibbous” moon is:

- Less than half illuminated and getting brighter

- More than half illuminated and getting brighter

- More than half illuminated and getting dimmer

- Exactly half illuminated

B) More than half illuminated and getting brighter. “Waxing” means increasing illumination (heading toward full moon). “Gibbous” means more than half lit (between quarter and full). So waxing gibbous is after first quarter, before full moon — more than 50% illuminated and growing.

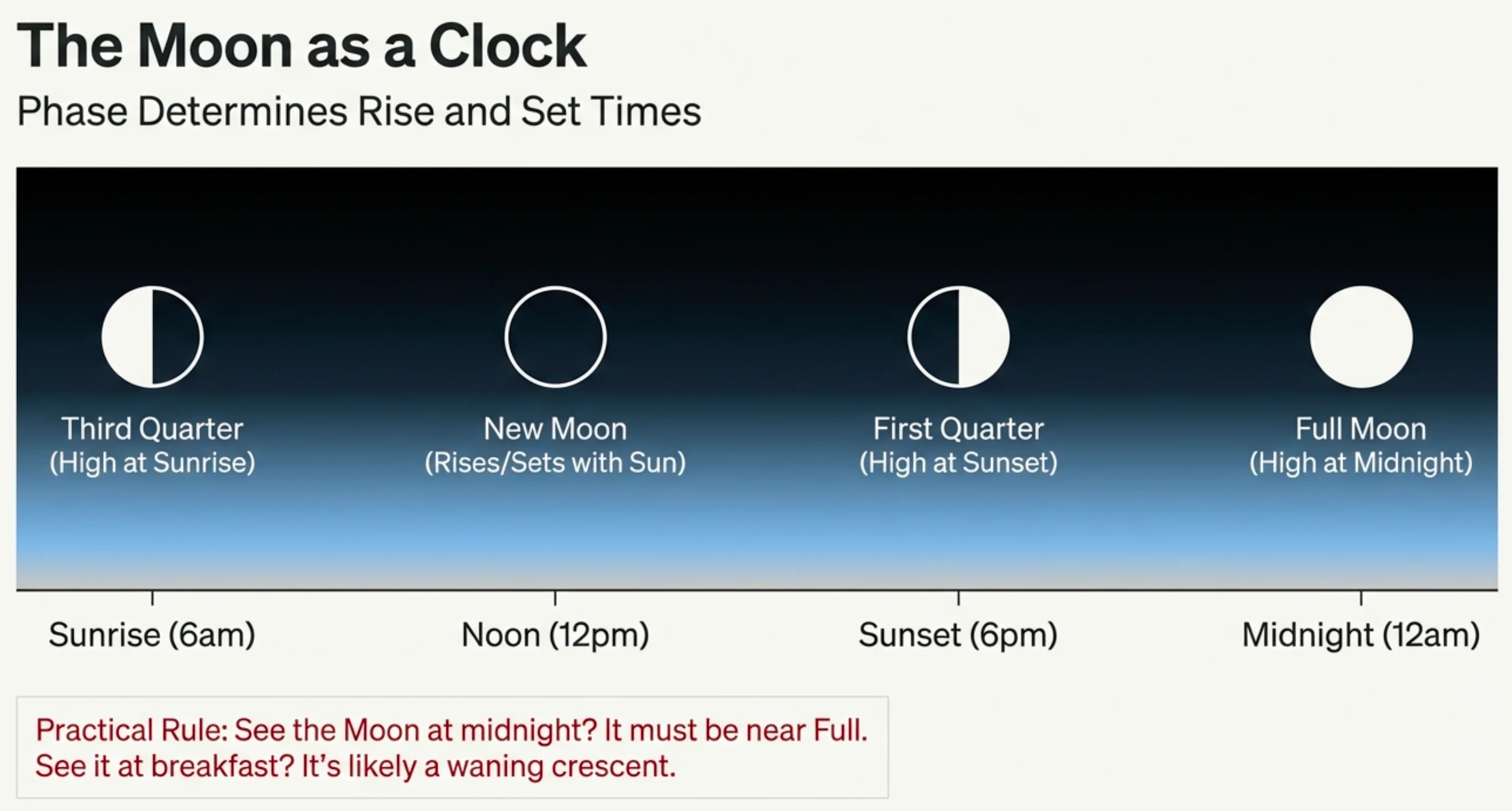

When Is the Moon Up?

Understanding phases gives you a superpower: predicting when the Moon is visible.

The Moon’s position relative to the Sun determines not just its appearance, but when it rises and sets:

New Moon: Near the Sun → rises with the Sun, sets with the Sun, lost in daytime glare

First Quarter: About a week after new → rises around noon, highest at sunset, sets around midnight

Full Moon: Opposite the Sun → rises at sunset, highest at midnight, sets at sunrise (visible all night!)

Third Quarter: About a week after full → rises around midnight, highest at sunrise, sets around noon

Using the Moon’s phase as a rough clock (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Practical application: If you see the Moon high in the sky at 3 AM, what phase must it be? It has to be past full (waning gibbous or third quarter), because only those phases are high in the sky in the pre-dawn hours.

You see a crescent Moon low in the western sky just after sunset. Is this moon waxing or waning?

- Waxing (getting brighter over coming days)

- Waning (getting dimmer over coming days)

- Could be either

- Crescent moons are never visible at sunset

A) Waxing (getting brighter over coming days). A crescent Moon visible in the evening (after sunset, in the west) is a waxing crescent — moving from new toward first quarter. A waning crescent would be visible in the pre-dawn eastern sky, not the evening western sky. Position and time together tell you the phase trajectory.

It’s midnight, and the Moon is highest in the sky. What phase is it?

- New Moon

- First Quarter

- Full Moon

- Third Quarter

C) Full Moon. The full moon is opposite the Sun. At midnight, the Sun is on the opposite side of Earth (below your feet, roughly). The Moon being highest in the sky at midnight means it’s in the anti-sunward direction — which is the full moon position. (First quarter is highest in the early evening; third quarter is highest in the early morning.)

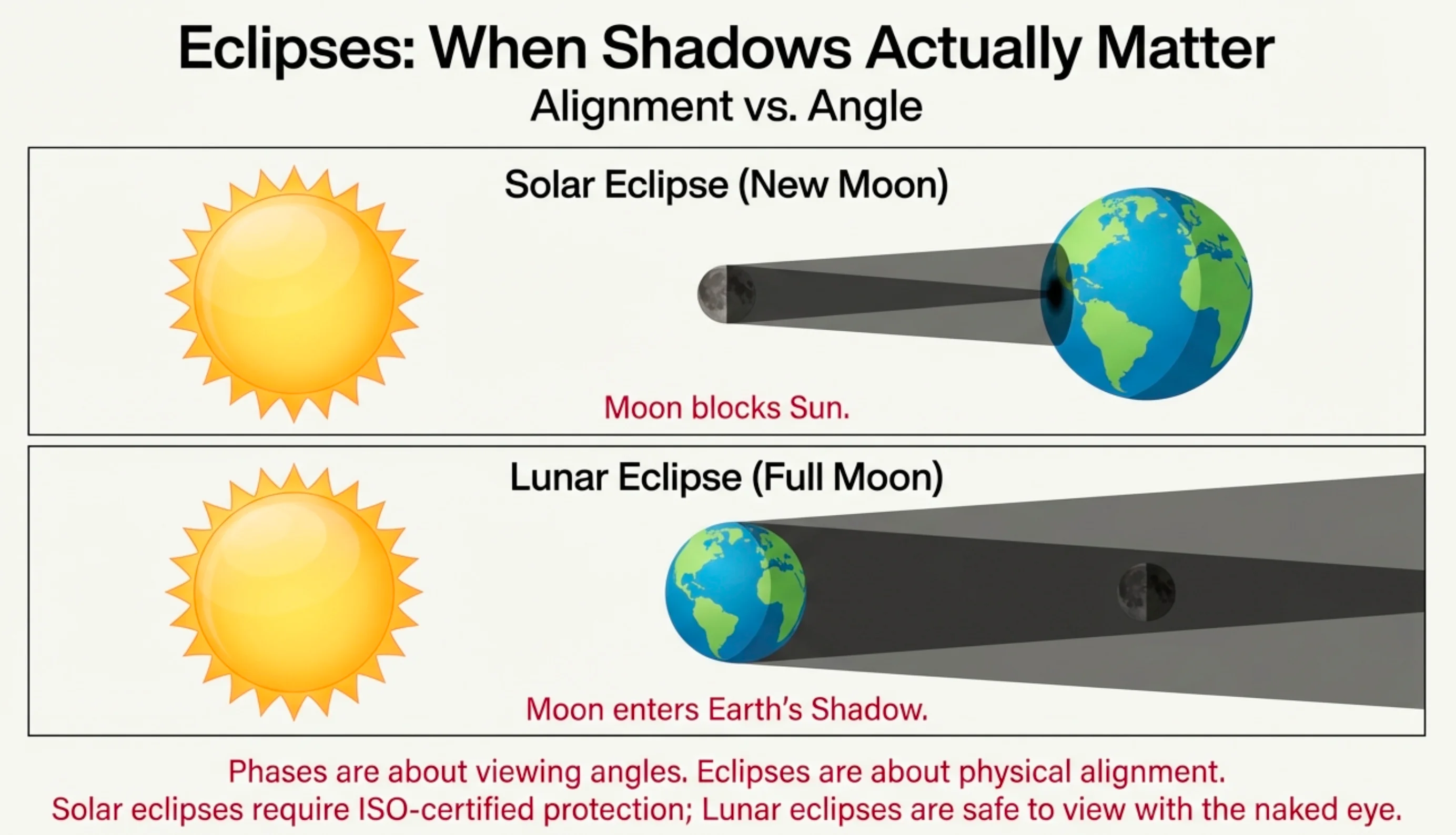

Eclipses: When Shadows Actually Matter

What Are Eclipses?

Now we finally talk about shadows.

An eclipse occurs when one celestial body passes through the shadow of another:

- Solar eclipse: Moon’s shadow falls on Earth (Moon between Sun and Earth)

- Lunar eclipse: Moon passes through Earth’s shadow (Earth between Sun and Moon)

What to notice: Eclipses are about shadows (umbra/penumbra) and alignment; phases are not. (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Varieties of eclipses from alignment geometry (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

For an eclipse to happen, you need a very specific alignment: Sun, Earth, and Moon must be nearly collinear (in a straight line).

During a solar eclipse, the Moon is at what phase?

- Full Moon

- New Moon

- First Quarter

- Third Quarter

B) New Moon. For the Moon’s shadow to reach Earth, the Moon must be between Earth and the Sun — which is the new moon position. Solar eclipses can only occur at new moon. (Lunar eclipses can only occur at full moon, when the Moon is opposite the Sun and can pass through Earth’s shadow.)

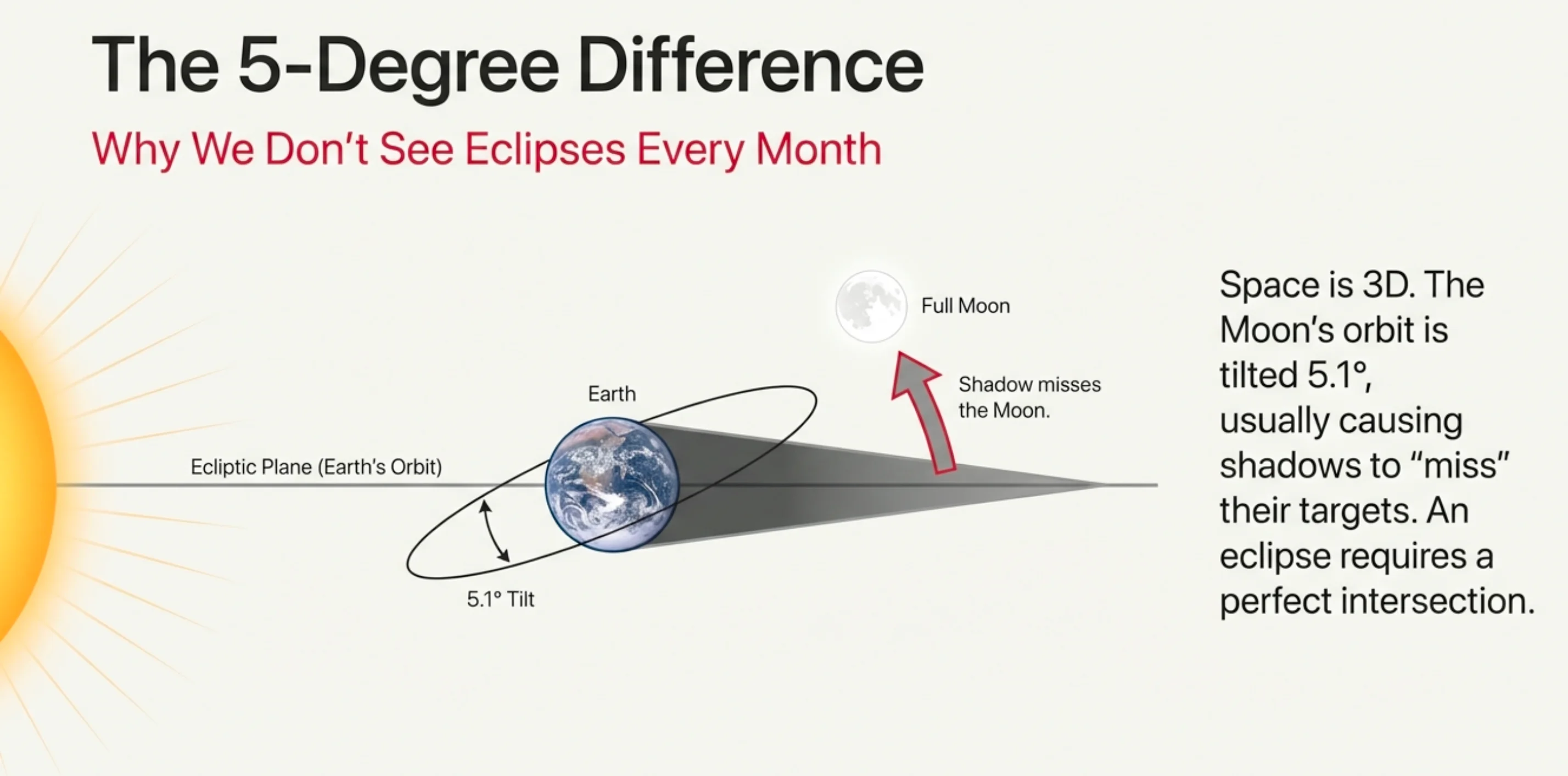

Why Not Every Month?

Here’s the puzzle: If solar eclipses happen at new moon, and lunar eclipses happen at full moon, why don’t we get two eclipses every month?

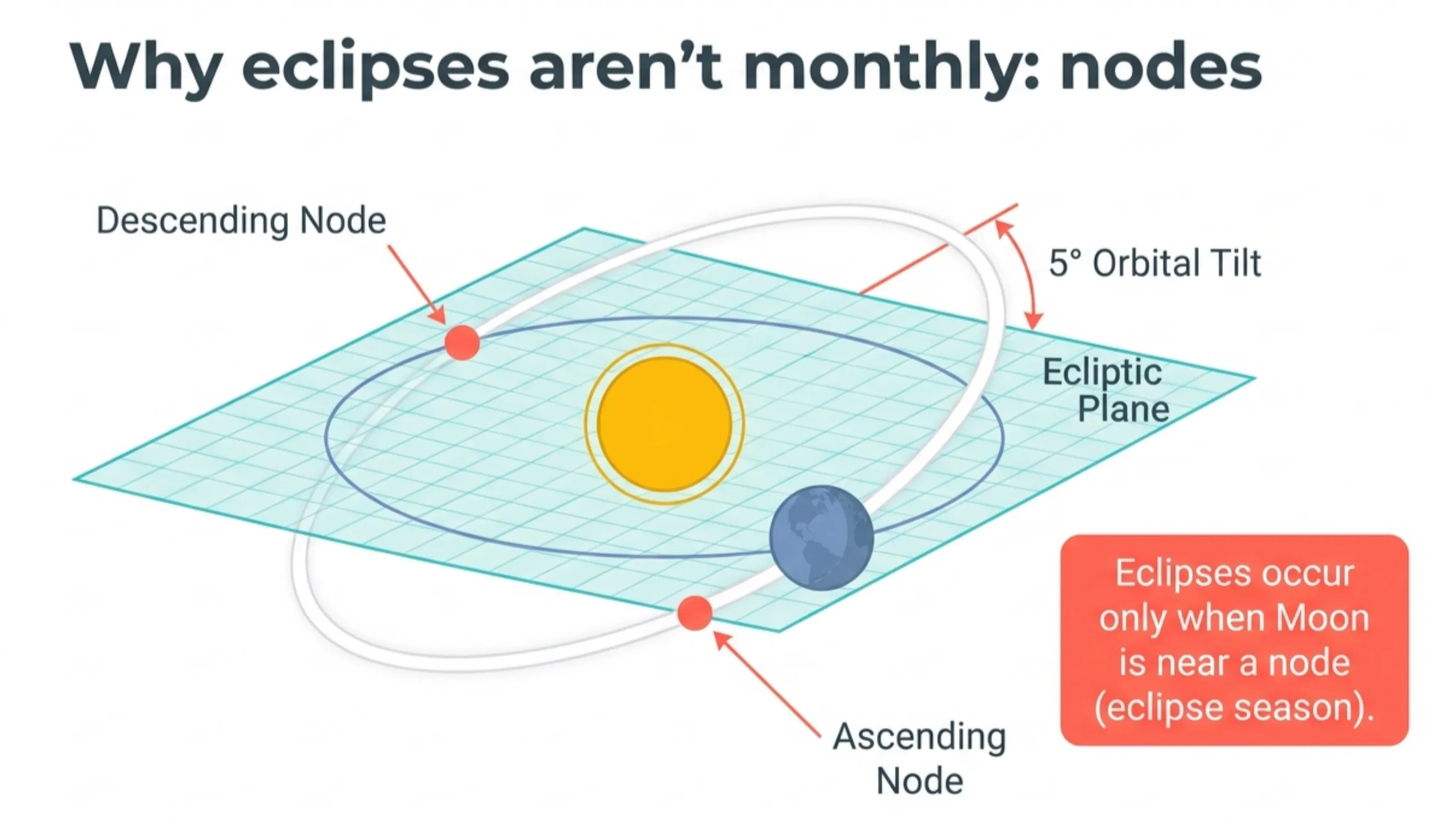

The answer is the tilt of the Moon’s orbit.

The Moon’s orbit around Earth is tilted about 5.1° relative to the ecliptic (the plane of Earth’s orbit around the Sun). This might sound small, but it’s enough to change everything.

Because of this tilt, at most new moons, the Moon passes above or below the Sun as seen from Earth — no solar eclipse. At most full moons, the Moon passes above or below Earth’s shadow — no lunar eclipse.

Why eclipses don’t happen every month: the Moon’s orbit is tilted (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Orbital nodes: the alignment gateways for eclipses (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Draw a horizontal line across your page — this is the ecliptic plane (Earth’s orbital plane around the Sun).

Now draw the Moon’s orbit as a tilted ellipse, crossing the ecliptic at two points. Label these crossing points as nodes.

Place the Moon at four positions: (1) at a node during new moon, (2) away from a node during new moon, (3) at a node during full moon, (4) away from a node during full moon.

For which positions is an eclipse possible? This sketch explains why eclipses don’t happen every month!

Eclipses don’t occur every month because:

- The Moon is too small to cast a significant shadow

- The Moon’s orbit is tilted relative to Earth’s orbital plane

- Earth’s atmosphere bends the Moon’s shadow away

- The Sun is too bright during most new moons

B) The Moon’s orbit is tilted relative to Earth’s orbital plane. The ~5° tilt means the Moon usually passes above or below the direct line between Sun and Earth (at new moon) or above/below Earth’s shadow (at full moon). Only when the alignment is nearly perfect — which requires the Moon to be near a node — can eclipses occur.

🔭 Demo Exploration: Eclipse Geometry

Open the Eclipse Geometry Demo: astrobytes-edu.github.io/astr101-sp26/demos/eclipse-geometry/

This interactive demo lets you see why eclipses don’t happen every month — and when they do.

What you’ll see in the demo: - NO ECLIPSE / SOLAR ECLIPSE / LUNAR ECLIPSE status indicator - “Moon is X° above/below ecliptic plane” readout - Orbital Tilt slider (normally 5.1°) - Current Phase indicator - Node markers showing where the Moon’s orbit crosses the ecliptic - Long-Term Simulation controls

Demo Mission 1: Break the Universe (Tilt = 0°)

Predict before you explore: If the Moon’s orbital tilt were zero, how often would eclipses occur?

Write your prediction here before continuing: _______________

Do this: 1. Set Orbital Tilt to 0° (eclipse every month!) 2. Drag the Moon to the new moon position 3. Check the eclipse status 4. Drag to the full moon position 5. Check the eclipse status again

What happens when there’s no tilt?

With 0° tilt, you get an eclipse every time: - New moon → SOLAR ECLIPSE (every time!) - Full moon → LUNAR ECLIPSE (every time!)

Claim: Orbital tilt is the ONLY reason eclipses aren’t monthly events.

Evidence: Setting the demo’s Orbital Tilt to 0° produces eclipses at every new moon and every full moon. The status indicator confirms “SOLAR ECLIPSE” and “LUNAR ECLIPSE” at those phases. The 5.1° tilt is what breaks the monthly alignment.

Demo Mission 2: Restore Reality (Tilt = 5.1°)

Do this: 1. Set Orbital Tilt back to 5.1° 2. Drag the Moon slowly around its orbit 3. Watch the “Moon is X° above/below ecliptic plane” readout 4. Try to find positions where eclipses ARE possible

Key observations: - What does the readout say during most new moons? - Where are the only positions that allow eclipses?

With realistic tilt (5.1°): - At most orbital positions, the Moon is above or below the ecliptic plane by 1–5° - Eclipse status shows NO ECLIPSE even at new/full moon phases - Eclipses only become possible when the Moon is near a node — where its orbit crosses the ecliptic plane

Claim: Most new/full moons don’t produce eclipses because the Moon is above or below the ecliptic plane.

Evidence: The demo’s readout shows “Moon is 3° above ecliptic plane” (or similar) during most new/full moons, and the status indicator shows “NO ECLIPSE.” Only near the nodes does the readout approach 0° and eclipses become possible.

Demo Mission 3: Finding the Nodes

Do this: 1. Look for the Node markers in the orbit view 2. Position the Moon at a node during new moon phase 3. Check if a solar eclipse is possible 4. Position the Moon at a node during full moon phase 5. Check if a lunar eclipse is possible

Key question: What do the nodes represent physically?

The nodes are the two points where the Moon’s tilted orbit crosses the ecliptic plane: - Ascending node: Moon crosses from below to above the ecliptic - Descending node: Moon crosses from above to below the ecliptic

Only when the Moon is near a node AND at the right phase (new or full) can an eclipse occur. The rest of the month, the Moon is too far above or below the ecliptic plane for the shadows to connect.

Demo Mission 4: Long-Term Eclipse Statistics

Do this: 1. Find the Long-Term Simulation controls 2. Set Simulate Years = 10 and click Run Simulation 3. Count total solar eclipses and lunar eclipses 4. Repeat for Simulate Years = 100

| Time Period | Solar Eclipses | Lunar Eclipses |

|---|---|---|

| 10 years | ||

| 100 years |

What pattern emerges?

Over long periods, you should see: - About 2–5 solar eclipses per year (average ~2.4) - Lunar eclipses also occur a few times per year globally (some are subtle penumbral eclipses; if you count only the darker umbral lunar eclipses, there can be 0–3 per year)

This is far fewer than the 12–13 new moons and 12–13 full moons per year! The geometric restrictions imposed by orbital tilt make eclipses relatively rare events.

Note: Solar eclipses are visible from a MUCH smaller area (narrow path) than lunar eclipses (entire night-side of Earth), so experiencing a solar eclipse is rarer than experiencing a lunar eclipse.

Based on the Eclipse Geometry demo, approximately how many total solar eclipses occur per year (on average)?

- 0-1

- 2-5

- 12-13 (one per month)

- 24-26 (two per month)

B) 2-5. There are about 2-5 solar eclipses per year globally. The exact number varies because the eclipse seasons don’t always contain both new moons needed for eclipses, and sometimes eclipse seasons overlap calendar years differently. The key insight is that it’s FAR fewer than monthly.

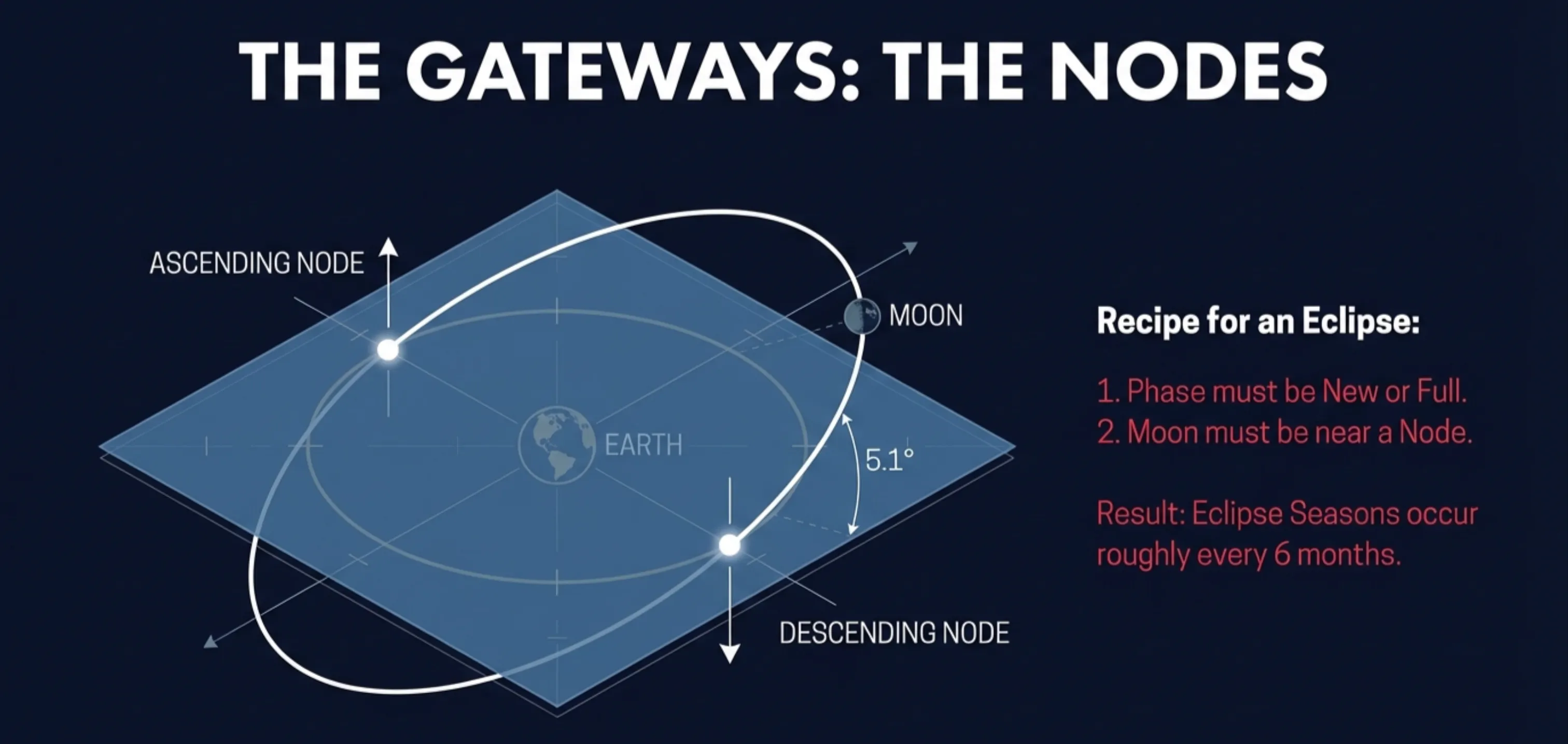

The Nodes: Eclipse Gateways

The nodes are the two points where the Moon’s orbit crosses the ecliptic plane:

Node: A point where the Moon’s orbital plane intersects the ecliptic plane. The ascending node is where the Moon crosses northward; the descending node is where it crosses southward.

Nodes as eclipse “gateways” along the Moon’s orbit (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

The nodes aren’t fixed — they slowly drift (regress) around the ecliptic with a period of about 18.6 years (the lunar nodal cycle). This means the eclipse seasons slowly shift through the calendar year.

The Saros cycle (~18 years, 11 days, 8 hours) is a different kind of eclipse repetition. After one Saros, the Sun–Earth–Moon geometry repeats closely enough that a similar eclipse occurs again (though usually shifted in location by about 120° in longitude due to the extra 8 hours). The Saros results from multiple lunar month-periods lining up, not from nodal precession alone.

Ancient astronomers discovered the Saros empirically and used it to predict eclipses centuries in advance!

Eclipse Seasons

Because there are two nodes on opposite sides of the Moon’s orbit, eclipses tend to occur in pairs roughly 6 months apart. These periods are called eclipse seasons.

During an eclipse season: - If a new moon occurs while the Sun is near a node → solar eclipse possible - If a full moon occurs while the Sun is near a node → lunar eclipse possible

Each eclipse season lasts about 34–35 days (≈34.5 days on average) — long enough that at least one new moon or full moon typically occurs within it. Eclipse seasons occur about twice per year, roughly 6 months apart, and each season can produce up to three eclipses (solar, lunar, solar) if the timing is right.

If a solar eclipse occurs on March 15, when might the next lunar eclipse occur?

- The very next full moon (about 2 weeks later)

- Exactly 6 months later

- The next full moon AND the full moon 6 months later are both possibilities

- Lunar eclipses can only occur in years without solar eclipses

C) The next full moon AND the full moon 6 months later are both possibilities. If a solar eclipse occurred (Sun was near a node at new moon), then the same eclipse season could produce a lunar eclipse about 2 weeks later at the following full moon — the Sun will still be near the node. Additionally, about 6 months later, the Sun will be near the other node, creating another eclipse season with lunar eclipse potential.

Types of Eclipses

Solar Eclipse Types

Never look at the Sun during partial or annular phases without proper solar filters or eclipse glasses (ISO 12312-2 certified). Regular sunglasses are NOT safe. Never look at the Sun through binoculars or a telescope without a proper front-mounted solar filter, even if you’re wearing eclipse glasses. During the brief totality phase of a total eclipse (and ONLY during totality), it is safe to view with the naked eye — but you must use protection before and after.

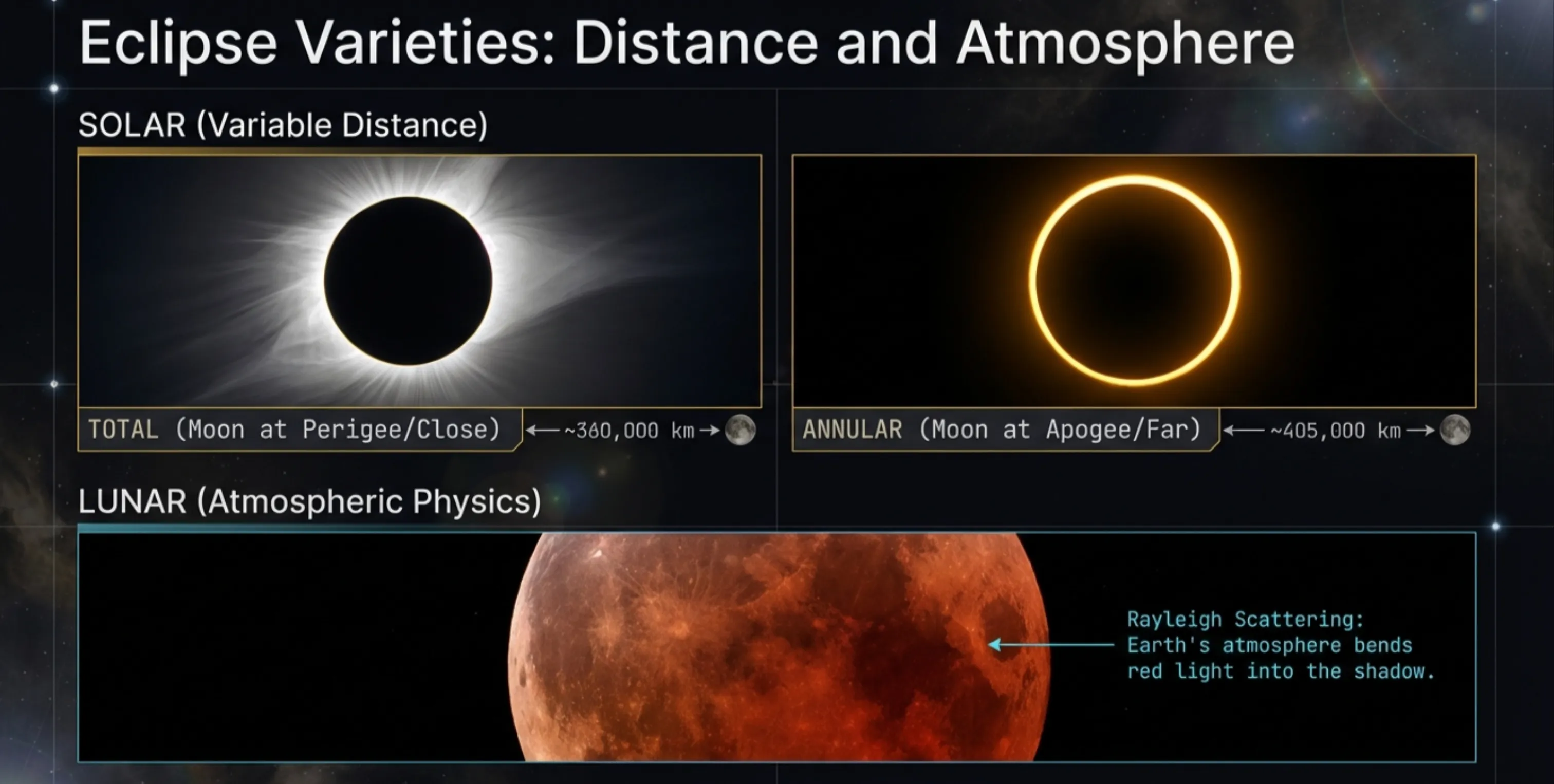

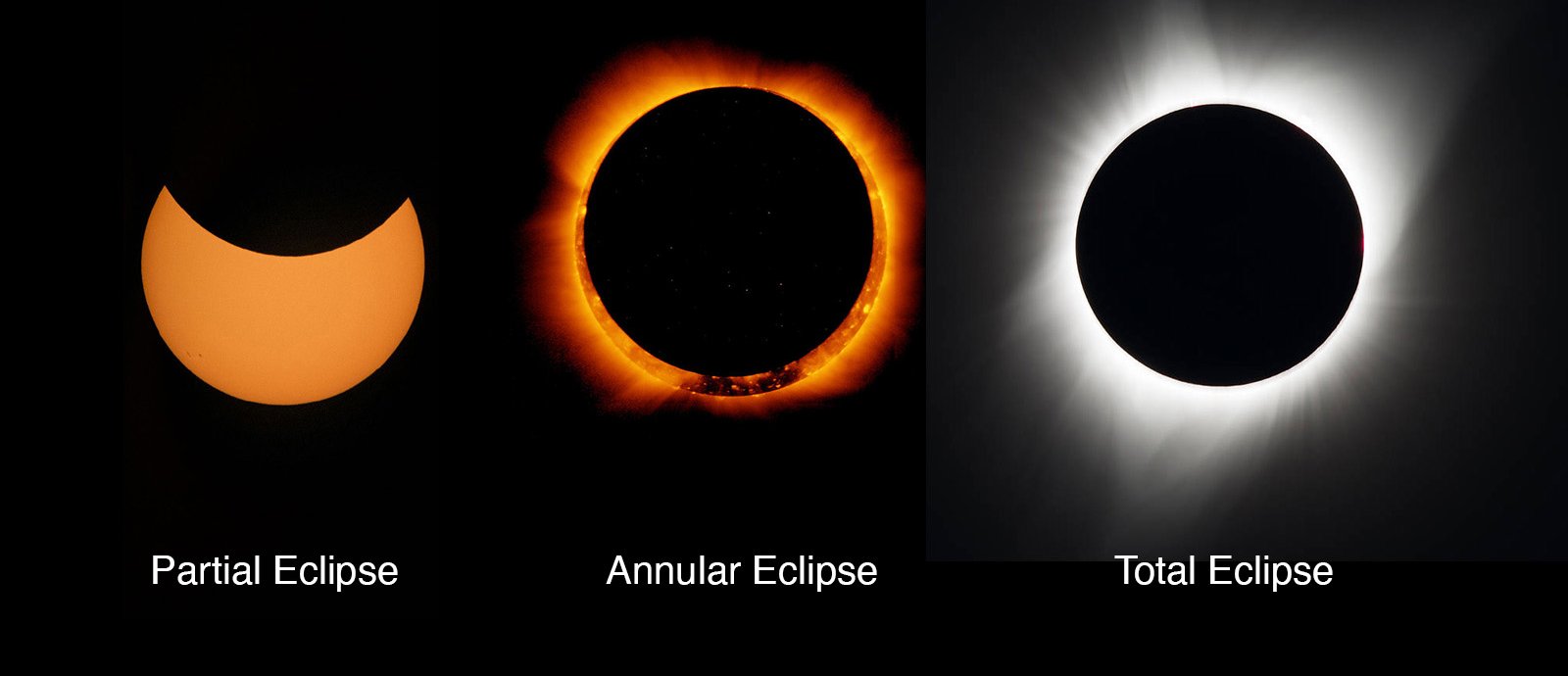

Not all solar eclipses are created equal. The type depends on the geometry:

| Type | Description | What You See |

|---|---|---|

| Total | Moon completely covers the Sun | Corona visible, darkness at midday |

| Annular | Moon is centered on Sun but appears smaller | “Ring of fire” around Moon |

| Partial | Moon only partially covers the Sun | Sun looks “bitten” |

| Hybrid | Transitions between total and annular along the path | Rare; both total and annular visible depending on location |

Solar eclipse types: partial, annular, and total (Credit: Source: [VERIFY])

Why the variation?

- Total vs. Annular: Depends on the Moon’s angular size relative to the Sun. When the Moon appears larger than the Sun (Moon closer to Earth), we get a total eclipse. When it appears smaller (Moon farther from Earth), we get an annular eclipse.

- Partial: The observer is in the penumbra (partial shadow), not the umbra (full shadow).

Eclipse vocabulary (quick map):

- Umbra = full shadow (light source completely blocked)

- Penumbra = partial shadow (light source partly blocked)

- Total solar eclipse: you are in the Moon’s umbra (Sun fully covered)

- Partial solar eclipse: you are in the Moon’s penumbra (Sun partly covered)

- Annular solar eclipse: Moon is centered on Sun but appears smaller, so a bright ring remains

During an annular solar eclipse, the Moon:

- Is closer to Earth than during a total eclipse

- Is farther from Earth than during a total eclipse

- Has a larger angular size than the Sun

- Passes through Earth’s shadow

B) Is farther from Earth than during a total eclipse. When the Moon is at a more distant point in its elliptical orbit (near apogee), its angular size is smaller than the Sun’s angular size. Even when perfectly aligned, the smaller-appearing Moon can’t completely cover the Sun — leaving a ring (annulus) of sunlight visible. This is an annular eclipse.

Lunar Eclipse Types

Lunar eclipses also come in varieties:

| Type | Description | What You See |

|---|---|---|

| Total | Moon fully enters Earth’s umbra | Reddish “blood moon” |

| Partial | Moon only partially enters umbra | Part of Moon darkened |

| Penumbral | Moon only passes through penumbra | Subtle shading (often hard to notice) |

Total lunar eclipse (“blood moon”) from Earth’s atmospheric filtering (Credit: (A. Rosen/NotebookLM))

Draw the Sun on the left (large circle). Draw Earth in the middle (small circle). Now draw Earth’s shadow extending to the right: - The umbra is the dark inner cone where the Sun is completely blocked - The penumbra is the lighter outer region where only part of the Sun is blocked

Now draw the Moon passing through different parts of this shadow. Where must it be for a total lunar eclipse? A partial? A penumbral?

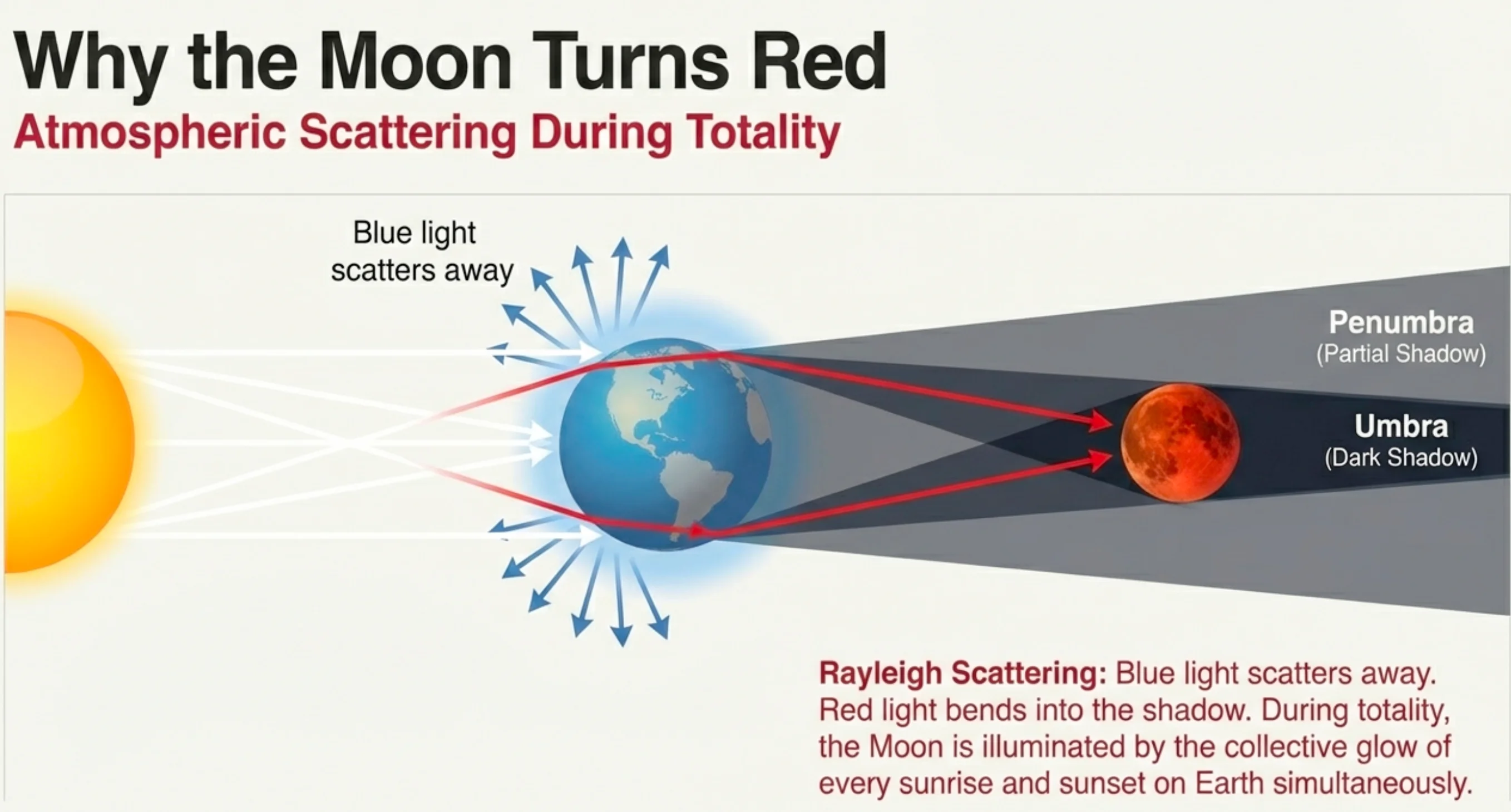

Why does the Moon turn red during a total lunar eclipse?

Earth’s atmosphere bends (refracts) and filters sunlight. Blue light scatters away (the same reason our sky is blue), but red light bends around Earth’s edge and reaches the Moon. The Moon is literally being illuminated by all the sunrises and sunsets happening on Earth simultaneously!

The Moon turns reddish during a total lunar eclipse because:

- The Moon reflects light from Mars

- Earth’s atmosphere filters out blue light, allowing red to reach the Moon

- The Moon’s surface changes color when cold

- Earth’s shadow is inherently red

B) Earth’s atmosphere filters out blue light, allowing red to reach the Moon. As sunlight passes through Earth’s atmosphere, blue wavelengths scatter (Rayleigh scattering — same reason our sky is blue). Red wavelengths pass through more easily and get bent around Earth’s edge into the shadow zone. This red light illuminates the Moon, creating the “blood moon” appearance.

Why Total Solar Eclipses Are Special

Lunar eclipses are visible from anywhere on Earth’s night side — potentially billions of people can see each one.

Total solar eclipses? The path of totality (where the Moon fully covers the Sun) is typically only about 100-250 km wide and traces a narrow path across Earth’s surface. Outside this path, observers see only a partial eclipse.

The numbers: - Total eclipse path width: ~100-250 km - Total eclipse path length: ~10,000-15,000 km - Duration of totality at any location: typically 2-7 minutes - Any given location experiences a total solar eclipse roughly once every 375 years on average

This is why eclipse chasers travel around the world — you often have to go to the eclipse, because the eclipse probably won’t come to you in your lifetime.

Angular Size Revisited: Total vs. Annular

Remember from Lecture 3: the Sun and Moon have nearly the same angular size (~0.5°). This is the key to understanding total vs. annular solar eclipses.

The Moon’s distance varies: - At perigee (closest): ~356,500 km → angular size ~0.56° - At apogee (farthest): ~406,700 km → angular size ~0.49°

The Sun’s angular size also varies slightly: - At perihelion (Earth closest to Sun): ~0.54° - At aphelion (Earth farthest from Sun): ~0.52°

When the Moon’s angular size exceeds the Sun’s, total eclipses are possible.

When the Moon’s angular size is smaller than the Sun’s, only annular eclipses can occur. At perigee, the Moon appears slightly larger than the Sun (total eclipse possible); at apogee, it appears smaller (only annular possible).

If the Moon were 20% farther from Earth than it is now, solar eclipses would be:

- More frequent

- Always total

- Always annular (never total)

- Exactly the same

C) Always annular (never total). If the Moon were 20% farther away, its angular size would be about 20% smaller — roughly 0.4° instead of 0.5°. Since the Sun’s angular size is about 0.5°, the Moon would never appear large enough to completely cover the Sun. Every solar eclipse would be annular, with a ring of sunlight visible.

The Moon Is Leaving

Here’s an extraordinary fact: total solar eclipses are a temporary gift from the cosmos.

The Moon is receding from Earth at about 3.8 cm per year. We measure this directly by bouncing laser beams off retroreflectors left on the Moon by Apollo astronauts (and Soviet Lunokhod rovers). Lunar laser ranging measures the Moon’s distance to centimeter precision, confirming the Moon is slowly drifting away.

What this means: - In the distant past, the Moon was much closer and appeared much larger in the sky - Total solar eclipses lasted longer - Eventually (in ~600 million years), the Moon will be too far away to ever fully cover the Sun - After that, only annular and partial eclipses will be possible

The Moon rotates once per orbit, which is why we always see the same face — this is called tidal locking. The same tidal physics that locked the Moon’s rotation is also pushing the Moon slowly outward over time. We’ll explore how this works when we cover gravity and tides later in the course.

We live in a privileged epoch — a cosmic window when total solar eclipses are possible but not too long. A billion years ago, the Moon would have appeared huge. A billion years from now, it will be too small for totality.

Lunar laser ranging experiments show that the Moon is:

- Moving toward Earth at 3.8 cm/year

- Moving away from Earth at 3.8 cm/year

- Staying at a constant distance

- Oscillating in and out

B) Moving away from Earth at 3.8 cm/year. This recession is caused by tidal interactions — the same forces that create ocean tides slowly transfer angular momentum from Earth’s rotation to the Moon’s orbit. As the Moon gains orbital energy, it spirals outward. The measurement is precise thanks to retroreflectors placed on the Moon during Apollo missions.

Connecting the Concepts

Let’s synthesize everything from today:

Moon phases result from geometry, not shadows. The Sun always illuminates half the Moon; what changes is how much of that lit half we can see from Earth. Position in orbit → angle of view → phase appearance.

Eclipses happen when shadows actually align. Solar eclipses require the Moon to be directly between Sun and Earth (new moon); lunar eclipses require Earth to be directly between Sun and Moon (full moon).

Why not monthly? The Moon’s orbit is tilted 5.1° from the ecliptic. This tilt causes most new moons to pass above or below the Sun, and most full moons to miss Earth’s shadow. Only near the nodes — where the Moon’s orbit crosses the ecliptic — can eclipses occur.

Total vs. annular depends on angular size. The Moon’s elliptical orbit means its angular size varies. When the Moon appears larger than the Sun, totality is possible. When it appears smaller, we get an annular eclipse.

We are lucky to witness total solar eclipses at all. The Moon is slowly receding, and in geological time, total eclipses will become impossible.

Coming Friday: Our Week 2 Activity will bring together all four interactive demos (Seasons, Angular Size, Moon Phases, Eclipse Geometry) in an integrated exploration. You’ll use everything you’ve learned to solve geometry puzzles about the Earth-Moon-Sun system.

Practice Problems

Conceptual Questions

1. Phase vs. Eclipse. In 2-3 sentences, explain the difference between what causes Moon phases and what causes lunar eclipses.

2. The Misconception. A friend tells you the crescent moon is caused by Earth’s shadow covering most of the Moon. Explain specifically why this cannot be correct.

3. Observing Challenge. You see a half-illuminated Moon high in the sky at 6 AM. Is this first quarter or third quarter? How do you know?

4. Eclipse Prediction. If you know a solar eclipse occurred on April 8, would you expect another eclipse possibility around October 8 of the same year? Explain why or why not.

5. Why Red? Explain why the Moon appears reddish during a total lunar eclipse, using what you know about Earth’s atmosphere.

Calculations

6. Synodic Month. The Moon takes 29.5 days to go from new moon to new moon (the synodic period). If new moon occurs on January 1, on approximately what date will the next full moon occur?

7. Angular Size Comparison. The Moon’s average angular diameter is 0.52°. Jupiter’s largest moon, Ganymede, has an angular diameter of about 1.7 arcseconds when viewed from Earth. How many times larger does our Moon appear than Ganymede? (Hint: 1° = 3600 arcseconds)

8. Eclipse Frequency. If there are about 2.4 solar eclipses per year on average, and a given location on Earth experiences a total solar eclipse roughly once every 375 years, what does this tell you about what fraction of Earth’s surface the path of totality covers for a typical eclipse?

9. Lunar Recession. The Moon is receding at 3.8 cm/year.

- How far will the Moon have moved in 1000 years?

- The Moon’s current average distance is about 384,400 km. What percentage increase in distance does 1000 years of recession represent?

10. Day Length Connection. On the day of a first quarter moon, approximately how many hours pass between moonrise and moonset? Explain your reasoning based on the Moon’s position relative to the Sun.

Synthesis

11. Observable → Model → Inference. An ancient astronomer notices that the Moon’s angular size varies slightly from week to week. Following the Observable → Model → Inference pattern:

- What is being measured? (Which of the four observables?)

- What physical model could explain this observation?

- What could the astronomer infer about the Moon’s orbit?

12. Predicting Eclipses. The ancient Babylonians discovered that eclipses follow an 18-year, 11-day cycle (the Saros cycle). Using what you learned about nodes and eclipse seasons, explain why eclipses might repeat in such a regular pattern.

13. Demo Integration. Using both the Moon Phases and Eclipse Geometry demos, explain why you can have a new moon without a solar eclipse. What specific conditions must be met for a new moon to also produce a solar eclipse?

14. Future Eclipses (Modeling). The Moon is receding at ~3.8 cm/year.

- Estimate how much farther away the Moon would be in 600 million years if the rate stayed constant. Express your answer in kilometers.

- What percentage increase in distance does this represent? (Current average distance: 384,400 km)

- How would this affect the Moon’s angular size (percent change)?

- What would this mean for total solar eclipses?

Glossary

No glossary terms for lecture 4.